Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V (Spanish Carlos I, French Charles Quint; * 24 February 1500 in Prince's Court, Ghent, Burgundy Netherlands; † 21 September 1558 in Cuacos de Yuste, Spain) was a member of the ruling house of Habsburg and Holy Roman Emperor.

After the early death of his father Philip I of Castile, Charles was sovereign of the Burgundian Netherlands, consisting of eleven duchies and counties, and from 1516 as Carlos I the first king of Spain, more precisely of Castile, León and Aragon in personal union. In 1519 he inherited the archduchy of Austria and was elected Roman-German king as Charles V; after his coronation in 1520 he initially bore (like his uncrowned grandfather Maximilian I and his future successors) the title "elected Holy Roman Emperor". In 1520 he was crowned Roman-German king in the imperial cathedral at Aachen by the archbishop of Cologne, Hermann V von Wied. In 1530 he was the last Roman-German king to be crowned emperor by Pope Clement VII, making him the second and last Habsburg to be crowned by a pope after Frederick III.

Charles pursued the imperial idea of the universal monarchy, according to which the emperor had priority over all kings. He saw himself as a peacekeeper in Europe, protector of the Occident against the expansion of the Ottoman Empire under Suleiman I, and defender and reformer of the Roman Catholic Church. In order to be able to enforce his hegemonic idea of rule, he led numerous wars against the French King Francis I (Italian Wars). In the process, Charles was able to rely financially on his colonial possessions in America (Viceroyalty of New Spain, Viceroyalty of Peru), but could not achieve his desired goal of a lasting weakening of France, which was temporarily allied with the Ottomans.

In the Holy Roman Empire, Charles V strove in vain to strengthen the power of the monarch vis-à-vis the imperial estates in the long term. Due to the Reformation, which began in 1517 and was partly supported by the estates, and Charles' frequent absences due to war, he was unable to prevent the spread of the Reformation movement. At times he tried to prevent the threatened confessional division of the empire by convening the Council of Trent (1545 to 1563), which, however, did not lead to the reconciliation of the religious parties, but after Charles's death became the starting point of the Catholic Counter-Reformation. After the failure of his efforts to reach a settlement with the Protestants, Charles attempted to dictate a solution to the religious conflict to the imperial estates in 1548 with the Augsburg Interim in the course of the Schmalkaldic War, which he had won. Due to the ensuing rebellion of the princes and the associated French invasion, he was forced to recognize a coexistence of the confessions in the Treaty of Passau (1552), which was regulated by the Religious Peace of Augsburg (1555).

With the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, written in 1532, Charles V issued the first general criminal code in the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1556, Charles resigned his sovereign offices and divided his dominions between his eldest son Philip II, who inherited the Spanish and Burgundian possessions, and his younger brother Ferdinand I, who had already received the Austrian hereditary lands in 1521 and to whom the title of emperor now also fell. This division split the House of Habsburg into a Spanish line (Casa de Austria) and an Austrian line (House of Habsburg-Austria). Charles died in 1558 in his palace next to the monastery of Yuste in Spain.

.jpg)

Titian: Charles V c. 1548 as Holy Roman Emperor, Sacrum Romanum Imperium (from 1520 to 1556). Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

Signature: "Yo, el Rey" (I, the King) rendered as Charles I of Castile

.svg.png)

Great coat of arms of Charles V from 1530 onwards

Live

Family and origin

The marriage of Maximilian of Austria to Mary of Burgundy in 1477 marked the beginning of the rise of the House of Habsburg as a major European power. As heiress to the Duchy of Burgundy, Maria was the richest bride of her time and the parties involved hoped that the union with the imperial house would provide support in the conflict against France (War of the Burgundian Succession) as well as a great increase in power for both dynasties. The marriage produced two offspring, Philip and Margaret, before Maria died in 1482 as a result of a riding accident.

Maximilian, from 1486 Roman-German king as Maximilian I, was now guardian and regent of his minor son in the Burgundian territories. It was not until the Treaty of Senlis (1493) that he succeeded in partially asserting his dynasty's claim to succession in Burgundy against France and in transferring the government of the Free County of Burgundy to his son.

As head of the family, Maximilian was anxious for Philip to marry in the most politically advantageous way possible and arranged a marriage to Spain. There, the Catholic kings Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile ruled. To cement the alliance, they arranged a double marriage in 1496/97 between Philip and Joan, the second eldest daughter of the royal couple, and between Margaret and the heir to the Spanish throne, John. After the deaths of her elder siblings (John in 1497, Isabella in 1498) and her nephew (Miguel da Paz in 1500), the various Cortes of the Spanish dominions recognized Joan and her husband Philip as heirs to the throne of the kingdoms of Aragon and Castile. During these years, Joan began to show symptoms of depression.

The marriage between Philip and Joan produced a total of six descendants. While Charles, Eleanor, Isabella and Maria grew up in the Netherlands, Ferdinand and Catherine lived in Spain.

- Eleanor (* 15. November 1498; † 18. February 1558)

- Charles (* 24. February 1500; † 21. September 1558)

- Isabella (* 18. July 1501; † 19. January 1526)

- Ferdinand (* 10. March 1503; † 25. July 1564)

- Mary (* 17 September 1505; † 17 October 1558)

- Catherine (* 14. January 1507; † 12. February 1578)

After the death of Isabella I, Joan succeeded her as Queen of Castile in 1504. Philip reached an agreement with Ferdinand II on the exercise of governmental power in the Treaty of Villafáfila (1506). Shortly after the treaty was signed, Philip died on September 25, 1506, plunging Joan into morbid gloom, earning her the nickname "the Madwoman." Her father took over the regency of Castile and in 1509 decreed her permanent residence in the castle of Tordesillas. Joan died on 12 April 1555 at the age of 75 in complete mental derangement. Through the marriage policy of his grandparents, Charles united the hereditary lines of four independent territories in his person:

