Avian influenza

![]()

This article deals with influenza in avian species in general. For information on the current outbreaks of influenza A/H5N1 and A/H7N9, see avian influenza H5N1 and avian influenza H7N9.

Avian influenza is also known as avian influenza (from the Latin avis, bird), as bird flu and since 1981 predominantly as highly pathogenic avian influenza virus infection (HPAI). It is a notifiable viral disease that can affect chickens, turkeys, geese, ducks, wild waterfowl, and other birds in the field and in human care. When infected with the more aggressive strains of the virus, it usually results in death of the infected birds unless they are reservoir hosts. Some variants of avian influenza viruses, particularly variant A/H5N1, have been transmitted to humans, zoo animals such as leopards, and domestic cats in isolated cases. HPAIV and LPAIV of subtypes A/H5 and A/H7 in wild birds and poultry are subject to animal health legislation and therefore notifiable.

Avian influenza was first observed in Italy in 1878. In the 1930s, there were several outbreaks in Europe, America and Asia. When avian influenza spread to Ireland and the USA in 1983, millions of birds were killed there to contain the outbreaks. There was another major outbreak in Mexico in 1992, in Hong Kong in 1997, in the USA in 2015, in Germany in 2016/2017 and in 2020/2021, especially in the turkey-dense regions of Lower Saxony.

As a consequence of the events related to avian influenza H5N1, avian influenza H7N9 and avian influenza H5N8, influenza subtypes A/H5N1, A/H7N9 and A/H5N8 received particular media attention.

Whether the so-called English sweat, which was accompanied by bird deaths in the 15th and 16th centuries, was also a disease caused by influenza viruses is uncertain.

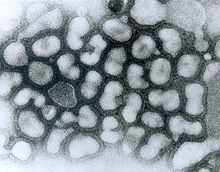

Avian influenza virus (HPAIV), electron micrograph

Pathogen

The agent of classical avian influenza (CP) is an influenza A virus (i.e. influenza virus) designated as highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAIV) and is therefore an enveloped single (-)-stranded RNA virus [ss(-)RNA] belonging to the orthomyxovirus family.

In general, the OIE Manual distinguishes between 3 types.

- LPAIV (Low pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus): low pathogenic virus, not subtype H5, H7

- LPNAIV (Low pathogenic notifiable influenza virus): low pathogenic virus (IVPI < 1.2 or corresponding haemagglutinin sequence) of type H5 or H7.

- HPNAIV (Highly pathogenic notifiable influenza virus): highly pathogenic virus (IVPI > 1.2 or typical haemagglutinin sequence with basic amino acids at the cleavage site) of type H5 or H7.

The correct name of an influenza virus would be as follows: A/goose/Guangdong/1/96 (H5N1): 'A' for the influenza subtype (A, B or C); 'goose' for the English name of the host from which the virus was first isolated; 'Guangdong' for the place name of the first occurrence, the first number representing the number of the sample and the second number denoting the year.

It was not until 1954 that Werner Schäfer, a German virologist working at the Max Planck Institute for Virus Research in Tübingen at the time, finally proved that the viruses of human influenza and classical avian influenza belonged to the same group.

Subtypes and pathogenicity

→ Main article: List of subtypes of influenza A virus

As a result of genetic changes, new variants of influenza viruses are constantly emerging. These variants are classified into subtypes on the basis of certain surface properties (for a detailed explanation of the variability of the pathogens, see Influenza). A distinction is made between 18 H subtypes and 11 N subtypes. Type A/H5N1, for example, has the 5th variant of haemagglutinin (H5) and the 1st variant of neuraminidase (N1) on its surface. These subtypes usually only infect certain hosts, while they can be spread by a further number of infection vectors without these animals becoming ill.

However, mutations can significantly alter both the host species and the pathogenic properties. Here, the surface protein haemagglutinin plays an important role, which is responsible for the recognition and attachment of the virion to the host cell. This haemagglutinin is formed as precursor HA0 and must subsequently be cleaved into two subunits (HA1 & HA2) by certain enzymes of the host, so-called proteases, so that the viruses can infect new cells.

The haemagglutinin of the low pathogenic virus strains (they are also called low pathogenic or LPAI) can only be cleaved by extracellular trypsin-like proteases, which are only present in the respiratory and digestive tract and thus limit the infection locally.

