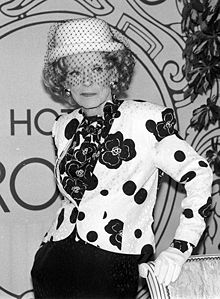

Bette Davis

![]()

This article describes the actress Bette Davis. For the singer see Betty Davis.

Ruth Elizabeth "Bette" Davis (born April 5, 1908 in Lowell, Massachusetts, United States; † October 6, 1989 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France) was an American stage and film actress.

Bette Davis began her career in the theater before moving to Hollywood in 1930 and starring in over one hundred films until 1989. She was best known for her portrayal of complex characters. At the height of her career, Davis starred mostly in film dramas whose plots revolved mostly around the tragic fate of the female lead. However, she also appeared in historical films and, late in her career, in film productions whose strong grand guignol elements sometimes brushed the line with horror films. Davis' trademarks were her large, expressive eyes, her direct manner and her ubiquitous cigarettes.

Bette Davis won the Oscar twice for Best Actress in a Leading Role and was nominated eight more times for the award in this category. She always fought vehemently against the restrictions of the studio system and for good roles and more say in the selection of film roles. In 1936 she sued her film studio Warner Brothers, albeit in vain, in a sensational lawsuit. Bette Davis was the first woman to preside over the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as president. During World War II she founded the Hollywood Canteen with other actors.

Bette Davis became the first film actress to be honored with the American Film Institute's (AFI) Lifetime Achievement Award in 1977. In a 1999 AFI poll, she was ranked second among America's greatest female film stars. She was a public figure until her death, despite various illnesses, and frequently appeared on American talk shows due to her popularity with the public.

In 1983, Davis' daughter B. D. Hyman wrote about her negative childhood memories in the highly controversial tell-all book My Mother's Keeper.

Bette Davis 1987

Life and work

Childhood and early career

Ruth Elizabeth Davis was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, the daughter of Ruth ("Ruthie") Favor and attorney Harlow Morrell Davis. Her sister Barbara ("Bobby") was born on October 25, 1909. The family was of Protestant denomination and had English, French, and Welsh roots. In 1915 Davis' parents separated. That same year, the two children began school at Crestalban School in Lanesborough, Massachusetts.

In 1921, Ruth Favor moved with her daughters to New York City, where she worked as a professional portrait photographer to support the family. It was at this time that Davis first expressed a desire to become an actress. She was inspired primarily by Rudolph Valentino in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) and Mary Pickford in Little Lord Fauntleroy (1921), also changing her name to "Bette" in reference to Honoré de Balzac's La Cousine Bette. In 1924, Ruth Favor Davis sent her daughters to Northfield Seminary for Young Ladies, a denominational boarding school for girls. A semester later, the girls transferred to Cushing Academy, a boarding school in Ashburnham, Massachusetts.

In 1926, Davis saw a theatrical production of Henrik Ibsen's The Wild Duck, starring Peg Entwistle, at the Repertory Theatre in Boston. Years afterward, she said of the performance, "Before the performance I wanted to be an actress. Afterward, I had to be an actress...just like Peg Entwistle." Davis attended an audition for inclusion in Eva Le Gallienne's Manhattan Civic Repertory. However, Le Gallienne found that Davis's attitude toward the theater was not serious enough, and declined the admission. Later, partly through the efforts of her mother, Davis was accepted to the John Murray Anderson School of Theatre. Thus, Davis was initially allowed to attend the school without pay, under the promise that she would repay the money at a later date. Davis received dance lessons at the school from Martha Graham, among others.

Later, Davis left Murray Anderson School early, although she had received a scholarship to study to work at the Provincetown Playhouse for director James Light. However, the production kept getting postponed and she had to temporarily look for a new engagement. She auditioned for George Cukor's Repertory Theatre Company. Although he was not enthusiastic, he gave Davis her first paid theater role as a revue dancer in the play Broadway. Shortly thereafter, the female lead, Rose Lerner, was injured during a performance and Davis was allowed to take over the part.

