C

![]()

This article is about the Latin letter C. For other meanings, see C (disambiguation).

For technical reasons, C# is redirected here; for the C# programming language, see C-Sharp.

Cc

C or c (pronounced: [t͡seː]) is the third letter of the classical and modern Latin alphabet. It initially denoted the velar closure sounds /k/ and /g/ (the latter represented since the 3rd century BC by the newly created G); as a result of the assibilization before front-tongue vowel attested since Late Latin, c also denotes a (post-)alveolar affricate in most Romance and still many other languages (Ital. [ʧ], dt, Polish, Czech [ʦ]) or a dental or alveolar fricative (English, French [s], Spanish [θ/s̺]). The letter C has an average frequency of 3.06% in German-language texts.

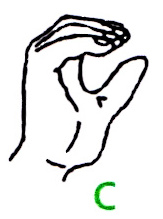

The finger alphabet for the deaf or hard of hearing represents the letter C by forming an open semicircle with the thumb and remaining fingers.

Letter C in the finger alphabet

Pronunciation

In most Romance languages, as well as in the medieval and modern pronunciation of Latin and numerous words borrowed from it, c before consonants and back vowels (including /a/) stands for the voiceless velar plosive /k/, before original front-tongue vowels e, i (also before Latin ae, oe, y) for a sibilant (depending on language and language stage, an affricate /ʧ/, /ʦ/ or pure fricative /ʧ/, /ʦ/ or /ʦ/). ae, oe, y), on the other hand, for a sibilant (an affricate /ʧ/, /ʦ/ or a pure fricative /s/, /ʃ/, /θ/, depending on language and language stage; cf. Romance palatalization). The distribution of these allophones after subsequent vowel is occasionally rendered in language-specific phonetic transcription by the series ka - ce/ze - ci/zi - ko - ku (so-called ka-ze-zi-ko-ku rule) or summarized a mnemonic of the following kind: "Before a, o, u pronounce c like k, before e and i pronounce c like z." Where such a sibilant is placed before a back consonant such as /a/, /o/, /u/ (or a front-tongue vowel that developed from it only later, such as French [y] < Latin /u/), it is often denoted by ç, z, or (in Italian) the digraph ci. Conversely, for the velar before front vowel k, in French regularly qu, in Italian ch occurs. In addition, the letter c is sometimes also generally replaced by z or k, e.g. in modern German for Latin loanwords: Zirkus instead of Circus.

Outside Italian, the digraph ch also stands for a sibilant in many Romance languages, and for a velar or palatal fricative in German and Gaelic. In German, the combination ck often serves as a variant of k to indicate that the preceding vowel is pronounced short; however, a ck is sometimes found after long vowels in North German place and family names (e.g. Mecklenburg (ˈmeː-), Buddenbroock); the trigraph sch represents the sound [ʃ] (as in school).

Origin

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Foot (protosinaitic) | Phoenician gimel | Variant of the early Greek gamma | Greek gamma | Etruscan C | Latin C |

The original form of the letter, which comes from the Proto-Sinaitic script, represents a foot. In the Phoenician alphabet this meaning was retained. The letter received the name Gimel (camel) and had the sound value [g]. The Greeks adopted the letter as gamma. In the beginning, gamma was written in a form that looked like a roof (similar to the later lambda). By classical times, gamma had evolved into Γ. Probably responsible for this, besides the change of the writing direction from right-to-left to left-to-right, was the necessary change of writing tools for describing organic matter.

When the Etruscans adopted the early Greek alphabet, they had no use for the gamma, since Etruscan did not have voiced closure sounds like [g]. However, the Etruscan language had three k sounds. The Etruscans therefore changed the phonetic value of the letter to reflect the voiceless closure sound [k] before [e] or [i].

With just this phonetic value, the sign C then migrated into the Latin alphabet and was used by the Romans, who definitely distinguished between the tenuis K and the media G, so originally for the sounds [g] and [k], more precisely, for the syllables [ge]; [gi] and [ke]; [ki]. Even if in archaic times in Latin writing practice three [k]-sounds, differently colored from their subsequent sounds, were not yet consistently distinguished sign-wise, a differentiation did set in, namely C before [e], [i], K before [a] and liquids, Q before [o], [u], the former of which is still responsible for our present-day G.

Already in the 4th century BC this process came to an end by placing the letter Q only before the consonantal [u], while the letter K occurred from the 3rd century BC only in formulaic abbreviations, such as Kal. = Kalendae and the brand K. = Kalumniator. Both letters were displaced in favor of the C.

Now, however, also the [g]-sound was attached to the sign C and according to Plutarch (Quest. Rom. 54) it was the writing school operator Spurius Carvilius Ruga in 230 BC who, by adding a dash, took the G out of the C and shifted it to the place which the [ts]-sound, i.e. the Greek zeta, our zett, occupied in Greek. The character C as a [ge]-sound was preserved only in the abbreviations C. ≙ Gaius and CN. ≙ Gnaeus.

It is interesting to note that the Roman did not place the new letter, i.e. the linking of the sign C with cauda (tail) = G with the sound [g], at the end of the alphabet, as was done later with the Greek Y and Z, but in the place that was assigned to the zett according to the Greek alphabet. After the voiced [z] sound, which stood in the zeta place in the alphabet, i.e. in the 7th place and was represented by the sign 'I', had become R (fesiae → feriae), the sign was no longer necessary and the letter was erased by the censor Appius Claudius Caecus in 312 BC (Marc. Capella: 1,3). Moreover, Greece had not yet been conquered and Greek scholarship was not yet native to Rome. This could be an indication that a gap was felt there, because also in Rome the letters still had the old Phoenician numerical meaning.

In Late Latin from the 5th century AD, the [k] before a light vowel became [ts]. This pronunciation became the standard in medieval Latin; it is the reason why the C has different phonetic values today. In Romance languages, this development was continued to some extent; the C there also has the phonetic values [tʃ], [s] or [θ].

Search within the encyclopedia