World War II

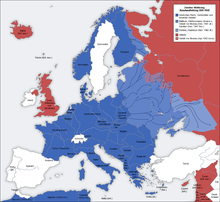

The Second World War (1 September 1939 - 2 September 1945) was the second global war waged by all the great powers in the 20th century. In Europe, it began on 1 September 1939 with the invasion of Poland ordered by Adolf Hitler. In East Asia, the Empire of Greater Japan had already been engaged in the Second Sino-Japanese War with the Republic of China since July 1937 and in a border war with the Soviet Union from mid-1938. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in early December 1941 resulted in the entry of the United States into the Second World War and the beginning of the Pacific War, in which the European colonial powers also became involved. In the course of the war, two military alliances were formed, known as the Axis Powers and the Allies (Anti-Hitler Coalition). The main opponents of the Nazi German Reich in Europe were the United Kingdom, headed by the war cabinet of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and (from June 1941) the Soviet Union, under the dictatorship of Joseph Stalin. Many historians today argue that the Second World War only became a world war with the entry of the USA, as this in 1941 linked the previously regional wars in Asia (1937) and Europe (1939).

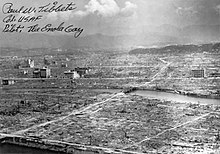

With the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht, hostilities in Europe ended on 8 May 1945; the two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki led to Japan's surrender on 2 September 1945 and thus to the end of the war.

More than 60 states around the world were directly or indirectly involved, and more than 110 million people were under arms.

The numbers of casualties in the war can only be estimated. More than 60 million people were killed in the fighting on land, at sea and in the air war. Estimates that include victims of the Holocaust (Shoa), Porajmos and other mass murders, forced labour and war crimes and consequences of war range up to 80 million.

In Europe, the Second World War consisted of blitzkriegs, campaigns of conquest against neighbouring German countries with the incorporation of occupied territories, the establishment of puppet governments and area bombardments. In the territories conquered by the Axis powers and also in Germany, an increasingly strong resistance to National Socialism formed during the war years.

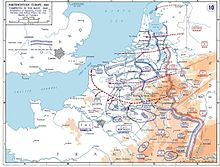

For the German Wehrmacht, the course of events in the theatres of war in Europe and the Mediterranean can be divided chronologically into three main phases:

- First phase: attacks on Poland, Denmark/Norway, the Benelux countries and France, the Balkans and North Africa.

- The second phase began with the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941.

- The third phase followed in the west with the Allied landings in Normandy on 6 June 1944. In the east, the Red Army opened its successful Operation Bagration about two weeks later.

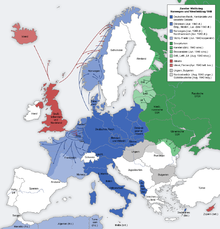

Six European states remained officially neutral and did not participate directly in the fighting: Ireland, Sweden, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal and Turkey (the latter until February 1945). The US government of President Franklin D. Roosevelt had declared US neutrality at the beginning of the European war, but from November 1939 the new Neutrality Act and the cash-and-carry clause allowed belligerent states to buy weapons and ammunition in the United States and transport them away on their own ships. Direct deliveries by the USA were made possible by the Lend-Lease Act passed in February 1941. In August 1940, the US Congress gave its approval for the construction of a large fleet to be deployed in the Atlantic and the Pacific.

With the entry into the war of Fascist Italy, ruled by Benito Mussolini and allied with the German Reich, parts of East and North Africa as well as the Mediterranean region also became the theatre of war from June 1940. In the East African campaign, Italian troops fought against British units for the colony of British Somaliland. In the parallel African campaign, the German Afrika Korps supported the Italians from February 1941. After the two battles at El-Alamein in July 1942 and October/November 1942, Anglo-American troops landed in Morocco and Algeria (Operation Torch) and the German and Italian troops had to surrender after the Tunisian campaign in May 1943.

The war against the Soviet Union was waged by the German Army, Waffen-SS and Luftwaffe as a war of extermination with the intention of winning Eastern Europe as far as the Urals as a (new) German settlement area for a future "Greater Germanic Reich". The great turning point in the war was the fighting around Moscow (winter 1941/1942) and the futile attempt to conquer Stalingrad from autumn 1942 onwards. The west bank of the Volga at Stalingrad marked the easternmost point of the German advance on the Eastern Front. After the victory in the Battle of Stalingrad, the Red Army counterattacked - from 1943 to the end of 1944, the occupied territories of the Soviet Union were gradually recaptured by the Red Army. With the destruction of Heeresgruppe Mitte in the summer of 1944, German defeat was inevitable. The German army units retreated to what were then the eastern borders of the Reich. The joint attack by the Western powers (Great Britain, the USA and Canada) on three fronts in Europe - the landing on Sicily (July 1943), the landing in Normandy (June 1944) and the landing in southern France (August 1944) - formed a step towards a foreseeable end to all fighting in Europe.

