Boxer Rebellion

Boxer Rebellion

Fight between allied and Chinese troops

The Boxer Rebellion or Boxer War (Chinese 義和團運動 / 义和团运动, pinyin Yìhétuán Yùndòng - "Movement of Associations for Justice and Harmony") refers to a Chinese movement against European, US and Japanese imperialism. The Western name Boxer refers to the traditional martial arts training of the first boxers, who called themselves Yihetuan (義和團 / 义和团, Yìhétuán - "Association for Justice and Harmony") or Yihequan (義和拳 / 义和拳, Yìhéquán - "Fists of Justice and Harmony").

In the spring and summer of 1900, the attacks of the Boxer movement against foreigners and Chinese Christians brought about a war between China and the United Eight States (consisting of the German Empire, France, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, Austria-Hungary, Russia and the USA), which ended with a defeat of the Chinese and the conclusion of the so-called "Boxer Protocol" in September 1901. Since the term "Boxer Rebellion" unilaterally reflects the imperialist perspective (the Chinese government was explicitly supported by the Boxers), it is also referred to as the "Boxer War" or the Chinese term is used.

"Boxer" rebels armed with various Dao, (1900).

The Ketteler Arch was erected over the place of death

A "Boxer" (1900)

Contemporary German caricature on a postcard from 1900

Previous story

Conflicts between Christians and non-Christians arose in China already after the establishment of the first Christian communities, when Christians refused to pay local (informal) taxes, which were mainly used for religious purposes. Increasing quarrels between these opponents already led sporadically to violent confrontations. In addition, there were two wars within a short period of time in which China was attacked by Western states: The First Opium War (1839 to 1842) against Britain and the Second Opium War (1856 to 1860) against Britain and France. These wars further fueled Chinese reservations about Christian, Western foreigners.

Immediately after the uprising, Chinese authors spread the thesis that the "Boxers" were an offshoot of the rebellious White Lotus sect, which had organized a substantial uprising from 1795 to 1804. Today, the prevailing view is that the "Boxers" were a social movement formed between 1898 and 1900 as a direct reaction to the mood of crisis at the end of the 19th century. Its original focus was in Shandong Province, where it was able to tie in with already existing organizations such as the "Dadao Society", i.e. "Society of Great Sabers", (大刀會 / 大刀会, Dàdāohuì - "literally, Society of Great Knives"). In the spring and summer of 1900 it then spread over large parts of northern China.

Boxers were influenced primarily by popular culture and religion, especially by the various martial arts schools. Characteristics of the movement were:

- a loose organizational structure in which independent groups rallied around local leaders;

- Members recruited mainly from rural areas and met in small towns in the province;

- collective mass trances under the alleged influence of folk-religious gods and

- Invulnerability rituals, which were also hoped to provide protection from modern firearms.

The emergence of the boxing movement was influenced by four main factors:

- the Western imperialism of unequal treaties, through which all the larger European states as well as the USA and, since 1895, Japan too, enforced legal and economic privileges on China (especially the extraterritoriality of their nationals);

- the internal Chinese conflict between reformers and conservatives at the imperial court, which culminated in 1898 in the suppression of the Hundred Days Reform by the conservative faction around Empress Dowager Cixi;

- the special position of the Christian mission in the interior, which was likewise based on unequal treaties, where the missionaries intervened in local disputes with the help of the foreign consuls;

- the sense of crisis triggered by a series of natural disasters and subsequent famines in northern China in the late 1890s.

Whether foreign trade (imports) actually put many people out of work and thus helped trigger the Boxer Rebellion, on the other hand, is debatable.

The Boxers blamed the foreigners, secondarily the Chinese Christians, for disturbing the natural environment and social harmony. They demanded that China's enemies be eliminated by force in order to restore this harmony. In doing so, they acted as supporters of the ruling Qing (Manchu) dynasty. One of their most famous slogans was, "Support the Qing and destroy the foreigners."

