Bordeaux

![]() Map with all coordinates: OSM | WikiMap

Map with all coordinates: OSM | WikiMap

![]()

This article is about the city in the southwest of France. For other meanings, see Bordeaux (disambiguation).

Template:Infobox commune in France/maintenance/alternate coat of arms in Wikidata

Bordeaux [bɔʀˈdo]; French![]() ; (Occitan Bordèu) is a university city and the political, economic, and scientific center of southwestern France.

; (Occitan Bordèu) is a university city and the political, economic, and scientific center of southwestern France.

Its inhabitants call themselves Bordelais. The city is famous for its Bordeaux wine and cuisine, but also for its architectural and cultural heritage. Bordeaux is the seat of the prefecture of the Gironde department and the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the seat of an archbishop and a German consulate general. The city has a reputation as the secret capital of France due to the many museums located there and the fact that during Germany's invasions of France in 1870/71, 1914, 1940, the seat of government was periodically moved from Paris to Bordeaux.

Bordeaux itself has 257,068 inhabitants (as of 1 January 2018). However, the Bordeaux agglomeration has about 773,542 inhabitants and also includes 26 surrounding municipalities organized in the Bordeaux Métropole. The area is 578.3 km² and the population density is 1338 inhabitants/km². This federation is in turn part of an agglomeration (Aire urbaine de Bordeaux), which includes the wider catchment area with a total of 51 municipalities, thus coming to 1,215,769 inhabitants living on 5,613.4 km², which corresponds to a population density of 216 inhabitants/km². Bordeaux is thus the largest city in the Gironde department and the Aquitaine region, and the ninth largest city in France. The agglomeration ranks sixth in France. The arrondissement of the same name is also administered from Bordeaux, which consists of 21 cantons.

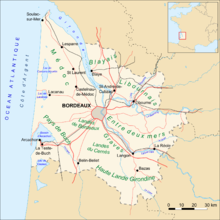

Bordeaux in the Gironde department

Geography

Bordeaux is a city located in the southwest of France, about 45 kilometers from the Atlantic Ocean on the Garonne River, which runs in a wide arc through the city. This shape of a crescent moon helped the city get its name Port de la lune (Port of the Moon). A few kilometres downstream, the Garonne joins the Dordogne to form the Gironde estuary, which is over 70 kilometres long. Tidal forces can therefore be observed right into the city area. At high tide, the inflowing seawater pushes the river back and raises the level by about four to five metres. The resulting currents create eddies and turbulent surface water. At times, a veritable wave can move upstream for dozens of kilometres. This phenomenon is called mascaret (spring tide) in Bordeaux.

Geology

The left bank of the Garonne, on which by far the largest part of the urban area is located, consists of wide, marshy plains from which low hills rise. These are made up of boulder sediments and for the most part have gravel and crushed stone as subsoil. The soils are poor, but excellent for viticulture due to their water permeability and ability to retain heat. The city of Bordeaux lies between the downstream Médoc and the upstream Graves area, which are geomorphologically very similar. Famous wineries are not uncommon right into the heavily urbanized metropolitan area.

The right bank merges almost immediately into a limestone plateau up to 90 meters high, so that there is a striking escarpment there. The plateau is home to world-famous wine-growing regions such as Saint-Émilion, Pomerol and Fronsac, where some of the most expensive wines in the world are cultivated.

Climate

Bordeaux lies on the southern edge of the temperate climate zone. The very mild winters and the long, warm summers already allow subtropical-Mediterranean influence to be felt. Precipitation is frequent in all seasons; with a rainfall of over 900 millimeters per year, relatively high amounts are achieved by French standards. This falls mainly in the winter half of the year, in summer more in the form of heat thunderstorms. The highest amount of precipitation ever measured in France within half an hour was reported from Bordeaux in July 1883. Enormous damage was also caused by a "double thunderstorm" in 1982, when on 31 May the entire monthly rainfall was recorded within one hour, and three days later another half an hour within 50 minutes.

The annual mean temperature is about 12.8 °C with an average minimum of 5.9 °C in January and a maximum of 20.2 °C in July. The temporally shifted temperature maxima are due to the oceanic climate. Despite the balanced temperature cycle, extreme temperatures can occur in appropriate weather conditions: During the heat wave of 2003, the maximum values reached at least 35 °C on twelve consecutive days, including 41 °C on one day.

