British Raj

![]()

This article needs a revision. More details should be given on the discussion page. Please help improve it, and then remove this tag.

British India (English British India or British Raj, from Hindi [राज] rāj [rɑːdʒ] ![]() ) narrowly refers to the British colonial empire in the Indian subcontinent between 1858 and 1947. British India was established after the suppression of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 by converting the previous possessions of the British East India Company into a crown colony. At the time of its greatest expansion, British India included not only the territory of what is now the Republic of India, but also the territories of the present-day states of Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, and parts of Kashmir under present-day control of the People's Republic of China. In 1876, Queen Victoria of Great Britain was proclaimed Empress of India, and the Empire of India (Indian Empire) was generally regarded as "the Jewel in the Crown of the British Empire". A distinctive feature of British India was that only about two-thirds of its population and half of its land area were under direct British rule. The rest was under the rule of native dynasties of princes who had a personal allegiance to the British Crown. There were more than 500 such princely states in all, varying greatly in size. Some maharajas ruled only a few villages, while some ruled vast lands with millions of subjects.

) narrowly refers to the British colonial empire in the Indian subcontinent between 1858 and 1947. British India was established after the suppression of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 by converting the previous possessions of the British East India Company into a crown colony. At the time of its greatest expansion, British India included not only the territory of what is now the Republic of India, but also the territories of the present-day states of Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, and parts of Kashmir under present-day control of the People's Republic of China. In 1876, Queen Victoria of Great Britain was proclaimed Empress of India, and the Empire of India (Indian Empire) was generally regarded as "the Jewel in the Crown of the British Empire". A distinctive feature of British India was that only about two-thirds of its population and half of its land area were under direct British rule. The rest was under the rule of native dynasties of princes who had a personal allegiance to the British Crown. There were more than 500 such princely states in all, varying greatly in size. Some maharajas ruled only a few villages, while some ruled vast lands with millions of subjects.

Under the name of India, this Union was a participant in both World Wars, a founding member of the League of Nations, the United Nations, and a participant in the Olympic Games of 1900, 1920, 1928, 1932, and 1936.

In 1947, British India gained its independence and the partition of India split it into two dominions, the Indian Union and Pakistan. The province of Burma (today's Myanmar) in the east of British India, on the other hand, had already been declared a separate colony in 1937 and finally gained independence in 1948.

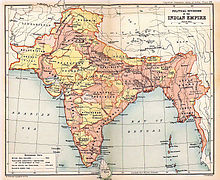

British India (purple) in the union of the British Empire 1920 after the First World War

Flag British India

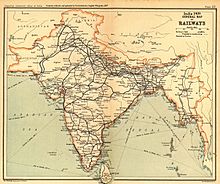

British India on a map of the Imperial Gazetteer 1909

History

Initial situation

After the disintegration of Mughal power with the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the Marath Empire (1674-1818, founded by Shivaji) rose in southwest India. The Maraths were the last major Indian power before British rule; besides them, the rulers of Hyderabad and Mysore still played a role in Indian politics, maintaining the fiction of a continuing Mughal empire until 1857 because it formed the legal framework of any rule.

The East India Company

→ Main article: British East India Company

In the 2nd half of the 18th century, the British or the British East India Company expanded their sphere of power in India after displacing the French (Carnatic Wars) and Portuguese (Goa). Initially, under Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive, they only secured their trading interests in Bengal. But a mere involvement in the Indian trade soon turned into tangible power interests. The company interfered in the disputes of the Indian princes (Battle of Plassey 1757) and took over the tax privilege in Bengal from the Mogul emperors. In 1758 Clive had still refused it, in 1765 he accepted it.

Soon the British proved to be ambitious and flexible rulers. Warren Hastings arrived in 1769, became governor of Bengal in 1771, and instructed his people to take over the administration: previously the company had always hidden behind the fictitiously maintained rule of the Nawab. He and his successors linked Indian soldiers with European warfare and British trade profits with Indian taxes, fought corruption (widespread among Indians and British alike), concluded treaties of protection, and took over swathe after swathe of land. Where they were not in power themselves, officials of the East India Company served as advisors.

