Carnival

![]()

This article is about the custom of carnival.

- For details of the tradition of the parades see carnival parade

- For the Japanese manga series see Carnival (manga)

- For the Polish historian see Adam Fastnacht

Carnival, Fastnacht, Fassenacht, Fasnacht, Fasnet, Fasching, Fastabend, Fastelovend, Fasteleer or the fifth season are the customs with which the time before the forty-day Lent is celebrated exuberantly. Lent begins on Ash Wednesday and serves as preparation for Easter.

Carnival is celebrated in very different ways: Carnival parades, music, masks and dressing up play a role. The carnival in Latin America, for example the carnival of Oruro or the carnival in Rio, developed its own vitality. Also well known are the carnival in Venice, in Canada the carnival of Quebec, the mid-Lenten carnival on Sunday Laetare in Stavelot and other places in the Belgian eastern cantons, and in Spain the carnival of Santa Cruz de Tenerife and the carnival in Cadiz. There is also a distinct Mardi Gras tradition in the southern states of the United States. In New Orleans, for example, the French name Mardi Gras (Fat Tuesday, Shrove Tuesday) is used. Carnival in Namibia takes place in various places in the country and no longer has any temporal reference to Lent. In the German-speaking world, the "strongholds" are the Rhineland and the Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht.

History

Ancient

Precursors of the carnival were already celebrated 5000 years ago in Mesopotamia, the country with the first urban cultures. An ancient Babylonian inscription from the 3rd millennium BC tells us that under the priest-king Gudea a seven-day festival was celebrated after the New Year as a symbolic wedding of a god. The inscription says: "No grain is milled on these days. The slave is equal to the mistress and the slave to his master's side. The mighty and the lowly are equal." Here, for the first time, the principle of equality is practiced in boisterous celebrations, and this remains a characteristic feature of Carnival to this day.

In all cultures of the Mediterranean area, similar festivals can be traced, which are mostly connected with the awakening of nature in spring: In Egypt, the exuberant festival was celebrated in honor of the goddess Isis, and the Greeks held it for their god Dionysus and called it Apokries.

Finally, the Romans celebrated the Saturnalia from 17 December to 19 December in honour of their god Saturnus. The festival was associated with a public feast to which everyone was invited. Executions were postponed because of the Saturnalia. Slaves and masters temporarily exchanged roles, celebrated and sat together at the table, garlanded with myrtle, drank and ate, dared to speak freely and showered each other with small roses. The roses may have given rise to the confetti we know today. The Romans were already organising colourful parades in which a decorated ship's carriage was pulled around.

However, current research strongly doubts dates such as Saturnalia or Lupercalia as the origin of carnival customs. In many masks, figures and customs, pre-Christian rites, for example those of the Celtic religion, seem to have been preserved, which involve the change from the cold winter half-year to the warm and fertile summer half-year. People tried to drive away the winter by dressing up as ghosts, goblins and sinister figures from nature and beating wildly with wooden sticks or making noise with a rattle. In carnival customs in Tyrol and South Tyrol, the symbolization of the struggle between light and darkness, between good and evil, between spring and winter still takes place. Examples of this are the Egetmannumzug in Tramin or the Mullerlaufen in Thaur.

Germanic theories (so-called continuity premises) were particularly popular during National Socialism, but are still quoted today, sometimes unconsciously. The scepticism towards all theories that assume a tradition of Germanic or Celtic customs has continued unabated since 1945. For this reason, it can be assumed that for several centuries there were no festivals similar to Shrovetide, but rather that these arose in the high and late Middle Ages with Lent.

Medieval

In medieval Europe, from the 12th century to the end of the 16th century, "Feasts of Fools" were celebrated around Epiphany Day, January 6. Although such festivals also took place in churches, they were not ecclesiastical festivals. In these, the lower clergy temporarily assumed the rank and privileges of the higher clergy. Church rituals were parodied. Even a "pope" was elected; on December 28, the day of innocent children, a child bishop was often chosen. The inhabitants of the towns were also involved in the festivities in the form of processions. Fools' or donkey fairs were also widespread during the actual carnival days.