The city has a high level of sunshine. With about 2,000 hours of sunshine per year, Bordeaux surpasses most French regions, with the exception of the Mediterranean and some coastal areas on the Atlantic.

The microclimates of Bordeaux and its surroundings are one of the decisive factors for the excellent winegrowing conditions: The city and surrounding growing areas are protected from the sea winds by a wide strip of pine forest (Forêt des Landes). In addition, the Gironde provides a temperature-balancing effect, as this body of water releases heat stored during the day at night and also reflects solar radiation over a wide area into the surrounding countryside.

| Bordeaux | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monthly average temperatures and precipitation for Bordeaux

Source: wetterkontor.de | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

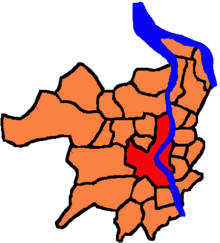

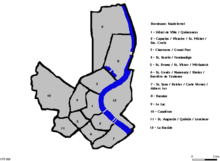

Neighborhood

Bordeaux is administratively divided into eight urban arrondissements. The arrondissements 1 to 6 are located on the left bank of the Garonne and are numbered from north to south, the seventh is the right bank of the Garonne and the eighth is the incorporated district of Caudéran. Since the historically grown was mostly not taken into account, this has led to the fact that the inhabitants do not identify themselves with their arrondissements - as for example in Paris. Instead, it is customary to indicate residence by neighborhoods or districts. Usually, these also give some indication of the standard of living.

Vieux Bordeaux (Old Town)

Since 2007, the old town of Bordeaux has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site under the designation Historic Centre of Bordeaux ("Port of the Moon"). The area inside the former city walls is the historic core of Bordeaux. It is bounded by the ring-shaped structure of the main streets and the banks of the Garonne, and divided by two main axes:

From north to south, the Rue Sainte-Catherine, over a kilometre long and today completely converted into a pedestrian zone, runs from the Place du Grand Théâtre to the Place de la Victoire, where the old university buildings stand. Here and to the west is the business district of Bordeaux with a focus on commerce and services, to the east as far as the Garonne, residential development predominates - some of it very old.

The east-west axis is formed by the Pont de pierre, the only bridge crossing within the historic centre. Its continuation is the Cours Victor Hugo. To the north, residential and commercial areas of high to very high standards predominate, to the south simple locations.

In the north-western part, in the Quinconces and Hôtel de Ville districts, you will find fine restaurants and cafés, prestigious branches of banks and financial service providers, cinemas and retail outlets for upmarket or luxury needs. Here lies the Triangle d'or (Golden Triangle), as it was known in the days of the Intendants, an almost equilateral triangle formed by three avenues and considered the showcase of fine Bordeaux. In the north-eastern part in the Saint-Pierre and Saint-Eloi neighbourhoods are restaurants, hotels and pubs. The original alternative charm is slowly giving way to a certain chic. The south-western part in the Victoire neighbourhood is strongly student-oriented, but also a preferred place to live for the middle class. In the southeast, in the Capucins, Saint-Michel and Sainte-Croix neighbourhoods, low-income groups predominate, including the elderly, workers, the unemployed and immigrants.

The former faubourgs (suburbs)

The residential belt between the Cours and the Boulevard developed from former suburbs outside the city walls and is, with exceptions, similarly structured: In the north preferred, in the south simple locations predominate.

Along the Garonne to the north are the Chartrons and Grand Parc districts, the former the home of many wine merchants and bourgeois in character, the latter a large housing estate for low-income classes.

The northwest around the Palais Gallien is home to the Saint-Seurin district, an upscale residential area and home to many consulates.

To the west rises the Mériadeck shopping and administrative centre, the only high-rise ensemble in the city centre. For its construction, large areas of simple quarters were demolished, the condition of which was considered dilapidated and unhygienic. Although high-quality residential development was planned between the commercial and administrative areas, there has been no increased settlement of the upper classes; on the contrary, the buildings have already taken on a slight patina. On the contrary, the buildings have already begun to show a slight patina. However, the generous transport infrastructure has led to the establishment of a number of hotels of a higher standard. Around Mériadeck, the original development for the lower to middle class has been preserved, consisting mostly of one- to two-storey rows of houses with small gardens. These so-called échoppes are very popular with the population today.