In this, the British were able to organize a unified policy with the office of the governor-general and his advisory council (1773, then after 1784 a supervisory board in London). On the other side was an India torn apart by many conflicts, in which there was always a party willing to make a pact with the British. The technological advantage of the industrial revolution was added to this and from the beginning of the 19th century the East India Company was thus able to bring more and more parts of India under its control. In 1803 Delhi fell to the British, and the Mughal emperor (still the nominal ruler of India) came under their control.

As the conquests increased, however, the company itself became more and more disorganized. Its employees became millionaires via the bribes of the Indian princes and private trade, while the war costs had to be covered by the shareholders and the Company was saddled with a mountain of debt. Several acts therefore gradually transformed the East India Company from a trading company in 1773 (Regulating Act), 1784 (India Act), 1793, 1813 (far-reaching abolition of the trading monopoly), 1833/4 (administrative corporation without trading accounts) into an autonomous administrative organization under the control of the British government. The commercial employees were replaced by civil servants and India was opened to British trade, i.e. the Company's monopoly was broken.

Adjustment attempts

The success of the British was painstakingly bought, above all they could not at first combine the divergent cultural ideas of administration. Warren Hastings, for example, left the Islamic criminal law in place because it was easy to administer. Then, from 1774, there was a Supreme Court under English law, but, according to a 1781 determination, it applied only to Europeans. The cruelest punishments of Islamic law (impalement, mutilation) were abolished, but until 1861 there was no binding penal code; the British relied instead on native legal experts. English did not become the language of administration until the 1830s; before that it was Persian. All in all, the British were unable to order and unify administration until well into the 19th century: there were superfluous offices, contradictory treaties, misinterpretations of earlier legal practice, etc. - in short, chaos in all matters of property, taxation, officialdom and sovereignty.

Efforts were also made in the last decades of the 18th century to adapt India's time-honoured agricultural system to the European system of land ownership. Thus, land indebtedness through speculation was initiated (land could be sold under the British in case of insolvency; 1793 "perpetual lease" creates new landowners).

Lord Dalhousie and the Road to the Great Rebellion 1857

→ Main article: Indian Insurrection of 1857

In the course of the 19th century, civil servants (e.g. Lord Macaulay, Minister of Justice), who made it their programme to transform India in the English sense and to impart progressive, Christian values, took the place of the businessmen who had once striven for intensive knowledge of the language and the country. For example, in 1834, marriages and social relations with Indians, which had been common until then, were banned and a separation between the two groups was introduced.

Lord Dalhousie held the office of Governor-General from 1848-1856. He created with great energy a tight fabric of a tightly organized administration. The old freedoms of the kind "Create order in the country, make the people happy, and see that there is no spectacle" now no longer existed for the civil servants (many of whom were also officers working in the civil sector). The practice of adoption of heirs to the throne, which was in force in India, was subjected to the right of objection of the Governor-General, and Lord Dalhousie thus annexed a handful of these dependent princely states (so-called Doctrine of Lapse). Besides, there was a repeatedly denounced mismanagement in Avadh (capital: Lucknow, today part of Uttar Pradesh), which served him as a pretext to annex it as well in 1856 (albeit this time on the instructions of his directors in London).

The landowning class was also affected by the Lord's reforms. In the Deccan, some 20,000 plots of land were expropriated, sometimes under dubious claims, without respect for time-honoured values and customs and without compensation for injustice. (The Jats around Delhi, for example, had their grazing land assessed as farmland for tax purposes - they suffered from the tax). In prisons, caste segregation was abolished by letting everyone eat together. The Brahmins were deprived of their authority by modern Western education.

The consequences of this vigorous policy were felt in the Sepoy Rebellion. This uprising is variously seen as the first independence movement against the British, as it was based on resistance to curtailment of ancestral rights and traditions. There was not only a discontent that cut across all castes, but also ancestral leadership for an uprising: for example, Nana Sahib, responsible for the massacre of English women and children in Kanpur, was the adopted son of the last Peshwas Baji Rao II and was deprived of his pension by Dalhousie's policies. He had an able general named Tantia Topi. The Rani of Jhansi Lakshmibai, a legendary rebel leader, had been deprived of the succession of her adopted son. The ex-king of Avadh also had his agitators in the sepoy regiments and many sepoys were from there.

