Breton language

![]()

This article or section is still missing the following important information:

Systematic presentation of the grammar (also word formation and morphology), the sound system (phonetics and phonology) in IPA (not on the basis of spelling!), a language example (short, coherent text), specialist literature (cf. format template language) and individual references.

Help Wikipedia by researching and adding them.

Breton (Breton Brezhoneg) is a Celtic language. Like Welsh, Cornish and the extinct Cumbrian, it belongs to the subgroup of Britannic languages. Breton is spoken in Brittany by the Britophone Bretons, making it the only modern Celtic language native to mainland Europe. It does not trace its origins to the ancient Celtic language of Gaul. Its area of distribution is Bretagne bretonnante, which today still consists of the western areas of Brittany, i.e. the department of Finistère (Penn ar Bed) and the western part of the departments of Côtes-d'Armor (Aodoù-an-Arvor) and Morbihan (Mor-bihan). The eastern part of Brittany is the Pays gallo, in the western parts of which Breton was also spoken in the past, while Breton has never been able to penetrate to the east of Brittany (around Nantes, for example, one of Brittany's historic capitals).

Language policy and present situation of Breton

The number of speakers of Breton has decreased dramatically since the 1950s. As the French Republic does not collect figures on the number of speakers of the languages spoken on its territory, all figures are based on estimates. It is generally assumed that in 1950, about 1,200,000 people spoke Breton, of whom some tens of thousands were unable to communicate at all or fluently in French. With the extinction of the monolingual population, a rapid transition to French began, as most Breton-speaking families now began to raise their children monolingually in French to avoid discrimination at school and at work.

According to a study by Fañch Broudig (Qui parle breton aujourd'hui? , 1999), there were still 240,000 Breton speakers at the turn of the millennium, but a large proportion of them no longer used Breton in their daily lives. According to this, about two thirds of the speakers are said to be over 60 years old and only half as many people actually still use the language in everyday life. The Association of Divan Schools estimates the number of people who understand Breton at up to 400,000.

For a long time, Breton enjoyed no or only partial official recognition by the French state and was systematically suppressed in the 19th and 20th centuries (discrimination at school, negation in official correspondence). The administrative and school language of the French Republic is French, and this principle was enforced in order to spread the national language throughout the country. The period of active suppression by public authorities lasted until the 1960s. However, although bilingual place-name signs have been put up for some years on the initiative of numerous municipalities (particularly in the area to the west of Guingamp), place names are still officially recognised only in French spelling. For example, it is still possible today that letters addressed with Breton place names cannot be sent.

The Breton language is promoted by a strong Breton regional movement made up of numerous local and regionally organised initiatives and associations, so that today (as of 2020), for example, there are 55 Breton-language Diwan schools. Classes with some teaching in Breton have also been set up in private Catholic schools (Dihun association) and in some state schools (Div Yezh association). However, according to 2005 statistics, there were 2896 pupils in Diwan, 3659 pupils in private Catholic schools with Breton classes and 3851 pupils in bilingual classes in public schools, compared with 360,000 pupils in purely French-language classes.

Since 1999, the Ofis publik ar Brezhoneg has been working to preserve the Breton language and culture.

In December 2004, the Breton regional government announced its intention to promote the continued existence of Breton, which was a sensation in post-revolutionary France. In particular, the number of places in Breton immersion classes (modelled on Diwan) was to be increased to 20,000.

Few families currently have children growing up with Breton as their mother tongue. Although there are several tens of thousands of speakers who have learned Breton in order to preserve it, hardly any of them have a knowledge equivalent to that of a native speaker. The Breton media (television broadcasts on FR3 Ouest and TV Breizh, radio broadcasts, magazines) are for the most part managed and presented by non-native speakers with quite varied linguistic skills.

UNESCO classifies Breton as a "seriously endangered language".

The problem of surveys on language use

The problem with surveys asking questions such as "Do you speak Breton?" is that they do not always take into account the actual linguistic competence of the respondent. Thus, language enthusiasts who have little or no knowledge of Breton, but who want to support it out of conviction, answer "yes", not least to increase the percentage of Breton speakers. In contrast, many of the older native speakers of Breton are ashamed because of the low prestige of the language in their youth, so that honest answers cannot always be expected from this population group either, and they often deny their knowledge of Breton altogether.

Bilingual street signs in Quimper

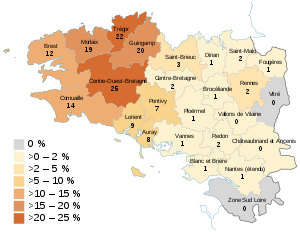

Percentage of speakers of Breton in Brittany in 2018 (result of a telephone survey with 8162 participants).

Play media file Breton as a spoken language (Wikitongues project)

Dialects

The Breton language is divided into four dialects: Leoneg, Tregerieg, Gwenedeg and Kerneveg.

- Gwenedeg (French vannetais) is spoken around the town of Vannes (Breton Gwened) and is the least common Breton dialect, spoken by only 16% of all Bretons.

- Kerneveg (French cornouaillais) is spoken around the city of Quimper (Breton Kemper) and is the largest Breton dialect, accounting for 41% of the total number of speakers. Kerneveg is most closely related to Cornish, the language of Cornwall which died out on the opposite shore of the English Channel.

- Leoneg (French léonard) is spoken in Léon (Breton Bro Leon), which covers the northern part of the department of Finistère (Breton Penn ar Bed), and is the second most widely spoken Breton dialect with 24.5%.

- Tregerieg (French trégor(r)ois) is used around the town of Tréguier (Breton Landreger) by 18% of Breton speakers.

Kerneveg, Leoneg and Tregerieg (the so-called KLT dialects) are comparatively close to each other. Gwenedeg differs considerably from these. This dialectal difference in particular has made the development (and acceptance) of a unified written language very difficult. Several spelling systems coexist; the most widely used is Peurunvan (French orthographe unifiée), also called Zedacheg because of the typical use of the digraph zh (French zed ache), which is pronounced as [z] in KLT dialects but as [h] in Gwenedeg. Another significant difference is the word stress, which is on the penultimate syllable in the KLT dialects but on the last syllable in Gwenedeg (e.g. brezhoneg: KLT [breˈzonek], Gwenedeg [brehoˈnek]).

The traditional dialects are rapidly losing importance due to the decline in their number of speakers, while a new standard is emerging in radio and television. Used mainly by non-native speakers, it is phonologically strongly influenced by French, but uses less vocabulary of French origin than the dialects. Traditional speakers would, for example, use the (originally French) avion for 'plane' - stressed on the penultimate syllable, mind you - whereas the neologism nijerez (literally 'aviatrix') is preferred in the standard. Since a large proportion of the speakers of this learned, non-native standard come from around the University of Roazhon (Rennes), this variant of Breton is also known as Roazhoneg. This is quite pejorative: since traditionally Breton was never spoken in Roazhon, dialect speakers thus emphasize the "artificiality" of the standard. The French influence on phonology is most noticeable in prosody: native French speakers often replace the Breton word accent (on the penultimate syllable of each word) with the French phrase accent (on the last syllable of each sentence).

Search within the encyclopedia