Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

![]()

Reanimation is a redirect to this article. For the album by the band Linkin Park, see Reanimation (album).

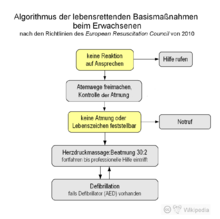

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation is intended to end respiratory and circulatory arrest and thus avert the imminent death of the victim. Other names for this are resuscitation, resuscitation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). In the event of circulatory arrest, it is essential to act quickly: After only about three minutes, the brain is no longer supplied with sufficient oxygen, so that irreversible damage can occur there.

With cardiac massage, the residual oxygen in the blood can be circulated and thus the probability of survival can be decisively increased until the arrival of the rescue service or specialist help. Even without first aid knowledge, it is possible for the medical layperson to save or at least prolong life by means of basic life support. He or she should check whether the unconscious person is still breathing normally, call the emergency services using the emergency number 112, which is valid throughout Europe, and, in the case of adults, firmly press the sternum in the middle of the chest about five centimetres 100 to 120 times per minute and then completely relieve the pressure again and do not stop until help arrives. Ventilation is not the most important measure for people with sudden cardiovascular arrest. Cardiac massage is central. If possible, it should be supplemented by ventilation (e.g. mouth-to-mouth ventilation). The following rhythm is recommended: press 30 times and then ventilate twice.

If available in the vicinity, an automated external defibrillator (AED) can also be used. Advanced life support requires specially trained personnel with the appropriate equipment and is performed by ambulance personnel, an emergency physician, or hospital medical staff. These include the administration of medication, intubation, professional defibrillation and external (transcutaneous) pacemakers. Nevertheless, the prognosis of resuscitated patients is poor, with a longer-term survival rate (time of hospital discharge) of between two and seven percent.

This article is based on the resuscitation guidelines of the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) from 2015 (Current version: March 2021). The practical implementation differs in different countries, medical institutions and aid organisations.

Resuscitation training on a dummy

Causes and forms of circulatory arrest

→ Main article: Circulatory arrest

The most frequent cause of circulatory arrest in western industrial nations is sudden cardiac death, at over 80 %, caused by heart attack or cardiac arrhythmia. In Germany, 80,000 to 100,000 people die each year from sudden cardiac death, which corresponds to 250 cases per day. Other internal diseases such as lung diseases (e.g. pulmonary embolism), diseases of the brain (e.g. stroke) and others account for about 9 %. In another 9%, external causes such as accidents, suffocation, poisoning, drowning, suicide or electrocution are the cause of circulatory arrest.

The distinction between hyperdynamic (defibrillatable, electrically active, hypersystolic) and hypodynamic (non-defibrillatable, electrically inactive, asystolic) circulatory arrest is particularly important for measures of advanced therapy. In the hyperdynamic form, which is present in about 25% of cases when the patient is found, the muscle and excitation conduction system of the heart show activity, but it is disorganized. There is no longer coordinated cardiac work and thus no substantial ejection of blood into the circulation. Pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT), ventricular flutter and ventricular fibrillation (VF) are possible causes of this type of circulatory arrest. After a few minutes, it inevitably changes to the hypodynamic form, in which no electrical activity is detectable and which is known as asystole. A special form is electromechanical decoupling (EMD) or pulseless electrical activity (PEA), in which ordered electrical activity is observed, but this no longer causes ejection in the form of a pulse wave.

Data on the incidence of resuscitation for circulatory arrest are incomplete. The annual incidence of resuscitation for out-of-hospital circulatory arrest with a cardiac cause ranged from 50 to 66 per 100,000 population in a Scottish study. The rate of in-hospital cases varied from 150 (Norway) to 350 (England) per 100,000 patients admitted.

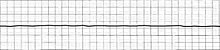

ECG lead from ventricular fibrillation

ECG derivation of an asystole

Basic measures of resuscitation

The basic measures that can be applied without additional aids, also referred to as basic life support (BLS) in international terminology, serve to maintain a minimal circulation in the patient's body by means of cardiac massage and the supply of sufficiently oxygenated blood by mouth-to-mouth resuscitation or mouth-to-nose resuscitation (see respiratory donation) until normal blood circulation is restored or to bridge the time until extended therapeutic measures can be applied without irreversibly damaging the patient's vital organs. This applies above all to the brain, which is damaged by a lack of oxygen after only a few minutes. The blood flow that can be achieved by the basic measures corresponds at best to about one third of the healthy circulation. The basic measures can be performed by one or two rescuers. The ratio of cardiac massage to ventilation is independent of this.

As a rule of thumb, an ABC scheme (ABC basic measures, ABC of first aid) of life-saving immediate measures was developed:

- A (clear airways and keep them clear)

- B (ventilation or respiration)

- C (circulation, especially by cardiac massage).

The basic measures (also in the context of first aid) can be divided into three simple steps today:

- Check: Check if the unconscious person responds (e.g., by shaking the shoulder), Check breathing: No breathing or no normal breathing (e.g., gasping, rattling)?

