Byzantine art

![]()

This article or section is still missing the following important information:

ceramics, painting, mosaic (Ravenna!) etc. not treated

Help Wikipedia by researching and adding them.

Byzantine art is specifically the art of the Byzantine Empire, which existed from the 4th century to the 15th century. However, it also includes the art of the Byzantine-influenced neighboring countries of the former empire in the Middle East, the Caucasus, the Balkans, and the countries around the Caspian Sea and Russia. Thus it outlasted the fall of Constantinople. However, she also influenced the art of Latin Europe, especially the early architecture of the Carolingians and Ottonians and the church architecture of the upper Rhineland, as well as the panel painting of the High and Late Middle Ages in Italy, as well as the Marian painting of the Late Gothic and Early Renaissance of Northwestern Europe. It is known for its works of sacred architecture, enamel, textile, ivory and goldsmith art and is particularly associated with miniature, book, mosaic and icon painting.

The coverage of Byzantine archaeology or art history by the scientific disciplines is not entirely uniform. It is often (co-)treated by the chairs of Christian archaeology. In general, the history of the Byzantine Empire is often treated stepmotherly in Germany.

Detail of Angel at the Tomb of Christ (ca. 1235) Fresco in Mileševa (Serbia)

Detail from Dormition of the Mother of Mary (ca. 1265) fresco in Sopoćani (Serbia), the main work of late Byzantine fresco painting.

Drawing of the lost monumental statue of the Augustaion in Constantinople with the representation of Emperor Justinian (Justinian's Column), drawing by Nymphirios, Budapest University Library (Ms. 35, fol. 144 v.)

Emperor Justinian I or Anastasios I, so-called Barberini diptych, ivory carving (Paris, Louvre)

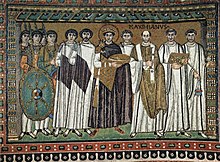

Emperor Justinian I, mosaic in the church of San Vitale in Ravenna

Pantokrator mosaic in the Chora church in Constantinople

.jpg)

Hagia Sophia, main church of the Christians in the Byzantine Empire (Istanbul)

Painting

In Byzantine art, painting, as fresco or panel painting, plays a prominent role and the icon thus represents the emblem of Byzantine art. At the same time, pictorial representations were tied to the theological mediation of the Christianity of the faithful. The veneration of images in Christianity is almost as old as the religion itself. The first statements on the image were made in the 4th century, when Christianity rose to become the state religion of the Roman Empire. Here there seems to have been a need for representation for the first time. In the 6th century the time of image veneration began in Christianity as a predominant and ecclesiastically approved custom.

Initially, the ideal conception of the iconographically formed figure in the religious sphere was the true face of Christ on the "sweat cloth of Veronica", which was created as a symbol of the truth of the original image. This Vera Icon (from Latin: vera = true and Greek: εικόνα = image, i.e. "true image") is so called because, according to tradition, it was not created by man but given by God. These archetypes of absolute beauty, as ideal forms of portraiture, influenced the artistic world. The cult history of the icon began with these miraculous images, which seem to be capable of supernatural favours. Thus, in early Christianity, it was desirable for images to explain themselves by performing miracles. At the same time, this opens up a scope for an artistic examination of the concept of the non-man-made image.

Through the mediation of an immediate understanding between individuals and God without the involvement of third parties and without intellectual effort, a canon of images, such as representations of saints, was standardized, which became fundamental in a Byzantine Church.

Icons

see also main article Icon

The icon as a panel painting cannot be specifically separated from fresco painting and mosaic, since icons were generally not limited to a particular medium. An icon can therefore be executed as a panel painting, mosaic or fresco.

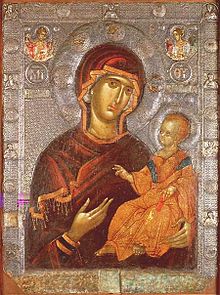

Icons gain immense importance from the 6th century onwards. Emperor Herakleios (reigned 610-641) attributed his accession to the throne to the help of an icon of the Virgin Mary, which he subsequently carried on his ship. The image of this icon was painted on the city gates in 626 for protection against the Avars. Also in private, especially representations of Mary with Child were widespread from the 7th century onwards. People lit incense and lamps before the icons, knelt before them, washed, dressed and kissed them.

More precise information on the distribution of icons executed as panel paintings in the early and middle Byzantine period is difficult to obtain. On the one hand, much was destroyed during the Iconoclasm (icon controversy), and on the other hand, the preservation situation of organic materials from this period (e.g. wood) is very poor. There are some preserved panel icons from this period (e.g. the icon of St. Peter from St. Catherine's Monastery), some of which differ stylistically from the late and post-Byzantine types.