The oldest known literary reference to the "fasnaht" is found in a part of the Parzival by the minnesinger Wolfram von Eschenbach, dated 1206. There it says that "die koufwip zu Tolenstein an der fasnaht nie baz gestriten" Wolfram von Eschenbach describes there in flowery words how the women around the castle of the Counts of Hirschberg-Dollnstein performed grotesque games, dances and disguises on the Thursday before Ash Wednesday. The small market town of Dollnstein in the Altmühltal (Bavaria) therefore claims to be the cradle of German carnival in general and of Weiberfastnacht in particular.

One of the earliest mentions of Shrovetide can be found in Christoph Lehmann's Speyer Chronicle of 1612, which reports from old records: "In the year 1296, the mischief of Shrovetide was started somewhat early / in which some burghers carried off the worst of it in a fight with the clerical servants / after which the matter was brought before the council with difficulty / and they begged for punishment for the wrongdoers". (Clerisey Gesind means the servants of the bishop and the cathedral chapter, i.e. the clergy, in the cathedral immunity). The council forced the cathedral provost to hand over the clerical Gesind for punishment. For the cathedral chapter these encroachments were cause for a complaint against the council and citizens of the city, and excommunication was threatened. Due to the determined reaction of the city, however, the matter came to nothing.

On March 5, 1341, the word "Fastelovend" is mentioned in the so-called oath book of the city of Cologne with the remark that the council was no longer allowed to grant money for it - despite the earlier customary grant payment to the "Richerzeche", that group of wealthy citizens who were later called patricians: "But the council shall not grant grants from the city's assets to any society on Shrovetide." On October 26, 1353, it was made clear that Archbishop William of Gennep forbade the clergy and religious to sell or serve beer and wine; this proved that there was obviously a great interest in alcoholic beverages at Carnival. In June 1369 the ban was lifted again as part of a compromise. On July 1, 1412, a ban by the Cologne Council on holding games and dances in secret places and guild houses without the knowledge and will of the guilds came into force. In 1422 the peasant of Cologne is mentioned for the first time in a poem as the shield-holder of the realm. In 1425 the peasant then also appears for the first time in a Rose Monday procession. Around 1440, illustrations of the carnival were created in a frieze of the Gürzenich.

The Cologne City Council repeatedly banned the "Mummenschanz", for example in 1487 the "Vermomben, Verstuppen und Vermachen" and in the 17th century several times "die Mummerey und Heidnische Tobung", probably because of excesses that were difficult to control. In 1570 the Cologne virgin also appeared next to the peasant for the first time. She embodied the city founder Agrippina and the free independent city.

The medieval Fastnacht is traced back to the Augustinian teachings in his work De civitate Dei. Shrovetide therefore stands for the civitas diaboli, the state of the devil. Therefore, Shrovetide, which often got out of hand, was tolerated by the Church as a didactic example to show that the civitas diaboli, like man, is transient and that in the end God remains victorious. With Ash Wednesday, therefore, Shrovetide had to end in order to illustrate the inevitable conversion to God. While the church remained inactive in the case of blasphemous scenes during Shrovetide, the continuation of Shrovetide celebrations into Ash Wednesday was strictly prosecuted.

In the late 14th and 15th centuries in particular, Shrovetide was celebrated in the German region, for example the Nuremberg Schembartläufe. Around this time, the jester also found his way into Shrovetide, who, in the didactic sense of Shrovetide, was supposed to point out transience.

In some carnivals - especially in Tyrol - against this background the mask is already taken off at six o'clock on Shrove Tuesday evening for the "Betzeitläuten". The background is not clear. Already Caesar wrote about the custom of the Celts to let the new day begin with nightfall, just as the new year began with the onset of winter (compare Halloween). On the other hand, the beginning of the day with nightfall is also an element of Jewish and early Christian tradition.

On 9 February 1609, the carnival festival and the "Mummerei" were once again banned in Cologne in order to maintain public order. In addition to the usual drumming and trumpeting, it often degenerated into excess - also by wearers of clerical clothing. In 1610, the craftsmen were allowed to go on their mummery dance again, and in 1640 the people and the lower clergy even elected "bishops of fools". On 7 February 1657, the council once again banned the "Mummerei" during the carnival period. In 1660 an inner-city protection force was established, called the Funken. This was probably the birth of the Cologne Funken. Despite the ban on mummery, a city soldier was stabbed to death by carnivalists in 1699.