- from Maximilian I: the Archduchy of Austria

- for Mary of Burgundy: the Duchy of Burgundy, the Burgundian Netherlands

- for Ferdinand II: the Crown lands of Aragon, including Naples, Sicily and Sardinia

- from Isabella I: the lands of the Crown of Castile with the newly conquered overseas territories

Youth in the Netherlands

Charles, Archduke of Austria, was born on February 24, 1500, at Prinzenhof, a residence in the Flanders trading city of Ghent. In memory of his paternal great-grandfather, the Burgundian Duke Charles the Bold, he was baptized Charles (Charles) by the Bishop of Tournai on 7 March 1500 in the Cathedral of St. Bavo in Ghent. His godparents were Margaret of Austria and Margaret of York, and Charles I de Croÿ, an adviser to his father. As early as 1501, Philip the Fair conferred the title of Count of Luxembourg on his son and made him a Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

Charles grew up effectively parentless. Alongside his sisters Eleonore and Isabella, Charles remained in the Netherlands while his parents travelled to Spain in 1502 to be sworn in as heirs to the throne. Shortly after their return, following the birth of Charles's sister Mary, they travelled to Spain permanently. When Philip died in 1506, Maximilian (Roman-German emperor from 1508) designated his daughter Margaret both regent in Burgundy and foster mother to six-year-old Charles and his sisters. Charles did not meet his mother again until 1517. With all vigour, Margarete brought up her nephew for succession and carefully prepared him for the princely tasks of his future life. The politically and intellectually highly gifted, but also art-loving governor lovingly brought up the children entrusted to her. She had them taught by Dutch and Spanish scholars. At her courts in Brussels and Mechelen, which were influenced by Flemish culture, she gathered artists and scholars who turned them into centres of Renaissance humanism.

In addition to his aunt, the theologian Adrian of Utrecht, rector of the University of Leuven (later Pope Hadrian VI), played an important role in the education of Charles; he laid the foundation for the piety and certainty of faith (devotio moderna) that characterized the character of his pupil throughout his life. In 1509 Emperor Maximilian appointed the nobleman Guillaume II de Croÿ as Grand Chamberlain and commissioned him to introduce Charles to political and court life. The emperor attached great importance to the teaching of chivalric virtues; for the ceremonial of Burgundy, one of the richest countries of the late Middle Ages, still lived in the tradition of medieval chivalric culture and was formative for the courtly society of the time. De Croÿ awakened in his pupil an interest in politics, educated him to work regularly and to fulfill his duties. Unlike the Anglophile Margaret, de Croÿ was careful to avoid hostilities with France.

Already in his youthful years, Karl showed essential character traits that were to shape his life: Appearing with sovereign dignity, he was surrounded by the aura of loneliness and became increasingly aloof as his life progressed. This tendency was supported by his pronounced Habsburg lower lip (progenia), which is said to have made it difficult for him to speak and breathe and increased his distance from his surroundings. In addition, Charles possessed great willpower, with which he controlled his often sickly and weak body. Much to the delight of his imperial grandfather, Charles demonstrated great skill and stamina in riding, fencing, shooting, hunting and in tournaments.

Besides French, the language of the Flemish aristocracy, Charles knew Latin and Dutch, had little knowledge of German and had to learn Spanish from 1517.

Burgundian and Spanish heritage

Due to pressure from the Dutch nobility and continuing tensions between Maximilian and Margaret, who had become too independent politically for the Emperor, the latter declared his grandson of age prematurely and ended Margaret's guardianship. The coming of age of Charles, Duke of Burgundy, was solemnly proclaimed before the States General at Coudenberg Palace in Brussels on 15 January 1515. Charles established his own court with the medieval ceremonial of Burgundy, while elsewhere nation-states of a modern character were already beginning to form. The festivities of homage were accompanied by tournaments, hunts and sumptuous banquets.

The following year, on 23 January 1516, Charles's maternal grandfather, Ferdinand II of Aragon, died. In his will, the latter had designated his daughter as his successor in the realms of the Crown of Aragon and Charles as regent. Charles, however, had himself proclaimed king of Castile and of Aragon, together with his mother, in appeals of different tenor. The hereditary claim of the House of Habsburg was recognized in Castile, but Charles was urged to accept the homage of the Spanish estates In Persona. Despite the admonitions of Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, Regent of Castile, more than a year and a half was to elapse before Charles acceded to the request to be officially recognized in Spain. Advised by Guillaume II de Croÿ, Charles first sought an understanding with the French king FrancisI in the Treaty of Noyon (13 August 1516). , to secure his position in Burgundy during his expected absence. This move was in keeping with the pro-French attitude of part of the Burgundian nobility, which included important advisers to Charles. Only after securing his rule by treaty did Charles travel to Spain with his sister Eleanor in September 1517. There they first visited their sick mother in Tordesillas, before Charles met his brother Ferdinand for the first time. To avoid rivalry, the latter soon left Spain, leaving the succession to his elder brother, and in turn went to the Netherlands to complete his education with Archduchess Margaret.

Charles and his Flemish court were perceived as foreigners in Spain, which is why he had to make concessions to the local nobility. These included the assurance that no money would be transferred abroad and that no offices or benefices would be granted to foreigners. Also, Charles, who used an interpreter, was asked to learn Spanish. Finally, in February 1518, the Castilian Cortes at Valladolid paid homage to the new king, and Aragon and Catalonia followed suit. Since Charles for the first time united the rule in the realms of the Crown of Castile and the Crown of Aragon, along with their tributary realms of Navarre, Naples, Sicily and Sardinia, in one person, he is considered the first king of Spain (as Carlos I). His domain also included the possessions in America as well as the Pacific region east of the Moluccas.

kingship

Charles V inherited four politically independent kingdoms from both sets of grandparents:

- of Ferdinand the Catholic: Aragon and the Italian possessions (Sicily, Naples and Sardinia).