Cukor and Davis had a strained relationship during their collaboration. Davis rarely left his criticism and advice about her work without comment. Eventually, he fired her. After the following summer, work began at the Provincetown Playhouse Theatre in New York City for the play The Earth Between by Eugene O'Neill. Toward the end of the season, Bette Davis was chosen to play Hedwig in Ibsen's The Wild Duck. The Washington Post praised her for her "excellent" performance and devoted a short portrait to her as a theatrical "new discovery." Following her engagement there, Davis made her Broadway debut in 1929 as the rebellious daughter of Donald Meek in the comedy Broken Dishes, followed by the satire Solid South. During one performance, a Universal Studios talent scout was present and invited her to Hollywood for screen tests for the planned film adaptation of the stage play Strictly Dishonorable.

From stage to film 1931

Davis did not get the role in Strictly Dishonorable (1931), and she also failed to be recommended for the film A House Divided (1931). Davis was, however, used to test other applicants. In a 1971 interview with Dick Cavett, she recalled, "I was the [...] most shameful virgin that ever lived on earth. They put me on a couch and I tested fifteen men [...] They all had to lie on top of me and give me a passionate kiss. Oh, I thought I was going to die."

Davis finally made her film debut in the remake The Bad Sister (1931), which was not a great success. Carl Laemmle, the head of Universal Studios at the time, then refused to renew her contract, but cinematographer Karl Freund told him that Davis had "lovely eyes" and she was given a contract extension after all. Davis' next role in My Children - My Happiness (1931) was too small to attract attention, however, and small supporting roles in Waterloo Bridge (1931) and Way Back Home (1932) did not help her break into the film business. Afterwards she worked for Columbia Pictures on a loan-out for the movie The Menace (1932) and for Capital Films for Hell's House (1932).

After nine months and six rather unsuccessful films, Laemmle decided not to renew her contract. Davis' Hollywood career seemed over, but influential actor George Arliss chose her for the female lead in The Man Who Played God (1932). The film earned Davis her first serious recognition in Hollywood. The Saturday Evening Post wrote of her performance that she was not only beautiful but positively bubbly with grace, comparing her to Constance Bennett and Olive Borden. The Warner Brothers studios subsequently gave her a 26-week contract with an option to extend it to five years. In 1932, Davis married Harmon Nelson, a bandleader, in her first marriage.

Through another loan-out, Davis was given the opportunity to play the role of the anti-heroine Mildred Rogers in the RKO radio production Of Human Bondage in 1934. Mildred, a lower-class waitress, takes financial and sexual advantage of her crippled lover, played by Leslie Howard, and leaves him several times for other men. The studio had difficulty finding a suitable actress for the role after, among others, the intended Ann Harding refused to participate. Davis got the part and managed to convince the director to let her play the character as realistically as possible. In the end Bette Davis received partly hymn-like reviews. Life magazine, for example, judged her performance, "Probably the best portrayal ever given on the screen by a U.S. actress." Davis expected that the positive reviews would encourage Warner Brothers to offer her better roles. Hopes dashed, however, and Jack Warner, among others, refused to loan her out for the film It Happened One Night (1934). For Bette Davis, roles continued to be limited to inexpensively produced standard films like Housewife or supporting roles alongside established male stars like Paul Muni in City on the Border.

When Davis was not nominated for an Oscar for her performance in Of Human Bondage, it sparked widespread protests. Due to the uproar leading up to the awards, for the only time in Academy Awards history, a nominee who was not originally officially nominated was able to be chosen. In the end, Claudette Colbert won the award for It Happened in One Night. After the awards ceremony, a change was made to the voting process. Since then, nominations are no longer determined by a small committee, but are selected by all eligible industry representatives.