Nevertheless, the imperial court tried to suppress the Boxers until the spring of 1900. Because of the Boxers' loose organizational structure, however, the attempts failed. Only when the foreigners then put massive pressure on the government in Beijing did Cixi and some of the high officialdom change their minds and begin to see the Boxers as allies against the foreigners.

Legation quarter shortly before the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion

The attack of the "Boxers" on the foreign legations

As early as January 11, 1900, Empress Dowager Cixi (obsolete: Tz'u-Hsi), the regent of China, had issued an edict proclaiming that some of the Boxers were law-abiding people. On January 27, the European colonial powers, Japan, and the United States called on the Chinese government to protect European institutions from the Boxers. Efforts to suppress the movement continued. On April 15, the Boxers were banned, but because regular imperial troops in Beijing and Tianjin (obsolete: Tientsin) allied with them, the ban could not be enforced. In May the movement reached the vicinity of the capital Beijing and began attacks against foreigners as well as against the railway lines leading to the coast. Riots claimed 73 lives on May 18 alone. The foreign envoys in Beijing then ordered some 350 soldiers to Beijing as envoy guards, who arrived there between May 31 and June 3. In the following days the Boxers intensified their attacks against Chinese Christians as well as foreign institutions and began to carry the insurrection into the city of Peking. The hatred for Chinese Christians stemmed from the fact that disputes with traditional Chinese often led Christians to turn to their European missionaries, who, through their special rights and legations, regularly decided the dispute in favor of the Christians.

The first Allied counterattack and its failure

On June 10, 1900, a 2066-man international expeditionary force under the command of British Admiral Sir Edward Hobart Seymour marched into Tianjin to protect the legations in Beijing. However, it was held up by the Boxers (14-18 June) and had to turn back. Meanwhile, the approximately 473 foreigners, 451 soldiers and over 3,000 Chinese Christians in Beijing had barricaded themselves in the legation quarter and the Xishiku Church. There they were cut off from communication with the foreign bases on the coast, because the Boxers had cut the telegraph line.

In the meantime, however, a large international fleet was gathering off the coast of China to disembark a relief army.

Faced with this situation, the Allied forces issued an ultimatum to surrender the heavily fortified Chinese coastal forts of Dagu. On June 17, 75 minutes before the ultimatum expired, the Chinese opened fire. The forts had modern artillery but little experience. Allied gunboats on the Peiho River in front of the forts returned fire, and over the next few hours the forts were stormed by the Allies despite fierce resistance.

On June 19, the imperial government issued an ultimatum to the European envoys in Peking to leave China within 24 hours. On the same day, the German marines were mobilized and sent to China. On June 20, the envoy of the German Imperial Government, Baron Clemens von Ketteler, was shot dead in Peking in the open street by a Manchurian banner soldier. Ketteler, along with his interpreter Heinrich Cordes, was on his way to the Foreign Ministry to negotiate the ultimatum in person with the heads of that office, Princes Qing and Duan. The circumstances of Ketteler's assassination have not been fully clarified to this day. There are two different versions of the course of events from those directly involved. The translator Cordes portrayed the act as a targeted assassination of Ketteler as German envoy, initiated by the Chinese government. The assassin En Hai himself testified that the murder had taken place in connection with the war order after the storming of the Dagu Fort. An order to shoot all foreigners had been issued, but there had been no direct order to kill Ketteler. The assassin En Hai was arrested two months after the crime and publicly executed by beheading. Ketteler's successor as German envoy was Alfons Mumm von Schwarzenstein.

On news of the storming of the Dagu forts, the imperial court issued an edict to its subjects on June 21 that amounted to a declaration of war on the Allies. Imperial troops were now officially fighting alongside the Boxers. Conversely, none of the Western states formally declared war on China. It is true that, even under the European-style international law of the time, storming and destroying the defences of a foreign state and marching armed men on its capital was a clear act of war. However, it was at least disputed among the Allies whether international law could be applied to China at all, since China had been represented at the Hague Peace Conference of 1899, but had not signed the Land Warfare Convention adopted there. The lack of a declaration of war placed the war in China as a "punitive expedition" on the same level as other colonial wars waged against ethnic groups ("tribes") that were not organized as states.