After the Western Allies crossed the German western border in the Aachen area in October 1944 and the Red Army crossed the eastern border in East Prussia, fighting began on German territory. In their winter offensive of 1945, Red Army troops reached the Oder River on a broad front and opened the battle for Berlin in mid-April. On 25 April 1945, US troops clashed with Soviet troops on the Elbe. After Hitler committed suicide in the Berlin Führerbunker on 30 April 1945, the German troops in the city surrendered two days later. On 8 May 1945, Field Marshal Keitel signed the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht; the war in Europe was thus ended. The end of the war was celebrated by the victorious powers with several parades, including the Moscow Victory Parade of 1945 and the Berlin Victory Parade of 1945.

The Empire of Japan, which had been allied with the German Empire and Italy in a three-power pact since 1940, had destroyed most of the US Pacific fleet in the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. The USA now declared war on Japan, which was followed by declarations of war on the USA by Germany and Italy. The USSR remained neutral towards Japan for the time being in accordance with the neutrality pact of 13 April 1941.

At the Arcadia Conference in Washington (December 1941/January 1942), the USA and Great Britain decided to defeat Germany first as the most dangerous opponent ("Germany first"). But from 1942 to 1945, protracted fighting also took place in East Asia (China, Burma, British Malaya, Thailand, French Indochina, Dutch India), the Philippines and many islands in the Pacific (including New Guinea). The Japanese troops were able to occupy many of the European colonies and other countries such as Thailand and the Philippines by mid-1942. It was not until the Battle of Midway in early June 1942, in which the Imperial Japanese Navy lost four of its six large aircraft carriers, that the tide turned in the Pacific War. The Allied soldiers were subsequently able to occupy even smaller Pacific islands in "island jumping", often only with great losses. To hasten the end of the fighting in East Asia, the new US President Harry S. Truman ordered in July 1945 that one atomic bomb each be dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On 2 September 1945, the Second World War ended with Japan's surrender.

"This war was a historically unprecedented attack on humanity, a destruction of all the cultural ideals that the Enlightenment had produced, a crash the likes of which had never been seen before. It was Europe's Armageddon." In addition to the loss of human life, many historic districts and buildings were irretrievably lost through the destruction of entire cities. This loss was followed by the reconstruction of affected European cities, whose cityscapes would be as if changed by war and new construction.

As a result of the Second World War, the political and social structures throughout the world also changed. The United Nations Organisation (UNO) was founded, whose permanent members in the Security Council became the main victorious powers of the Second World War: USA, Soviet Union, China, Great Britain and France. The European colonial powers Britain and France lost their overseas possessions and most of their colonies became independent. "Only with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the end of the Cold War did the phase of history marked by the Second World War [...] come to an end."

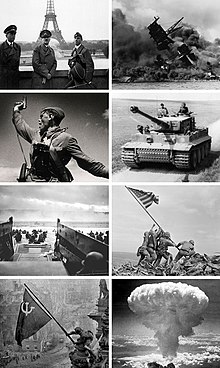

Impressions from the Second World War: Albert Speer, Adolf Hitler, Arno Breker in front of the Eiffel Tower, June 1940 - sinking "USS Arizona" after the attack on Pearl Harbor, 7. 12. 1941 - Soviet battalion commander leading the attack with his pistol, 12. July 1942 (photo by Max Alpert) - German tank "Tiger", March 1944, Northern France - landing of the 1st US Infantry Division, 6 June 1944 at Omaha Beach - GIs raising US flag, 23. 2. 1945, Iwojima - Soviet flag on the Reichstag, May 1945 - atomic mushroom cloud of "Fat Man" over Nagasaki, 9. 8. 1945

Previous story

→ Main article: Prehistory of the Second World War in Europe and Prehistory of the Second World War in the Pacific Region

In the years from 1920 to the end of the Second World War in 1945, fascism or right-wing extremism increasingly gained political dominance in large parts of Europe. In Italy, Benito Mussolini was already given power in 1922 with the March on Rome. In Germany, National Socialism grew into a mass movement after 1930. On 30 January 1933, it and its right-wing conservative allies were handed political power when Reich President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Reich Chancellor. The latter formed Hitler's cabinet from National Socialists and German Nationalists.

The revision of the international order after the Treaty of Versailles, already a goal of earlier German governments, was part of the programme of the National Socialists and their allies. With the unification of the Saar region with the German Reich in 1935 and the reintroduction of compulsory military service (also in 1935), the invasion of the demilitarised Rhineland in March 1936, the "Anschluss of Austria" (March 1938) and the separation of the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia in the Munich Agreement (30 September 1938), the Versailles peace order was gradually dissolved. This was facilitated by the British and French appeasement policy, which aimed at a peaceful understanding with National Socialist Germany. After the "break-up of the rest of Czechoslovakia" in March 1939, only the British and French governments protested. Shortly afterwards, Lithuania returned the Memelland to Germany under the pressure of circumstances. The First Slovak Republic became a German vassal state, closely bound to Germany by a "protection treaty". Great Britain and France wanted to limit German expansionist ambitions and issued a declaration of guarantee for Poland on 31 March 1939, which was converted into a formal alliance a short time later.

