Yiddish

Yiddish (Yiddish יידיש or אידיש, literally Jewish, short for Yiddish-Daitsch or Jewish-German; obsolete Jewish German, called Judendeutsch) is an approximately thousand-year-old language that was spoken and written by Ashkenazi Jews in much of Europe and is still spoken and written by some of their descendants today. It is a West Germanic language that evolved from Middle High German and has, in addition to High German, a Hebrew-Aramaic, a Romance, and a Slavic component. From more recent times there are influences from New High German and, depending on where the speakers live today, also from English, Iwrith and other coterritorial languages. Yiddish is divided into Western and Eastern Yiddish. The latter consists of the dialect associations Northeastern Yiddish ("Lithuanian Yiddish"), Central Yiddish ("Polish Yiddish") and Southeastern Yiddish ("Ukrainian Yiddish").

The Yiddish language spread throughout Europe in the Middle Ages, first in the course of Eastern settlement and later also as a result of the migration of Jews from German-speaking areas due to persecution, especially to Eastern Europe, where Eastern Yiddish eventually emerged. With the waves of emigration of millions of Eastern European Jews in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it then spread westwards and reached the new Jewish centres in America and Western Europe, and later also Israel.

Yiddish was one of the three Jewish languages of Ashkenazi Jews, along with Hebrew and Aramaic, which were largely reserved for writing. It was used not only as a spoken language, but also as an everyday language written and printed with Hebrew characters. Judeo-Spanish plays a role similar to that of Yiddish for Ashkenazi Jews for Sephardic Jews.

While Western Yiddish began to die out as early as the 18th century, Eastern Yiddish remained the everyday language of the majority of Jews in Eastern Europe until the Holocaust destroyed the Jewish centers of continental Europe. Today, Yiddish is still spoken as a native language by (often elderly) descendants of Eastern European Jews, by a small but active number of so-called Yiddishists, and especially by ultra-Orthodox Ashkenazi Jews. The number of native speakers is estimated at a maximum of one million.

Because speaking, writing, and cultural creation in Yiddish since the late 18th century has been almost exclusively on an Eastern Yiddish basis, Yiddish today is understood to mean Eastern Yiddish in fact, as long as Western Yiddish is not explicitly mentioned. In this article, therefore, East Yiddish is the focus of the description.

Present distribution

Today, in some traditional, ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities, such as especially in New York (in the borough of Brooklyn) as well as in the New York suburbs of Kiryas Joel, New Square, and Monsey, in Montreal as well as in its suburb of Kiryas Tosh, in London, in Antwerp, and in Jerusalem (such as in the borough of Me'a Sche'arim) and surrounding areas, there are larger groups of speakers who use Yiddish as an everyday language and pass it on to the next generation. In addition to these speakers, there is also a small secular community of speakers who continue to maintain Yiddish.

According to a 2015 estimate by Ethnologue, there are 1.5 million speakers of Eastern Yiddish, whereas Western Yiddish is said to have just over 5,000 speakers today. The figures for Western Yiddish, however, are open to interpretation and are likely to relate almost exclusively to people who have only residual competence in Western Yiddish and for whom Yiddish is often part of their religious or cultural identity.

In the Swiss Surbtal, whose West Yiddish dialects are generally counted among those that were still spoken the longest, Yiddish died out as a living language in the 1970s. In Alsace, where Western Yiddish has probably persisted longest, there are said to have been a few speakers of this linguistic variety as late as the beginning of the 21st century. The loss of this traditional language has hardly been noticed by the public.

Today there are a total of six chairs of Yiddish Studies, two of them in Germany (Düsseldorf and Trier). At other universities, language courses and exercises are offered, mostly within the framework of Jewish Studies.

Scripture

Yiddish is written with the Hebrew alphabet (Alyamiado spelling), which has been adapted for the special purposes of this non-Semitic-based language. Thus, certain characters used for consonants in Hebrew are also used for vowels in Yiddish. German- and Slavic-based words (with very few exceptions) are written largely phonetically, while Hebrew- and Aramaic-based words (also with few exceptions) are written largely as in Hebrew. Unlike Ladino (Judeo-Spanish), Yiddish is very rarely written in Latin letters - usually only when the text is addressed to a readership that does not (fully) understand Yiddish.

There are several transcriptions in Latin script, which are equivalent if they grant a one-to-one correspondence between character and sound and can thus be converted into each other without any problems. The transcription developed by the YIVO in New York, which is partly based on the English spelling, is internationally widespread in YIVO-affine circles. In the German-speaking world, this English basis is often replaced by a German one; instead of y, z, s, v, ts, kh, sh, zh, ay, ey, oy, j, s, ß (or ss), w, z, ch, sch, sh, aj, ej, oj are used. Finally, in linguistics, a transliteration is often used instead of a transcription; for y, ts, kh, sh, zh, tsh, ay, ey, oy of YIVO, one uses j, c, x, š, ž, č, aj, ej, oj.