Saint Genès in the southwest has an upper middle-class character, while the station district in the south is still a residential area for the poor. Industry and commerce, railway lines and unappealing infrastructure such as the central slaughterhouses characterize the picture.

After decades of neglect, the right bank of the Garonne has come to the attention of urban planners. In place of the industrial and railway districts of Bastide and Benauge, a completely new residential district for the upper classes is being built directly opposite the old town. This is being done mainly in La Bastide on the southern area of the former railway and goods station site and the adjoining industrial estates. This began with the conversion of the old Gare d'Orléans station into a multiplex cinema and the opening of the Jardin botanique de Bordeaux botanical garden in 2003.

On the other side of the boulevard, to the north, lies the Lac district, with no residential development to speak of, and Bacalan, traditionally a dockworkers' district and now heavily marked by unemployment. To the west is Caudéran, a suburb that was incorporated in 1964, with loose buildings and a few prestigious villas. Here is located the Parc Bordelais, the largest public green space in the city. To the southwest is Saint-Augustin, a middle- to upper-middle-class neighborhood; here are the Stade Chaban-Delmas stadium and the Central Hospital.

Agglomeration

As in almost all French conurbations, the core city of Bordeaux is surrounded by a belt of independent municipalities that have grown inseparably together with it but have not been incorporated. While Bordeaux has lost population overall in the 20th century, these suburbs have grown in some cases to ten times their original population. The expansion of the agglomeration in terms of area is particularly remarkable on the left bank of the Garonne: for decades, the city has been literally eating into the surrounding pine forest, constantly pushing a belt of currently preferred peripheral residential areas in front of it. The almost consistently low buildings also contribute to the consumption of land.

The high-density part of the conurbation lies roughly within the ring road. The intersections between the ring-shaped boulevard and the arterial roads are the so-called barrières. Far from forming clear boundaries between Bordeaux and the suburbs, these have, on the contrary, become small secondary centres of the city centre due to their traffic situation, one half of which is located in Bordeaux, the other partly already in the neighbouring municipalities, which also each have their own city centres. These towns have populations of between 10,000 and 70,000 inhabitants.

Outside these cities or beyond the motorway ring road, the development becomes looser, the population density lower and the average income of the inhabitants higher. A few large facilities such as airports and industrial settlements break up the uniform picture. The municipalities located in this outer belt register between 5,000 and 25,000 inhabitants. On the opposite side of the Garonne, the transition is abrupt due to the smaller amount of space available. While near the city limits in Lormont and Cenon there are high-rise buildings on a large scale, immediately to the east the rural area already begins.

flora and fauna

Almost 90 % of the urban area has been densified to such an extent that there is no space left for natural habitats. Here, vegetation is limited to parks, green strips and empty building land. The fauna also exists only to the extent that it can adapt to almost completely built-up areas. Bordeaux in particular has a massive problem with its rat population, which the city administration has been combating for years by improving waste disposal and tighter control of catering establishments.

Near-natural space is found in the extreme north of the urban area and sporadically on the banks of the Garonne opposite the old town. Particularly in the north, which has been designated as a recreational area, some areas have been deliberately left uncultivated, so that flora and fauna typical of the Gironde still exist here: a number of migratory birds have their resting places here, some species of small game can be found in the woods and wetland dwellers (amphibians, etc.) can also be found in marshy areas.

The vineyards are a biotope in their own right, although they have disappeared from the Bordeaux urban area. In some neighbouring towns such as Pessac or Villenave-d'Ornon, however, vines are cultivated. Here, partridges and rabbits as well as their predators (birds of prey, etc.) have their habitats. The aquatic habitat is relatively undisturbed. In the Garonne exists a variety of organisms that have adapted to conditions in brackish water reservoirs, see Gironde. The artificially created lakes are mainly inhabited by ornamental or angler fish.