As early as October 1935, Italy, which maintained close relations with the German Reich, attacked Ethiopia and occupied Albania on 7 April 1939.

In the Spanish Civil War, a Popular Front government led mainly by Republicans, Socialists and Communists and supporters of a military revolt led by General Francisco Franco fought each other from 1936 to 1939. The Soviet Union and the French Popular Front supplied the "Popular Front" with weapons and war material. Italy and Germany supported Franco's Nationalist troops. The German government sent the Condor Legion for this purpose, the Italian the Corpo Truppe Volontarie (CTV), which contributed decisively to the victory of Francoism.

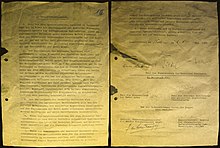

On 23 August 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union surprisingly concluded a "non-aggression treaty between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics", later called the "Hitler-Stalin Pact". In a secret additional protocol, it was decided to divide Europe into geographically precisely designated but otherwise undefined "spheres of interest". This ultimately amounted to the division of Poland between Germany and the Soviet Union and the unilateral conquest and occupation of further territories (including the Baltic states and parts of Finland and Greater Romania) by the USSR.

In the Munich Agreement (September 1938), Germany, Great Britain, France and Italy agreed on a peaceful solution to the Sudeten crisis, although Hitler would have secretly preferred a warlike solution even then.

The Japanese expansionist policy began in the 1930s, when the influence of the military leadership on the imperial government grew stronger. Japan saw itself as a protective and regulatory power, destined to dominate the other East Asian peoples. The raw material deposits and the reservoir of labour offered by the neighbouring countries were to benefit the Japanese economy. The main interest was initially the Republic of China, whose heavily industrialised region of Manchuria had already been annexed in 1931 and declared a protectorate of Manchukuo. In response to international protests, Japan withdrew from the League of Nations in 1933. At the end of 1936, Germany and Japan concluded the Anti-Comintern Pact. In mid-1937, Japan started the Second Sino-Japanese War.

From left: Chamberlain, Daladier, Hitler, Mussolini and Count Ciano, Munich 29 September 1938

Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler shortly after their arrival in Munich, 28 September 1938

War aims and conduct of the great powers

The possibility that a full-scale war could occur was taken into account by the great powers, so they made preparations accordingly. The preparations for war therefore included, for example, the stockpiling of resources and goods essential for war and the expansion of civil defence programmes.

Axis powers

Germany

In the European context, the Second World War was a war of robbery, conquest and extermination launched by National Socialist Germany with the long-term goal of creating an unassailable German empire of conquered and dependent territories. From the beginning, the goal was German world power and the "racist reorganisation of the [European] continent". In the process, classical power-political motives were mixed with racial ideological ones. These included, on the one hand, the acquisition of "living space in the East" with resettlement or extermination of the predominantly Slavic peoples living there who were considered "racially inferior", and, on the other hand, the "final solution of the Jewish question". Both were justified by the anti-Semitic idea of a "Jewish Bolshevism" as part of a conspiracy of "world Jewry", which in the form of the Soviet Union was seen as a threat to the foundations of life of the "Aryan race" and the European civilisation represented by it.

According to the will of the National Socialist leadership, the ethnic group of Slavs was first to be subjugated and the conquered Eastern Europe was to be made usable by German settlers, so-called military farmers (cf. map on the right). After the destruction of their elite, the Slavic peoples were to provide forever a reservoir of uneducated and subservient agricultural and unskilled labourers. The European part of the Soviet Union was to be divided into territories under the direction of imperial commissars. Only White Russians, Ukrainians and Baltic peoples were considered worthy of living. According to Alfred Rosenberg, "Russianness [...] would certainly face very difficult years".

The German strategy envisaged the use of a politically and temporally limited opportunity for a strategic offensive. It pursued military, racial-hegemonic, economic and diplomatic goals. In military terms, the blitzkrieg was intended to enable a rapid and extensive gain of space in order to pre-empt the emerging superiority of the enemy's armament. This strategy thus represented a special manifestation of the war of movement in combination with the decisive battle, which drew on German experience in the First World War. In economic terms, it was intended to conserve resources so as not to burden industrial capacities to the detriment of the consumer economy. There was to be no discontent among the German population because of a possible material shortage. In order to secure the "home front" and in the sense of making the best possible use of the conquered capacities, a two-front war was initially avoided, but on 31 July 1940, at the Berghof near Berchtesgaden, Hitler announced to his generals the most serious decision he had taken during the Second World War: "In the course of this conflict, Russia must be finished off. Spring 1941." (Entry in Halder's war diary, 31 July 1940). Thirdly, the plundering of the occupied territories, especially in East-Central and Eastern Europe, the enslavement of their inhabitants for the benefit of the German Reich and its "Aryan" population was intended to realise the racially motivated hegemonic ideas of National Socialism. The diplomatic acquisition of European and non-European allies was intended to secure this hegemonic position.