- of Isabella the Catholic: Castile and the conquered overseas territories

- for Maximilian I: the Austrian Hereditary Lands

- for Mary of Burgundy: the Burgundian lands, that is the Free County of Burgundy (today's Franche-Comté) and the Burgundian Netherlands (essentially today's Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands).

Emperor Maximilian died in January 1519, leaving his grandson Charles, Duke of Burgundy and King of Spain, the Habsburg hereditary lands (the core of modern Austria) and a disputed claim to the title of Holy Roman Emperor. Before his death, Maximilian had been unable to settle the succession in the empire in terms of the House of Habsburg. In addition to Charles, Francis I of France and Henry VIII of England were competing for the title of Roman-German king and emperor. At the end of the election campaign, the Curia also brought Elector Frederick of Saxony into play, and Charles's brother Ferdinand was also considered as a candidate at times. However, even Charles' candidacy was not without controversy. Spanish circles feared that Charles's election would mean that the Iberian Peninsula would become marginal to his interests. The bid was pushed forward above all by the Grand Chancellor Mercurino Arborio di Gattinara, who had been in office since 1518, and who stylized Charles as the "German" candidate. This was by no means easy, since only one of Charles's ancestral lines reached back into the empire and he also hardly spoke any German.

The real contest took place between Charles and Francis I, which in its intensity surpassed all previous and subsequent elections of this kind. Both candidates advocated the imperial idea of a "universal monarchy" that would overcome the nation-state division of Europe. A dominant ruler was to secure peace within Europe and protect the Occident from the expansionist aspirations of the Muslim Ottomans ("Turkish danger"). The humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam, for example, was critical of this, but the idea of a unified Europe was certainly effective. In Charles' favour was the tradition of the Habsburg emperors, as whose natural heir he was regarded, and the importance of the dynasty in the empire. On the other hand, his possessions outside Germany made him considerably more powerful than his predecessors, and his previous centres of gravity lay outside the empire. Therefore, the imperial princes feared the monarch's superiority over the imperial estates; the French king, on the other hand, was not perceived as a threat. In the run-up to the election, Francis I had secured the electoral votes of the Elector and Archbishop of Trier and the Elector of the Palatinate, and had also offered 300,000 florins in election money. The Electoral College consisted of three ecclesiastical princes (the Archbishops of Mainz, Cologne and Trier) and four secular princes (the King of Bohemia, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg and the Count Palatine of the Rhine). These were at this election the archbishops Albrecht of Brandenburg (Mainz), Hermann V. of Wied (Cologne), Richard of Greiffenklau zu Vollrads (Trier) as well as the secular electors Ludwig II. (Bohemia and Hungary), Frederick III. (Saxony), Joachim I (Brandenburg) and Ludwig V (Palatinate). The wife of the King of Bohemia, Mary of Hungary, is a sister of the candidate Charles; the two electors, the Margrave of Brandenburg and the Archbishop of Mainz (at the same time also Imperial Chancellor), are two brothers from the House of Hohenzollern.

In this very difficult situation for Charles, the capital strength of the merchant Jakob Fugger decided the election in favour of the Habsburg. He transferred the outrageous sum of 851,918 florins to the seven electors, whereupon Charles was unanimously elected Roman-German king in absentia at St. Bartholomew's in Frankfurt on June 28, 1519. Thereafter, the Roman King was actually to be crowned Emperor by the Pope in Rome; however, the procedure was changed due to the political situation and the coronation of Charles V was carried out by Pope Clement VII in Bologna in 1530. Of the total sum, Jakob Fugger raised almost two thirds, namely 543,585 florins himself. The remaining third was financed by the Welsers (about 143,000 florins) and by three Italian bankers (55,000 florins each). These election funds are often understood as a bribe. However, the balancing of interests between the new king and the electors was not unusual in earlier and later Roman-German royal elections. The only noteworthy aspect was the amount in 1519, which resulted from uncertainty about the outcome of the election, and the compensation in money rather than in land, titles or rights. An electoral capitulation was negotiated between the electors and Charles's envoys - a new phenomenon in a royal election. The contents had almost the character of a fundamental law of the empire, such as the Golden Bull. In it, Charles accommodated the imperial estates on various points, including the government of the empire and foreign policy. For example, the establishment of an imperial regiment was promised, and all the regalia, privileges and imperial pledges of the imperial princes were confirmed. The fear of foreign domination was expressed in provisions that only Germans were to be appointed to important imperial offices and that foreign warriors were not to be stationed on imperial soil. The curia's demands for money were also to be limited and the large trading companies abolished.

Charles was crowned on October 23, 1520, in Aachen Cathedral by Archbishop Hermann V of Wied of Cologne, and subsequently called himself "King of the Romans, chosen Roman Emperor, always Augustus." Pope Leo X consented to the use of this title on October 26, 1520. Henceforth Charles bore the title:

We, Charles the Fifth, by the Grace of God chosen Roman Emperor, always Augustus, at all times Major of the Empire, in Germania, Castile, Aragon, León, both Sicily, Jerusalem, Hungary, Dalmatia, Croatia, Navarre, Granada, Toledo, Valencia, Galicia, Majorca, Seville, Sardinia, Cordoba, Corsica, Murcia, Jaén, Algarve, Algeciras, Gibraltar, the Canary and Indian Islands and the mainland, the Oceanic Sea &c. King, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, of Lorraine, of Brabant, of Steyr, of Carinthia, of Carniola, of Limburg, of Luxemburg, of Guelders, of Calabria, of Athens, of Neopatria, and of Württemberg &c. Count of Habsburg, of Flanders, of Tyrol, of Gorizia, of Barcelona, of Artois, and of Burgundy, &c. Count Palatine of Hainault, of Holland, of Zealand, of Pfirt, of Kyburg, of Namur, of Roussillon, of Cerdagne, and of Zutphen, &c. Landgrave in Alsace, Margrave of Burgau, of Oristan, of Goziani, and of the Holy Roman Empire, Prince of Swabia, of Catalonia, of Asturias, &c. Lord of Friesland and the Windisch Marches, of Pordenone, of Biscay, of Monia, of Salins, of Tripoli, and of Mechelen, &c.