Pavé des Chartrons, former seat of many wine merchants and upper middle-class residential quarter

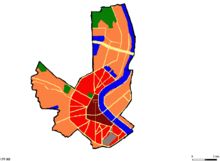

Urban structure of Bordeaux. dark red: old town; light red: inside boulevard; orange: outer districts

Town houses in the Hôtel de Ville quarter, in the background the north portal of the cathedral

Mériadeck, new district built in the seventies

The Bordeaux Métropole. red: Bordeaux; orange: member municipalities

Bordeaux district

History

→ Main article: History of the city of Bordeaux

The history of Bordeaux spans a period of almost 2300 years. It is marked by Celts, Romans, Franks and the English-French contrast. Since the middle of the 15th century, Bordeaux has belonged to France without interruption. Over the centuries, the city achieved three periods of economic prosperity, mainly due to the strategic location of its trade and transport links.

Ancient

The city dates back to a Celtic settlement from the 3rd century BC, which was called Burdigala under the Romans and became the capital of the province of Aquitania. It was at this time that Bordeaux experienced its first period of prosperity, which lasted for several hundred years; both the viticulture already practised at that time and the favourable location as a seaport were the reason for this. As the immediate surrounding countryside was marshy - the Aquitanian word burd means swamp - and infested with malaria and therefore seemed unsuitable for settlement, Bordeaux is an example of a city founded for purely strategic reasons. The Via Aquitania connected Bordeaux with Narbonne via Toulouse, the older Via Agrippa linked the city with Lyon and from there with the centres of Augusta Treverorum, Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium and Massilia.

The cityscape of ancient Burdigala must have been impressive; travelogues by Roman writers described it as a rich, magnificent city. Even during the decline of Western Rome, the city was able to maintain a certain standard of living within its fortifications before a series of lootings and devastations resulting from the migration of the peoples put an end to its prosperity.

Medieval

In the 5th century, Bordeaux was taken by the Visigoths, shortly afterwards by the Franks. At the latest after the division of the partial empire of Charibert I. of Paris, thus 567, Bordeaux belonged to Neustria. After the marriage of the Neustrian king Chilperich I, however, he gave the city, together with Cahors, Limoges, Bearn and Bigorre as a morning gift to his bride Gailswintha. These five cities were strategically located to the territory of his father-in-law Athanagild, king of the Visigoths. After Chilperich had arranged for the murder of his wife, this inheritance passed to the kingdom of Austrasia, according to a ruling of a Malberg convened by Guntram, king of the Burgundians. Ultimately disagreeing with this, Chilperich, with his son Clovis as commander, attempted to reconquer the cities in 573. Although the conquest of Bordeaux succeeded for a short time, Clovis' troops were driven out again by the Austrasian Margrave Sigulf only one month later.

In 732, Abd ar-Rahman devastated the city during his campaign. After the defeat of the Arabs at Poitiers, they were pushed back behind the Pyrenees, but in the 9th century the Normans invaded and plundered the city again. Only after this did Bordeaux begin to recover. A turning point occurred when Eleanor of Aquitaine made the French southwest an English fief by marrying Henry II. From the 12th to the 15th century, Bordeaux remained under the rule of the kings of England and experienced a second economic flourishing. The city was provided with a new city wall and the Romanesque church was replaced by a Gothic building, the Saint-André Cathedral. Bordeaux was the seat of an archbishop and the capital of the principality of Guyenne, the English adaptation of the French term Aquitaine.

From 1462 to 1790, Bordeaux was the seat of the parlement de Bordeaux, which had jurisdiction over Aquitaine and exercised legislative, judicial and executive powers there on behalf of the Crown. In particular, as a court of appeal, it decided all civil cases (by written procedure) and all criminal cases (by oral procedure) in the last instance. For centuries, the parlement de Bordeaux competed with the parlement de Toulouse, mostly over disputes of jurisdiction and priority.

Compared to other French provinces, the standard of living in Bordeaux and the surrounding area was high. The food supply was sufficient and the city benefited from a trade network through which the local wine could be exported and English manufactured goods imported. During the Hundred Years' War, the English were able to hold on in Bordeaux, and it was only after the Battle of Castillon that they had to finally vacate the Guyenne. On October 19, 1453, the troops of Charles VII entered the city. The return to France was by no means welcomed by the citizens, many of them powerful and wealthy merchants, as it meant the loss of their previous markets in England. The king also secured himself by having two large fortresses built, the Château de la Trompette in the north and the Château du Hâ in the west. These were mainly defensive structures, but the guns could also be turned against the population in the event of revolts. In 1441, the University of Bordeaux was founded.