The Indian soldiers (sepoy), trained on the European model, were commanded by British and numbered 187,000 men in 1830 as against 16,000 British. Indians could only rise to the rank of company commander. The balance of forces on the eve of the revolt was as follows: 277,746 sepoys against 45,522 British soldiers. Nevertheless, the British were victorious and, in retrospect, Dalhousie's policies established not only the period of imperialist British India but also the modern Indian unitary state.

After the Sepoy Uprising

After the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857/58, the rule of the East India Company ended and its last powers or special rights were transferred to the Crown.

This was done with the Government of India Act 1858, passed by the British Parliament on August 2, 1858, at the request of Prime Minister Palmerston. The key points of the Act were:

- the takeover of all territories in India from the East India Company, which at the same time lost the powers and control hitherto vested in it.

- the government of the possessions in the name of Queen Victoria as a crown colony. A Secretary of State for India was placed at the head of the India Office, which supervised the official administration from London.

- the assumption of all the assets of the Company and the entry of the Crown into all contracts and agreements previously entered into.

At the same time, the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah II was deposed. From now on, the Council of the Governor General ruled, which was subordinate to the India Office in London. The Indians were promised the same rights as the British and also access to all government posts. In fact, however, sharp conditions of admission made it almost impossible for Indians, as a rule, to attain higher positions in the administration. The princely states could again be passed on by adoption.

Empire

In 1876, Queen Victoria of Great Britain assumed the title "Empress of India/Kaisar-i Hind", thus documenting that India had become the mainstay of the British Empire. The title of Emperor was created not least to provide a kind of legal basis for British rule: after all, the East India Company had ruled in the name of the Mughal Emperor until the end. The "Empire of India" was divided into the territories under direct control (just under 2/3 of the country) and the territories under native princes, the so-called Princely States or Native States. Therefore, the additional title of Viceroy was introduced for the Governor General in 1858.

Burma was occupied by Great Britain in several wars (1852, 1866 and 1886) and also annexed to the Empire of India (until 1937). There were also repeated protracted battles on the north-western border with Afghanistan, where the feared Russian advance was also to be countered. However, direct control over Afghanistan proved impracticable. In 1893, the Durand Line was drawn, which still forms the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Management structure

At the head of the provincial administrations, depending on their size, a governor or (chief) commissioner:

- Ajmer-Merwara: separated from the North West Provinces in 1871.

- Baluchistan: The parts of Baluchistan under direct rule were organized as a province in 1887, the first commissioner being Robert Groves Sandeman.

- Bengal (Bengal): 1765 Presidency of the British East India Company. Expanded after the wars against the Maraths. Province in 1858, included what is now Bihar. Partitioned in 1874, 1905-1912, Bihar and Orissa separated on reunion of heartlands.

- Berar: Territory of the Nizam of Hyderabad, under British administration from 1853, united with the Central Provinces in 1903.

- Bombay: 1668 Presidency of the British East India Company. Enlarged in the wars against the Maraths. 1858 Province.

- Delhi, was carved out of Punjab as its own province (Delhi Imperial Enclave) after the Calcutta government moved there on Sept. 30, 1912, and the area was expanded in 1915.

- Madras (officially Presidency of Fort St. George): founded in 1640, Presidency of the British East India Company in 1652, greatly expanded in late 18th century. 1858 Province.

- Mysore & Coorg: 1869-1881, thereafter separate princely states again.

- Nagpur: created in 1853 from an annexed princely state, annexed to the Central Provinces in 1861.

- North-Western Provinces (capital Agra): separated from the Presidency of Bengal in 1835; joint administration with Oudh in 1877; formal unification of the two provinces in 1902 and renaming as United Provinces of Agra & Oudh.

- Oudh: princely state annexed in 1857, administered by the Northwest Provinces since 1877.

- Punjab: Formed in 1849 from territories acquired in the Sikh wars. Reduced in size in 1901 when the North-West Frontier Province was formed.

- Central Provinces: Formed in 1861 from the union of Nagpur with Saugor and Nerbudda Territories. Renamed Central Provinces and Berar after the annexation of Berar in 1903.