Plus Ultra (Latin for "on and on") he declared to be his motto.

Charles V, who commanded an empire "in which the sun never set", was now deeply in debt to the Fuggers. In 1521 his debts to Jakob Fugger amounted to 600,000 florins. The Emperor repaid 415,000 florins by compensating the Fuggers through Tyrolean silver and copper production. When, at the Imperial Diet in Nuremberg in 1523, the Imperial Estates discussed a limit on trading capital and the number of branches of companies, Jakob Fugger reminded his Emperor of the electoral subsidy he had granted at the time: "It is also knowingly and evidently the case that Your Imperial Majesty could not have obtained the Roman crown without my intervention,...". With the simultaneous demand for immediate settlement of the outstanding debts, Jakob obtained from Emperor Karl that the considerations regarding the restriction of the monopoly were not pursued any further. In 1525 Jakob Fugger was also granted a three-year lease of the mercury and cinnabar mines in Almadén in Castile. The Fuggers remained in the Spanish mining business until 1645.

Organization of rule and self-image

The news of his election as king reached Charles near Barcelona. Here Charles, who had fled the plague, stayed in a monastery in Molino del Rey, 20 kilometres away. In 1520, in order to normalize relations with rulers who had lost out in the competition for the imperial throne, he traveled from Spain to England and the Netherlands on the occasion of his coronation. Charles's accession to power was associated with great hopes. Martin Luther wrote: "God has given us a young, noble blood for a head, and thus awakened many hearts to great good hope."

It never came to the construction of institutions that encompassed the entire ruling complex. The individual domains (territorialization) were held together solely by the person of the emperor, whose central task was to bring together the various components ("casas"). Charles exercised his rule less by attempting centralization than by coordination. Of importance were personal and also patronage relations, the court and the dynasty, which is why Charles V's court was one of the most complex of his time. In particular, the initial domination of the Burgundians caused resentment among the Spanish elites, who enjoyed special weight alongside the Burgundians. The emperor transferred Burgundian court ceremonial, which was charged with ecclesiastical sacredness, to Spain - this later became known as Spanish court ceremonial. Although the court unleashed its splendour on certain occasions, it was much weaker under Charles than under earlier Burgundian rulers. Emperor Charles was the last emperor without a fixed residence or capital. The multinational court, comprising between 1000 and 2000 people, moved between the individual territories, which is why the imperial cities in particular suffered greatly from the burdens this placed on them. In the German Empire, the members of the Spanish court were decidedly unpopular.

At the imperial level, Charles installed leading advisors or "ministers" at times, among the most important being Guillaume II de Croÿ and the Piedmontese jurist Mercurino Arborio di Gattinara. In military matters, Charles initially trusted Charles de Lannoy, who had already served his grandfather as an army commander. What role Charles himself played in the early days of his reign is not fully understood. Nicolas Perrenot de Granvelle and his son Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle later had much less influence. Around 1530 Charles decreed a division of responsibilities into two parts: Francisco de los Cobos y Molina was responsible for the Spanish territories, the overseas possessions in America, as well as Italy; in addition, there was a Burgundian secretariat of state for the Burgundian possessions under Granvelle, to which the office of imperial vice-chancellor was subordinate. The Archbishop of Mainz as Imperial Vice-Chancellor largely ceded his powers to Gattinara. In the last years of Charlemagne's reign, something like a cabinet responsible for the entire empire was created, but it proved ineffective.

To secure power in his wide-ranging, heterogeneous domain, Charles appointed family members as regents and governors in the Spanish lands, in the Netherlands, in the hereditary lands and also in the empire. According to the provisions of the Treaty of Worms (1521) and the Treaty of Brussels (1522), his younger brother Ferdinand was entrusted with the regency of the Austrian hereditary lands and the Duchy of Württemberg; in 1525 Charles ceded the last remnants of sovereign rights in the empire to Ferdinand. If necessary, Ferdinand represented the emperor in imperial affairs, and contact was maintained in writing. Tens of thousands of letters testify to the intensity of this communication, and Charles remained informed of events even in his absence and was able to issue appropriate instructions. This way of exercising rule was, however, made considerably more difficult by distance, especially as Ferdinand was initially granted little room for manoeuvre of his own.

Charles V saw the emperorship as the universal power of order in Europe above the individual states. His tasks included the defence against the infidels and the safeguarding of peace within the Occident. In addition, there was the protection, but also the reform of the church. The Grand Chancellor Mercurino Gattinara, with his conception of the emperor as dominus mundi, i.e. as a world monarch, strongly influenced Charlemagne's self-image.

Overseas possessions

→ Main article: Treaty of Saragossa

In order to finance his far-reaching power politics as well as his army and fleet, for which costs rose sharply, especially in the 1530s, Charles V was dependent not least on Spanish revenues. In the middle phase of his reign, Charles received as much as one million ducats per year from the Spanish possessions. The head of Spanish affairs Francisco de los Cobos y Molina built up an effective bureaucracy to collect the money. Soon, however, these were no longer sufficient. The conquistadors' shipments of gold and silver from the newly conquered lands in the Americas became more important. After the development of the silver mines of Potosí, 480 tons of silver and 67 tons of gold reached Spain in the years between 1541 and 1560. One fifth of the revenues from the Americas was due to the Crown, which is why Charles V's military campaigns would not have been feasible without the gold shipments of Hernán Cortés from New Spain and Francisco Pizarro from Peru. In Spain, work began on organizing the administration and exploitation of the new colonies. Seville became the monopoly port for traffic with America in 1525, and with the Council of the Indies the central authority of the colonies was also located there. In 1535 the viceroyalty of New Spain was proclaimed, and in 1542 the viceroyalty of Peru. The precious metal extracted served as a basis for bonds. Despite the high revenues, however, the income was not enough to cover the expenses of Charles's power politics. At times, the American possessions were pledged to creditors. Thus, in about 1527, what is now Venezuela came to the trading house of the Welsers, who exploited this territory until 1547. On the whole, the policy of borrowing greatly accelerated the indebtedness of Spain in particular.

