Ageing

![]()

This article deals primarily with biological-medical aspects; for aging in the sociological-social sense, see Age; for other meanings, see Aging (disambiguation).

Aging is a progressive, irreversible biological process of most multicellular organisms that gradually leads to the loss of healthy body and organ functions and eventually to biological death. Aging is by far the most important risk factor for various diseases such as cancer, coronary heart disease, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and chronic kidney failure. The maximum lifespan that an individual can achieve is significantly limited by aging.

Aging, as a physiological process, is a fundamental part of the life of all higher organisms and one of the least understood phenomena in biology. It is generally accepted that a number of different highly complex mechanisms, many of which are still unexplained, are responsible for ageing. They influence and limit the lifespan of biological systems such as cells, the organs, tissues and organisms built from them. There are many different answers to the question of why organisms age (theories of ageing), but to date there is no scientifically accepted comprehensive answer.

Gerontology, also called the science of old age and ageing, is the science of human life in old age and of the ageing of people. The basic biological discipline - without focusing on the human species - is biogerontology.

Time commands age to destroy beauty , oil painting by Pompeo Batoni from 1746

The gradual age of man. Such representations, also called staircases of life, were very popular from the 17th century onwards. The human life course was usually represented in ten stages of ten years each. The climax of life was placed in the fifth decade, since it was assumed that at this age man would come closest to perfection.

Definition and delimitations

There is no generally accepted scientific definition of ageing itself. A broader, more recent definition regards every time-related change that takes place in the course of an organism's life as ageing. This includes both the maturation processes in childhood, which are seen as "positive", and the degenerative phenomena in old adults, which are seen as negative. Derived from this definition, aging of higher organisms begins immediately after the union of sperm and egg and leads to its death. Other gerontologists define aging only in terms of the negative temporal changes of an organism, for example the loss of function of organs or senescence after adolescence. In 1960, the German physician and founder of gerontology, Max Bürger, defined ageing as an irreversible time-dependent change in the structures and functions of living systems. According to Bürger, the totality of physical and mental changes from germ cell to death is called biomorphosis. Which changes are assigned to ageing, however, leaves much room for interpretation. The US gerontologist Leonard Hayflick defines ageing as the sum of all changes that occur in an organism during its lifetime and lead to a loss of function of cells, tissues, organs and finally to death. For Bernard L. Strehler, aging of a multicellular organism is defined by three conditions:

- Universality: The processes of aging are present in all individuals of a species with the same regularity.

- System immanence: Aging is a manifestation of life. The processes of ageing also take place without exogenous factors.

- Irreversibility: Aging always runs in one direction only. The changes that take place are irreversible.

Beyond these scientific definitions, aging in humans is a socially complex multi-dimensional traversal of the lifespan from birth to death. Genetic disposition and biological changes are the central element of the complex interaction between humans and their environment. The processes of aging are subject to subjective, biological, biographical, social, and cultural evaluations. Ageing itself is a phenomenon with biological as well as psychological and social aspects.

In common parlance, aging is largely associated with negative changes, with decay, deterioration and degeneration of sensory and physical abilities. These changes are better reflected by the term senescence. The term aging should be used only for inanimate matter.

The term old age usually refers to the period of life of older people, the "old people", and the result of growing old. In contrast, ageing is primarily concerned with the processes and mechanisms that lead to old age and that underlie growing old and being old.

- See also: Old age as a stage of a person's life at the end of life, in particular also the image of old age.

Primary and secondary ageing

Aging is divided into two forms, primary and secondary aging.

- Primary ageing, also called physiological ageing, is caused by cellular ageing processes that take place in the absence of disease. This form of ageing defines the maximum attainable age for an organism. In humans, this value is about 120 years (see also: Oldest human) and is given the Greek letter ω (omega, symbol for the end). Other authors set ω to the value 122.45 years. This is the age Jeanne Calment reached at the time of her death, and the highest verified age of a human being to date. To date, there are no known evidence-based agents (for example, drugs) or other treatments that can delay or even prevent primary aging in humans. In various animal models, primary aging could be delayed by certain measures, such as caloric restriction or the administration of rapamycin.

- Secondary ageing, on the other hand, refers to the consequences of external influences that shorten the maximum achievable lifespan. These can be, for example, diseases, lack of exercise, malnutrition or the consumption of addictive substances. Secondary ageing can therefore be influenced by lifestyle.

