Chemistry

Chemistry (Federal High German: [çeˈmiː]; Austrian High German: [keˈmiː]) is that natural science which deals with the structure, properties and transformation of chemical substances. A substance consists of atoms, molecules, or both. It may also contain ions. The chemical reactions are processes in the electron shells of atoms, molecules and ions.

Central concepts of chemistry are chemical reactions and chemical bonds. Chemical bonds are formed or broken by chemical reactions. In the process, the electron residence probability in the electron shells of the substances involved changes and thus their properties. The production of substances (synthesis) with properties required by mankind is the central concern of chemistry today.

Traditionally, chemistry is divided into subfields. The most important of these are organic chemistry, which studies carbon-containing compounds, inorganic chemistry, which deals with all the elements of the periodic table and their compounds, and physical chemistry, which deals with the fundamental phenomena underlying chemistry.

Chemistry in its present form as an exact natural science gradually emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries from the application of rational reasoning based on observations and experiments of alchemy. Some of the first great chemists were Robert Boyle, Humphry Davy, Jöns Jakob Berzelius, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, Joseph Louis Proust, Marie and Antoine Lavoisier, and Justus von Liebig.

The chemical industry is one of the most important industrial sectors. It produces substances that are needed to manufacture everyday objects (e.g. basic chemicals, plastics, paints), foodstuffs (also as additives to these, such as fertilisers and pesticides) or to improve health (e.g. pharmaceuticals).

Thermite reaction

Test apparatus in the gas fume hood of a chemical laboratory

Word Origin

The term chemistry originated from ancient Greek χημεία chēmeía "[art of metal] foundry" in the sense of "transformation". The present spelling chemistry was probably first introduced by Johann Joachim Lange in 1750-1753, and in the early 19th century replaced the word chymie, which had existed since the 17th century and was probably a simplification and reinterpretation of the term alchemy, which had been documented since the 13th century. This word itself has an ambiguous etymology (for the connotations compare the etymology of the word alchemy): The word is probably rooted in Arabic al-kīmiyá, which can mean, among other things, "philosopher's stone", possibly from ancient Greek χυμεία chymeía "casting", or from Coptic/Egyptian kemi "black[e earth]", compare also Kemet).

Until the beginning of the 19th century, the terms "Scheidekunde" and "Scheidekunst" were considered alternatives for the word chemistry.

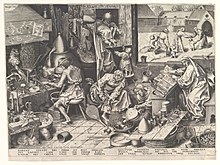

Engraving by Pieter Brueghel the Elder: The Alchemist

History

→ Main article: History of chemistry

Chemistry in antiquity consisted of the accumulated practical knowledge of substance transformation processes and the natural philosophical views of antiquity. Chemistry in the Middle Ages developed from alchemy, which had been practiced in China, Europe and India for thousands of years.

The alchemists were concerned both with the hoped-for refinement of metals (production of gold from base metals, see also transmutation) and with the search for medicines. For the production of gold in particular, the alchemists searched for an elixir (philosopher's stone, philosopher's stone) that would transform base ("sick") metals into noble ("healthy") metals. The medical branch of alchemy also sought an elixir, the elixir of life, a cure for all diseases, which would eventually confer immortality. However, no alchemist ever discovered the philosopher's stone or the elixir of life.

Until the end of the 16th century, the imagination of alchemists was usually not based on scientific research, but on facts of experience and empirical recipes. Alchemists conducted a wide range of experiments with many substances to achieve their goals. They noted their discoveries and used the same symbols for their records as were used in astrology. The mysterious nature of their activities and the colored flames, smoke, or explosions that often resulted led them to be known as magicians and sorcerers and sometimes persecuted. For their experiments, the alchemists developed some apparatuses that are still used today in chemical engineering.

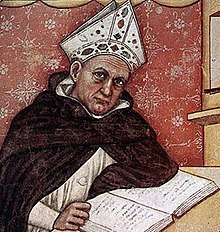

A well-known alchemist was Albertus Magnus. As a cleric, he dealt with this complex of topics and found a new chemical element, arsenic, in his experiments. It was not until the work of Paracelsus and Robert Boyle (The Sceptical Chymist, 1661) that alchemy changed from a purely Aristotelian science to a more empirical and experimental science, which became the basis of modern chemistry.

Chemistry in modern times received decisive impetus as a science in the 18th and 19th centuries: It was based on measurement processes and experiments, especially through the use of the balance, as well as on the provability of hypotheses and theories about substances and substance transformations.

The work of Justus von Liebig on the mode of action of fertilizers founded agricultural chemistry and provided important insights into inorganic chemistry. The search for a synthetic substitute for the dye indigo for dyeing textiles triggered the groundbreaking developments in organic chemistry and pharmacy. In both fields, Germany had an absolute lead until the beginning of the 20th century. This lead in knowledge made it possible, for example, to obtain the explosive needed to wage the First World War from the nitrogen in the air instead of imported nitrates with the aid of catalysis (see Haber-Bosch process).

The autarchy efforts of the National Socialists gave further impetus to chemistry as a science. In order to become independent of petroleum imports, processes for liquefying hard coal were further developed (Fischer-Tropsch synthesis). Another example was the development of synthetic rubber for the production of vehicle tires.

In today's world, chemistry has become an important part of the culture of life. Chemical products surround us everywhere without us being aware of it. However, large-scale chemical industry accidents, such as those at Seveso and Bhopal, have given chemistry a very negative image, so that slogans such as "Get away from chemistry!" have become very popular.

At the turn of the 20th century, research developed to such an extent that in-depth studies of atomic structure no longer belonged to the field of chemistry, but to atomic physics or nuclear physics. This research nevertheless provided important insights into the nature of chemical transformation and chemical bonding. Further important impulses also came from discoveries in quantum physics (electron orbital model).

Albertus Magnus; fresco (1352), Treviso, Italy

Chemistry laboratory of the 18th century

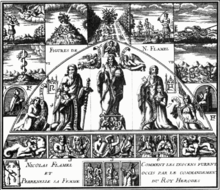

The "alchemical figures" of Nicholas Flamel

Search within the encyclopedia