Although the conquests were not centrally directed, Charles nevertheless promoted the policy of expansion and participated in the financing of Ferdinand Magellan's circumnavigation of the globe. Through the new possessions in America and in the Philippines named after his son and heir to the throne Philip (which, however, only formally became Spanish after Charles' death) in the Pacific, Charles V ruled over an empire of which he himself is said to have said that in it "the sun never set". Justifying the overseas conquests, in the Emperor's view, was the conversion of the pagans to Christianity. Also under the influence of Bartolome de las Casas, Charles tried to counteract the enslavement of the Indians through various decrees and laws. In the 1540s, a liberation of all Indians was even ordered. In the end, however, these attempts failed due to the conditions in the colonies and Charles' need for gold.

Diet of Worms 1521

→ Main article: Diet of Worms (1521)

The situation in the empire was difficult when Charles came to power. Unrest was spreading among the peasants and poorer city dwellers. The imperial knighthood was also restless. In particular, the Reformation movement around Martin Luther began to gain importance. Charles V initially followed his advisors from the circle of humanism in the matter of Luther and agreed to arbitration at the end of November 1520. Luther was excommunicated by the pope in 1521. The execution of the imperial sentence, which was customary in such cases, did not take place, since Luther was under the protection of the Elector Frederick the Wise. The latter demanded a clarification of the case on the basis of imperial law, without taking into account the Roman heresy trial. This called into question the previous relationship between the empire and the church. The Diet was the appropriate forum for clarifying the question. Charles settled for a compromise and invited Luther to Worms to recant his teachings there. If Luther stood firm, Charles threatened to execute the Eight. Between the Emperor and Pope Leo X, the Causa Luther was used for political purposes. It served as a means of pressure for the emperor to achieve a rapprochement with the Curia.

The first Imperial Diet in the time of Charles V took place in Worms in 1521. It focused on questions of imperial reform and how to deal with the Reformation movement started by Martin Luther. As far as questions of the imperial constitution were concerned, the conflict between the emperor and the imperial estates was initially about the power of government. This question had not been clearly resolved under Maximilian I, and the estates again demanded to be involved in the government by establishing an imperial regiment. Charles had also assured this in his electoral capitulation. Charles insisted, however, that the imperial regiment should take effect only in the absence of the emperor. In the Regimental Order adopted on 26 May 1521, he was largely able to get his way with this. Moreover, with his brother Ferdinand as governor and head of the imperial regiment, imperial influence was largely secured even in his absence. But in the end the decision was only a compromise between the estates and the monarchical principle. A conflict between the emperor and the imperial estates could therefore not be ruled out. Other questions that had to be clarified concerned the Imperial Chamber Court and the order of the territorial peace. With regard to the Imperial Chamber Court, which had fallen into crisis, a workable compromise was reached between the emperor and the imperial estates, which contributed to the court gaining in prestige and importance. Also with a view to the peace of the land, the execution of the court's judgments was transferred to the imperial districts. Thus the imperial districts were given a competence superior to that of the individual imperial estates. The imperial finances were also regulated and placed on a sustainable footing. Finally, the system of matriculation contributions was agreed upon as a means of financing. In principle, this regulation was valid until the end of the empire.

The Diet of Worms became famous because of the Luther question. What attitude the emperor had to Luther's positions before the Diet is not entirely clear. Personally, he seems to have had a quite differentiated relationship to the Reformation theses. However, after the verdict of the Roman heresy trial, he considered Luther to be convicted. Outside the empire, he had the writings banned and took action against Luther's followers.

In the run-up to the Imperial Diet, there had been negotiations on the part of the imperial court both with Electoral Saxony and with the Curia in Rome. Charles V and his advisors do not seem to have had a firm line at first. However, the emperor wanted to prevent the imperial estates from having a say in the question of the imposition of imperial sanctions. This he did not succeed in doing. Charles V felt compelled to assure Luther of safe conduct to Worms. On April 17, a first interrogation of Luther took place in the presence of the emperor. In another interrogation the next day, Luther refused to recant his writings until someone had refuted them on the basis of the Bible. After Luther's departure, Charles V issued a declaration on April 19 in which he professed allegiance to the millennial Christian tradition, loyalty to Rome, and protection of the Roman Church. He did not go into the content of Luther's teaching. After some time of preparation, Charles V issued the Edict of Worms on May 8, imposing imperial ban on Luther and banning his writings. However, he could no longer stop the Reformation movement with this, especially since Luther was brought to safety by Frederick the Wise at Wartburg Castle. In secret negotiations between Frederick and the imperial court, it was agreed that Saxony would not be officially served with the edict. The background for the imperial restraint was the disputes with France. All in all, the empire played only a secondary role for Charles at this time. Charles did not find a real understanding for the empire and its problems at the Imperial Diet.