Fringe

- Aden and Persian Gulf Residency: separated from Bombay Presidency in 1932; the former became an independent Crown Colony in 1937.

- Assam: separated from Bengal in 1874, enlarged in 1905 and renamed Eastern Bengal & Assam.

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands: organized as a separate province in 1872.

- Burma: Lower Burma (Lower Burma) 1862 formed from Arakan, Pegu and Tenasserim, 1886 extended by Upper Burma (Upper Burma), 1937 separated from the empire India and raised to the independent crown colony.

Administration after 1919

Under the provisions of the Government of India Act of 1919 (in force from 1 April 1921), eleven provinces existed under one Governor (Governor's Provinces). He was responsible to the London Parliament and appointed for five years. Attached to him was a Council of two to four appointed members. In so far as Indians were allowed to decide certain questions, they provided two to three specialist ministers. Each province had a Legislative Council elected on a three-year rotation. In 1935, the provinces of Sindh (capital Karachi) and Orissa were newly created. The North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) was carved out of Punjab on 9 November 1901 and administered from Peshawar.

The provinces were further divided into Divisions under Commissioners, in Madras they were called Collectorates. These were in turn divided into Districts (1935: 273), the entire administration of which was headed by a District Officer or Deputy Commissioner. Sindh was separated from Bombay in 1936. Panth-Piploda was ceded from the princely state of Jaora in 1942.

Representations of the people

| Provinces (before 1935) | Capital (S: in summer) | Members of the Council of State | Members of the Legislative Council | Members of the Provincial ParliamentTotal | Number of Princely States |

| Madras | Madras, S: Ootacamund | 2 / 5 | 4 / 16 | 132* (34 / 098) | - — |

| Bombay | Bombay, Poona; S: Mahabaleshwar | 2 / 6 | 6 / 16 | 114* (28 / 086) | 152 |

| Bengali | Calcutta, S: Darjeeling | 2/ 6 | 5 / 17 | 140 (26 / 114) | - — |

| United Provinces of Agra and Oudh | Allahabad, S: Nainital | 2 / 5 | 3 / 11 | 123* (23 / 100) | - — |

| Punjab | Lahore, S: Shimla | 3 / 3 | 2 / 12 | 094* (23 / 071) | 021 |

| Bihar & Orissa | Patna, Ranchi | 1 / 4 | 2 / 12 | 103 (27 / 076) | 026 |

| Central Provinces (with Berar) | Nagpur, S: Pachmarhi | - / 2 | 3 / 06 | 073* (18 / 055) | 015 |

| Assam | Shillong | - / 1 | 3 / 06 | 053 (14 / 039) | 016 |

In Myanmar, women were granted the right to vote in 1923. However, this was, just as for men, a census suffrage, which depended on the tax revenue. Since a poll tax was imposed only on men, and therefore many more men than women paid tax, it is not possible to speak here of comparable criteria for the sexes. Women's suffrage with high income qualification also existed at the all-India level and at the legislatures marked with *.

In addition, there were five provinces, which were headed by a Chief Commissioner appointed for three years; without popular representation, they were directly subordinate to the central government:

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands with the capital Port Blair, whose notorious Circular Jail was used for the exile of political prisoners. In addition to the 28,000 inhabitants (1937) there were 6,158 convicts; in 1921 there had been 11,500.

- Ajmer-Merwana with the summer capital Mount Abu

- Baluchistan, capital Quetta; the tahsil Quetta was part of the state of Kalat until 1879. Bori was added in 1886, Khétran in 1887, Zhob and Kakar Khurasan in 1889, Chagai and West Sinjrani in 1896, Nuski Niabat in 1899, and Nasirabad in 1903.

- Delhi's status remained unchanged; it had a legislature of 41 appointed and 104 elected representatives

- Coorg was under the Resident of Mysore since 1881. The consultative assembly had 20 members, five of whom were from the civil service.

Princely States

→ Main article: List of Indian princely states

Among the princely states grouped as protectorates under various agencies (1941: 560, 119 of which had salute rights).