Icons as special devotional images in the naos of the church between the bema and the altar have been described as early as the 8th century. Wooden icons placed between the columns in front of the altar are only common in the late Byzantine phase. Due to the need for devotional icons for the emerging iconostasis, the production of icons increases steadily between the 12th and 15th centuries.

In addition to the large-format icons, small-format private icons existed at the same time, which were made in and with valuable materials such as gold, silver, precious stones, ivory and cloisonné enamel. The materials were so precious that they were only produced in miniatures. Larger panel paintings rarely survive from the early period, and it is not until the 12th century and later that the number of large-scale wooden icons increases rapidly. In the 14th and 15th centuries, these not infrequently reach dimensions of over one metre.

Byzantine double icon (Constantinople, early 14th century) with St. Virgin Psychosostria. Ohrid, Icon Museum

Byzantine oil lamp for icon lighting

Byzantine double icon (Constantinople early 14th century) with the Annunciation. Ohrid, Icon Museum

Architecture

→ Main article: Byzantine architecture

Byzantine architecture is essentially a suspended architecture. Its vaults seem to be supported from above, without having any dead weight of their own. The columns are not seen as supporting elements, but as hanging roots or descending arms. The architectural conception of a building as something striving downwards is entirely consistent with the hierarchical way of thinking. There is no façade; all richness is concentrated in the spiritual core of the building. Most churches are cube-shaped on the outside, with a central dome or several domes, with the central one towering over the outer ones. The churches are plain. It is only in the Palaiological period (the late Byzantine era) that some variety is brought to the façade.

The periodization corresponds to the basic scheme of Byzantine art, which was measured in particular by the periods of greatest building activity and is significantly correlated with the economic conditions of the empire. As independent periods, the periods 375-600, 775-950, 1025-1200, and 1250-1400 can be connected with the dynastic situation. This confirms, also by statistical methods, the classical division of Early Byzantine architecture and the ages of the Macedonians, Comnenes, and Palaiologians and their overlaps especially between the architecture of the Macedonians and Comnenes, as well as the Comnenes and Palaiologians.

The early Byzantine architecture

Early Christian architecture forms an origin of Byzantine architecture. After the legalization of Christianity in 313 (by the Edict of Tolerance of Milan) and the change to the new capital Constantinople, the demand for representative buildings for the new religion increased by leaps and bounds, whereby pagan building types were adopted (basilica, central building).

The basilica, in ancient times a meeting room or market hall, became the main type of sacred architecture.

With the basilica as a sacred building in the early Middle Ages, the multi-aisle design and the illumination through the clerestory (high nave wall above the columns) were adopted. In the early period, the basilica was often unroofed, i.e. open to the roof truss at the top. The apse was usually located in the east. In it stood the bishop's throne, there were benches for the clergy, often also an altar and a lectern. As in the western early Christian basilicas, the narthex and an atrium were located in the west.

Characteristics of the central building were the centralized, mostly point-symmetrical, more rarely axially symmetrical ground plan, mostly covered with a dome.

From the (Roman, ancient) central building, the (Byzantine) central building with a cross ground plan developed through the expansion by means of side aisles. In the combination, the dome basilica and the cross-domed church emerged in the 5th century.

Important examples of these buildings can be found in Ravenna (San Vitale, Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Sant'Apollinare in Classe) as well as in Istanbul (the former Constantinople) and other places.

The Middle Byzantine architecture

The end of iconoclasm in 843 and the establishment of the Macedonian dynasty in 867 by Basileios I (867-886), an illiterate soldier who became a successful general and eventually ascended the Byzantine throne, marked the beginning of a rebirth of the Byzantine Empire.

The architecture of the Macedonians begins with the construction of the now destroyed Nea Ekklesia (Greek: Νέα Ἐκκλησία = "New Church" after conversion into a monastery later: "Nea Moni") under Basileios I. 876-880 as a new Hagia Sophia in the southeastern part of the Great Palace. The ground plan of the five-domed church of the Nea Ekklesia as a four-column building, the barrel cross supporting the dome is supported by four columns or pillars. This became stylistically influential for all Byzantine cross-domed churches of the time and spread to the Balkans and Russia. The Nea Ekklesia occupied a special position in the Byzantine court ceremonial until the 11th century. The valuable relics from the three crosses of the crucifixion of Jesus were brought from the treasury of the palace to the Nea and celebrated by the court and the emperor in an elaborate ceremony lasting several days. The Nea also acquired a special significance in this period due to the number of relics. Among other things, the relics of the sheep's coat of the Prophet Elijah, the table of Abraham, at which he is said to have conversed with three angels, the horn of Samuel, with which he is said to have anointed David, and the relics of Constantinethe Great were kept here. Pilgrims of the 12th century also reported that the staff of Moses and the cross of Constantine were displayed in the Nea. The oldest surviving example of Middle Byzantine sacred architecture in Constantinople is the Church of Constantine Lips, dedicated to the Virgin Mary. In almost all of these churches, the five-domed nave is supplemented by flank rooms.