In 1935, Davis played a failed actress in the film Dangerous and again received very good reviews. The New York Times even called her "one of our most interesting film actresses." For her performance, Davis won the Academy Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role, but she commented on this as a belated recognition for her performance in Of Human Bondage. Since that time, she always stated that she nicknamed the Academy Award "Oscar". In her opinion, the statue looked exactly like her husband, whose middle name was Oscar. This claim was repeatedly rejected by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Among the few challenging films of the period was the role of an idealistic waitress in The Petrified Forest, the film adaptation of Robert E. Sherwood's play of the same name. Davis gave a highly acclaimed performance alongside Leslie Howard. The biggest impression, however, was left by Humphrey Bogart as a gangster with no morals. Bette Davis became increasingly frustrated with the low quality of the roles on offer. After her following movies The Golden Arrow and The Satan and the Lady were neither a financial nor an artistic success the actress decided to take a far-reaching step to give her career a new direction.

Legal dispute with Warner Brothers

Davis was convinced that her career would be destroyed by a succession of mediocre films. So in 1936 she accepted an offer to star in two films by British filmmaker Ludovico Toeplitz, even though she knew she was violating her studio contract with Warner Brothers. Jack Warner stopped her involvement by injunction. Subsequently, the studio attempted to settle the matter out of court, but the effort failed due to Davis' refusal. The trial began on October 14, 1936 in London.

Davis' main charges were that she was not given a say in the selection and realization of her roles and that she had to shoot too many films in a short time. She also criticized the bad working conditions at Warner Brothers, working hours were not kept and the cheaply produced movies had to be shot in parallel and in a very short time. Furthermore, Davis objected to the fact that when she was suspended, her contract was automatically renewed for the period of her leave. In addition, she was not permitted to make public appearances without studio approval and did not possess the right to cancel studio-mandated appointments. At the start of the trial, the lawyer representing Warner Brothers read into his opening statement that the court should conclude that Davis was a disobedient young woman who merely wanted more money. Davis, who drew a weekly salary of $1,350, according to a statement from Warner Brothers' lawyer, received little support from the British press. It portrayed her as an overpaid and ungrateful actress. The judge in charge of the case at the High Court of Justice ultimately found in favor of Warner. Davis subsequently returned to Hollywood, heavily in debt from the legal costs, to resume her career.

Success with Warner Brothers from 1937

Davis resumed her work with the film Murder in the Nightclub, which was distributed in 1937. In the gangster drama, which was inspired by the story of Lucky Luciano, she portrayed a prostitute who actively works to break up a crime ring. The film got into considerable trouble with the censorship board due to its frank depiction of prostitution and organized crime. Bette Davis was again highly praised by critics for her portrayal. With the studio's previous top female star, Kay Francis, no longer getting good roles after a bitter legal battle, many projects originally intended for Francis now went to Bette Davis, such as Three Sisters from Montana and Victims of a Great Love.

During the making of the film drama Jezebel - The Wicked Lady (1938), Davis began an affair with director William Wyler. She later described him several times as the love of her life. The film was very successful and the portrayal of the spoiled Southern belle earned Davis her second Academy Award. This left room for the press to speculate that she might be up for the role of Scarlett O'Hara in the film version of Gone with the Wind. However, producer David O. Selznick wanted to sign a lesser-known actress and gave preference to Vivien Leigh.

Jezebel marked the beginning of Davis' most successful career phase. In the years that followed, she appeared several times on Quigley's list of the ten most commercially successful stars in the United States. Her husband's limited success, however, led to a marital crisis. When he received the certainty that his wife had cheated on him several times in 1938, he divorced her. Davis was accordingly emotionally distraught during her next film, Victims of a Great Love, which was distributed in early 1939 and told the fate of a woman with only a year to live and a few happy days left, and considered dropping out. Producer Hal B. Wallis was finally able to convince her to turn her emotional despair on her game in front of the camera. The film was one of the most successful productions of the year and Davis received another Academy Award nomination. However, the award was won by Vivien Leigh for the role of Scarlett O'Hara. In later years, Davis confessed that she played her favorite role in Victims of a Great Love.

