Bovidae

The hornbearers (Bovidae) or bovids are a family of ruminants, which in turn belong to the cloven-hoofed animals. They currently form the most species- and form-rich group within the cloven-hoofed and hoofed animals and include, among others, the cattle, sheep, goats and various forms of antelope. The family occurs naturally in Eurasia as well as in Africa and North America. Domesticated forms also reached Australia and South America. Hornbills are very common in open landscapes, and many species also inhabit forests and wetlands as well as rocky landscapes. Depending on the type of landscape, different social systems have developed, ranging from territorially solitary, often site-faithful animals to large, roaming herds. Reproduction is therefore dependent on the lifestyle of the individual species. There are monogamous pairings as well as polygynous reproduction strategies. Overall, hornbearers feed on a variety of plants, from hard grasses to soft leaves and fruits, occasionally eating animal remains.

In general, two large groups of forms can be distinguished within the horn bearers. The cattle, buffaloes and kudus belong to one, the goats, sheep, antelopes and gazelles to the other. This dichotomy was already noticed at the beginning of the 20th century, but the history of research on the hornbearers as a unified group goes back to the first half of the 19th century. In the past, the exact systematic classification of the group was the subject of numerous debates, only molecular genetic analysis methods, which emerged towards the end of the 20th century, gave a coherent picture. Not without controversy is a 2011 revision of the family that resulted in a doubling of the number of current species. This reconsideration of the hornbearers was met with opposition in some quarters, but also found supporters on several occasions who considered it necessary. From a phylogenetic point of view, hornbearers are relatively young. The oldest records date to the Lower Miocene, about 18 million years ago.

Features

Habitus

Altogether, about 280 species belong to this family, whose range of variation reaches from the smallest buck (Neotragus pygmaeus) with a head-torso-length of about 40 cm and a weight of 2 kg to the huge bison (Bos bison) with a body length of 380 cm and a weight of 1000 kg. The external characteristic of all species are the horns, of which there are almost always two in number (an exception is the four-horned antelope, among the domesticated forms the Jacob's sheep also has four horns) and which are species-specific in their shape. As an extremely shape-rich group, horned antelope have evolved a relatively variable physique that is adapted to the particular landscape conditions. Open-land species tend to be larger than inhabitants of closed landscapes and also possess larger and longer horns. Sexual dimorphism is more developed in herd-forming species than in solitary ones. Open-land animals also often have longer bodies and slender limbs with fore and hind legs of approximately equal development, which can be interpreted as an adaptation to rapid locomotion. In woodland animals, the hind legs are generally more developed and the forelegs much shorter, giving the croup an elevated position. In addition, their body is generally shorter, which is due to the more confined space in forests. The coat coloration appears variable from drab brown to single spots and stripes, which often have a camouflaging character. The tail can be short and flat, but also long and round with a tuft-like end. Throat pouches appear in many species, and some have a nose leather.

Horns

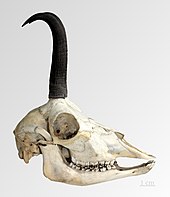

The horns, whose length varies from 2 cm with the Kleinstböckchen to over 1,50 m with the saber-antelope (Oryx dammah) or the giant-elk-antelope (Taurotragus derbianus), are trained with some types only with the males, with most however with both sexes, with what those of the females then are often smaller and less powerfully built. The reasons for the development of horns in females are not fully understood, but are thought to be defence against predators, competition for food, or a camouflage effect in intraspecific competition to simulate a male. Since horned females are more common in large and conspicuous species of open country and less common in forms with camouflaged coats that live hidden in the forest, protection from predators is thought to be one of the driving factors, according to some studies. Horns are bony outgrowths of the skull, composed internally of spongy substance or cavities, with a rough edge at the lower margin. They arise from an ossification center in the skin (os cornu) and grow from the bottom upward, forming the typical pointed structure of horns. In most species the single horn is connected to the frontal bone by a short bony peg (pedicle), exceptions are some representatives of the duiker (Cephalophus) as well as the four-horned antelope (Tetracerus quadricornis) and the Nile antelope (Boselaphus tragocamelus). The cone never reaches the dimensions of the bony horn, but always remains thinner than it. The horns are surrounded by a sheath of horn (keratin), which is hollow on the inside (which gave the horn-bearers the old name "cavicornia" ("hollow horns"), among other things). The covering attaches to the lower edge of the bony horn and always overhangs it, growing from the inside out. Unlike deer and pronghorns, the frontal arms of hornbearers are never branched; moreover, the horns are not shed annually as in the antlers of deer, nor is the horn sheath subject to seasonal renewal as in pronghorns. Rather, they grow for a lifetime and do not regenerate when damaged or broken. The horns are sometimes almost straight, as in the klipspringers (Oreotragus), or curved, as in the bison (Bos bonasus), or twisted and curved in many ways. In some species they can be rotated clockwise (homonymous or inverse) or counterclockwise (heteronymous or normal) (in relation to the right horn). On the one hand, such torsions occur along the longitudinal axis of the horns, for example in the eland (Taurotragus oryx), without affecting their straight course; on the other hand, they also occur in curved horns, as in the impala (Aepyceros melampus), or form open spirals, for example in the Cape greater kudu (Strepsiceros strepsiceros). In any case, the coils are formed by different growth rates in the horn sheaths.

Skeletal features

Further characteristic features are found in the dentition and skeletal structure. The dentition lacks the upper incisors, the upper canine and the first premolar in the upper and lower jaw. Only some early forms, now extinct, still possessed a small upper canine; enlarged canines, such as occur in some deer and in the musk deer, were never developed in horn-bearers. The lower canine resembles incisors (incisiform). The standardized tooth formula of hornbearers is:

Skeleton of a Ducker (Cephalophini)

Skull of the Pyrenean chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica)

Horns of different horn bearers

Southern helleborine (Tragelaphus sylvaticus) as inhabitant of closed landscapes

.jpg)

Southern hartebeest (Alcelaphus caama) as inhabitant of open landscapes

Distribution

Hornbearers occur naturally in Eurasia and Africa, as well as in North America; there have never been wild hornbearers in South America, nor in Australia. Domesticated species, however, have been introduced into nearly all countries. The landscapes used by hornbearers vary considerably, depending on the requirements of the species, and are distributed from sea level to mountainous locations and highlands around 6000 m. Most hornbearers inhabit open terrain. Thus, the African savannahs as well as the rocky mountains of Asia each offer an ideal habitat to numerous species. Other representatives are found in desert-like regions, more temperate steppes and grasslands, in the forest or in wetlands. Many species prefer undisturbed landscapes, while others can cope with more human-influenced areas.

American bison (Bos bison)

Questions and Answers

Q: What are Bovids?

A: Bovids are a family of even-toed ungulate mammals.

Q: Where does the word "Bovidae" come from?

A: The word "Bovidae" comes from Latin bos, "ox".

Q: What is a unique characteristic of even-toed ungulates?

A: Even-toed ungulates have "cloven hooves": that means their hooves are formed from two toes.

Q: How many species are in the Bovidae family?

A: There are 143 living species in the Bovidae family.

Q: What are some examples of animals in the Bovidae family?

A: Some examples of animals in the Bovidae family include cattle, goats, sheep and antelopes.

Q: What is a unique characteristic of Bovids' digestive systems?

A: Bovids are all ruminants, with the double stomach system of digesting vegetation, which is most efficient.

Q: What is the reason for the success of the Bovids family?

A: The success of the Bovids is probably helped by their digestive system.

Search within the encyclopedia