Time of the independence movement

In 1885, the Indian National Congress (INC) was founded, which in the beginning only had the function of approaching the colonial government with requests and petitions. It was initially a rather elitist association, "educated in the West and influenced by European thinking, eager to assume governmental responsibility" (Gita Dharampal-Frick; Manju Ludwig and lima raja: Colonization and Independence, 153). As history progressed, it was then this same INC that had a decisive impact on India's independence. Due to the growing influence of Hindus in the INC, the rival Muslim League was formed in 1906. The INC and the Muslim League jointly drafted a declaration in 1916 with demands for Indian independence (Lucknow Pact). This was answered by the British government in August 1917 with a political declaration of intent to allow India a gradual transition to self-government.

After the First World War, in which 1.3 million men of the Indian Army fought on the British side, India, which remained under British rule, was one of the founding members of the League of Nations. With Mahatma Gandhi the INC got its most famous and charismatic leader. He knew how to move a large crowd and take the process of India's independence to the next level. Thus, the inter-war period saw non-violent resistance against the British rule. In this Gandhi strove for the political unity of Hindus and Muslims, he dreamed of a unified, undivided India. In his efforts for independence, religious and political motivations were intertwined in a peculiar way. For example, his political measures were always "accompanied by religious rituals (prayers, fasts, processions)" (Michael Bergunder: Pluralism and Identity, 162). In 1919, the Amritsar Massacre took place, in which at least 379 demonstrators were shot dead by British soldiers. Between 1920 and 1922, the so-called Campaign of Non-Cooperation, initiated by Gandhi, took place. In 1930, the famous Salt March took place. But despite the great national as well as international response, no far-reaching changes could be achieved in terms of co-government or even independence. In 1935, the Government of India Act of 1935 initiated elections to provincial assemblies, which the INC won in seven out of eleven provinces in 1937. In the same year Burma was elevated to the status of an independent crown colony.

Although the Indian public was not at all sympathetic to the Nazis and welcomed Britain's attitude towards Germany, India's leading political forces (such as Subhash Bose) declared that they would enter the war only if, in return, India was given its independence. The British Governor General Lord Linlithgow declared a state of war of the Indian Empire with Germany at the outbreak of the Second World War, but without consulting the Indian politicians. This move made it clear how little the co-government won so far actually meant in terms of self-determination, so demands were made for independence at the end of the war by the INC. However, these demands were rejected and the ensuing uprisings and riots were put down violently. At the beginning of the war, India had an army of about 200,000 men; by its end, 2.5 million men had enlisted, the largest volunteer army in World War II. In this war, according to official figures, India lost 24,338 soldiers, 64,354 were wounded and 11,754 remained missing. Due to the lack of food caused by the war, an estimated two million people starved to death (see also Famine in Bengal 1943).

After the Second World War, contrary to the announcements, there were negotiations about a possible independence of India. Besides Mahatma Gandhi, his successor Jawaharlal Nehru as representative of the INC and also Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the leader of the Muslim League, who pursued the foundation of Pakistan as a goal, were involved. Due to the difference in interests and ideas, there was a quarrel and a sudden end to the negotiations. The result was unrest between Muslims and Hindus, and since Great Britain did not feel able to control the situation, the prospect of independence for both states was held out. This was not supposed to happen until June 1948, but the British spontaneously decided to accelerate the transfer of power already in June 1947. According to the two-nation theory (see also Mountbatten Plan), the country was divided into a Hindu part (today's India) and a Muslim part (today's Pakistan). The then Pakistan also included the now independent Bangladesh. The hasty transfer of power and ill-considered border demarcations led to serious conflicts between the two states.

The fact that a two-nation solution came about at all is connected, among other things, with Gandhi's religious-national interests. For him, India "presented itself first and foremost as a religious idea" (Michael Bergunder: Pluralismus und Identität, 162). Gandhi understood Hinduism as an inclusive religion. It was clear to him that other religions also represented a path to God, but at the same time, at least implicitly, the primacy of Hinduism was valid for Gandhi. An example of this is his commitment to the sanctity of the cow. He wanted to assert this against Indian-Islamic groups and thus disputed their religious convictions. Jinnah's demand in the negotiations from 1945 for a Muslim Pakistan is to be understood as a demarcation from Gandhi's united India, which the latter thought in terms of an encompassing Hinduism. Jawaharlal Nehru, on the other hand, who played a major role in the later negotiations, advocated a strict separation of religion and politics. For him, therefore, India's politics had to be under the sign of secularism and not of a Hindu-national consciousness.