The subject of this article is essentially primary aging. The two forms of ageing cannot always be clearly distinguished in practice. Gerontology is the science of ageing and ageing and accordingly deals with all aspects of ageing. Biogerontology deals with the biological causes of ageing. Geriatrics, on the other hand, is the study of the diseases of old people.

Senescence

Senescence (Latin senescere 'to grow old', 'to age') is not a synonym for aging. Senescence can be defined as an age-related increase in mortality (death rate) and/or decrease in fertility (fertility). Aging can lead to senescence: Senescence is the degenerative stage of aging. Only when the deleterious effects accumulate gradually and slowly should one speak of senescence. Often, however, it is not possible to distinguish neatly between aging and senescence. The beginning of senescence is usually placed at a time after the end of the reproductive phase. This is an arbitrary determination that does not do justice to the processes in different species. For example, vertebrates show phenomena of senescence such as the accumulation of the age pigment lipofuscin even during their fertile phase, and water fleas lay fertile eggs until their death despite senescence. A typical characteristic of senescence is the increase in mortality rate over time.

Many age-related changes in adult organisms have little or no effect on vitality or lifespan. These include, for example, the greying of hair due to reduced expression of the catalase CAT and the two methionine sulphoxide reductases MSRA and MSRB.

The aging of the cells (cell aging) is called cell senescence.

See also: Senescence in plants

Life expectancy and life potential

→ Main article: Life expectancy

Both the average life expectancy and the maximum achievable life span ω vary greatly from organism to organism. Mayflies and Galápagos giant tortoises are extreme examples. The statistically determined life expectancy of an individual is considerably less than the maximum lifespan for each organism. Catastrophic death from disease, accidents or predators (predators) means that most organisms in the wild do not come within ω of their value. Only a small fraction of deaths are age-related. In humans, over their evolutionary history, especially the last 100 years, an increasing convergence of the mean life expectancy of the population to the maximum life span can be observed.

Non-biological forms of ageing

In addition to biological aging, there are other forms of aging in humans. These include psychological ageing. This refers to changes in cognitive functions, experiences of knowledge and the subjectively experienced demands, tasks and opportunities of life. Ageing can also lead to the development of strengths, such as area-specific experiences, action strategies and knowledge systems.

Social ageing is defined as the changes in social position that occur when a person reaches a certain age or status passage. In industrial society, retirement and entry into retirement age is the status passage at which social ageing begins. Aspects of social aging are addressed by disengagement theory (the self-determined withdrawal from social contact), activity theory, and the continuity theory of aging, among others. Since the 1990s, the World Health Organization (WHO) has been promoting the concept of active ageing in an attempt to preserve competences in ageing and old people and to make them effective in the form of participation.

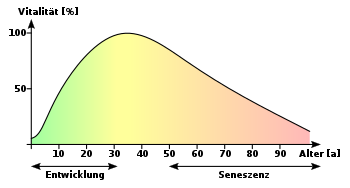

The biological age of an organism (here in humans) is characterized by its vitality. After birth, this value rises to a maximum during the developmental phase. In senescence, it falls continuously and reaches zero at death. With a normalized time axis, similar curves result for all mammals and vertebrates.

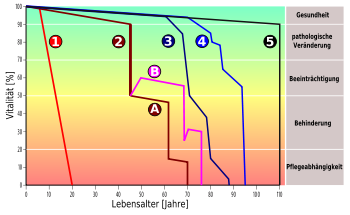

Examples of different aging processes: (1) Aging with progeria (premature senescence) (2) Accelerated aging due to risk factors such as high blood pressure, tobacco smoking, etc. (2A) After an acute event, for example a stroke, without therapeutic measures. (2B) In the case of therapeutic measures after an acute event, an improvement in vitality and life expectancy can be achieved. (3) A rapid functional impairment with a long phase of disability and dependence on care, as is typical in the case of dementia. (4) An example of "normal" ageing with only minor impairments even in old age. (5) An ideal-typical course of ageing.

Ann Pouder (1807-1917) on her 110th birthday. She is one of the few people who have reached the maximum attainable age.

The Ages of Life and Death. Painting by Hans Baldung around 1540

Organisms not affected by aging

Aging is a process that accompanies many higher organisms throughout their lives and can ultimately lead to their death. Many organisms with differentiated somatic cells ("normal" diploid somatic cells) and gametes (germ cells, i.e. haploid cells) with a germ line age and are mortal.