In the course of 1939 Bette Davis appeared in three more commercially successful movies. In The Old Maid she played a young woman at Miriam Hopkins' side who has to have her child raised by her cousin. The historical film Juarez presented her as the tragic Charlotte of Belgium. Her first color film, Minion of a Queen, featured her as Elizabeth I alongside Errol Flynn. Hell, Where's Your Victory (1940) became her most financially successful film to date, while The Secret of Malampur (1940) was called "one of the best films of the year" by trade magazine The Hollywood Reporter. In her private life, Davis met Arthur "Farney" Farnsworth, an innkeeper from New England. The two were married on December 31, 1940.

In January 1941, Davis became the first female president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. However, she annoyed the committee members by her brash appearance and by her radical proposals for change. Already after a few months she resigned from her office. Her successor, Jean Hersholt, proved more assertive and implemented many of the ideas she had suggested during her tenure. By this time, Davis was Warner Brothers' most successful female star and had first dibs on all the leading roles. In 1941, Davis accepted producer Samuel Goldwyn's offer to star in the William Wyler film adaptation of Lillian Hellman's play The Little Foxes as part of a loan-out. Davis received another Academy Award nomination for her portrayal of an unscrupulous wife, but lost out to Joan Fontaine in Suspicion.

Second World War

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Davis spent the first months of 1942 selling war bonds. Within two days, she sold two million dollars worth of bonds, as well as a painting of herself from Jezebel for $250,000. Davis tried to be involved in a variety of ways during wartime. Among other things, she appeared as the only white member of an acting troupe alongside Hattie McDaniel, Lena Horne, and Ethel Waters to entertain African-American soldiers in the U.S. Army. At John Garfield's suggestion that he open a soldiers' club in Hollywood, Davis, with the help of colleagues, converted an old nightclub into the Hollywood Canteen. Hollywood's biggest stars performed there to entertain the American soldiers. She later said of her involvement, "There are only a few accomplishments in my life that I am sincerely proud of. The Hollywood Canteen is one of them."

Bette Davis had one of her greatest financial and artistic successes with Journey from the Past from 1942. Warner Brothers had originally intended the actress Irene Dunne, who was working without a fixed studio contract, for the role of the oppressed daughter from the best family, who begins a new life through the love of a married man. But Davis ultimately convinced Jack Warner to give her the part. For the fifth year in a row, Davis was nominated for an Oscar for her performance, but lost to Greer Garson in Mrs. Miniver.

At her own request, Bette Davis played Paul Lukas' wife in 1943's Die Wacht am Rhein, the film adaptation of a propaganda play by Lillian Hellman in which she very clearly points out the difficult conditions in contemporary Germany. Screenwriter Dashiell Hammett expanded the wife's part, which was merely a supporting role in the play, but the actress was still unhappy with the result in the end and filming was less than satisfactory. Besides Davis also appeared in two contemporary revue movies whose proceeds were used for charitable purposes. In 1943's Thank Your Lucky Stars, Davis sings and dances during her solo number They're Either Too Young or Too Old. In it, the actress sings about the lack of men in society as draft-eligible men were drafted in the wake of World War II. In Hollywood Canteen, Bette Davis also appeared as herself and explained the mission of the institution she co-founded in the course of the plot as part of the care of the troops.

After Norma Shearer and Margaret Sullavan, among others, declined to play only the second female lead alongside Bette Davis, In Friendship Bound saw Davis and Miriam Hopkins reunite. The melodrama chronicles the tense friendship of two women that is subjected to a severe test after one of them becomes a successful book author and conflicts also arise over the love of a man. The actual rivalry between Davis and Hopkins was so strong that the originally hired director Edmund Goulding left at his own request after filming began, leaving Vincent Sherman to finish the production.

On August 23, 1943, Davis' second husband, Arthur Farnsworth, collapsed in the street and died two days later in the hospital. Davis was then offered to postpone the start of filming for her next movie, The Life of Mrs. Skeffington (1943), but she only asked for a week's delay. During filming, her moods were unpredictable and she was in constant dispute with director Vincent Sherman and lyricist Julius J. Epstein. As a result, she received very mixed reviews for her eccentrically over-the-top appearance in the film, though she also received another Academy Award nomination.