- Calling: Call for help - involve bystanders and make or arrange for an emergency call to be made.

- Squeeze: Press firmly and quickly (100 to 120 times per minute) into the center of the chest (e.g., to the beat of Stayin' Alive by the Bee Gees).

If possible, mouth-to-mouth or mouth-to-nose resuscitation should be performed: press 30 times and then ventilate twice. With cardiac massage, the residual oxygen in the blood can circulate and supply the brain with oxygen. Until rescue service personnel take over, the probability of survival can be decisively increased in this way. Because after only three minutes the brain is no longer sufficiently supplied with oxygen - irreversible damage occurs.

Semi-automatic defibrillators (automated external defibrillators, AEDs) designed specifically for use by first responders are also increasingly available at central locations in public buildings. These guide the untrained user through defibrillation with voice instructions and sometimes also give instructions on how to perform chest compressions and ventilation. Automated defibrillation, originally an advanced measure of professional helpers, is thus now counted among the basic measures of resuscitation. However, the use of AEDs must not delay or replace chest compressions.

The basic measures for the first aider also include immediately calling the emergency services. The emergency services carry out the basic measures in the same way, but technical aids such as a defibrillator are available. In addition, extended measures are used to secure the airways and thus ensure ventilation. Oxygen can be provided to the patient in high concentrations, for example by means of a resuscitation bag or a ventilator via an endotracheal or laryngeal tube. The same applies to resuscitations in medical facilities, which are often performed by "resuscitation teams".

Anyone who finds a motionless person is obliged to immediately start life-saving measures to the best of his or her knowledge, as otherwise he or she may be guilty of failure to render assistance in Germany. Exceptions are bodies that already show clear signs of death such as strong signs of decomposition or injuries that are incompatible with life. Once started, cardiopulmonary resuscitation is to be continued without interruption until help is received (not just until "arrival"!); a doctor decides whether to discontinue the measures on the basis of certain criteria (for example, age, duration of circulatory arrest, prognosis of the underlying disorder). This does not apply to the non-initiation or interruption of measures in the event of danger to the patient, e.g. due to health problems.

Recognition of circulatory arrest, clearing the airways

| | |

| occluded airways | clear airways |

| Airway on the head section model of an adult, left before, right after hyperextension of the neck | |

In order to detect circulatory arrest, the patient's vital functions of consciousness and breathing are checked (also referred to as diagnostic block). A check of the circulatory activity is not necessary for lay rescuers, as there is usually no circulation in the case of respiratory arrest and the check cannot be carried out safely by an untrained person. Taking care of his own safety, the rescuer checks the patient's reaction by addressing him and shaking his shoulder. In some cases a pinch in the arm or similar is more suitable than shaking the shoulder, so that no possible damage to the spine etc. is aggravated.

When the patient's head is in a neutral position, the tongue falls back into the throat and obstructs the airway. In order to check the patient's breathing or to enable ventilation, the head or neck must therefore be hyperextended (life-saving manoeuvre). In order to protect the possibly injured (cervical) spine, this should be done by moving the chin and forehead, but not by reaching into the neck. In addition to the life-saving handgrip, the Esmarch handgrip can also be used, in which the lower jaw, which has fallen backwards, is pulled forward. This may allow the patient to breathe on his or her own again.

The breathing activity is then checked for a maximum of 10 seconds by listening to the breathing sound, feeling the exhaled air on the patient's own cheek and observing the breathing movements of the chest. If the patient's breathing is not "normal", the first aider begins with the basic resuscitation measures. In lay resuscitation, it is common for gasping breaths to be mistakenly perceived as a non-threatening condition. Gasping is recognizable by slow, irregular, often noisy breaths, and the head, mouth, and larynx often move in an unnatural manner.

A person with gasping breaths must be resuscitated.

A patient who is breathing normally is placed in the recovery position, while breathing continues to be monitored so that any respiratory arrest or transition to gasping can be detected at an early stage and resuscitation can begin. If there is a suspicion that foreign bodies (leftovers, dentures, chewing gum, etc.) are obstructing the airway, resuscitation is started on the unconscious patient without delaying the removal of the foreign body by prolonged attempts. Some chest compressions during resuscitation may then result in removal of the foreign body from the airway. Removable dentures are removed beforehand if possible.

If a patient with foreign bodies in the respiratory tract is still conscious, an attempt is made to remove them first by forceful blows between the shoulder blades inducing coughing and then by repeated pressure on the upper abdomen (Heimlich manoeuvre). The Heimlich manoeuvre has been discouraged on several occasions because of the risk of injury to the liver and spleen, but it is the method of choice in cases of acute danger of suffocation.

Medical personnel perform the vital signs check with more detailed measures. Before checking breathing, the oral cavity is also inspected for the presence of foreign bodies or vomit. These are removed if necessary. This may be done using the fingers, a suction pump, or Magill forceps. During the respiratory check, a circulation check may also be performed, provided that the assessment time does not exceed 10 seconds. In addition to observing general vital signs (movement, breathing, or coughing), trained personnel will also palpate the carotid or femoral pulse. However, this can be difficult even for experienced personnel. When an ECG/defibrillator device arrives, the heart rhythm is analyzed electrocardiographically. The measures to be initiated do not differ significantly from those performed by laypersons.

