African bush elephant

The African elephant (Loxodonta africana), also African steppe elephant or African bush elephant, is a species of the elephant family. It is the largest land mammal currently living and also the largest recent land-dwelling animal on Earth. In addition to its tusks and distinctive trunk, its outstanding characteristics are its large ears and columnar legs. In numerous morphological and anatomical characteristics, the African elephant differs from its somewhat smaller relatives, the forest elephant and the Asian elephant. Its range now covers large parts of sub-Saharan Africa. There, the animals have adapted to numerous different habitats, ranging from closed forests and open savannah landscapes to swamps and desert-like regions. Overall, however, the occurrence is highly fragmented.

The way of life of the African elephant is well researched through intensive studies. It is characterized by a strongly social character. Females and their offspring live in family groups (herds). These in turn form a more closely related clan. The individual herds meet on certain occasions and then separate again. The males form bachelor groups. The different associations use action areas, in which they partly move around in the annual cycle. For communication among each other the animals use different sounds in the low frequency range. By means of their vocalizations, but also by certain chemical signals, the individuals can recognize each other. In addition, there is an extensive repertoire of gestures. The cognitive abilities of the African elephant should also be emphasized.

The diet consists of both soft and hard plant food. The composition varies regionally and seasonally. In general, the African elephant spends a large part of its daytime activities feeding. Breeding occurs year-round, but regionally there are tendencies toward greater seasonalization. Bulls enter musth once a year, during which they go on migration in search of cows willing to reproduce. During musth, aggression is increased and rivalry fights take place. The sexual cycle of the cows lasts comparatively long and shows a course untypical for mammals. After birth, it usually stops for several years. Usually after almost two years of gestation a young animal is born, which grows up in the maternal herd. Young female animals remain later in the herd, the young males leave it.

The first scientific description of the African elephant took place in 1797 with a formal species separation of the African from the Asian elephant. The genus name Loxodonta in use today was not officially introduced until thirty years later. The name refers to striking differences in teeth between the Asian and African elephants. During the 20th century, several subspecies were distinguished, including the forest elephant of central Africa. The latter is now considered a separate species according to genetic studies, the other subspecies are not recognized. The African elephant was first recorded in the early Middle Pleistocene. The total population is considered to be highly endangered. The main reasons for this are hunting for ivory and habitat loss due to the increasing human population. The African elephant is one of the so-called "Big Five" of big game hunting and safari.

Features

Habitus

The African elephant is the largest living land mammal and is relatively easy to recognise by its trunk, tusks, large ears and columnar legs. The head-torso length is 600 to 750 cm, and the tail grows another 100 to 150 cm long. A fully grown bull has a shoulder height of 290 to 370 cm, according to studies in Amboseli National Park. Cows are on average smaller, measuring 250 to 300 cm. For the Kruger National Park, size values for males are a maximum of 345 cm, for females 274 cm, with 255 cm rarely exceeded. Maximum weights for bulls are given as 6048 kg, for cows 3232 kg. One particularly large individual weighed 6569 kg. The largest scientifically measured specimen, an animal from Fenykoevi in Angola, had a shoulder height of 400 cm and a weight of about 10 t; it is now on display at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

The head is massive and large, broader in adult bulls than in cows and younger individuals. In contrast to the high-arched, bicuspid forehead of the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), the African elephant has a flat, receding forehead. The characteristic large ears measure about 120 cm in width and up to 200 cm in height. Their outline is somewhat reminiscent of the contours of the African continent. They are significantly larger compared to the Asian elephant. The trunk ends in two "fingers", the Asian elephant has only one. Another difference to the Asian elephant can be found in the course of the back, which is rather saddled in the African elephant, so that the highest point is reached at the shoulders. The Asian elephant has a characteristic humped back and the highest point of the body is on the forehead. The forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis), on the other hand, has a rather straight back line. The general skin coloration corresponds to a pale gray to brown tone, in rare cases light, pigment-free spots are visible. The thickness of the skin reaches up to 40 mm on the legs, the front of the head and on the back, it is generally wrinkled. The body hair is sparsely distributed over the body. However, young animals often have a loose, reddish-brown coat. Longer hairs on adults are usually only on the chin and trunk, and are about 40 mm long. In addition, there is a tuft of up to 50 cm long, partly blackish shiny hairs at the end of the tail. The front and hind feet each have five toes. Externally, four to five hoof-like nails are developed in front and three to five in the rear. The sole is soft and cracked as well as individually shaped. It leaves characteristic roundish marks. Those of the forefeet generally exceed those of the hindfeet. The length of the hind feet varies from 34 to 54 cm, it is proportional to the shoulder height of an animal.