The indignation over the Treaty of Versailles, especially the harsh and perceived unjust demands for reparations and the one-sided apportionment of blame to the Central Powers resonated with large sections of the German population. The revision of the Treaty of Versailles and the return of the German Reich to the circle of the great powers had always been sought with particular vigour by the German generals, the monarchist and anti-republican part of the German bourgeoisie and the economic elite. For the National Socialists, they were merely a stage goal.

In August 1936, in the secret memorandum on the Four-Year Plan, Hitler demanded the operational capability of the German army and the war capability of the economy within four years in order to achieve a wartime "expansion of the living space or the raw material and food base" for the German Reich. On 5 November 1937, he specified his war aims before the military and foreign policy leaders of the Reich. He rejected autarky and Germany's return to world trade; only the acquisition of a larger living space was a way out. His unalterable decision was to solve the German spatial question by 1943/45 at the latest.

After 13 October 1943, the day the Badoglio government in Italy declared war, the German Reich was in a state of war with 34 states and had only the Empire of Japan as a notable ally. These two states, independently of each other, were fighting a hopeless war against the rest of the world. A further 18 states declared war on the German Reich by March 1945. Germany's previous allies in south-eastern Europe, Hungary and Romania, dropped out in 1944. Finland signed a separate armistice with the USSR on 19 September 1944. Bulgaria was occupied by the Red Army in September, although it was not in a state of war with the Soviet Union. In Serbia, Croatia, Macedonia and Montenegro, "people's governments" were formed in December 1944, after the Red Army had occupied Belgrade at the end of October 1944 and Tito had reached an agreement in Moscow on how to proceed. After the withdrawal of the Wehrmacht, a communist government led by the partisan supremo Enver Hoxha was formed in Tirana on 10 November 1944.

Italy

After the First World War, the Treaty of Saint-Germain gave Italy Veneto, Istria, Trentino and the German-speaking South Tyrol. In October 1935, it invaded the Empire of Abyssinia (today Ethiopia) and annexed the country. This annexation, which was contrary to international law, was part of Mussolini's declared goal of resurrecting the Roman Empire. After the annexation of Austria to the German Reich in March 1938, Mussolini took a clear position in favour of Nazi Germany. Without informing Hitler in advance, he had Albaniaoccupied in early April 1939, claiming that this was the counterpart to the German annexation of the Czech Republic some four weeks earlier. In the so-called Steel Pact of May 1939, Mussolini bound himself contractually to Hitler and the German Reich. With Italy's declaration of war on France and Britain, the country entered the war in Europe on 10 June 1940, because Mussolini's false speculation led him to believe that the war was as good as over. The Three-Power Pact at the end of September 1940 created the Berlin-Rome-Tokyo axis between Germany, Italy and Japan. Less than a year later, Mussolini also joined the German war against the Soviet Union on 23 June 1941. Four days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Germany and Italy declared war on the USA. After the landing of British and American troops on Sicily in July 1943, the inner-party opposition in the Grand Fascist Council outvoted Mussolini and had him arrested after a subsequent visit to King Victor Emmanuel III. Italy left the Axis alliance after the Cassibile Armistice and re-entered the war on the side of the Allies.

Japan

Since its modernisation in the course of the Meiji Restoration in the years 1868 to 1877, the Japanese Empire had been striving for territorial expansion on the Asian continent, primarily to secure important raw materials. These goals focused particularly on the Republic of China, which was considered weak. Encouraged by an expansionist dynamic, Japan saw the increasing tensions in Europe as an opportunity to counter the growing influence of the USA in the western Pacific Ocean (Commonwealth of the Philippines and US outer territories). Geostrategic considerations were compounded by the frequent interference of the armed forces in the affairs of civilian leadership and a mutual cultural aversion between broad segments of the population in Japan and the United States.

Japan, similar to the German Empire in Europe, was faced with a deteriorating strategic position in East Asia over the years. The main cause was its isolation in alliance politics. The predominantly US-American unwillingness to accept Japanese expansion in the region was basically joined by China, the Soviet Union and the European colonial powers. Specifically, the Japanese Empire saw itself threatened in a fourfold geostrategic context. To the east was the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, to the north the Soviet Union, to the west China, and to the south/southwest, in addition to the Philippines under US leadership, British Malaya and North Borneo, French Indochina and the Dutch Indies. In addition, Australia, which belonged to the British Commonwealth, with its mandate territory "Territory of New Guinea" was suitable as a base of operations against Japan due to its spatial expansion and location.

This geostrategic starting position prompted the Japanese leadership, like the German, to mix diplomatic instruments with a war of movement. After a failed advance into Soviet territory in 1938/39, it therefore concluded a neutrality pact with the USSR in April 1941. The attack on Pearl Harbor by the Imperial Japanese Naval Air Force, whose build-up was qualitative in view of the restrictions of the Washington Naval Agreement, intended above all to deal a decisive blow to the United States Navy in view of its increasing armament. In Southeast Asia itself, Japan also concentrated in the first step on neutralising concentrated military resources, such as the build-up of long-range B-17 bombers on the islands of the Philippine archipelago. The subsequent Japanese invasion of Southeast Asia served to procure raw materials, primarily oil, and was intended to cut off the USA's supply route to Australia.