Modern Times

From absolutism to the 20th century

After an intermittent decline, Bordeaux experienced its third heyday in the 18th century due to the flourishing Atlantic maritime trade, especially with the Antilles. At this time, some capable intendants were sent to the city, who gave it a completely new face. The Marquis de Tourny, in particular, did considerable work here. The old city walls were demolished and replaced by wide boulevards, the so-called Cours. Along these Cours, some of the most impressive private houses were built that still today partly appear as palaces. The magnificent buildings on the edge of the harbour quays also date from this period. The Grand Théâtre, built in the neoclassical style, welcomed the most sought-after ensembles from all over France. A masterpiece of mercantile architecture, the Palais de la Bourse is the seat of the Stock Exchange. This transformation of Bordeaux in the spirit of enlightened absolutism impressed the young Georges-Eugène Haussmann and may have partly become a model for the transformation of Paris under Napoleon III.

At the time of the French Revolution, Bordeaux became the capital of the Gironde department. In the National Assembly, the deputies called Girondins constituted a significant group that initially had considerable influence and was instrumental in the declaration of human and civil rights and the new constitution. These Girondins were politically aligned with the Liberals. However, they lost their influence with the reign of terror of the Jacobins around Maximilien de Robespierre in 1793/94 and were persecuted. A century later, the Monument aux Girondins was dedicated to them on the Place des Quinconces. The economic situation in Bordeaux also deteriorated again.

During the Napoleonic wars, huge contingents were moved towards Spain, passing through Bordeaux among other places. It was thanks to this that the first fixed bridge over the Garonne, the Pont de pierre, was built in 1822. The concerns of local officials about not being able to master the technical challenges in the face of strong currents and unpredictable floods is said to have led Napoleon to say "Impossible n'est pas français!" (Impossible is not French! ).

During this period, despite economic difficulties, the population grew considerably. New suburbs sprang up between the Cours and the new city boundary, today's boulevard, which has partly remained the city boundary to this day, spreading out on the left bank of the Garonne in a ring around the medieval core. To the northwest and southwest were the districts of the upper middle classes, in between the simple residential areas for workers and the petty bourgeoisie. The right bank of the Garonne developed only slowly in comparison. During the emerging industrialization, most of the large companies settled here and in the port area. Bordeaux began to grow together with its neighbouring towns.

Since the 20th century

In 1870/71, as well as during the First and Second World Wars, the French government retreated from Paris to Bordeaux to escape the advancing German troops. From 1 July 1940 to 27 August 1944, Bordeaux was occupied by troops of the German Wehrmacht, who established an important submarine port here and maintained a naval hospital from 1942. Despite this fact and its exposed location near the Atlantic coast, which the Germans developed into the "Atlantic Wall" and fortified with bunkers along its entire length, Bordeaux remained almost undamaged. The oil refinery facilities to the north of Bordeaux were bombed from the air in August 1940.

During this period, the city was a stronghold of the Resistance, as was the entire French southwest. On 21 October 1941, the war administrator Hans Gottfried Reimers was killed by the resistance fighter Pierre Rebière. The day before, an assassination attempt had been made on the field commander Karl Hotz in Nantes. As a result, 48 hostages were shot by the German occupying forces in Nantes on 22 October 1941 and 50 prisoners in Bordeaux on 24 October 1941.

Maurice Papon, the secretary of the Prefect of Gironde, Sabatier, who collaborated with the National Socialists, tried to suppress the Résistance by cruel means. For his arbitrary rule and his complicity in the Holocaust - he was responsible for the deportation of the Bordelais Jews - he was only tried in Bordeaux in 1997 as one of the last representatives of the collaboration. Jacques Chaban-Delmas, one of the most important figures of the resistance against the German occupation, was elected mayor after the war and held this post for almost fifty years.

