Aerial warfare

Air warfare is a form of warfare in which military operations are conducted primarily by air forces and air assets of other branches of the armed forces. The bombing of undefended cities, buildings and homes violates the international law of war.

![]()

This article or section needs revision: 1.) The statements about the structure of the air war are not supported by sources. 2.) The types of operations are subject to constant change. The lemma deals with air warfare at all times, so today's terminology is not always accurate, or was not always in use.

Please help to improve it, and then remove this marker.

Warfare can be roughly divided into:

- War in the air: Combating enemy aircraft with own fighter planes and ground-based air defense.

- Air warfare: primarily reconnaissance and engagement of ground targets, including enemy air forces on the ground, by reconnaissance aircraft and bombers. This is also known as tactical air warfare. Its three tasks or objectives are

- attacking enemy ground targets in close proximity to friendly units (close air support)

- air interdiction (engaging tactical objectives in the rear - such as bridges, roads and supplies - behind the enemy war front).

- strategic air warfare with the destruction of enemy military and political command and control facilities including their means of communication, production facilities for military armaments (aircraft and tanks), electricity plants and overland power lines, fuel refineries and other (gas) energy facilities, air, land and water transport routes and facilities (airports, seaports and docks) as well as production capacities food industry.

According to Daniel Moran, the integration of air warfare into general warfare was considered the "central military challenge of the 20th century." While the original hope that air warfare could act as a deterrent or be militarily omnipotent had not been fulfilled, air warfare had established itself as a crucial element of the battle of the linked weapons.

Important theorists of air warfare were or are Giulio Douhet (1869-1930), Billy Mitchell (1879-1936), John Boyd (1927-1997) and John Warden (* 1943).

Area bombardments, example Heilbronn, 31 March 1945

Air battles between American and Japanese air forces, June 1942 (Diorama)

The beginning

The first wartime use of airspace consisted of the use of balloons for reconnaissance purposes ("field airships") and for directing artillery fire.

Hot air balloons were first used by revolutionary France to observe enemy positions in 1793, the year in which the Aéronautique Militaire was founded. A tethered balloon filled with hydrogen, the "Intrépide", was captured by the Imperial Army at the Battle of Würzburg on 3 September 1796. It is housed in the Museum of Military History in Vienna and is considered the oldest surviving military flying machine today.

The first aerial attack on a city took place in the revolutionary years of 1848 and 1849: During the siege of Venice, the Austrian field marshal lieutenant, artillery expert, weapons engineer and inventor Franz von Uchatius proposed to have bombs dropped on the city by unmanned balloons. Three weeks later, this first air raid in world history actually took place, using 110 balloon bombs manufactured by Uchatius. Also to break the siege of the city of Sevastopol in 1855 during the Crimean War, British Admiral Thomas Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald had an idea for dropping barrel bombs filled with chemicals by means of a balloon over the city, which was explained by the French aeronaut Gardonia in a lecture in London.

Balloons were occasionally used for reconnaissance during the American Civil War.

The first use of an aircraft for warfare took place during the Italian-Turkish War on 23 October 1911 in the form of a reconnaissance flight by Carlo Maria Piazza in a Blériot XI in Tripolitania. The first bombing raid followed on 1 November 1911, when Giulio Gavotti dropped three 2-kg bombs by hand from an Etrich Taube on a Turkish military camp. On 4 March 1912, the first night flight was made by Piazza and Gavotti under a full moon, and on 17 August 1912 the first pilot was injured in the air by rifle fire from the ground. Lieutenant Piero Manzini, who crashed and died during a reconnaissance flight over enemy territory on August 25, 1912, was also the first aviator to die during a wartime event in this war.

The Italian General Giulio Douhet subsequently founded his theory of bombing war, according to which aircraft should be built specifically for bombing. Thus, he is considered the founder of air war theory. However, his plans to prepare Italy completely for air warfare met with great resistance. When he commissioned the construction of bombers without authorization, he was transferred to the infantry under disciplinary law. Later he was even arrested; only when Italy entered World War I in 1915 (see Treaty of London (1915)) and suffered devastating defeats was he recalled to his position.