Securing the rule in Spain, marriage

During his absence in Spain, Charles had entrusted his former teacher Adrian of Utrecht with the regency of Castile. Against this regency, which was perceived as foreign rule, the rebellion movement of the Comuneros developed in 1519, which was mainly supported by the bourgeoisie of the Castilian cities, especially Toledo. The Comuneros found support among sections of the clergy and nobility. Their aim was to limit royal power in favour of the Cortes. At the same time, a social revolutionary movement known as the Germanía occurred in the Kingdom of Valencia; there was no cooperation between the movements in the various Spanish territories. Concerned about the anti-feudal attitude of the insurgents in Valencia, much of the nobility sided with Charles, and the insurgents under Juan de Padilla were defeated at Villalar in 1521. Charles V travelled to Spain in person in the winter of 1521/22 to clarify the situation, and although he stressed that he would be lenient, he saw the rebellion as an offence against the divine order. There were several death sentences and confiscation of property. Among those executed was a bishop, which made Charles fear excommunication. Even though papal absolution arrived some time later, the executions kept Charles very busy until his death. During his reign, Charles managed to limit the political influence of the high nobility without touching their other privileges, thus securing their allegiance. The Spanish Inquisition, which acted primarily against Jews and Muslims who had converted to Christianity and their descendants, remained in operation under Charles V. With regard to the need to fight heretics and defend Catholicism, Charles and the leading forces in the Spanish territories were in agreement. After securing power in favor of the crown, Spain became a central power base for the emperor.

Charles had been engaged to Mary Tudor, daughter of the English King Henry VIII, since 1522. However, partly because of financial advantages, he decided to marry Isabella of Portugal, the daughter of the Portuguese King Manuel I. The wedding took place on 10 March 1526 in the magnificent Alcázar of Seville. Because Isabella's mother Maria was also an aunt of Charles V, and thus the imperial spouses were first cousins, they required a dispensation for the marriage, which Pope Clement VII also granted. The people cheered the graceful Portuguese woman, who thanked them in the purest Castilian for the endless ovations and thus immediately won the hearts of the masses. Although the marriage of the imperial couple had been purely politically motivated, they quickly fell in love with each other and led an extremely happy marriage, which is also documented for posterity in the form of numerous letters between the two. Charles V always showed his wife a courtly reverence that went far beyond the usual level.

In the summer of 1526, the newlyweds moved from Seville to Granada and lodged there in the Alhambra until the end of the year. The emperor was therefore even reprimanded by members of the Council of State not to extend his honeymoon too long.

_Karel_V_-_Koninklijk_klooster_van_Brou_25-10-2016_10-06-36.jpg)

Young Charles around 1520 (painting by Bernard van Orley)

Charles as a youth (detail from a family painting by Bernhard Strigel, ca. 1516)

_Flemish.tiff.png)

The painting of Charles around 1514/16 clearly shows his Habsburg lower lip

European dominion of Charles V, after his election in 1519 Castile (wine red) Possessions of Aragon (red) Burgundian possessions (orange) Austrian hereditary lands (yellow) Other territories of the Holy Roman Empire (pale yellow) which, apart from the Austrian and Burgundian possessions, belonged to Charles' dominions.

_-_Isabel_van_Portugal_(ca.1550)_-_Lisboa_Museu_Nacional_de_Arte_Antiga_19-10-2010_16-12-65.jpg)

Isabella of Portugal

Execution of the Comuneros (oil painting by Antonio Gisbert, 1880)

Martin Luther at the Diet of Worms (coloured woodcut, 1557)

"Allegory of Emperor Charles V as Ruler of the World" (painting by Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1604). The saying: "In my kingdom the sun never sets" is attributed to Charles V.

Coronation in Aachen (woodcut, 1520)

_by_Hans_Maler_zu_Schwaz.jpg)

Charles' younger brother Ferdinand, deputy in the realm (Hans Maler zu Schwaz)

Mercurino Gattinara, painting by Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen (c. 1530)

,_1519.jpg)

A handwritten letter from Charles to Margrave Casimir of Brandenburg-Kulmbach dated May 2, 1519, concerning the upcoming election of the king. Nuremberg, State Archives, Ansbach Archives 13834

Child's portrait of the seven-year-old Charles (painting by the Master of the Magdalen Legend, c. 1507)

Philip the Fair (painted by Juan de Flandes)

Joan the Mad, Juana I de Castilla (painted by the master of the Joseph sequence)

European power politics

→ Main article: Italian Wars

War until the Peace of Madrid (1520-1526)

In order to assert Charlemagne's claim to the emperorship as a superior, supranational European regulatory power, a power superior to the other states was needed. Prosperous Italy played a central role in this, because if he succeeded in gaining significant influence there, European hegemony was possible. In addition, the emperor wanted to regain for the House of Habsburg the Duchy of Burgundy, which had fallen to France in 1477, since his Burgundian ancestors were buried in Dijon. His testamentary wish of 1522 emphasized the importance of Burgundy to Charles by directing that he be buried alongside his ancestors in the Chartreuse de Champmol of Dijon. With this nostalgic aspiration, he challenged the compromise of the division of the Burgundian inheritance of 1493 (Treaty of Senlis). Furthermore, Charles V wanted to end the French feudal rights in the county of Flanders and Artois and also claimed the southern French territories of Provence and Languedoc as imperial fiefs.

These territorial claims brought Charles into conflict with the power-conscious French King Francis I, who was unwilling to yield to the claims. He also harboured hegemonic aspirations in Italy: After a military victory over the Swiss, large parts of Upper Italy and especially the Duchy of Milan had fallen to France in 1515; in addition, he harboured claims to the Kingdom of Naples and the parts of the Kingdom of Navarre that had fallen to Spain in 1512.