Skull and dentition characteristics

The skull is generally built large, a measured specimen had a length of 92 cm and at the zygomatic arches a width of 73 cm. Compared to the Asian elephant, the skull of the African elephant is clearly more rounded and less high. The forehead line in the front view of the African elephants is rather straight or curved and not as distinctively indented as in the Asian elephants. Typical of elephant skulls are the extensive air-filled chambers in the top of the skull, reminiscent of honeycombs. On the one hand, they reduce the weight of the skull, but on the other hand, they also increase the surface area, which provides more attachment surfaces for the massive neck and masticatory muscles. Due to the extreme pneumatizations, the skull can be up to 30 or 40 cm thick. The facial region of the skull is formed by the nasal bones, the maxilla, the zygomatic bone and the middle jaw bone. The nasal bone appears small due to the trunk formation, and the nasal opening is at the level of the orbit and thus lower than in the Asian elephant. The middle jaw bone forms the outer shell of the alveoli of the tusks. In the African elephant, the alveoli are laterally spaced and project slightly forward, whereas in the Asian elephant they are directed directly downward. As a general characteristic of Tethytheria, the median jawbone fuses with the frontal bone, among others. The frontal bone itself is very broad and rounded in design in the African elephant, but narrow in the Asian elephant as it retracts above the nasal opening. The parietal bones represent the largest bones of the skull. On them, a small furrow runs downwards, which is more prominent in the Asian elephant. On the occipital bone, the articular surfaces for articulation with the cervical spine point clearly backwards. They are also at the level of the orbit and thus lower than in the Asian counterpart. The external auditory canal is located immediately near the occipital joints, whereas it is positioned lower in the Asian elephant.

The lower jaw has a rather graceful structure with a long and low horizontal bone body. It differs from the broad and swollen lower jaw of the Asian elephant. When viewed from above, it is V-shaped, whereas that of the Asian elephant is more U-shaped. Overall, the mandible consists of massive, compact bone. The symphysis at the front of the lower jaw, which connects the two arches of the jaw, extends forward in a long and narrow process. The bone joint itself is relatively and absolutely shorter than in the smaller forest elephant, averaging 17 cm in length. Several openings are formed on the outside, called the lateral and middle mental foramen. The posterior end of the mandible appears rounded by the curved angular process. The ascending branch is broad, and the crown process rises only slightly above the masticatory plane and lies about halfway along the entire length of the mandible. It is straight in shape in contrast to the rounded crown process of the Asian elephant. The articular process in turn runs straight up and not angled inward as in the Asian relative. On the inner side of the ascending branch a large foramen mandibulae opens. The outer side, on the other hand, harbors the shallowly indented fossa masseterica, which is not as deeply pronounced as in the Asian elephant.

The dentition is composed of 26 teeth grouped into the following dental formula:

As in all modern elephants, the posterior dentition consists of three premolars and three molars per half of the jaw. The change of teeth takes place horizontally, in that a new tooth pushes out from behind when the previous one is largely chewed off. As a result, the African elephant (like the Asian elephant) changes its teeth a total of five times after the first tooth (premolar dP2) erupts. Usually the first tooth is already functional at birth and falls out at the age of 1 to 2 years. The eruption of the other teeth occurs for the premolars at 1.5 (premolar dP3) and 2 years (premolar dP4) and for the molars at 5 (molar M1), 15 (molar M2) and 23 years (molar M3). The corresponding loss occurs at 3 to 4 (dP3), 9 to 10 (dP4), 19 to 25 (M1), 43 (M2) and around 65 (M3) years. However, there is a high individual range here. The horizontal change of teeth has the additional effect that only one to a maximum of one and a half teeth per jaw half are in use at the same time. In the overall dental structure, the African elephant represents the more conservative form compared to the Asian elephant. Thus, the teeth generally have lower dental crowns compared to their Asian cousin. As with all representatives of the elephants, both the premolars and molars consist of several lamellar enamel folds. The number varies between teeth, the second premolar consists of five enamel folds, the third molar of an average of 13 with variations between 14 and 16. The lamellar frequency is thus on average 5.5 (number of lamellae per 10 cm of tooth length). Both characteristics are significantly lower than in the Asian elephant. In contrast, the enamel of each lamella is markedly thicker at 2 to 5 mm. When viewed from above the chewing surface, the enamel curves outward in a diamond shape approximately in the middle of each enamel fold, whereas in the Asian elephant it is largely parallel. The last molar is the largest grinder in the dentition. It can grow up to 21 cm long and reach a weight of about 3.7 kg. The first premolar, on the other hand, is only 2.4 cm long and weighs just under 10 g.