During the Mexican Revolution, the Northern forces used nine aircraft flown by American pilots. Thus, after the Italian-Turkish War, this conflict was the second armed conflict in which aircraft were used.

All major powers built up air units, but these were still part of the army or navy. See e.g. Royal Flying Corps (RFC), French Air Force, USAF, Air Force of the Russian Empire.

War balloon "Intrepide"

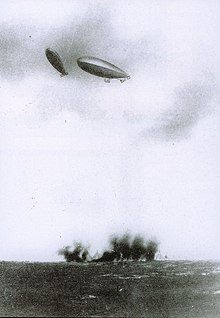

Italian airships bomb Ottoman positions in the Italian-Turkish War

World War I

World War I saw the development of most of the air war concepts that defined the air war until the Vietnam War and, to some extent, beyond.

Probably the first air raid of the First World War took place on Liège: At three o'clock in the morning on 6 August 1914, the German Zeppelin LZ 21/"Z VI" flew over Liège and dropped bombs that killed nine civilians.

Air reconnaissance

At the beginning of the war (1914), the Central Powers and the Entente concentrated mainly on operational long-range reconnaissance. In the course of the war, aerial cameras ("Reihenbildgeräte") were developed, the photos of which were used for military reconnaissance.

The first decisive success of air reconnaissance was the reports of the British Royal Flying Corps (RFC), which made it possible to intercept the German advance towards the Marne. This meant that the Schlieffen Plan could no longer be fulfilled and the war on the Western Front developed into a war of position.

When trench warfare began, tethered balloons and two-seater radio-equipped aircraft were used to direct artillery fire. The introduction of telegraphic extinguishing radio transmitters from 1915 onwards was tantamount to the actual beginning of aeronautical radio. Attempts were made, especially by the British, to use balloons and aircraft to drop spies behind enemy lines.

Air superiority

The realization developed that balloons and reconnaissance planes had to be attacked directly from the air, since there was a lack of sufficient and practical anti-aircraft capabilities from the ground. The development of true fighter aircraft, with which a pilot could fire in the direction of the aircraft's longitudinal axis without the aid of a gunner flying with him, originated with the French pilot Roland Garros. He attached a forward-facing machine gun to a Morane-Saulnier L and reinforced the rear of the propeller so that he could fire through the propeller circle without damaging the propeller. A Fokker-developed breaker gear for airscrew-synchronous release of the machine guns was a useful development of this method. The Fokker E-I equipped with it is considered to be the first series-produced fighter aircraft in the world.

On the Allied side, a pressurized propeller arrangement was used initially, later with rigidly mounted weapons aligned across the propeller circle. The structures for commanding units in combat were borrowed from the cavalry and continuously developed. The British pilot Lanoe Hawker was an early advocate of disciplined formation flying at the RFC. On the Allied side, the division into squadrons was retained, while on the German side, squadrons were formed, which corresponded to squadrons in terms of numbers, and squadrons, which combined several squadrons.

In the course of the war, the Allies set up their units as separate forces that were allowed to operate independently of the army command. A little later, regular patrol flights were added, through which the French and British could control the entire Western Front.

The Germans responded by conducting "blocking flights". This tactic required German crews to be stationed close to the front lines in order to close the airspace through constant surveillance. However, such an approach required a large number of fighter aircraft, which had to operate in a concentrated manner in a narrow area and were therefore unavailable for other actions.

In October 1916, at the suggestion of the experienced fighter pilot Oswald Boelcke, a restructuring of the German Air Force took place, which was now established as an independent force alongside the Army and Navy. Furthermore, Boelcke selected some outstanding aviators in his own ranks, whom he personally trained in air combat and deployed in the legendary "Jagdstaffel 2". In order to pass on his experiences, he summarized the most important basics of air combat in the Dicta Boelcke.

When the Americans intervened in the fighting in 1918, the Allied air forces were able to push back the Germans through their numerical superiority. Despite armament efforts, they had to limit themselves to gaining air superiority at least in a limited area.

Strategic Bombing

Bombs and propaganda material were dropped by planes over enemy cities early in the war.