Allied

Western powers

On the Western Front, the war plans of the Western powers, similar to those of the First World War, essentially envisaged an attrition of the German army. This was to be supplemented by bombing the major cities and blockading the German economic cycle.

Soviet Union

The communist leadership saw the Soviet Union surrounded by a capitalist world that was hostile in principle and considered war inevitable. For them, it was a matter of delaying the war until the five-year plans had created the potential to stand up to a confrontation. But this goal did not preclude an offensive in order to throw one's own weight decisively into the balance when the opportunity arose. With the German-Soviet non-aggression pact, Stalin believed that he had prevented joint action by the capitalist powers against the Soviet Union and could assume the role of a spectator to the self-destruction of capitalism for a longer period of time.

After the start of Operation Barbarossa, the Soviet Union consciously appropriated lessons from the preceding German rearmament. On land, it followed the German example of the Army Group, whose core consisted of mobile and heavily armoured divisions, and established centrally coordinated air fleets that enabled targeted close air support through significant improvements in the flow of information. After the preceding, politically motivated decimation of the officer corps, Stalin delegated operational leadership to Marshal Georgi Konstantinovich Zhukov, whose above-average skills enabled the successful command of several million men.

Comparison of military potentials

Size of the armed forces (in millions):

| Year | GB | USSR | USA | D.R. | Japan | Italy |

| 1939 | 0,48 | 1,60 | 0,60 | 4,52 | 1,60 | 1,74 |

| 1940 | 2,27 | 5,00 | 0,70 | 5,76 | 1,70 | 2,34 |

| 1941 | 3,38 | 7,10 | 1,62 | 7,31 | 1,63 | 3,23 |

| 1942 | 4,09 | 11,34 | 3,97 | 8,41 | 2,84 | 3,81 |

| 1943 | 4,76 | 11,86 | 9,02 | 9,48 | 3,70 | 3,82 |

| 1944 | 4,97 | 12,23 | 11,41 | 9,42 | 5,38 |

War economy

→ Main article: War economy in the Second World War

"War economy in the Second World War" was the conversion of national economies into a centrally administered economy through the total mobilisation of economic resources to secure material supplies for the army and food for the population in order to achieve the war aims in the Second World War at any cost. In the process, market mechanisms were undermined. While the respective military tactics were decisive in the beginning, the quantitative superiority of the Allies' war production significantly influenced the course of the war from 1942 onwards. Nazi Germany and Japan pursued blitzkrieg tactics, for which a high utilisation of existing industrial facilities was supposed to be sufficient to produce a wide range of modern weapon systems (broad armament) and were not prepared for a prolonged war. The Allies' aim was to win the Second World War in the manner of a war of attrition. Since 1928, the Soviet Union had systematically brought about a highly standardised mass production of weapons (deep armament). After the war began, Great Britain and the USA had also begun to favour the war economy over the consumer goods industry in the allocation of scarce resources such as materials, personnel and means of production. Only after the obvious failure of the Blitzkrieg strategy did a reorganisation of the war economy take place in the German Reich and Japan from 1942 onwards, which then led to production levels similar to those of the Allies (armament miracle). In 1944, war goods production accounted for 40% of gross national income in the USA, 50% each in Great Britain and Japan, and slightly more than 50% in the German Reich.

A common war strategy was also to cut off the opposing parties from raw material and food imports. The German Reich developed great ingenuity in replacing scarce raw materials with "home materials". Additional non-ferrous metals such as copper, brass, tin, zinc, etc. that were important for the war were procured via the "metal donation of the German people".

The war economy in the Second World War led to a significant expansion of women's labour, especially among the Allies. Forced labour was widespread in the German Reich, Japan and the Soviet Union.

Armament production in the Second World War:

| Sector | GB | USSR | USA | D.R. | Japan | Italy |

| Tank | 28.500 | 110.000 | 91.270 | 61.250 | 7.200 | light Pz(**) |

| Aircraft | 133.000 | 162.000 | 329.000 | 126.000 | 90.000 | k. A. |

| Artillery | 36.400 | 541.900 | 219.000 | 101.200 | k. A. | k. A. |

| Warships | 1.340 | 260 | 8.950 | 1.540(*) | 625 | k. A. |

(*) without submarines

(**) mainly Fiat-Pz with 2-cm-cannon

Fleet comparison (1939/41):

| Ship type | GB | USSR | USA | D.R. | Japan | Italy |

| Battleships | 15 | 1 + 2 (in B.) | 17 + 15 (in B.) | 4 | 10 + 3 (in B.) | 4 + 4 (in B.) |

| Armoured ships | - | - | - | 3 | - | - |

| Aircraft carrier | 7 | - | 7 + 11 (in B.) | - | 8 + 8 (in B.) | - |

| Heavy cruiser | 15 | 6 + 4 (in B.) | 18 + 8 (in B.) | 3 | 18 + 18 (in B.) | 8 |

| Light cruisers | 41 | - | 19 + 32 (in B.) | 6 | 20 + 17 (in B.) | 14 |

| Flak cruiser | 8 | - | 4 + 2 (in B.) | - | - | - |

| Minelayer cruiser | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Destroyer | 113 | 81 | 171 + 188 (in B.) | 22 | 108 + 108 (in B.) | 128 |

| Torpedo boats | - | 269 | - | 20 | - | 62 |

| Submarines | 65 | 213 | 114 + 79 (in B.) | 62 | 63 | 115 |

US war poster: "We cannot win this war without also making sacrifices on the home front".