As early as 1520, Charles had obtained the acquiescence of the English King Henry VIII for his planned war against France, and a year later he was able to win the Pope for an anti-French alliance. At first Henri d'Albret, who was living in exile in France, marched into Spanish Navarre, but was forced to withdraw after a few weeks; there were also skirmishes on the Dutch-French border. In the second half of 1520, the direct confrontation between Charles V and Francis I began in Champagne as well as in Upper Italy; in November 1520, Henry VIII also entered the war on the side of the emperor. Initially the imperial troops were successful, and by May 1522 large parts of northern Italy were in the emperor's hands. The House of Sforza regained Milan as an imperial fief, Duke Charles III de Bourbon-Montpensier fell from the French king, but plans to acquire his own territory at the expense of the French crown failed and he was forced to flee into exile at the imperial court. Because of Charles V's strong position, an anti-Emperor sentiment developed in Italy, and the Pope and the Republic of Venice leaned more and more toward France. French troops, for their part, were now beginning to achieve military success. An English invasion of France failed, as did the imperial advance into Provence in 1524. In turn, the French succeeded in conquering Milan and besieging Pavia, which meant that they now controlled almost all of northern Italy. Finally, on February 24, 1525, Charles V's troops scored a decisive military victory at the Battle of Pavia and were able to capture the French king.

Francis I arrived as a prisoner in Barcelona on 19 June 1525 and was taken to Madrid in July. How to deal with the captured king and the power-political advantageous situation was disputed between Charles and his advisors. Gattinara would have preferred to have him killed; a de facto break-up of France was also in his mind. Charles V, however, went along with the proposals for a moderate peace. It was not until November 1525 that Francis agreed to the emperor's demands on condition that he could not surrender Burgundy until he returned to France. In the Peace of Madrid (14 January 1526), Francis I renounced the Duchy of Milan as well as the feudal sovereignty in Flanders and Artois. He did not, however, yield to the demand that he should also renounce his claims in Burgundy. The release of the French king was to be made with the abandonment of his two sons, who were housed under unfavourable conditions in various Castilian fortresses until the Peace of Cambrai (1530).

On the part of the emperor, the peace terms were intended as a mild gesture of reconciliation, and the promise to give his sister Eleonore to the French king as a wife was also aimed in this direction. Charles hoped to persuade Francis to fight together against the Ottomans and the Lutherans, and the Habsburg appealed to "gloire" - chivalric honour - to abide by the treaty and released Francis from captivity - against the advice of his advisers. On the French side, however, the peace was not regarded as moderate, but as a peace of submission.

War against the Holy League of Cognac (1526-1529)

After his release from Spanish captivity and return to Paris, Francis I revoked the provisions of the Peace of Madrid, claiming that he had acted under duress. He succeeded in creating a broad anti-Imperial alliance between France, Pope Clement VII, the Republic of Venice, Florence and finally Milan (Holy League of Cognac). The Duchy of Bavaria was also part of the anti-Habsburg opposition. Even before this, Francis had come to an understanding with Henry VIII and hostilities broke out again. When an Ottoman army threatened the Austrian hereditary lands in 1526, the situation became threatening for Charles V.

The expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the early modern period meant a long-term shift in the European balance of power. The conquests of the Ottoman forces along the Mediterranean coast and on the Balkan Peninsula in the direction of Vienna threatened Habsburg rule in the hereditary lands as well as peace in Europe. In 1521 the Ottomans conquered Belgrade, and in 1526 they defeated the HungarianKing Louis II at the Battle of Mohács. The death of Louis gave the House of Habsburg, in the person of Ferdinand, hereditary claim to the crowns of Bohemia and Hungary. Now the Ottomans threatened Ferdinand's rule in Hungary (First Austrian Turkish War) and besieged the city of Vienna in 1529 with a force of 120,000 men. Emperor Charles, however, was militarily tied up due to his campaigns in Upper Italy and could not support his brother Ferdinand, who was ultimately only able to rule a part of Hungary.

The war against France increasingly overstretched the imperial finances. The lansquenets in northern Italy were dissatisfied with their pay, and when their commander Georg von Frundsberg tried to prevent an impending mutiny, he suffered a stroke. The Lansquenets then moved against Rome, which they regarded as the "Whore of Babylon". When Charles of Bourbon fell in the storming of the city on May 5, 1527, the leaderless imperial lansquenets sacked the city at the infamous Sacco di Roma. Pope Clement VII had taken refuge in Castel Sant'Angelo and surrendered in early June 1527. Once again an adversary was in the hands of the imperials, and once again Charles V prevailed with lenient treatment of his opponent. Although Charles was not responsible, the event was seen as evidence of the Emperor's threat to the papacy and the Emperor's violent policies in Italy. The events of the Sacco di Roma strengthened the anti-imperial forces in Italy and Charles came under pressure. The latter guaranteed the Republic of Genoa its independence, causing Andrea Doria to side with the Genoese fleet and cut off the supply routes of French troops in Italy. The forces of the League of Cognac suffered military defeats and Francis I had to make peace again.

The Ladies' Peace of Cambrai, negotiated on 5 August 1529, sealed France's renunciation of claims in Italy. The renunciation of French feudal claims in Flanders and Artois was confirmed, while the Emperor, for his part, withdrew from the claim to the Duchy of Burgundy. With the peace, the supremacy of the House of Habsburg was secured until the end of the 16th century. In the peace of Barcelona Charles granted favourable terms of peace to the pope and concluded a defensive alliance with him. However, Charles was unable to enforce the holding of a council for church reform. The reconciliation with the Pope led to Charles receiving the Iron Crown of the Lombards from the hands of Clement VII on 22 February 1530, who crowned him Roman Emperor in the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna on 24 February 1530. Charles V was thus the last Roman-German emperor whose rule was confirmed by coronation by the Pope.

Battles against Ottomans and French (1532)

The peace, however, was short-lived. In 1532 there was a new great campaign against the Ottomans. Charles V himself took part in this, without this war having brought a decision. Charles returned to Spain to start a "crusade" against the Ottomans from there. The fight on the continent, however, he left to his brother.