The cleavage site of highly pathogenic viral strains (HPAI) contains basic amino acids, so that it is cleaved by ubiquitous intracellular so-called furin-like proteases, thus allowing infection of the whole host.

Highly pathogenic variants are so far only known from the HA subtypes H5 and H7.

In waterfowl such as ducks and geese, many of the possible combinations of H and N have been detected, including low pathogenic variants of A/H5N1. Since no natural reservoir for highly pathogenic variants of the avian influenza viruses has been detected so far, virologists currently assume that the transition from a less pathogenic to a highly pathogenic state was the result of a mutation that at the same time allowed the species barrier from duck birds (Anatidae) to chicken birds (Galliformes) to be overcome. According to Science in October 2005, such transitions have occurred at least 19 times since 1959, each time resulting in an epidemic among breeding poultry. In some of these cases, it was even possible to trace the path from low pathogenic status in waterfowl to low pathogenic status in chicken birds to highly pathogenic status in chicken birds. However, with regard to the spread of H5N1 avian influenza, it was added in June 2006 that the commercial poultry trade was the main route of transmission.

The risk of transmission from infected intensive livestock holdings to wild birds is a problem that has received little attention to date. Due to the high density of intensive livestock housing, pathogens can be transmitted rapidly, and faeces in combination with litter, dander and feather fragments form a potentially highly infectious fine dust, which can be widely distributed with the mostly unfiltered exhaust air to the surrounding farmland, so that pathogens can be ingested by grazing geese or other wild birds. Fertilization with poultry manure represents another possible transmission route to wild birds. Overall, flocks of wild birds and farms with free-ranging poultry can therefore be judged to be more biosecure than large poultry farms, which are interconnected worldwide: Thus, isolated occurrences of certain pathogen types can only be explained by trade routes, but not by bird migration routes.

The following subtypes in particular have caused considerable damage in poultry farms:

A/H5N1

The A/H5N1 subtype is considered particularly aggressive (HPAI, Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza). An altered non-structural gene leads to the fact that certain messenger substances of the immune system, which normally ward off viruses, no longer have any effect on the A/H5N1 subtype. It therefore kills infected birds that are not part of its viral reservoir very quickly and is closely watched by scientists for interdependencies with other strains and crossings of the species barrier because of its pathogenic properties; according to the World Health Organization, A/H5N1 is the only subtype of the H5 group that is transmissible to humans. For more details on current outbreaks of A/H5N1 among poultry and humans, see Avian Influenza H5N1 and Spread of H5N1.

A highly pathogenic avian A/H5N1 virus first appeared in chicken birds in Scotland in 1959: A/chicken/Scotland/59 (H5N1).

A/H5N2

The A/H5N2 subtype occurred, inter alia, in Japan in the summer of 2005, as a result of which, according to press reports, more than 1.5 million chickens and other poultry were killed. There had already been several outbreaks in poultry farms in the USA in 1983 and 1984, as a result of which 17 million animals were killed. There were also several outbreaks in Mexico between 1992 and 1995. In December 2008, a low pathogenic H5N2 virus was detected in Belgium and Germany. This led to the culling of three poultry flocks in Lower Saxony.

A/H5N3

Subtype A/H5N3 caused a large mortality among free-living terns in South Africa in 1961. This was also the first detection of influenza viruses in a wild bird population. In October 2008, a low pathogenic H5N3 virus was detected in a goose at Leipzig Zoo during a routine check. In the same year, outbreaks occurred in several commercial poultry farms in the district of Cloppenburg, Lower Saxony. As a result, more than 560,000 poultry were killed in this region by the end of January 2009.

A/H7N1

A massive epidemic of subtype A/H7N1 occurred in Italy from March 1999 onwards, affecting more than 13 million animals by early 2000. Transmission to humans was not detectable.

A/H7N3

In North America, the spread of subtype A/H7N3 has been confirmed several times. Most recently, in April 2004, 18 farms in British Columbia were quarantined and two cases of transmission to humans were documented.