Japanese soldiers occupy the Forbidden City in Beijing, 13 August 1937

The Concept of the General Plan East, 1940 - 1943

War in Europe

→ Main article: Chronology of the Second World War, a day-by-day timeline

From the Invasion of Poland to the Defeat of France, September 1939 to June 1940

In the first phase of the war, Germany (coming from the west) and the Soviet Union (coming from the east) conquered and occupied Poland (from 1 and 17 September 1939 respectively), Germany conquered Denmark and Norway (April-June 1940) and the Netherlands, Belgium and France (May-June 1940). The rapid defeat of France was unexpected by most people, not least Josef Stalin. Nevertheless, Hitler did not achieve his main goal of keeping Britain out of the war, forcing her to surrender or defeating her militarily. This became clear at the latest in October 1940 during the air battle over Britain. Great Britain remained the only state that was consistently a capable opponent of Germany from the beginning of the war.

German invasion of Poland, 1939

→ Main article: Invasion of Poland

Hitler had set the attack for 4:30 a.m. on August 23, but withdrew the order at short notice the previous day after learning that Italy was not ready for war and that England and Poland had fixed their mutual commitments by treaty.

Hitler now ordered the Wehrmacht to attack Poland at 4:45 a.m. the following day on 31 August 1939. This directive also contained tactical instructions for the behaviour of the Wehrmacht in the west and north (Baltic Sea entrances Kattegat and Skagerrak) and forbade attacks against "the English motherland" with insufficient partial forces.

This military invasion of the neighbouring country was not preceded by a formal declaration of war. In order to justify the invasion of Poland, the German side faked several incidents, such as the fake attack on the Gliwice radio station by SS members disguised as Polish resistance fighters on 31 August. They announced in Polish over the radio that Poland had declared war on the German Reich. The flimsy trick was triggered from Berlin with the password "Grandmother died". Almost three million German soldiers had marched up to invade Poland. They had around 400,000 horses and 200,000 vehicles at their disposal. 1.5 million men had advanced to the Polish border, many with blanks to pretend they were just going on manoeuvres. The ambiguity ended, however, when they were ordered to load live ammunition.

The military attack was launched by the German liner Schleswig-Holstein on the Polish position "Westerplatte" near Danzig and the Luftwaffe with the air raid on Wieluń on 1 September 1939. The Polish army with about 1.01 million soldiers faced 1.5 million German soldiers. Technically and in terms of warfare, it was inferior. After the invasion of eastern Poland by the Red Army on 17 September 1939, the balance of power was once again dramatically shifted in favour of the aggressors. On the other hand, the Polish government counted on the support of France and Great Britain, which had issued an ultimatum to the German Reich on 2 September on the basis of the "Declaration of Guarantee of 30 March 1939". It demanded the immediate withdrawal of all German troops from Poland. The British-French guarantee declaration would have obliged these states to launch their own offensive in western Germany no later than 15 days after a German attack. Hitler assumed that the two Western powers would let him have his way, just as they had done with the invasion of "Remnant Czechoslovakia", and left the West Wall only lightly manned.

There was no attack by the Western powers, but Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September after the ultimatum had expired. However, Chamberlain's wartime government lasted only seven months, during which time Britain remained largely passive in the sit-down war.

By means of concentrated attacks within the framework of a "Blitzkrieg" strategy, the Wehrmacht succeeded in encircling large sections of the Polish defenders and winning encirclement battles such as those at Radom (9 September) and on the Bzura (until 19 September).

On the night of 17 September, after the Wehrmacht had crushed organised Polish defences, the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland began in accordance with the secret additional protocol of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact. The next day, the Polish government fled Warsaw for Romania via south-eastern Poland. On 28 September, President Ignacy Mościcki resigned from office in exile in Romania. It was not until 18 December 1939 that the new Polish government-in-exile declared a state of war with the Soviet Union. Great Britain and France did not join in.

Warsaw was the target of intensive air raids from 20 September until the surrender, which cost the lives of 25,000 civilians and 6,000 soldiers. The bombing was carried out with maximum force because Hitler wanted to demonstrate what could also hit French and British cities. On 26 September, about 120,000 Polish soldiers surrendered in the capital Warsaw, after being surrounded by German troops on 18 September. The Modlin fortress was surrendered on 29 September after a 16-day siege. Poland's last troops surrendered on 6 October after the battle of Kock.

On 8 October, the German Reich and the Soviet Union divided the conquered territory along a demarcation line in the Brest-Litovsk Agreement, which went down in history as the "Fourth Partition of Poland". Not only were the territories ceded under the Treaty of Versailles reincorporated into the Reich, but in addition large areas of central Poland including the city of Łódź. The rest of Poland became a German Generalgouvernement, "administered" from Krakow.