The relationship with Pope Clement VII, who was increasingly aligned with France, deteriorated. Henry VIII also turned more against the Habsburgs. However, Francis I did not succeed in forming an anti-Emperor alliance with the German Protestants. The French, on the other hand, had been allied with the Barbary and the Ottomans since 1534. Overall, Charles was unable to decisively weaken the Ottoman-French alliance. But neither did the French succeed in revising the results of the Peace of Cambrai. On the contrary, after the extinction of the Sforza, Charles succeeded in seizing Milan as an imperial fief and granting it to his son Philip. Charles won an important victory in 1535 by conquering Tunis in the Tunis campaign. It was the first time that the emperor personally took part in a battle. The victory increased his prestige in Europe. From Tunis he visited the Kingdom of Naples, including the Charterhouse of San Lorenzo di Padula, and moved from there to Rome. His entry there resembled a triumphal procession. However, the power of the barbarians was by no means broken. Francis I conquered Turin. Charles V made a long speech at the Vatican on Easter Monday, accusing the French king of a breach of the peace, and appealing to the pope to act as arbiter. Intended also as a propaganda measure for the Italian public, this did not succeed with the Pope. At least the latter accommodated him on the council question. On the advice of Andrea Doria, Charles decided to launch a counter-offensive towards Marseilles. The attack on the city failed and the imperial army had to return to Lombardy. Meanwhile, the cooperation of the French with the Ottomans encouraged the Pope's rapprochement with Charles. In 1538 a league directed against the Turks was concluded between Charles, his brother Ferdinand, Venice, and the pope. In the same year, Pope Paul III brokered the ten-year Nice truce between Charles V and Francis I. This established the status quo in Italy. After a meeting between Charles and Francis I, a reconciliation even seemed possible for a time.

War against France until the Peace of Crépy (1540-1544)

Already since 1540, Charles and Francis I began to prepare diplomatically for the next round of arms. The situation intensified when the French envoys sent to Istanbul were murdered by Spanish soldiers on their return. Although the emperor denied involvement, he had some complicity. Instead of helping his brother on the Hungarian front, Charles ordered a fleet expedition to Algiers in 1541, but the sinking of numerous ships in a storm caused it to fail. Francis I, still allied with the Ottoman Empire, declared war on Charles in 1543. This time, the latter relied on a defensive concept and was thus successful against the French advances (see also: Siege of Nice (1543)). France's alliance with Denmark and Sweden had little significance. Charles entered into an alliance with Henry VIII in 1543. Instead of seeking decision in the Mediterranean, Charles shifted the focus of his efforts to Central Europe. The defeat of Duke William of Cleves, who was allied with France, caused Francis I to lose his last ally in the empire. In 1544 the emperor and the imperial estates agreed on a policy against France. Charles then advanced into French territory. However, the advance failed because of the enemy's stalling tactics and the country's fortresses. Henry VIII essentially confined himself to the siege of Boulogne. The army began to disintegrate due to lack of pay. An advance to Paris could therefore not take place. Nevertheless, the danger induced Francis I. to a truce in 1544 in the Peace of Crépy. Francis I contractually renounced future attempts at alliance with the Protestant estates in the empire and undertook to send participants to a council on imperial soil.

Last foreign wars

The new French King Henry II had been working towards a new offensive alliance with the Ottomans since 1550. He intended to persuade the Sultan to break the truce concluded with Ferdinand in 1547. Charles disgruntled the High Porte with his action against a pirate leader in the Mediterranean who was also a Turkish vassal. As a result, Ferdinand's negotiations with the Turks failed, and a two-front war in Italy and Hungary loomed. Henry II also formed an alliance with the Protestant opposition in the empire. In the Treaty of Chambord, which was invalid under imperial law, Henry II undertook to cut off Charles's connection with his troops in the Netherlands. He was also to pay substantial subsidies to the princely opposition. In return he was to receive the cities of Metz, Toul, Verdun and Cambrai as imperial vicars. Henry then occupied the above cities with an army of 35,000 men in the so-called Trois-Évêchés. Charles attempted to regain the cities after reaching an agreement with the opposition. He laid siege to the city of Metz, which was strategically located on the line connecting the Netherlands and Italy. The fortress was almost impossible to take with the resources of the time and was also well defended. The siege therefore failed with high losses. The campaign was immensely costly at two and a half million ducats; this was twice the annual revenue of Spain. As damaging as the defeat before Metz was to Charles's reputation, it did not mean defeat or the end of the war altogether. Rather, the imperials resumed fighting from 1553 onward in both Italy and the Netherlands. Peace was not concluded until after Charles's abdication.

Siege of Metz

.jpg)

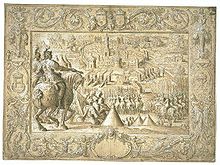

Siege of Nice from 1543

Charles V announces the victory in Tunis to the Pope in 1535

.jpg)

Solemn entry of Charles V and Francis I in Paris in 1540

The Sack of Rome, Sacco di RomaPainting by Johann Lingelbach from the 17th century

Battle of Pavia 1525 (oil painting by Ruprecht Heller, 1529)

Francis I (portrait by Jean Clouet, 1527)

Questions and Answers

Q: Who was Charles V?

A: Charles V was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1519, King of Castile and Aragon from 1516, and Lord of the Low Countries as Duke of Burgundy from 1506.

Q: Who were Charles V's parents?

A: Charles V's parents were Philip the Handsome and Joanna the Mad.

Q: Which countries did Charles V rule?

A: Charles V ruled Austria, Spain, Two Sicilies, Sardinia, Germany, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, Hungary, Bohemia, Croatia, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela.

Q: When and how was he addressed as "His Majesty" or "His Imperial Majesty"?

A: Charles V was first addressed as "His Majesty" or "His Imperial Majesty" when he became king.

Q: What was his Empire known for?

A: Charles V's Empire was known as "in which the sun does not set."

Q: What was Charles V known as?

A: Charles V was known as "The Emperor of Universal Dominion."

Q: How did Charles V divide his empire?

A: Charles V divided his empire between his brother Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor and his son Philip II of Spain.

Search within the encyclopedia