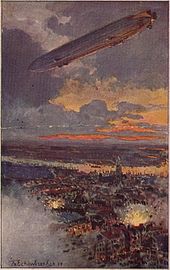

The first cities to be bombed by a German Zeppelin were Liège and Antwerp on August 6 and 24, 1914. The first German bomb dropped on British soil was by Fliegerleutnant Hans von Prondzynski at Dover on December 24. The bomb he dropped missed its intended target, Dover Castle, and landed in the parish garden of St. James. A British aircraft which subsequently ascended was unable to locate the attacker. On 19 January 1915, the East of England towns of Great Yarmouth and King's Lynn in Norfolk were bombed by Zeppelins L3 and L4. On 31 May the first bombing raid on London was flown.

Almost simultaneously, the first bomb sights were developed with the "Dorana" and the "Lafay". The hit probability could be improved considerably by them, although they were very simple.

In 1916 the bombing raids were intensified. Now, in addition to the explosive bombs, incendiary bombs were also used, causing great damage, especially in England. The most devastating attacks were carried out by German planes between 31 March and 6 April, forcing the British to black out or completely shut down their workplaces in case of danger.

At first, the Germans particularly used airships for bombing. From 1917 onwards, large aircraft, later also giant aircraft, were built in Germany as strategic bombers, which were used in bomb squadrons of the Supreme Army Command or giant aircraft divisions. They replaced airships as the main means of bombing. The large aircraft reached higher speeds and were thus more difficult to intercept.

Overall, the bombing had military and strategic benefits that went far beyond material damage. Great Britain had to invest considerable resources in building up an air defence system and deploy large numbers of airmen to home defence rather than to front-line combat. The loss of production due to bombing alerts was greater than the direct damage done. In total, about 1400 people lost their lives as a result of German air raids on England.

A total of 15,471 bombs were dropped over the German Reich, killing 746 and wounding 1843. The state of Baden was hardest hit, with 678 killed and wounded.

See also: Zeppelins in the First World War and Schütte-Lanz

ground combat support

→ Main article: Tactical air warfare

During the First World War, fighter planes were already used to fight infantrymen and tanks. To attack enemy soldiers, the crews not only made use of the on-board MG, but also sometimes threw long thick nails, so-called fléchettes, from the aircraft. In operations against tanks, bombs were used, which were first thrown manually at their target. Later in the war, the bombs were suspended from the underside of the aircraft and released over the target.

In the war year 1917, so-called battle squadrons were set up on the German side, whose aircraft were specifically intended for use against ground targets. The aircraft of the battle squadrons were armored on their underside and intervened low-flying in ground battles. However, due to the technical possibilities of armament and aiming devices at that time, the usefulness of the battle squadrons was limited. On the Allied side regular fighter planes were used for such purposes, which additionally intervened in land battles. On the whole, however, the latter strategy proved too disadvantageous - the fighter pilots were not trained for attacks on ground targets, the armament of the fighter planes was not very effective against ground targets, and conversely, the largely unarmored fighter models were extremely sensitive to concentrated defensive fire from even simple infantry weapons, which led to high losses in such operations. Consequently, in the further development of fighter aircraft after the war, the Allies also adopted the principle of developing and deploying specialized fighter aircraft or fighter-bombers for attacks against ground targets.

Air Defense

→ Main article: Air defence

Since before the war only Germany was researching anti-aircraft guns, the front-line soldiers had to improvise until appropriate weapons were available on all sides.

On simple machine guns lacked the ability to aim properly. Especially enemy balloons were difficult to shoot down, which is why the fight in the air was initially more important. On August 22, 1914, the first British plane was hit by rifle fire, whereupon it crashed over Belgian territory. Manfred von Richthofen fell victim to machine gun fire from the ground.

In the German cities, special posts were supposed to report to central air raid wardens, who then decided on measures such as air raid alarms or barrage fires. In addition, passive air protection was intensified, ranging from informing the population to signals by church bells, firecrackers or steam and motor sirens.