The subsequent occupation period was marked by extreme reprisals by the occupiers against the civilian population. Deportations for forced labour were only the most visible manifestation; Jews in particular became victims of the National Socialist racial and extermination policy. In the eastern part of Poland, numerous "class enemies" were deported to the Gulag by the Soviet occupiers; the military elite was "liquidated" at Katyn and elsewhere.

The tactics of the attack on Poland, designed for a quick victory - and successful in this - promoted the use of the term "Blitzkrieg" and shaped Germany's further warfare until the end of 1941.

War of Position on the Western Front, 1939

→ Main article: Seat war

On 3 September, France and Great Britain declared war on Germany. As a result, a limited and rather symbolic offensive by the French against the Saar region began on 5 September. The Germans offered no resistance and retreated to the heavily fortified Westwall. After that, things remained quiet on the Western Front. This phase is also referred to as the "Sitzkrieg". Apart from isolated artillery skirmishes, there were no Allied attacks. On the German side, the propaganda machinery started rolling. With leaflets and slogans over loudspeakers, the French were asked "Why are you waging war?" or proclaimed "We will not shoot first".

On 27 September, Hitler issued an instruction to the Army High Command to draw up a plan of attack, the so-called "Fall Gelb". By 29 October, the plans had been completed. They provided for two army groups to advance through the Netherlands and Belgium in order to crush all Allied forces north of the Somme.

In the end, however, no attack took place in 1939, as bad weather conditions and much greater losses in Poland than expected (22% losses in fighter planes, 25% in tanks) caused the attack to be postponed a total of twenty-nine times. In addition, several senior officers of the Army High Command, which was stationed in Zossen near Berlin, had urged the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Colonel General Walther von Brauchitsch, to oppose a premature deployment of the Army against France. On 5 November, he warned Hitler not to underestimate the French. Moreover, German troops had proved poorly trained in the invasion of Poland. Hitler was beside himself and wanted to hear examples. Brauchitsch was not prepared for this. Hitler threw the humiliated general out with the remark that he knew "the spirit of Zossen" and was ready to "destroy it". Chief of General Staff Franz Halder feared that his coup plots would be exposed, and the actual opponents of the regime, essentially the group of younger officers in the OKH, abandoned their coup plans.

Finnish-Soviet Winter War, December 1939 - March 1940

→ Main article: Winter War

Since the beginning of the 1930s, Finland had adapted to the level of development of the other Nordic democracies, with which it was confessionally related through its Protestant-Lutheran character. In the field of foreign policy, they moved closer together when Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark as well as Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands joined together in the autumn of 1933 to form the so-called Oslo States, which professed a close customs union. In 1935, the Finnish government of Toivo Kivimäki committed itself to closer cooperation with the three other Scandinavian states in order to secure their common neutrality.

On 30 November 1939, Soviet troops under the command of Marshal Kirill Merezkov crossed the Finnish border in the so-called Winter War. The Red Army attacked with 450,000 men, 2,000 tanks and 1,000 aircraft, expecting a quick victory. Their officers assumed that the Finns would welcome them as their brothers and liberators from the capitalist oppressors. The Soviet leadership underestimated the fighting strength of the Finns, who with only 200,000 soldiers, including many reservists and youth, a few tanks and planes were able to prevent the Red Army attackers from breaking through the Mannerheim Line after heavy Soviet losses. Finnish soldiers used simple but effective incendiary devices to fight tanks, which they called "Molotov cocktails" after the Soviet Union's foreign minister. The numerical superiority of the Soviet troops did not have much effect because the forest terrain and deep snow hardly permitted Red Army operations off the few roads and often only one regiment could fight at the front on paved roads. These adversities were compounded by temperatures of minus 35 °C. At the end of the Winter War, the Red Army had more than 85,000 dead and missing, the Finnish Army about 27,000 men. The Finnish army was supported by 12,000 volunteers from Sweden, although Swedish military officials had advised against it. Only after extensive regrouping and reinforcements was the Red Army able to achieve major breakthroughs on the Karelian Isthmus west of Lake Ladoga in early February 1940.

Sweden indirectly supported Finland without giving up its neutrality. Great Britain and France did not intervene in the war in favour of the Finns, as both states did not want to have another enemy in the war. The German Reich sympathised with Finland, but military support was not given because of the existing non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union.

The peace treaty signed on 12 March 1940 stipulated that Finland had to cede large parts of West Karelia and the northern half of Lake Ladoga to the Soviet Union. In direct response to the Soviet attack, Finland took part in the German war against the Soviet Union in 1941 in the Continuation War to recapture the lost territories. A significant consequence of the Winter War was also that Stalin began a reorganisation of the Red Army, rehabilitating officers who had been exiled to Siberia in the course of the Great Terror. This reorganisation contributed significantly to the Red Army having more fighting strength in 1941 than the German Army High Command had assumed. In 1947, Finland also had to cede Petsamo to the Soviet Union. At the end of the war, the Finns had lost just under 27,000 soldiers in the fighting, while the Red Army had lost almost 130,000. After the end of the Continuation War, Finland also had to cede the Petsamo area on the Barents Sea to the Soviet Union in 1944. Finland thus lost its only year-round ice-free port.