Perennial plants are an important exception here, as they are potentially immortal through vegetative reproduction. In the plant kingdom, there are a large number of species that - according to current knowledge - do not age. For example, a pedunculate oak tree that is over a thousand years old produces leaves and acorns of the same quality every year. If the tree dies, it is due to external influences such as fire or fungal attack.

Many lower organisms that do not have a germline do not age and are potentially immortal. This is also referred to as somatic immortality. These potentially immortal organisms include prokaryotes, many protozoa (e.g. amoebae and algae) and species with asexual division (e.g. multicellular organisms such as freshwater polyps (Hydra)). In fact, however, these organisms do have a limited life span. External factors, such as ecological changes or predators, significantly limit life expectancy and lead to so-called catastrophic death.

Of particular scientific interest are higher organisms that, after becoming adults, apparently do not age further and show no signs of senescence. This is referred to as "negligible senescence". Such organisms are characterized by a constant reproductive and mortality rate over age; in contrast to aging organisms, their specific mortality remains constant with increasing age. Some species are thought to have these characteristics. These include, for example, the rockfish Sebastes aleutianus (Rougheye rockfish), of which a 205-year-old specimen has been recorded, and the American pond turtle (Emydoidea blandingii). Some authors also see negligible senescence in the naked mole rat - the only mammal to date. In general, it is very difficult to prove that any higher species exhibits negligible senescence. Extremely old specimens are very rare, as no species is immune to catastrophic death. Data from captive animals are not yet available for a sufficiently long period. The postulate of negligible senescence was not established until 1990.

The jellyfish Turritopsos Nutricula is said to be able to renew its cells when vital functions decline. According to researcher Ferdinando Boero, once this state is reached, it lets itself sink to the bottom of the sea and regenerates its cell volume there. It lives without limit, unless it is killed by other animals, for example.

In non-aging organisms, the probability of death is independent of age and timing. The age-specific mortality rate, which is the number of deaths in a given age class, is therefore constant. The survival curve of non-aging organisms is a straight line in semi-logarithmic representation.

In the case of "immortal" bacteria or dividing yeasts, the daughter cells are largely identical copies of the initial cells. It is debated whether in such cases one can really speak of immortality; after all, two new individuals are created. Irrespective of this philosophical question, such cells may not show any signs of ageing: These would be transmitted to the daughter cells, accumulate (accumulate) from generation to generation, and ultimately extinguish (eliminate) the entire species. In contrast, in multicellular organisms (metazoa) and budding yeast, aging can occur in the somatic cells, or mother cells. The germ cells, which are important for the preservation of the species - in the case of yeast, daughter cells - must remain intact.

Freshwater polyps (here Hydra viridis) do not know aging and can theoretically live to any age under optimal environmental conditions.

Aging Neapolitan Mastiff

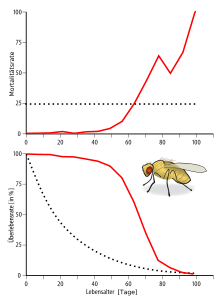

Relationship between survival rate (bottom) and mortality rate (top) using the example of a population of males of the species Drosophila melanogaster at 25 °C: The exponential increase in the mortality curve with increasing age is a characteristic of ageing. The dashed lines represent a hypothetical population with the same maximum age that does not age. The mortality curve would be a straight line: at each point in time, the probability of death would be the same.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is ageing?

A: Ageing is the many changes that happen in an individual over time. In living things, it includes most physical and psychological changes which occur after adulthood.

Q: What is senescence?

A: Senescence is the biological process which leads to ageing. It involves a gradual slowing down of cell division and growth as time goes on.

Q: Why do animals (especially humans) age?

A: There have been many attempts to answer this question, but one explanation suggests that the peak age of reproduction in mankind's history was lower than today. Any allele of a gene which interfered with reproduction would have less chance of passing on to the next generation, so natural selection would virtually eliminate any inherited effect which reduced fertility. Additionally, our cells collect damage to their DNA over time, causing us to become gradually less fit as we age.

Q: Do protists age?

A: No - they divide and the next generation is just as good as the last.

Q: How are actuarial tables used?

A: Actuarial tables show the likelihood of death at each stage of life and are used by insurance companies to assess rates for life policies and pensions.

Search within the encyclopedia