Slowly declining success from 1945

From the middle of the decade, Bette Davis faced increasing competition for good roles from other actresses after the studio agreed to contracts with Barbara Stanwyck and Rosalind Russell for a certain number of films in addition to Joan Crawford. Crawford eventually won the Academy Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role for her performance in 1945's As Long As a Heart Beats, while Davis came up empty in the nominations for The Green Grain. The role of an idealistic elderly schoolteacher who sacrificially fights against the educational emergency in a Welsh mining town was played with success on stage by Ethel Barrymore. Bette Davis faced accusations of being miscast and acting below her potential from renowned film critic James Agee, among others. The Green Grain was the only film Davis made in 1945. In the same year Davis married the artist William Grant Sherry.

The Big Lie (1946) was Davis' next film and the first she made with her own production company, B. D. Productions. Davis had Catherine Turney write the script for it, she chose her co-stars herself. The film was not very well received by the critics, but The Big Lie still did well in the cinemas. Her following film, Deceptive Passion (1946), was her first film since 1939's Minion of a Queen to show a loss.

The pregnant Davis retreated into private life until the birth of her daughter Barbara Davis Sherry (later known as B. D. Hyman). Upon her return, she was offered the female lead in African Queen (1951). When she learned that the film was to be shot in Africa, she turned it down. The role was later taken by Katharine Hepburn. Davis also refused to star alongside Joan Crawford in Women Without Men. The project was made in 1950 with Eleanor Parker under the title Women's Prison. Plans to star alongside Joan Crawford and Gary Cooper in the film version of Edith Wharton's Ethan Frome also fell through due to Davis' refusal. She unsuccessfully proposed a film biopic of Mary Todd Lincoln to studio head Jack Warner in return. In 1947, Davis was the highest-paid woman in the country, with an income of $328,000.

Her first film after the birth of her daughter was Winter Meeting, which was distributed in 1948. Davis subsequently regretted her involvement in the film. She doubted the acting talent of her colleague Jim Davis, and she disliked the fact that some scenes planned with her were not realized. One critic judged, "of all the terrible dilemmas Ms. Davis has faced [...] this is probably the worst." The film ended up losing Warner Brothers over a million US dollars. The comedy Bride of the Month, which she presented alongside Robert Montgomery, was also not a success at the box office. Reviews were mixed, and Davis was said to lack the acting chops to credibly play comedies.

Besides the financial failure of her last two movies Bette Davis also had to realize that Jane Wyman and Doris Day rose to the most popular female stars of the studio. The reasons for the rapid decline of her career were manifold and also affected other actresses of her generation like Barbara Stanwyck and Katharine Hepburn. If Bette Davis was considered the "doyenne of romantic melodrama" alongside Greer Garson at the beginning of the decade, Olivia de Havilland and Ingrid Bergman took over this position in the following years. Joan Fontaine and Susan Hayward now also played successfully in films about dramatic women's fates, which had previously been reserved for Bette Davis.

The studio nevertheless continued to have faith in Bette Davis's box office pulling power, and in 1949 the two sides agreed on a lucrative contract for four more films. The first was The Sting of Evil (1949). However, the actress was very unhappy with the script and director King Vidor, and only continued acting after Warner assured her that he would release her from her contract after the production was completed. Her career seemed over, and so the Los Angeles Examiner wrote of her last Warner film: "An undignified finale to a brilliant career."

Start of an independent career

In 1949, Davis and her then-husband Sherry fell out. She received few film offers at the time until Darryl F. Zanuck desperately needed a replacement for the role of Margo Channing in All About Eve (1950) because Claudette Colbert had been injured. The tragicomedy was the most successful film at the 1951 Academy Awards, with 14 nominations and six awards, and gave Davis an unexpected comeback. She won the Best Actress award at the Cannes Film Festival and the New York Film Critics Circle Award for her performance. Director Joseph L. Mankiewicz later said of working with Davis, "She was far more than great. She was fantastic." The film All About Eve is also the source of her most famous movie quote: "Fasten your seatbelts, it's going to be a bumpy night." (Fasten your seatbelts, ladies and gentlemen. I think it's going to be a bumpy night).