Quit India Movement 1942

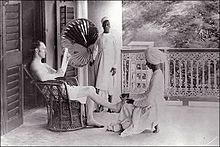

A Briton in India

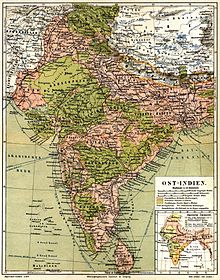

Map of the Empire of India

Silver rupee from the "Madras Presidency", minted before the standardization of coins in 1835; until then the British followed the native design

Arthur Wellesley leads his troops into the Battle of Assaye, 1803.

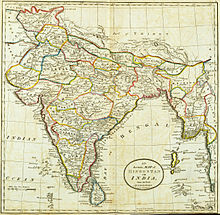

Map of the Indian subcontinent ("Hindostan") from the year 1814

Relief from Lucknow, 1857

"British Raj", the administrative division

Economy and social affairs

Under the rule of the East India Company, India had increasingly degenerated into an economic object of exploitation. Indian weaving as an industry, for example, was ruined by the advent of machine production in Europe: The European market was closed, and at the same time Britain introduced ready-made garments into India; India became an outlet, while textile exports declined rapidly.

The economic monopoly of the East India Company had already been abolished in 1813, but it still held the administration and had some privileges. Alongside it now rose so-called agency houses, which financed their own ventures but did not yet have sufficient capital cover. Investments were kept within narrow limits, because the European and American markets were safer and had better logistical conditions to offer. A series of Agency House bankruptcies and the cessation of all Company trading in 1833/4 therefore allowed an Indian to enter: Dwarkanath Tagore (1794-1846). Thereafter, the influence of British capital increased again, for example in connection with railway construction. As a countermeasure to the poor infrastructure, the expansion of the Grand Trunk Road began in 1839, a road that had already existed since Mughal times, starting in Delhi and extending to Calcutta. Banks were established, steamers were used on the rivers, and from 1853 the construction of the first railway line (already projected in the 1840s) began.

Other changes occurred in the social sphere. Slavery was abolished and widow burning was banned in 1829, at least in the area under direct British administration. In 1829 the government also cracked down on the Thugs, a murderous sect of the goddess Kali. One of the pioneers of a kind of spiritual renewal of India was the Brahmin son Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833), who opposed the caste system, widow burning, and oppression of women. His aim was to reconcile Hinduism and Christianity, because he assumed that both faiths were moral and rational at their core.

After the Sepoy Uprising, Indians were promised the same rights as British, and also (if qualified) access to all government posts. This resulted in the rise of many modern educated Indians in the administration, including higher posts in the army. Even under direct British rule, controlled development of the colony took place, following the principle of extracting raw materials in the colony, processing them in the homeland, and at the same time using the colony as an outlet for finished products. Therefore, India was hardly industrialized, only infrastructure development - especially railways - took place. The colony's main products were cotton and tea as well as jute; large quantities of grain (wheat) were also exported to Great Britain.

The beneficiaries of India's modernization (roads, canals, railways, factories, colleges and universities, newspapers, etc.) were, despite everything, primarily the British. For ultimately the Indian administration was under the control of the India Office in London and therefore the British Parliament, not the Indians. The language of the upper classes was English. The laws applied to all, but were made by the British, and the economic winners were first them, then the emerging Indian middle class.

Technical achievements such as printing were taken up by the Indians themselves, and a vibrant Indian press emerged.

Modernization bypassed the mass of peasants (often uneducated and indebted) and artisans; for them it was an alien commodity with no relation to their own tradition. On the other hand, the switch to the cultivation of export products such as cotton instead of basic foodstuffs and the high tax burden exacerbated poverty in the countryside. Drought and floods caused repeated famines with millions of victims. In line with their laissez-faire economic policy, the British did little to help the starving.

