Cetacea

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Wale (disambiguation).

![]()

Cetacea is a redirect to this article. See also: (2089) Cetacea or Cetacea Rocks.

The whales (Cetacea) form an order of mammals with about 90 species that live exclusively in the water. Two suborders are distinguished: the baleen whales (Mysticeti), which feed on plankton as filter feeders and include the largest animals in evolutionary history, and the predatory toothed whales (Odontoceti), which also include the family of dolphins (Delphinidae). The term "cetacean" in a linguistically narrower sense may exclude the species referred to as "dolphin" (which are not entirely congruent with the family), so that the whole order is also referred to as "whales and dolphins".

The old name "whale", initially dominant in New High German and now popular, does not correspond to today's scientific understanding, since whales are not fish, but aquatic (water-living) mammals (marine mammals). In antiquity and until the middle of modern times, however, they were regarded as fish, going back to Aristotle, although the philosopher of the fourth century B.C. had already recognized many physiological similarities with terrestrial vertebrates. It was not until 1758 that Carl von Linné classified whales as mammals.

With the exception of individual dolphins and the various groups of river dolphins, cetaceans live in the sea. This group of mammals made the transition to aquatic life about 50 million years ago in the early Eocene. Whales are closely related to the artiodactyls (Artiodactyla), both groups together forming the taxon Cetartiodactyla. The populations of many whale species have declined significantly as a result of pollution, fishing and industrial whaling.

Features

General

Whales, along with manatees, are the only mammals fully adapted to life in the water. They are unable to survive on land. In stranded whales, body weight compresses their lungs or breaks their ribs due to the lack of support from the buoyancy of the water. Smaller whales die of heat stroke because of their good thermal insulation. The body structure of whales is adapted to their habitat, yet they continue to share essential features with all other higher mammals (Eutheria):

- Whales are air breathers and have lungs. Depending on the species, they can stay submerged from a few minutes to more than two hours (for example, sperm whale).

- Whales have a particularly powerful heart. This distributes the oxygen absorbed in the blood very effectively in the body.

- Whales belong to the same-warm animals, i.e. they hold a constant body-temperature, independent of the environment, in contrast to the change-warm animals.

- Whales give birth to fully developed calves and suckle them with extremely fat-rich breast milk from special mammary glands. Embryonic development takes place in the mother's body. During this time, the embryo is nourished by a special nutrient tissue, the placenta.

Whales include the largest animals that have ever lived on Earth. The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is the largest known animal in Earth's history, with a body length of up to 33 meters and a weight of up to 200 tons. The sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) is the largest predatory animal on earth. The smallest whale species, on the other hand, only reach a maximum body length of about 1.5 metres, such as the La Plata dolphin, the Hector's dolphin and the California porpoise.

Whales are also characterized by an unusual life expectancy for higher mammals. Some species, such as the bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus), can reach an age of over 200 years. Based on the annual rings of the bony ear capsule, the age of the oldest known specimen, a male, was determined to be 211 years at the time of its death.

External anatomy

The body outline of whales resembles that of large fish, which can be attributed to the way of life and the special conditions of the habitat (convergence). Thus, they have a streamlined shape, and their front extremities are transformed into fins (flippers). On their backs they carry another fin, called a fin, which takes on different shapes depending on the species. In a few species it is completely absent. Both the flippers and the fin are used solely to stabilize the whales in the water and for steering. The tail ends in a large caudal fin called the fluke, which, like the fin, is a cartilaginous surface with no bony parts. The fluke attaches horizontally instead of vertically to the body, a distinguishing feature from fish that is very recognizable from the outside. It enables locomotion through vertical flapping.

The hind legs are completely missing from the whales, as well as all other body appendages that could hinder the streamline shape, such as the ears and also the hair. The male genitalia and the mammary glands of the females are sunk into the body.

All whales have an elongated head, which takes on extreme proportions, especially in the baleen whales, due to the widely projecting jaws. The nostrils of the whales form the blowhole, one in toothed whales, two in baleen whales. They lie on the top of the head so that the body can remain submerged when breathing. When exhaling, the moisture in the breath usually condenses and forms what is known as the blow. In toothed whales, a connective tissue melon exists as a head bulge. This is filled with air sacs and fat and helps with buoyancy as well as sound formation. The sperm whales have a particularly pronounced melon; here it is called the spermaceti organ and contains the spermaceti or spermaceti that gives it its name. The jaws contain a varying number of teeth in toothed whales, from two flat tusks in two-toothed whales to a large number of uniform (homodont) teeth in dolphins. The long tusk of the male narwhal is also a remodeled canine. With the baleen-whales, long horny filter-plates, the baleen, sit in the upper jaw instead of the teeth.