While the most important monuments of early Byzantine art had been public buildings, the important monuments of this period were of a private character, that is, they were reserved for the dignitaries and court officials who had access to the palace. The social base of "imperial" art had been diminished. When the majority of ecclesiastical buildings became private, they gave way to monastic churches.

The monastery churches

Byzantine monastic churches are almost always cross-domed churches. They form with their corner rooms a square in which a Greek cross is inscribed. Mostly they are of modest dimensions. This was partly because the technical difficulties increase with size, and partly because the churches were usually built for numerically small orders. The dome rests on four arches, which are extended in the direction of the cross by four barrel vaults of equal length. The approximately square spaces between the arms fill the corners. The roofs of the spaces are kept lower so that the cross can be seen from outside. Four additional, smaller domes may step over the corner spaces between the arms of the cross or over the arms of the cross themselves, making a total of 5 domes crowning the church. The four-column type can be considered a sub-type of the cross-domed church: In the four-column church, the dome is supported by columns rather than pillars. That is why the church is usually smaller, higher and does not contain galleries. This eliminates the separation between the corner rooms and the main room. Another subtype is the ambulatory church. Here, the arms of the cross and the corner rooms form a gallery, which is often separated from the main room by triple arcades.

The late Byzantine architecture ("Palaiological Renaissance")

The architectural styles of the previous eras have been preserved: Cross-domed, four-post, and ambulatory churches. The dimensions became more modest and the exterior received novel, colourful accents through different layers of brick and house stone. The cross-domed church remained popular. One of the innovations was that churches were provided with a gallery on three sides. Churches were also rebuilt and decorations became more varied. The buildings became more irregular and the domes became larger.

The Palaiological Renaissance remains significant above all because of the internationalization of Byzantine art. It is no longer limited to the narrower area of the Byzantine Empire and its artistic centers in Constantinople, Thessaloniki and Mount Athos. By being passed on to the Slavic countries and the fact that these were often economically and politically more vital than the remnants of the late Byzantine Empire, Byzantine art also opened up to new impulses. The art of building, especially in Russia and Serbia, does indeed fall back on Byzantine models, but especially after 1375 it develops tendencies that noticeably bear a new signature in architecture and painting. In addition to the churches of the Morava School, the innovations in fresco painting of the Palaiological Renaissance are also characterized by more individuality, tending towards a stronger humanism and reinterpreting the often schematic specifications.

Portrait of the founder Stefan Lazarević, Manasija Monastery (Morava School, 1407-1418)

Iconostasis and wrought-iron choros in the Serbian Royal Monastery of Dečani (Raška School, 1328-1335)

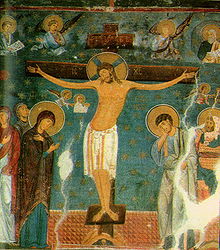

Crucifixion of Christ in the Serbian monastery of Studenica (ca. 1209)

Byzantine churches of the late phase are characterized by their polychromatic facades and ornamental design of friezes, window frames and rosettes. The biforium of the Kalenić monastery church is particularly richly decorated.

Kalenić Monastery, Serbia, Late Byzantine Trikonchos, after 1407.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is Byzantine art?

A: Byzantine art is a type of Christian Greek art that emerged in the Eastern Roman Empire around the 5th century and was prevalent until the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

Q: What other regions' art can fall under Byzantine art?

A: The term Byzantine art can also refer to the art of nations that shared their culture with the Eastern Roman Empire, which can include Bulgaria, Serbia, and Rus, as well as the Republic of Venice and Kingdom of Sicily even though they were part of western European culture.

Q: What is the term that describes the art produced by Balkan and Anatolian Christians who lived in the Ottoman Empire?

A: The art produced by Balkan and Anatolian Christians who lived in the Ottoman Empire is called "post-Byzantine."

Q: What are some traditions that began in the Byzantine Empire that are still present in some Eastern Orthodox countries?

A: Certain traditions that originated in the Byzantine Empire, particularly icon painting and church architecture, are still observed in Greece, Russia, and other Eastern Orthodox countries.

Q: What period is referred to as the Byzantine Empire?

A: The period in which Byzantine art emerged is known as the Byzantine Empire.

Q: When did Byzantine art become prevalent?

A: Byzantine art became prevalent around the 5th century in the Eastern Roman Empire.

Q: When did Byzantine art decline?

A: The decline of Byzantine art coincided with the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

Search within the encyclopedia