Modern Times

The Reformation called the pre-Easter Lent into question. Shrovetide thus lost its meaning. In Protestant regions, many customs fell into oblivion again. In the Baroque and Rococo periods, carnival festivities were celebrated, especially in castles and at the courts of princes, with masks that borrowed heavily from the Italian commedia dell'arte.

In February 1729, on the Thursday before Carnival, the nuns in the Cologne convent of St. Mauritius danced and jumped through the halls in secular disguise. That was probably the first Women's Carnival. In 1733 the Jesuits wanted to overcome the excesses at carnival time by special carnival games. On 7 February 1779, masquerades and mummery were again banned in Cologne, but this time because of the danger of war as a potential source of danger.

While in the cities more and more craft guilds and there especially the young journeymen organized the carnival, in the early 19th century, especially in the Rhineland area, the bourgeoisie took over the festive event, as guilds lost importance or were even dissolved in the wake of the French Revolution and the invasion of French troops under Napoleon Bonaparte. The French occupiers banned carnival in Cologne on 12 February 1795, but allowed it again on 7 Pluviôse of the year XII. (28 January 1804) again. In 1804 carnival was again permitted, but was regarded as boorish and often deplored. It was at this time - probably not for the first time - that the call "Kölle Alaaf" appeared, as a toast call for the later King Frederick William IV of Prussia during his visit to Cologne in 1804. The king, who was friendly to Cologne, later recalled it during his revisit in 1848 on the occasion of the start of further construction on Cologne Cathedral and also called out "Alaaf" at the end of his speech.

The bourgeoisie still celebrated foolish masked balls, but the street carnival was almost extinct. Carnival in Cologne, which had been Prussian since 1815 after the withdrawal of the French, was revived and reorganized in 1823 with the founding of the "Festordnenden Comite", which added the component of criticism of the (foreign) authorities: a "cultural-political prank with a humorous ambience".

Especially in Austria, Switzerland, Alsace, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg older forms were preserved. Especially in Baden-Württemberg, a distinction is made today between carnival and Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht. After the carnival had also established itself here towards the end of the 19th century, a return to the old forms was demanded after the First World War, which manifested itself in the founding of the Association of Swabian-Alemannic Fools' Guilds in 1924.

While older carnivals in southwestern Germany can still be found mainly in Catholic areas, a veritable carnival boom in the 1990s also introduced carnival in Protestant areas. In Switzerland, Basel has a special status: the city celebrates an old, traditional Fastnacht (Basler Fasnacht) despite the fact that Protestantism has prevailed for centuries. In Winterthur, too, the Winterthur Fasnacht was able to survive despite the Reformation and prohibition.

In other countries, Mardi Gras and Carnival could hardly establish themselves; in England, for example, many customs fell into oblivion due to Henry VIII's Reformation, which therefore could not consolidate in the United States and Canada either. One of the few exceptions here is Quebec and the formerly French and Catholic New Orleans.

The carnival of Acireale near Catania is the oldest in Sicily

"Carnival of Međimurje", Northern Croatia (2011)

Street carnival in a Catholic village in the eastern Netherlands

Street Carnival 1932

Carnival procession in Lucerne

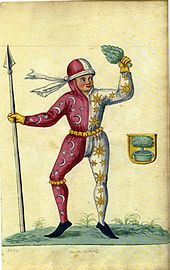

A Nuremberg Schembart Runner (1472)

Timing of the carnival

See also: Carnival season

Start

As beginning of the Fastnachtszeit was considered and/or is valid in many German-speaking countries originally Dreikönigstag, 6 January.

Since the 19th century, the official opening of the carnival season has also taken place in many regions on 11 November, the "Eleventh in the Eleventh", starting at 11:11 am. The background to this is that even before Christmas, shortly after the festival was fixed in 354, there was a preparatory forty-day fasting period, similar to the Easter fasting period after carnival. It began on November 11, St. Martin's Day. It was to consume available foods that were not "fit for Lent," such as meat, fat, lard, eggs, and dairy products. St. Martin's Day was also the end of the farming year, when the rent was due and the servants changed.

However, the period from 12 November to 5 January remains largely carnival-free even in the centres of carnival along the Rhine, which is explained by the aforementioned pre-Christmas Lent, the role of November as a month of mourning and the contemplative nature of Advent. As far as one speaks of an "advance" of the beginning of carnival or of a "season opening" on November 11, this is therefore at least misleading. From its history of origin, the 11th of November rather represents a second, "small" carnival.