On 26 June Seymour had to admit defeat and retreated to Tianjin. China tried to persuade Japan to change sides and form an alliance with China on July 3, but Japan rejected this on July 13.

The war in Beijing and Tianjin

Despite the unspoken declaration of war, the war bore the character of a state war in the early stages, as regular armies fought each other, although the Chinese troops were reinforced by Boxer militias. They laid siege to the legation quarter in Beijing, where diplomats, missionaries, engineers and Chinese Christians were holed up. The British Embassy became the command centre for the 500 or so gunmen, who were faced by some 20,000 Chinese. However, the defense was organized by the individual legations, which led to disputes and weakened the defense force. At the same time, the international concession in Tianjin (Tientsin) was also besieged by the Chinese. However, there was also dissension on the Chinese side. A number of senior officials - most notably Grand Secretary Ronglu - disapproved of the conduct of the Empress Dowager, who even had several officials executed for their critical remarks. Observations that Chinese artillery fired too low, as well as unused modern guns found in Beijing after the siege, suggest that the battle was not fought with all determination by Chinese troops at the instigation of the Chinese Peace Party.

The international troops captured the city of Tianjin on July 14, 1900.

The Second International Expeditionary Force

In the meantime, six European states as well as the USA and Japan were putting together an expeditionary force for intervention in China. The German Emperor Wilhelm II had reacted immediately to the proposal of a joint military action of European states, because in this framework the increased role of the German Empire in world politics could be demonstrated. To his satisfaction, he was able to ensure that the former German Chief of Staff, Field Marshal Alfred Graf von Waldersee, was given the supreme command of this joint expeditionary army. At the farewell ceremony for part of the German troops in Bremerhaven on 27 July, Wilhelm II delivered his infamous Hun speech:

"A great task awaits you: you must atone for the grave injustice that has been done. The Chinese have overturned the law of nations; they have made a mockery of the sanctity of the Envoy, of the duties of hospitality, in a manner unheard of in the history of the world. This is all the more outrageous because this crime was committed by a nation that is proud of its ancient culture. Prove the old Prussian efficiency, show yourselves as Christians in the joyful endurance of suffering, may honour and glory follow your flags and arms, give an example to all the world in manly conduct and discipline [...] If you come before the enemy, he will be beaten. Pardon will not be given, prisoners will not be taken. Whoever falls into your hands, let him be in your hands. As a thousand years ago the Huns, under their king Etzel, made a name for themselves which even now makes them appear formidable in tradition, so may the name of Germany become known in China in such a way that never again will a Chinese dare to look even askance at a German!"

Bernhard von Bülow, Reich Chancellor Chlodwig zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst and also the director of the North German Lloyd made efforts to prevent the spread of this incendiary speech. In the long run, it coined the term the Huns (used mainly in England) for the Germans, which was to play a role especially in propaganda during the First World War.

The troops embarked from Europe, however, arrived too late to participate in the relief of Tianjin and Beijing. The 20,000-strong Allied force that left Tianjin on August 4 consisted primarily of British-Indian, Russian, Japanese, and U.S. troops (the latter had been transferred to China from the Philippines); the Germans, French, Austrians, and Italians participated only with a few detachments of marines.

The expeditionary force reached Peking on 13 August 1900, which fell the very next day. On August 15, the empress dowager and her council fled Beijing for Xi'an/Shaanxi, embarking on an "inspection tour". Beijing was sacked by the Allies for three days, which - given the Europeans' high standards of civilization - alienated critics. Cultural goods were also looted.