Naval Aviator

→ Main article: Naval aviators

Early on during World War I, the British converted several warships into seaplane carriers. However, these were only suitable for seaplanes, which took off from the deck and landed near the tender after completing their mission. Special cranes then lifted them aboard. HMS Ark Royal (II) is widely regarded as the first aircraft carrier, but was only equipped with seaplanes and took part in the Battle of the Dardanelles.

From the HMS Furious, a converted British cruiser, an attack on the Zeppelin hangars in Tondern was launched on 19 July 1918.

In 1910, the training of naval aviators also began in Austria-Hungary. In 1911, the first naval air station was established in the war port of Pula. By the end of 1915, the Imperial and Royal Naval Air Force had 65 combat-ready seaplanes. Seaplane Forces had 65 combat-ready seaplanes. Due to the steadily increasing number of Italian bombing raids, the use of fighter planes was soon planned. After building their own prototype, the decision was made to purchase German Fokker fighters. Liner Lieutenant Gottfried von Banfield (the "Eagle of Trieste") achieved the first aerial victory at night in air war history on 31 May 1917. At 10:30 p.m. he forced an Italian seaplane to land near Miramare Castle with his Lohner flying boat.

Although the first take-off from a ship in the USA was achieved as early as 1910 and the first landing on the USS Pennsylvania in 1911, it was not until 1918 that the first aircraft carrier suitable for take-off and landing was completed, the HMS Argus, a converted passenger ship. This came too late for wartime use in the First World War.

Romantic heroic image

During World War I, French newspapers coined the term as d'aviation (flying ace) for pilots with at least five kills of enemy aircraft. The first ace pilot was Adolphe Pégoud, the three leading "aces" of the First World War were Manfred von Richthofen (Germany), René Fonck (France) and Billy Bishop (Great Britain). Newspapers (and later films) created a romantic image of flying aces as "modern knights of the air".

Participating air forces

- Aviation Militaire (Belgian Air Force)

- Royal Flying Corps/RFC (British Flying Corps, until 1917)

- Royal Naval Air Service/RNAS (British Naval Air Service, until 1918)

- Royal Air Force/RAF (British Air Force, from 1918)

- German Air Force

- Aéronautique Militaire (French Air Force)

- Corpo Aeronautico Militare (Italian Air Force)

- k.u.k. Aviation Troops (Austro-Hungarian Aviation Troops)

- Osmanlı Hava Kuvvetler (Ottoman Air Force)

- Императорский военно-воздушный флотъ (Russian Air Force).

- Air Service of the US Army (US Air Force)

The aircraft production of the belligerent powers of the First World War

| Aircraft production in the First World War (in units) | ||||||

| Country | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | Total production |

| German Reich | 1.348 | 4.532 | 8.182 | 19.746 | 14.123 | 47.931 |

| Austria-Hungary | 70 | 238 | 931 | 1.714 | 2.438 | 5.391 |

| United Kingdom | 245 | 1.933 | 6.099 | 14.748 | 32.036 | 55.061 |

| France | 541 | 4.489 | 7.549 | 14.915 | 24.652 | 52.146 |

| United States | - – | - – | 83 | 1.807 | 11.950 | 13.840 |

| Kingdom of Italy | - – | 382 | 1.255 | 3.871 | 6.532 | 12.031 |

| Russian Empire | 535 | 1.305 | 1.870 | 1.897 | - – | 5.607 |

Play media file Australian soldiers inspect Manfred von Richthofen's downed plane (video)

Attack of a German propeller plane on an "enemy captive balloon" (1918)

Lieutenant-Colonel W. A. 'Billy' Bishop, 60th Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps, in front of his Nieuport 17 Scout

Miramare Castle

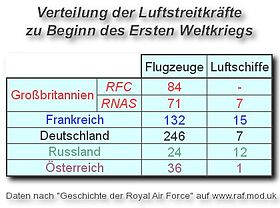

allocation of air power

Eugene B. Ely shortly before landing on the USS Pennsylvania

Play media file American air raid

Shooting down of the Zeppelin LZ 37 by a British airplane, artistic representation, 1915

Bombardment of Antwerp by a Zeppelin in 1914, painting by Themistokles von Eckenbrecher

Search within the encyclopedia