However, especially in the surrounding areas, more and more meetings are held during this time - even before 11 November - because then most of the performing artists are cheaper than in the main season, when they have many performances in one evening. In January, the foolish season begins, especially in the strongholds, with the presentation of the new regents, the Prince Proclamation.

Highlight

Fastnacht reaches its climax in the actual Fastnacht week from Schmotzigen Donnerstag (from Schmotz = lard, which refers to Fastnachtsküchle baked in lard) in the Swabian-Alemannic region or Weiberfastnacht in the Rhineland or Fetter Donnerstag (Fat Thursday) in the Harz region, in northern Thuringia and in southern Saxony-Anhalt via Nelkensamstag (Carnation Saturday), Tulpensonntag (Tulip Sunday), Rosenmontag (Rose Monday) to Fastnachtsdienstag (Shrove Tuesday), also known as Veilchendienstag (Violet Tuesday). On Rose Monday in particular, there are corresponding parades - although roses originally did not refer to the flower, but to the verb rasen.

The largest parades take place in the carnival centres of Cologne, Mainz and Düsseldorf. Measured by the number of participants, the parade in Eschweiler is also one of the largest in Germany. There are also annual parades in Aachen, Bonn, Duisburg, Dülken, Erkelenz, Euskirchen, Koblenz, Krefeld, Leverkusen, Meckenheim, Mönchengladbach, Rheinbach, Siegburg, Trier and many other places. But also further south, for example in Frankfurt on the Main, Wiesbaden, Aschaffenburg, Mannheim, Ludwigshafen on the Rhine, Obertiefenbach, Würzburg and Karlstadt there are in each case on the Fastnachtssonntag (in former times delivery of the Fastnachtshuhn) removals. These are called in the Rhineland "Zoch" (D'r Zoch kütt - "The train comes", in Bavaria "Gaudiwurm").

In Karlsruhe and Stuttgart there are large parades on Shrove Tuesday with several hundred thousand visitors. The largest parades in northern Germany are the traditional Schoduvel in Braunschweig on Shrove Sunday and the carnival parade in Berlin.

In the districts, towns and villages around these centres there are parades on Saturday (Carnival Saturday), Sunday (Orchid or Tulip Sunday) and Tuesday (Violet Tuesday). In the Duisburg district of Hamborn, the largest children's carnival procession in Europe has been held on Carnival Sunday for decades.

In Austria, most festive events and parades take place on what is known here as the Fasching weekend, i.e. on Fasching Saturday and Fasching Sunday.

End

Ash Wednesday marks the beginning of Lent. On the night of Ash Wednesday at midnight sharp, the carnival ends and there is a tradition in many places that the carnivalists burn a straw doll, the so-called Nubbel, on this night as the person responsible for all the vices of the carnival days. The transgressions or sins committed during the carnival period are placed on the Nubbel so that they can no longer apply after it is destroyed. In some areas (e.g. Cologne) this is accompanied by theatrical, artificial weeping. In Düsseldorf and the Lower Rhine towns such as Krefeld, Duisburg, Mönchengladbach, Kleve or Wesel, the so-called Hoppeditz is laid to rest. This was originally a typical Lower Rhine jester figure. This rogue or Hanswurst had similarities with Till Eulenspiegel and the medieval court jesters. It is reported that in the 18th and 19th centuries it was the custom in the Lower Rhine area of the little people to walk through the streets on Ash Wednesday night equipped with poles on which sausages were hanging and to sing funny songs.

In some places the carnivalists meet again on Ash Wednesday for a joint fish supper, for a ritual "purse-washing" or even just now for an internal Nubbel burn.

Carnival date

The end of the carnival is Ash Wednesday. Its date depends directly on the location of Easter: In 325, the Council of Nicaea set the date of Easter for the first Sunday after the spring full moon. Around 600, Pope Gregory the Great established a 40-day period of Lent before Easter to commemorate the time Jesus Christ spent in the wilderness (Matt 4:1-2 EU). According to this regulation, Lent began on the Tuesday after the 6th Sunday before Easter (Invocavit or Dominica prima Quadragesimae, 1st Sunday of Lent, in German also Funkensonntag).