Hebrew characters and Latin transcription

| Characters | YIVO transcription | German-basedTranscription | linguistictransliteration | Name |

|

|

|

| shtumer alum | |

| a | a | a | pasekh alef | |

| o | o | o | comets alef | |

| b | b | b | beys | |

| v | w | v | veys | |

| g | g | g | giml | |

| d | d | d | daled | |

| h | h | h | hey | |

| u | u | u | vov | |

| u | u | u | melupm vov | |

| z | s | z | zayen | |

| kh | ch | x | khes | |

| t | t | t | tes | |

| y | j | j | yud | |

| i | i | i | khirek yud | |

| k | k | k | kof | |

| כ ך | kh | ch | x | khof, long khof |

| l | l | l | lamed | |

| מ ם | m | m | m | mem, shlos mem |

| נ ן | n | n | n | well, long now |

| s | ß, ss | s | samekh | |

| e | e | e, e ~ ə | ayin | |

| p | p | p | pey | |

| פֿ ף | f | f | f | fey, long fey |

| צ ץ | ts | z | c | tsadek, long tsadek |

| k | k | k | kuf | |

| r | r | r | reysh | |

| sh | sch | š | shin | |

| s | ß | s | sin | |

| t | t | t | tof | |

| s | ß, ss | s | sof |

| Yiddish special characters (digraphs) | ||||

| Characters | YIVO- | German based transcription | linguistictransliteration | Name |

| v | w | v | tsvey vovn | |

| zh | sh | ž | zayen-shin | |

| tsh | tsch | tš | tes-shin | |

| oy | oj | oj | vov yud | |

| ey | ej | ej | tsvey yudn | |

| ay | aj | aj | pasekh tsvey yudn | |

The schtumer alef ("silent aleph", א) stands in non-Semitic words before all onset vowels (also diphthongs) except ajen (ע) and of course not before alef (אָ ,אַ): So one writes אײַז (ajs "ice"), אײ (ej "egg"), איז (is "is"), אױװן (ojwn "oven"), און (un "and"), but ער (er "he"), אַלט (alt "old"), אָװנט (ownt "evening"). This is also true (with the exception of the Soviet spelling variant) within compounds, e.g. פֿאַראײן (farejn "club") or פֿאַראינטערעסירן זיך (farintereßirn "to find interest in something"). In more traditional orthography outside YIVO orthography, the schtumer alef is also used as a sound separator and letter separator; YIVO orthography uses punctuation instead. An example of the former is רואיק (ruik "quiet", written according to YIVO רויִק, thus with dotted jud), two examples of the latter װאו (wu "where", written according to YIVO װוּ) and װאוינען (wojnen "dwell", written according to YIVO װוּינען; so both with dotted wow).

Transcriptions in the comparative text

Two sentences from Awrom Sutzkewer's story "Griner Akwarium" serve below as a demonstration of the YIVO and German-based transcriptions as well as a scientific transcription:

YIVO-Transcription: Ot di tsavoe hot mir ibergelozn mit yorn tsurik in mayn lebediker heymshtot an alter bokher, a tsedrumshketer poet, mit a langn tsop ahinter, vi a frisher beryozever bezem. S'hot keyner nit gevust zayn nomen, fun vanen er shtamt.

German based transcription: Ot di zawoe hot mir ibergelosn mit jorn zurik in majn lebediker hejmschtot an alter bocher, a zedrumschketer poet, mit a langn zop ahinter, wi a frisher berjosewer besem. ß'hot kejner nit gewußt sajn nomen, fun wanen er schtamt.

Transliteration: Ot di cavoe hot mir ibergelozn mit jorn curik in majn lebediker hejmštot an alter boxer, a cedrumšketer poet, mit a langn cop ahinter, vi a frišer berjozever bezem. S'hot kejner nit gevust zajn nomen, fun vanen er štamt. (The stressed and unstressed /e/ sound can, moreover, be distinguished according to 'e' and 'ə').

Translation: this very legacy was left to me years ago in my lively hometown by an old bachelor, a confused poet with a long braid in the back, similar to a broom made of fresh birch twigs. No one knew his name, his origins.

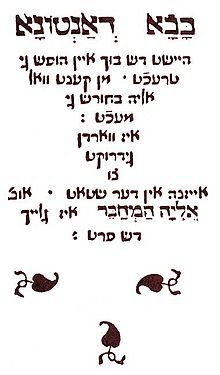

"Bovo d'Antona", later "Bowe-book" or "Bowe-majße" by Elia Levita from 1507/1508, first printed edition from 1541: the first completely preserved non-religious Yiddish book. The folk-etymologically reinterpreted expression "bobe-majße", invented story, literally "grandmother story", goes back to the title.

Search within the encyclopedia