Cardiac massage

During (external or extrathoracic) chest compressions (repeated chest compressions), the heart is forced towards the spine by applying pressure to the sternum. This increases the pressure in the chest and blood is ejected from the heart into the circulation. In the subsequent relief phase, the heart fills with blood again. Both compression of the heart by externally applied pressure and pressure fluctuations inside the chest caused by this ("thoracic pump mechanism") have been considered to be the cause of the effect of chest compressions. It is important to minimize interruptions ("no-flow time") during chest compressions.

As a preparatory measure, the patient is placed flat on his back on a hard surface such as the floor or a resuscitation board and his chest is cleared. The pressure point is located in the middle of the chest on the sternum.

For adults: the sternum is pressed down briefly and forcefully 30 times in succession, followed by 2 breaths. The indentation depth is about five to six centimetres. Between two pumping strokes, the chest should be unloaded again so that the heart can fill sufficiently with blood. The target frequency of cardiac massage is at least 100 and at most 120 compressions per minute. The correct posture makes the work easier for the rescuer. The rescuer kneels upright next to the patient, with his shoulders vertically above the patient's sternum. The caregiver presses rhythmically with the weight of his upper body, while his arms are extended and his elbows are pushed through. Since the 1990s, devices with frequency- and strength-controlled pistons have also been increasingly used as mechanical resuscitation aids for cardiac massage. In infants and young children, the depth of compression is about one-third of the depth of the chest and only the fingertips are used for compression (for more information, see #Special features of neonates, infants, and children). If more than one rescuer is available, chest compressions and ventilation can be divided between two people.

During cardiac massage, rib fractures often occur, even when performed correctly. These are to be accepted as a side effect and do not pose any further danger to the patient. Therefore, even after one or more rib fractures, chest compressions should be continued after checking the technique used.

Ventilation

→ Main article: Ventilation - by rescuers and doctors

→ Main article: Breath donation - by emergency responders

Ventilation without further aids is performed as mouth-to-nose or mouth-to-mouth ventilation (see respiratory donation). The neck of the patient is hyperextended. The nose must be closed for mouth-to-mouth ventilation, the mouth for mouth-to-nose ventilation. The volume is correctly selected when the chest rises visibly. The ventilation phase should last about one second; ventilation is repeated (as long as both cannot take place in parallel or uninterruptedly, as after intubation of the trachea, alternating with cardiac massage and a ratio of ventilation to chest compression of 2:30) until the ventilated person is breathing on his own again. To improve hygiene and overcome any disgust that may be present, there are various ventilation aids such as ventilation films with a filter and various types of pocket masks, although their use requires practice. If poisoning with contact poisons (for example, pesticides such as parathion) is suspected, respiratory donation should be avoided. If a rescuer is not confident in giving breaths, continuous chest compressions are an acceptable alternative for that rescuer.

Suitably equipped and trained rescuers use a breathing bag with face mask for ventilation, often in conjunction with a Guedel tube, Laryngeal tube or after (endotracheal) intubation. The breathing air can be additionally enriched with oxygen, whereby concentrations of almost 100% can be achieved through appropriate oxygen flow setting (maximum flow) and use of an oxygen reservoir.

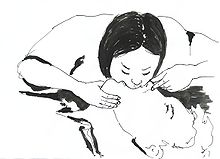

Mouth-to-Mouth

Correct posture for chest compressions. Elbows extended, shoulders vertically above hands.

Recognition of circulatory arrest and implementation of basic measures

Carrying out basic measures on a model, with a defibrillator in the background

Questions and Answers

Q: What is CPR?

A: CPR stands for Cardiopulmonary resuscitation which is a set of actions that should be done if a person stops breathing, or if their heart stops.

Q: What is the goal of CPR?

A: The goal of CPR is to force blood and oxygen to keep flowing through the body.

Q: Can CPR start a person's heart again?

A: No, CPR cannot start a person's heart again. However, it can keep pushing blood and oxygen around the body long enough that sometimes, it can keep the body from getting damaged by not having enough oxygen.

Q: Why do people need CPR?

A: Every part of the body needs blood and oxygen to survive. So, in case of the stoppage of breathing or heart, CPR is needed to force blood and oxygen to keep flowing through the body.

Q: Can regular people perform CPR?

A: Yes, regular people who are not medical professionals can perform CPR by realizing that a person is not breathing or has suddenly collapsed, calling 911 (or whatever the emergency telephone number in their country is) and doing chest compressions until help arrives.

Q: What actions can many medical professionals do during CPR?

A: Many medical professionals can also perform CPR by doing chest compressions, giving rescue breaths, and using an AED (Automated External Defibrillator) to shock the heart.

Q: How can chest compressions be done during CPR?

A: During CPR, chest compressions can be done by pressing hard and fast in the middle of the chest, on the breastbone, until help comes, and this will force blood to keep flowing to the body.

Search within the encyclopedia