After the Normandy invasion in June 1944, Hitler ordered the destruction of the port facilities and the Pont de pierre bridge in Bordeaux, built under Napoleon Bonaparte, if German troops withdrew from Bordeaux. However, contrary to the order, the division commander Lieutenant General Albin Nake, after negotiations with the representatives of the local Resistance, concluded a secret agreement that the city of Bordeaux would not be destroyed if the German troops withdrawing without a fight were not attacked by the Resistance groups, but were given free passage. On 22 August 1944, the German sergeant Heinz Stahlschmidt had blown up the German ammunition depot with the 4000 detonators ready for the intended demolition, killing several German soldiers. Whether this act of sabotage prevented the destruction of the city is not clear, as German troops still had enough artillery to destroy the city afterwards. Both sides adhered to the agreement made, so that the destruction of Bordeaux did not take place, combat measures were avoided, and the German troops and civilian forces were able to leave in three marching groups.

In the second half of the 20th century, Bordeaux underwent a profound structural change. The seaport, until then located directly in the city, was abandoned and replaced by a terminal near Le Verdon-sur-Mer at the mouth of the Gironde, which has the necessary water depth and capacity to handle container ships. The oil tankers serve a newly built large refinery at Pauillac, about 50 km away. After the May riots of 1968, the University of Bordeaux was moved to a new campus in the suburb of Talence to keep students at a physical distance. To the north, a fairground, hotels and shopping centres were built on previously derelict land. An administrative city was built near the city center, for which an entire neighborhood was demolished. In addition, a motorway ring was built to cope with the increasing traffic problems. In the 1970s, Ford, IBM, Siemens and Aérospatiale, among others, settled in newly designated areas on the outskirts of the city and in neighbouring communities.

Not every one of these brute measures did justice to the effort, but the decline of the economy was halted. This was also made possible by the merger of Bordeaux and its neighbouring municipalities to form Bordeaux Métropole, a municipal association that regulates inter-municipal tasks such as structural policy, local transport and supply and disposal.

During the 1990s, Bordeaux became fully aware of its historical heritage. The old town, which has retained almost all of its historic appearance, was increasingly traffic-calmed and the residential areas upgraded. Historic buildings were renovated, the frontage to the Garonne was restored and new buildings such as the Cité Mondiale du Vin were carefully integrated into the cityscape. In 1994, a large-scale urban redevelopment project was unveiled with the main aim of reuniting the city with the Garonne. Old warehouses were demolished, cycle paths and promenades were built and the industrial wastelands on the right bank of the Garonne were given new, high-quality development. In 2004, the tramway, which had been replaced by buses since the 1960s, was reintroduced with three new lines. Efforts to preserve and gently modernise the old core were rewarded in 2007 with the inclusion of the old town in the UNESCO World Heritage List.

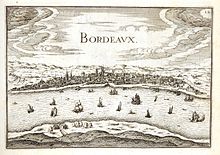

View of Bordeaux around 1634 with the Garonne in the foreground: Illustration from an atlas by Christophe Tassin

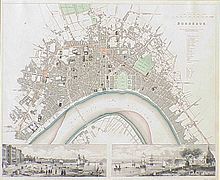

Bordeaux according to a plan of 1840 looking west. The development has already extended far beyond the medieval boundaries (marked in red). The preferred residential area is the quarter around the Jardin Public.

City view of Bordeaux after a coloured engraving from about 1850. In front right the terraces of the Place des Quinconces are visible.

Questions and Answers

Q: Where is Bordeaux located?

A: Bordeaux is located in the Gironde department of France.

Q: What is the population of the area around Bordeaux?

A: About 1,150,000 people live in the area around Bordeaux.

Q: What kind of climate does Bordeaux have?

A: Bordeaux has a temperate oceanic climate (Cfb in the Koeppen climate classification).

Q: What is Bordeaux famous for?

A: Bordeaux is famous for wines made in the region near the city and for its art.

Q: What is the classification of Bordeaux?

A: Bordeaux is classified as a "City of Art and History".

Q: How many monuments historiques are located in Bordeaux?

A: Bordeaux is home to 362 monuments historiques.

Q: Is Bordeaux a UNESCO World Heritage Site?

A: Yes, Bordeaux is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Search within the encyclopedia