Skull of the African elephant; clearly visible are the nasal opening in the middle and the alveoli of the tusks below.

Molar teeth of elephants in comparison. Top: African elephant. Middle: Asian elephant. Bottom: Woolly mammoth.

Distribution

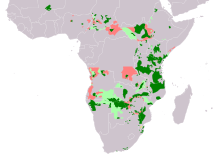

The original range of the African elephant encompassed the entire African continent and once included northern Africa as far as the Mediterranean coast and southern Africa as far as the Cape of Good Hope. Evidence of this includes various rock paintings and ancient historical accounts. However, climatic fluctuations during the Holocene displaced the species from the extremely arid landscapes. The northern populations finally disappeared already in the first centuries of the modern era. Today's occurrence is limited to sub-Saharan Africa. According to estimates, African elephants today inhabit an area of just under 5.2 million square kilometres, of which slightly more than half is accounted for by Central and West Africa, where the forest elephant also occurs. As a result, the current range of the African elephant occupies only about 20% of its former habitat. The populated landscapes are highly fragmented and patchy, with individual areas rarely visited by the African elephant. The decline in the distribution of the African elephant is mainly due to ivory poaching and habitat destruction. This affects areas in West and South Africa, among others. A small population of around three hundred desert-dwelling elephants persists in Mali near Gourma, while a larger group of over 3000 individuals is found in the WAP National Park complex. Other northern populations are found in Chad, which also represents the northern limit of the present distribution. In adjacent Central Africa and in more southern West Africa, the African elephant is replaced by the smaller forest elephant. Here, among other places, there is a more or less wide corridor where the two species hybridize. Comparatively common in East Africa, the African elephant occurs here in numerous fragmented habitats in Ethiopia, Uganda, Rwanda, Kenya and Tanzania. The largest contiguous population is found in the northern part of southern Africa, extending from Namibia and Angola in the west eastward through Botswana, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. From the southern part of southern Africa, the African elephant has largely disappeared. However, it has been reintroduced in various places by animals from the Kruger National Park.

The African elephant has adapted to a variety of habitats. These consist of semi-deserts, open grasslands and savannahs, floodplains or swamps, as well as a variety of different forest biotopes such as gallery forests, mountain forests or tropical lowland rainforests. Prerequisites for the presence of the African elephant are sufficient water and food. Shade or refuge areas for protection also play an important role in their distribution. Elephants do not usually live in deserts. Exceptions are the already mentioned populations of the southern Sahara in Mali and the border areas to the Namib, for example Kaokoveld and Damaraland, in Namibia, where there are also some populations of "desert elephants". In the mountains, the African elephant is occasionally found at altitudes up to 4875 m, such as on Mount Kilimanjaro; however, its preferred habitat is in the lowlands.

The highly fragmented range of the African elephant results in varying population sizes and densities. In open grasslands, the number of animals is about 0.5 to 2 individuals per square kilometre; it can increase to about 5 per square kilometre in areas of forested land with rich food supply, such as in Lake Manyara National Park. For ecological reasons, however, such high population densities are considered rather unstable over a long period of time. Dense forests or deserts, on the other hand, usually support only a small population of animals. Estimates of the total number of individuals in Africa are difficult, as they require a clear separation at least for those countries with a co-occurrence of the forest elephant and/or hybrids between the two species. For 2007, the figures were about 496,000 individuals in western, eastern and southern Africa, and for 1991, roughly 267,000 to 372,000 were assumed. The Great Elephant Census yielded a total of 352,000 animals in 18 countries for 2014, a 30% decline from 2007. According to this, the largest populations are found in the northern part of southern Africa, i.e. the area with the largest contiguous population, where about 234,000 animals live, followed by eastern Africa with about 73,000 animals.

Distribution of the African elephant: Year round occurrence Probable year-round occurrence Population probably extinct Resettlement areas

"Desert Elephants" in the Huab River

Search within the encyclopedia