Public finances

Especially the numerous colonial wars and the maintenance of the army caused massive expenses. When the Crown assumed direct rule in 1858, it not only took over the debts of the East India Company, but also generously compensated its shareholders, which led to a comparatively high national debt (India Debt). The state finances were mostly in deficit, which had to be compensated by an export surplus and thus led to the permanent impoverishment of the country through a permanent outflow of money (drain). Inflation must be taken into account in the figures given below: Price Index 1873 = 100, 1913 = 143, 1920 = 281, based on all India, which received a further boost during the Second World War.

Revenue side

The most important source of revenue was and remained the land tax (land revenue), although its overall share declined over time. The Permanent Settlement (1793) created a structure modelled on the British system. Large landowners (zamindar) were indirectly responsible for collecting the tax. Middleman income from land rent increased sevenfold between 1793 and 1872, but only slightly more than twice the tax was delivered. In the South, a more direct form of tax payment, the Ryotwari system, was common. Between 1881 and 1901, revenue increased by a further 22% At the local level, a tax was still levied on villages to pay village headmen (chaukidar). Quite a few zamindars invented their own levies, such as for the upkeep of their elephants. Tax collection was often carried out by extortion, execution, but also frequently by force.

The introduction of forest revenue by the British particularly affected the tribals, who had traditionally used forests as common land, and led to numerous uprisings in the 19th century, all of which were bloodily suppressed.

Plans to introduce an income tax had been drafted since 1860, but it was not until 1886 that it was introduced to cover the high war costs of previous years. The tax base was greatly expanded in 1917.

The sales tax was regressive and was increased sharply in 1888. Excise duties, e.g. on alcohol, gained in importance (1882: Rs. 6 million, 1920: 54 million). The salt tax, which particularly affected the common people, was never significant in terms of the total amount. A license fee was due for the permission to operate a business.

Customs duties were kept low for political reasons so as not to interfere with the import of manufactured goods from the mother country, especially fabrics. Stamp duty was charged for the activities of authorities and courts.

Expenditure side

The largest item in the Indian national budget was always the cost of the army. This included not only expenses in India, but also a large part of the British war costs in 1885-86 against the Mahdi and in the Boxer Rebellion (1900/01) were borne by India, furthermore the costs of all overseas stationed Indian units. The share of the in the budget rose from 41.9% in 1881 to 45.4% in 1891 and then to 51.9% by 1904. One third of the army had to be made up of European soldiers after the Sepoy uprising, who received about three times the pay of an Indian.

After 1873, there was a gradual devaluation of the rupee, which was based on the silver standard, against the gold-backed pound. This was particularly significant for the payment of Home Charges. These were expenses settled in pounds and paid to the mother country. They amounted to £17.3 million in 1901, of which 6.4 million was interest on guaranteed bonds arising from railway construction, a further three million was used to service the general national debt, £4.3 million was for the maintenance of British troops only £1.9 million was for the purchase of supplies. This also included pensions for former members of the Indian Civil Service (ICS) and British officers, together £1.3m. The costs of the India Office in London were also paid from this.

The railway network of British India in 1909 was about 45,000 to 50,000 km.

Questions and Answers

Q: What does the term "British Raj" mean?

A: British Raj is a term used to refer to the direct rule of the British Empire over areas that had been conquered by them, known as British India. It includes the influence of many independent princely states under the overall authority of the British crown.

Q: When did British rule end in India?

A: British rule ended on 15 August 1947.

Q: How many people were part of the 1861 census in India?

A: The 1861 census showed that there were 125,945 people in India, with 41,862 civilians and 84,083 European officers and men of the Army.

Q: What countries are included in what was formerly known as British Raj?

A: The area now known as British Raj is located within India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Myanmar.

Q: Was Burma part of Undivided India?

A: No, Burma became its own separate colony from 1937 onwards and was not considered part of Undivided India.

Q: How many soldiers were there in 1880 for both native and princely armies combined?

A: In 1880 there were a total of 350,000 soldiers between both native and princely armies combined.

Q: What happened during partitioning between India and Pakistan after Britain left?

A: During partitioning between India and Pakistan after Britain left many people died due to conflict over Jammu & Kashmir which was an independent princely state at that time but is now divided between them both.

Search within the encyclopedia