The body is encased in a thick layer of blubber. This serves as heat insulation and gives the whales a smooth, streamlined body shape. In the larger species, the blubber can reach up to half a metre in thickness. The very special structure of the skin above the blubber layer gives rise to a phenomenon known as Gray's paradox: the body of faster swimmers in particular, such as dolphins, actually has far better streamlining properties than a solid body of the same shape. This is attributed to the damping property of the skin, which mitigates disturbing vortex formations. For this purpose, the dermis has long papillae that form a seam and are interlocked with the overlying epidermis. The papillae of the dermis are located on lamellae that are largely transverse to the longitudinal axis of the body and thus also to the direction of flow. Because of their length, the papillae were first thought to be the excretory ducts of sweat glands. Today, however, their real function is known and it is also known that whales do not possess any skin glands with the exception of the mammary glands. In addition to these attenuating structures, the skin has a microscopically fine relief pattern. Based on the results of physiological experiments, an active response of the skin is also assumed. The optimization of the flow properties could be reproduced in experiments with artificial whale skin.

Skeleton

The whale skeleton gets along largely without compact bones, because it is stabilized by the water. For this reason, the compact bones common in land mammals are replaced by fine-meshed cancellous bones. These are lighter and more elastic. In many places, bone elements are also replaced by cartilage and even fatty tissue, further improving the hydrostatic properties of the whale body. In the ear and snout, there is a form of bone found only in whales with an extremely high density, reminiscent of porcelain. This has special acoustic properties and conducts sound better than other bones.

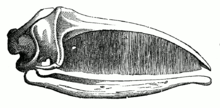

The skull of all whales is characteristically elongated, which is well visible in the baleen whale shown here. The jaw and nasal bones form a protruding rostrum. The nostrils are located at the top of the head above the eyes. The posterior part of the skull with the cranium is markedly shortened and deformed. Due to the displacement of the nostrils to the top of the head, the nasal passages run vertically through the skull. In toothed whales, the larynx extends beak-like into this passage, while in baleen whales, the larynx is deflected to the side of the passage. The teeth or the baleen sit in the upper jaw exclusively on the maxillary bone. The cranium is narrowed forward by the nasal passage and is correspondingly higher, with individual skull bones pushing over each other (telescoping). The bony ear capsule, the petrosum, is only connected to the skull by cartilage so that it can vibrate independently of the skull. For this reason, isolated ear capsules represent common whale fossils called cetoliths. In many toothed whales, the skull is also asymmetrical due to the formation of a large melon and several air sacs.

Depending on the species, the number of vertebrae in the spine is between 40 and 93 individual vertebrae. The cervical spine, as in almost all mammals (exceptions: sloths and round-tailed manatees), consists of seven vertebrae, which in most whales, however, are greatly shortened or fused together, providing stability when swimming at the expense of mobility. The ribs are supported by the thoracic vertebrae, which can range in number from 9 to 17. The sternum is only cartilaginous and strongly receded. The last two to three pairs of ribs are not connected to the sternum in all whales and lie free in the body wall as fleshy ribs; in baleen whales, all ribs except the first pair lie free. This is followed by the stable lumbar and caudal part of the spine, to which all further vertebrae belong. Below the caudal vertebrae, the chevron bones have developed from the hemal arches of the vertebrae, which provide additional attachment sites for the tail muscles.

The front limbs are paddle-shaped with shortened arm bones and elongated finger bones to aid locomotion. They are fused by cartilage. On the second and third fingers, there is also an increase in the number of phalanges, a condition known as hyperphalangia. The only functional joint is the shoulder joint, all others are immobile (except in Amazon river dolphins (Inia)). A clavicle is completely missing. Since locomotion of the cetacean on land is no longer necessary and would not be possible in the larger species due to body weight, the hind limbs are severely atrophied and exist only as skeletal rudiments without connection to the spine.