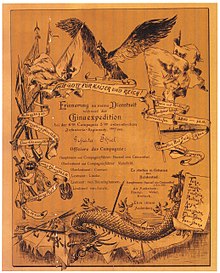

A document on the occasion of the China expedition of the 6th Company of the 3rd East Asian Infantry Regiment gives a vivid overview of the chronological course of the expedition. Departure with the steamer "Rhein und Palatia" from Bremerhaven on August 2, 1900. Voyage to China via Gibraltar, Port Said (Suez Canal), Aden, Colombo, Singapore. Then the places in China: Peitang on 20 September 1900; Yung-Shing-Shien on 15 December 1900; Chou-Chouang 24 December 1900; Kwang-Tshang on 20 February 1901; Tshang-Tshöng-Puss on 8 March 1901; Huolu on 24 April 1901. In addition, there were military engagements at Taku, Tangku, Tianjin, Pautingfu, Ansu, Tien-Shien, Tsho-Tshou, Jau-Shane. The return was to Bremerhaven on 9 August 1901.

The Boxer Rebellion after the capture of Beijing

After the capture of Beijing, the character of the war changed. In an edict of September 7, Cixi blamed the Boxers for the military defeat and ordered the provincial governors to again use government troops against them. On September 25, high officials involved in the uprising were demoted by the imperial court. At the same time, Allied troops began conducting "punitive expeditions" against "boxer's nests," thus breaking the last resistance. In their operations, the Allied troops indulged in brutal outrages against the Chinese population (murders, looting, rapes). Their aim was to spread terror and thereby deter the Chinese from a future uprising against the foreigners. However, the deployment of troops was limited to the northern Chinese province of Zhili, since the provincial governors of central and southern China concluded standstill agreements with the foreigners.

A total of 231 foreigners, including about 200 missionaries, and about 32,000 Christian Chinese fell victim to the Boxers. The missionaries were mainly killed in the cities of Taiyuan and Baoding at the instigation of Governor Yuxian. In all, about 100,000 civilians were killed by the Boxers. About 5000 civilians were killed by the Allied warfare. 1003 foreign soldiers fell, mostly Japanese and Russians. On the Chinese military side, there were about 2000 casualties. The number of boxers killed is not known.

Document for the military expedition to China (1900)

The troops of the united eight interventionist states in a Japanese drawing (Germany is shown at the top center).

"The Germans to the front!" 22 June 1900 - German troops on contemporary postcard

Soldiers of the German 1st East Asiatic Infantry Regiment with the flags captured during the storming of the Peitangforts

Theodor Rocholl: Battle for the Ho-phu Mountain Fortress (January 3, 1901)

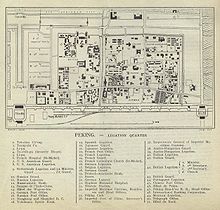

The legations' quarters in Peking, 1912

Foreign troops in the Forbidden City in Beijing

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Boxer Rebellion?

A: The Boxer Rebellion was an uprising that took place in China from 1900 to 1901.

Q: Who led the Boxer Rebellion?

A: The Boxer Rebellion was led by a group of Chinese citizens known as the Boxers.

Q: Why did the Boxers rebel?

A: The Boxers rebelled because they were unhappy with the large amount of foreign influence within China.

Q: When did the Boxer Rebellion take place?

A: The Boxer Rebellion took place from November 1900 to September 1901.

Q: What was the outcome of the Boxer Rebellion?

A: The Boxers were eventually defeated by a coalition of foreign powers, which led to increased foreign influence within China.

Q: Who were the foreign powers involved in the Boxer Rebellion?

A: The foreign powers involved in the Boxer Rebellion included Britain, France, Germany, Japan, and the United States.

Q: What impact did the Boxer Rebellion have on China?

A: The Boxer Rebellion led to increased foreign influence within China and weakened the Qing dynasty, which would eventually collapse in 1911.

Search within the encyclopedia