On July 3, 1950, her divorce from William Sherry was final. Twenty-five days later, Davis married fellow All About Eve actor Gary Merrill. With Sherry's permission, Merrill was subsequently able to adopt Davis' daughter, B. D. The two also adopted a girl named Margot. This was followed in 1952 by the adoption of a boy named Michael.

In Great Britain Merrill and Davis were again in front of the camera together for the film Gift für den Anderen (1951). The critics rated the film negatively and the American press already predicted Davis her next career end - despite her renewed Academy Award nomination for The Star (1952). So she got herself hired for the Broadway revue Two's Company by Jules Dassin. Lacking training and experience, however, she was not convincing on stage. In addition Davis became seriously ill. Therefore she only shot few movies in the 1950's which were not very successful. The London critic Richard Winninger judged of her: "Mrs. Davis, who has more say than most other stars, seems to have fallen prey to egotism [...] Only bad films are good enough for her." Their daughter Margot, meanwhile, was diagnosed with brain damage, likely contracted during or shortly after her birth. Davis and Merrill placed Margot in a special care facility. Family life at that time was marked by quarrels, violence and alcohol. In 1960, they divorced.

In 1961, Davis accepted an offer to play the homeless Apple Annie in Frank Capra's film The Bottom Ten Thousand (a remake of 1933's Lady for a Day). She subsequently played a Broadway role alongside Margaret Leighton and Patrick O'Neal in The Night of the Iguana for only a short time, as again there were disputes with other actors. She was not allowed to take part in the later film version of the material.

Renewed success from 1962

Davis achieved another major commercial and also artistic success with her appearance in What Really Happened to Baby Jane? (1962). It was the only film she made with her rival Joan Crawford. In order for the project to be made at all, both leading actresses initially gave up a portion of their fees, but in return negotiated a percentage of the profits. Davis received her tenth and final Academy Award nomination for Best Actress in a Leading Role and her only British Film Academy Award nomination for her portrayal of former child star Baby Jane Hudson, who torments her wheelchair-bound sister Blanche.

Davis portrayed twin sisters in the crime film The Black Circle (1964). For the time, the film was elaborate and required special camera technology. Her next engagement was in the drama Where Love Leads (1964). Once again, spats with her film partner, this time Susan Hayward, made filming difficult. Davis' last major success in the 1960s marked Robert Aldrich's Baby Jane sequel Lullaby for a Corpse (1964). Aldrich began production again with Joan Crawford as Davis' antagonist. Crawford fell ill, however, and was replaced by Olivia de Havilland at Davis' suggestion. The film was a considerable success, receiving numerous Oscar nominations.

In 1964, Bette Davis also appeared in a pilot for Aaron Spelling's new sitcom The Decorator. However, the film never aired and the project was terminated. She went on to appear in a number of British productions throughout the 1960s: Was It Really Murder? (1965), The Poisonous Injection (1968) and The Passage Room (1970). Success was limited and her career stalled again.

Late career since the 1970s

In 1972, Davis took leading roles in two pilots for potential television series, first in In the Clutches of Madame Sin with Robert Wagner and then in The Judge and Jake Wyler with Joan Van Ark. Neither film, however, became a series.

Two years after that, Davis made her Broadway comeback in a modernized version of The Grain is Green. The play was well attended, despite poor reviews. However, for Davis, who was 66 at the time, the strain of constant stage appearances was too much. Due to a back injury, she dropped out of the production.

After a year off from filming, Davis returned to the screen in 1976. She took supporting roles in the films Country House of Dead Souls with Karen Black and The Disappearance of Aimee with Faye Dunaway. Once again, controversy arose with the co-stars. Davis criticized especially the lack of respect towards her person and the lack of professional behavior on the set.