A/H7N7

In the Netherlands, 89 human infections with the (HPAI, Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza) subtype A/H7N7 were confirmed in 2003. One case was fatal. This case involved a veterinarian in whom this virus subtype was detected in lung tissue. In addition, 30,000 farmed birds had to be killed. In 1996, infection occurred in the United Kingdom. In 2013, in an attempt to reconstruct the reassortment of influenza A viruses that preceded the H7N9 avian influenza outbreak, a previously unknown variant of A/H7N7 was isolated from free-range chickens in China and was also transmissible to ferrets in the laboratory; ferrets are considered a model organism for humans with regard to influenza.

A/H7N9

Presumably after contact with infected poultry, the so-called avian influenza H7N9 also infected humans for the first time in February 2013 and caused human deaths in the People's Republic of China due to the influenza A virus H7N9.

Transmission

Avian influenza can infect all species of birds. The natural reservoir for the virus is wild ducks and other waterfowl, but they do not usually become severely ill because the virus has adapted to them. It needs these reservoir hosts to reproduce. Chickens and turkeys are particularly at risk, but so are pheasants, quail, guinea fowl and wild birds. Migratory waterfowl, seabirds and shorebirds are less susceptible to contracting the disease. However, they are vectors and their migratory behaviour contributes to the wide geographical spread. Although pigeons themselves are not thought to be very susceptible to avian influenza viruses, it is feared that they spread the pathogens as mechanical vectors in their plumage. Thus, during a rampant avian influenza outbreak in 2003, a ban on pigeon flights was declared by the North Rhine-Westphalian Ministry of the Environment.

Mammals are less susceptible to the virus, but are occasionally infected - such as domestic pigs. In Thailand, tigers and leopards in two zoos were reported to have died from A/H5N1 after eating infected poultry.

Basically, the same infection routes are observed as with other influenza viruses. The viruses spread by droplet infection via the inhaled air or via faecal particles on clothing and equipment. Outside their hosts, avian influenza pathogens are usually functional for only a few days, or many months under the most favorable conditions. Avian influenza viruses generally remain intact for 105 days in liquid manure, 30 to 35 days in feces and poultry meat or eggs at 4°C, and for seven days at 20°C. According to current knowledge, transmission via cooked poultry and other meat products is excluded.

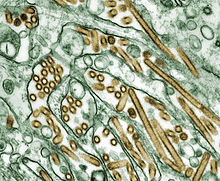

Electron micrograph of A/H5N1 (virus is stained golden)

Symptoms

The acute form of avian influenza manifests itself in signs of general weakness (apathy, inappetence, dull, shaggy plumage), high fever, difficult breathing with an open beak, oedema of the head, neck, comb, wattles, legs and feet, blue discolouration of the skin and mucous membranes, watery, mucous and greenish diarrhoea and neurological disorders (strange posture of the head, motor disorders).

In chronic cases, the laying performance decreases and the eggs are thin-walled or shell-less.

Mortality depends on the age of the animals and the virulence of the pathogen. In the case of highly virulent pathogens, the disease is fatal in almost all animals. More than 15 % of a poultry flock can die before symptoms appear (peracute course).

Questions and Answers

Q: What is avian influenza?

A: Avian influenza, also known as bird flu or grippe of the birds, is an illness caused by a virus called influenza A or type A. It usually lives in birds but can sometimes infect mammals, including humans.

Q: When was avian influenza first discovered?

A: Avian influenza was first found in a bird in Italy in 1878.

Q: What are the symptoms of avian influenza?

A: Most types of avian influenza have weak symptoms such as breathing problems similar to the common cold. However, some types can be fatal for both birds and humans.

Q: How many people did Spanish flu kill?

A: Spanish flu killed 50 to 100 million people between 1918 and 1920.

Q: How many people were killed by Asian Flu and Hong Kong Flu?

A: Asian Flu killed one million people in 1957 and Hong Kong Flu killed one million people in 1968.

Q: What is H5N1 and when did it first cause fatalities among humans?

A: H5N1 is a subtype of avian influenza which caused six fatalities among humans in Hong Kong in 1997 before causing further deaths again 2003 onwards primarily within southeast Asia but since then has spread to parts of Africa and Europe.

Q: What measures are governments taking to deal with this problem?

A Governments around the world are spending money on activities such as studying H5N1, creating vaccines, conducting pandemic practice exercises, stockpiling useful flu medication, etc., to deal with this problem.

Search within the encyclopedia