At the Synod of Benevento in 1091, the six Sundays before Easter were exempted from fasting. In order to still have a 40-day Lent, the beginning of Lent was moved forward by six days to today's Ash Wednesday, the Wednesday after the 7th Sunday before Easter. The length of a carnival season is thus dependent on the movable date of Easter and is calculated according to the Easter formula. According to this, Ash Wednesday is on the 46th day before Easter Sunday. The earliest possible Ash Wednesday date is February 4, and the latest possible is March 10. Thus there are very short and very long sessions.

Deviating Shrovetide dates

In some regions, both carnival dates, the old Burefasnacht (farmers' carnival, before Tuesday after Invocavit) and the new gentlemen's or priests' carnival (before Ash Wednesday) still existed side by side until the 16th century. Especially in Baden and in Switzerland many customs of the old Fasnacht and the old date have been preserved. The best known is the Basel Fasnacht.

This begins on the Monday after Ash Wednesday at 4:00 am with the Morgestraich and ends on the following Thursday morning, also at 4:00 am. Here the Guggenmusik plays a role. This context also explains that the date of the Protestant Basel Fasnacht - as often written - does not refer at all to the Reformation, but to the old date of the Fastnacht. In Basel the carnival was never permanently abolished during the Reformation. In the German exclave of Büsingen, the Peasants' Carnival is celebrated with a parade on the Sunday after Ash Wednesday.

In the Orthodox Churches, the full fast begins on the Monday after the 7th Sunday before Easter, and the abstinence from meat begins a week earlier. The Russian butter week, in which traditional celebrations are held and large quantities of bliny are eaten, lies in between. Other Eastern European countries have similar customs. Since the eastern Easter is often later than the western one - based on the western reform of the calendar - Shrovetide is also postponed.

In Hollabrunn (Lower Austria), due to a vow made by the citizens in 1679 (renewed in 1803) and because the municipality was spared from the plague, there has been no celebration from Carnival Sunday to Carnival Tuesday since then.

The Groppenfasnacht in Ermatingen on Lake Constance in Switzerland (Canton Thurgau) is known as the "world's latest carnival", as it does not take place until Laetare, the Sunday before Lent. It is the most traditional carnival in eastern Switzerland. The "Groppenumzug" as the highlight only takes place every three years.

Appointment overview

| Year | Weiberfastnacht | Carnival Sunday | Rose Monday | Rose Monday (Orthodox) | Ash Wednesday | Start of carnival (Basel) |

| 2013 | February 7 | February 10 | February 11 | March 18 | February 13 | February 18 |

| 2014 | February 27 | March 2 | March 3 | March 3 | March 5 | March 10 |

| 2015 | February 12 | February 15 | February 16 | February 23 | February 18 | February 23 |

| 2016 | February 4 | February 7 | February 8 | March 14 | February 10 | February 15 |

| 2017 | February 23 | February 26 | February 27 | February 27 | March 1 | March 6 |

| 2018 | February 8 | February 11 | February 12 | February 19 | February 14 | February 19 |

| 2019 | February 28 | March 3 | March 4 | March 11 | March 6 | March 11 |

| 2020 | February 20 | February 23 | February 24 | March 2 | February 26 | March 2 |

| 2021 | February 11 | February 14 | February 15 | March 18 | February 17 | February 22 |

Cortège, the carnival procession in Basel

Mardi Gras Burning

Monument for guardsmen in Mainz

Carnival fountain in Mainz

Rhenish carnival parade in Koblenz

Questions and Answers

Q: What is Carnival?

A: Carnival is a public festival that takes place in many cities and towns around the world.

Q: When does Carnival usually take place?

A: Carnival usually takes place in February or March each year.

Q: How long can Carnival last for?

A: Carnival can sometimes last for several weeks, but in some places, it can be just one day of celebration.

Q: What are some common events at Carnival?

A: Some common events at Carnival include street parades, bands, costumes, and many people wearing masks.

Q: What is the religious connection to Carnival?

A: Carnival is linked to religious traditions in the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches.

Q: What else is Carnival linked to besides religious traditions?

A: Carnival is also linked to local customs.

Q: Which locations celebrate Carnival?

A: Many cities and towns in many countries around the world celebrate Carnival.

Search within the encyclopedia