For television Davis got many role offers at this time, so she could decide for herself which she accepted and which not. She appeared in the television series The Dark Secret of Harvest Home (1978) and the Agatha Christie film Death on the Nile (1978), among others. She received an Emmy Award for her performance in Homecoming of a Stranger (1979) and other nominations for her performances in White Mama (1980) and Little Gloria - Poor Rich Girl (1982). Davis also appeared in two Disney films. Other television films with her included The Lady (1981) with her grandson J. Ashley Hyman, A Piano for Mrs. Cimino (1982) and At the End of the Road (1983) with James Stewart.

Last years of life

After Davis filmed the pilot episode for the television series Hotel in 1983, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Later in the hospital, a stroke paralyzed the right side of her face and her left arm, and also severely limited her speech. She then began a lengthy course of physical therapy. After some improvement in the paralysis, she returned home, but broke her hip in a fall.

The relationship between Davis and her daughter B. D. Hyman deteriorated during this time, as Hyman wanted to introduce her mother to the Christian revival movement. Davis traveled to Britain after her recovery to star in the Agatha Christie film Murder with a Double Bottom (1985), and learned upon her return that Hyman was planning to publish a biography.

The book was later titled My Mother's Keeper and describes in chronological order events of a difficult mother-daughter relationship, written by a daughter who suffered from her mother's domineering ways and drunkenness. Several friends and followers of Bette Davis described the experiences described as incorrect, and Mike Wallace arranged for a rebroadcast of a 60 Minutes interview with B. D. Hyman that had been recorded several years earlier. There, the latter testifies that she adopted many of Davis' mothering skills for herself and applied them in raising her own children. Even Davis' ex-husband Merrill let it slip in a CNN interview that Hyman's motives were "cruelty and greed."

Davis' second autobiography, titled This 'N That, concludes with an open letter to her daughter. In it, she accuses Hyman of "a great lack of loyalty and gratitude for the extremely privileged life I feel I have given you." The letter ends with an allusion to her daughter's book, "If money is the issue and my recollections are correct, I have been your protector all these years. And I add that my name made your book about me a success." Davis never spoke to her daughter again for the rest of her life and promptly disinherited her.

Davis subsequently appeared in the television film All Summers Die (1986) and Lindsay Anderson's Whales in August (1987), in which she played Lillian Gish's blind sister. The film earned mostly appreciative reviews. Her final role was as Miranda Pierpoint in Larry Cohen's Dance of the Witches (1989). However, her health did not allow her to finish the film, and instead Barbara Carrera's role was given more space in the film. Dance of the Witches was not released until after Davis' death.

During the 1989 American Cinema Awards, Davis collapsed. She had to acknowledge that the cancer had returned. Nevertheless, she traveled to Spain to accept an honor at the Festival Internacional de Cine de Donostia-San Sebastián. While there, her health deteriorated rapidly. Physically unable to make the trip home to the United States, she went to France, where she died on October 6, 1989, at the American Hospital in Neuilly-sur-Seine. She was buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park next to her mother Ruth and sister Bobby. Her epitaph reads "She did it the hard way." This saying was suggested to her by Joseph L. Mankiewicz shortly after the filming of All About Eve was completed.

Davis with Ronald Reagan (1987)

Bette Davis together with Elizabeth Taylor (1981)

Bette Davis Foundation

In 1997, Davis' executor Michael Merrill, her son, and her former assistant Kathryn Sermak established the Bette Davis Foundation to support young actors and actresses through college scholarships. Each year since 1999, the Foundation has honored a Boston University College of Fine Arts acting student with the Bette Davis Award and a scholarship. The most famous recipient to date is Ginnifer Goodwin, who received the award in 2001 and starred in the six-time Oscar-nominated 2005 film Walk the Line.

At irregular intervals, the Bette Davis Foundation presents the Bette Davis Lifetime Achievement Award. Meryl Streep received the award in 1999, Prince Edward in 2002 and Susan Sarandon in 2008. On the occasion of Davis' 100th birthday, Lauren Bacall received the Bette Davis Medal of Honor. In 2014, Geena Davis was honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award.

Search within the encyclopedia