Internal anatomy and physiology

Particularly important for the way of life of whales in the water is the structure of the respiratory and the circulatory system. The oxygen balance of the whales is correspondingly highly effective. With each breath, a whale can exchange up to 90 percent of the total air volume of the lungs, in a land mammal this value is about 15 percent. In the lungs, the lung tissue extracts about twice as much oxygen from the inhaled air as in a land mammal. The lungs themselves contain a double capillary network in the alveoli. Oxygen is stored in various tissues of the cetacean besides the blood and lungs, most notably in the muscles, where the muscle pigment myoglobin provides effective binding. This lung-external oxygen storage is essential for survival during deep diving, since from a diving depth of about 100 meters the lung tissue is almost completely compressed by the water pressure. During the diving process, oxygen consumption is massively reduced by lowering heart activity and blood circulation, and individual organs are not supplied with oxygen during this time. Some rorquals can dive up to 40 minutes, sperm whales between 60 and 90 minutes and duck whales even two hours. The diving depths are on average about 100 meters, sperm whales dive up to 3000 meters deep.

The stomach of whales consists of three chambers. The first area is formed by a glandless and very muscular forestomach (which is missing in beaked whales), followed by the main stomach and the pyloric stomach, both of which are equipped with glands for digestion (see ruminants, there animals with similar digestive systems). Attached to the stomachs is an intestine, the individual sections of which can only be distinguished histologically. The liver is very large and has no gall bladder.

The kidneys are strongly flattened and very long. They are divided into several thousand individual lobules (reniculi) in order to function effectively. The salt concentration in the whales' blood is lower than that in seawater; the kidneys therefore also serve to excrete salt. This allows the whales to drink seawater.

Commonalities in chromosome genetics

The original karyotype of whales contains a chromosome set of 2n = 44. They have four pairs of telocentric chromosomes (chromosomes whose centromere is located at one of the telomeres), two to four pairs of subtelocentric chromosomes and one to two large pairs of submetacentric chromosomes. The remaining chromosomes are metacentric-that is, have the centromere about in the middle-and are rather small. In the sperm whales (Physeteridae), the beaked whales (Ziphiidae) and the right whales (Balaenidae), there was a convergent reduction in chromosome number to 2n = 42.

.jpg)

caudal fin

Freely prepared skeleton of a blue whale in front of the Long Marine Laboratory in Santa Cruz, California.

Weathered skull with upper jaw of a toothed whale (sperm whale) in Kongsmark on Rømø, Denmark

Skull of a baleen whale

Skeleton of a baleen whale (without baleen)

Distribution and habitat

Whales are primarily marine animals and can be found in all seas of the world. Some species swim thereby also into the river deltas and even into the rivers. Only a few species, on the other hand, live exclusively in freshwater, and these are several species of different families known as river dolphins. While many marine species of cetaceans, such as the blue whale, the humpback whale and also the killer whale, have a range that encompasses almost all oceans, there are also individual species that occur only locally. These include the California porpoise in a small part of the Gulf of California and the Hector's dolphin in some coastal waters near New Zealand. In the oceans, there are species that prefer the deeper marine areas as well as species that frequently or exclusively live near the coast and shallow water areas.

The division of habitats normally occurs along specific temperature boundaries in the oceans, and accordingly the distribution areas of most species lie along specific latitudes. Accordingly, many species live only in tropical or subtropical waters, such as the Bryde's whale or the round-headed dolphin, while others are found only in the southern (such as the southern right whale or the hourglass dolphin) or northern polar seas (the narwhal and the white whale). This vertical dispersal is mainly interrupted by land masses as natural barriers. Thus, individual populations of many cosmopolitan species exist in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans; moreover, some species occur basically only in one of these three separate oceans. For example, the Sowerby's toothed whale and the Clymene's dolphin are found only in the Atlantic Ocean, and the white-striped dolphin and the northern right whale dolphin are found only in the North Pacific Ocean. In addition, migratory species, whose breeding grounds are often in tropical regions and whose feeding grounds are in polar regions, develop southern and northern populations in both the Atlantic and the Pacific, which are genetically separated by the migrations. For some species, this separation of populations eventually leads to the formation of new species, such as the southern right whale and the two northern right whale species in the Atlantic and Pacific.

A total of 32 cetacean species have been identified in European waters, including 25 species belonging to the toothed whales and seven belonging to the baleen whales.

killer whale in the Arctic

Search within the encyclopedia