Occupation of Denmark and Norway, April 1940

→ Main article: Enterprise Weser Exercise

At the end of 1939, after the loss of iron ore imports from France (Lorraine Minette), ore deliveries from neutral Sweden covered 49 percent of German demand. These were transported from the Swedish mining areas near Kiruna by ore railway to the year-round ice-free loading port of Narvik in Norway. Norway was therefore of extraordinary economic and military importance to the German Empire. Another important raw material was Finnish nickel. The British wanted to disrupt these important supplies of raw materials and stop them as soon as possible (→Altmark incident), which is why on 5 February 1940, the supreme Franco-British war council agreed to land four divisions in Narvik. On 21 February, Hitler issued a directive for the planning of operations in Scandinavia. On 1 March, it was decided to launch the Weserübung. It envisaged taking Denmark and using it as a "springboard" for the conquest of Norway. The first attacks on British warships took place in March.

On 5 April, the Allied Operation Wilfred began, in which the waters off Norway were to be mined and more troops brought into the country. One day later, the German Unternehmen Weserübung began. Almost the entire Kriegsmarine was mobilised and half of the entire German destroyer flotilla was sent to Narvik. On 9 April, a Mountain Infantry Division was landed in Narvik.

The British military leadership considered a German landing to be quite unlikely, which meant that only minor countermeasures were taken by the Allies. The Germans were able to expand their bridgehead without major resistance, so that on 10 April Stavanger, Trondheim and Narvik were already occupied, after Denmark had already been occupied without a fight. Great Britain occupied the Danish Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic on 12 April for strategic reasons.

In the attempt to occupy the capital Oslo, heavy units of the Kriegsmarine were deployed, which were ill-suited in the narrow waterway of the Oslo Fjord. In the process, the German flagship, the heavy cruiser Blücher, whose first combat mission was her last, was sunk by Norwegian coastal batteries. Oslo was taken by airborne troops later than the Germans had planned.

On 13 April, nine destroyers and the battleship HMS Warspite sank the remaining eight German destroyers still in the Ofotfjord off Narvik in a second British attack. Two Kriegsmarine light cruisers and numerous freighters were also sunk by British submarines and Royal Air Force aircraft.

On 17 April, the Allies finally landed at Narvik and put the Wehrmacht troops under heavy pressure with simultaneous massive shelling by Royal Navy ships. By 19 April, large Allied formations, including Polish soldiers and parts of the Foreign Legion, were landed in Norway. They captured Narvik and pushed the mountain troops of the Wehrmacht back into the mountains.

In the meantime, the weather in Norway improved so that the Wehrmacht could consolidate its fronts and a British and a French destroyer could be sunk during attacks by German aircraft off Namsos on 3 May.

In the same month, Churchill decided to withdraw the Allies from Norway because of the German successes in France. However, before the 24,500 soldiers could be evacuated, they still managed to enter Narvik and destroy the important harbour. On 10 June, the remaining soldiers of the Norwegian armed forces finally surrendered, whereupon the Weser Exercise was completed.

Norway under German occupation became a Reich Commissariat and part of the German territory, but Hitler wanted it to remain an independent state. In the further course, Norway was heavily fortified because Hitler feared an invasion. In February 1942, a puppet government was established under Vidkun Quisling.

Western campaign, May/June 1940

→ Main article: Western campaign

On 10 May 1940, the attack by German units ("Fall Gelb") began with a total of seven armies on the neutral states of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. 136 German divisions faced around 137 Allied divisions.

The Netherlands was the first to cease its resistance. On 13 May, Queen Wilhelmina and the government went into exile in London. After the rapid advance of Army Group A through the Grand Duchy and bombardment of Rotterdam, which killed 814 inhabitants of the city, the Dutch forces capitulated on 15 May 1940. Three days later, the former leader of the Austrian National Socialists, Arthur Seyß-Inquart, took office as Reichskommissar for the Netherlands. The Dutch islands of Aruba and Curaçao (South America) had great strategic importance during the World War because of their world's largest oil refineries, which is why they were shelled by German and Italian submarines in 1942.

The Belgian army resisted a little longer. By 16 May, the forts of Liège, Namur and the Dyle position had been taken, followed by Brussels on 17 May and Antwerp the next day. This enabled the German attackers to cut off the Belgian troops north of this line from the British and French formations, which in the meantime had advanced into Belgium. The Belgian government fled to Britain via France. On 28 May, King Leopold III, who remained in the country, signed the surrender against the will of the cabinet. Government President Eggert Reeder became head of the German military administration.

In order to bypass the northern section of the Maginot Line, neutral Luxembourg was used by the Wehrmacht as a transit area. Afterwards, the Grand Duchy became a so-called "CdZ area" under the control of a chief of the civil administration.

In France, the government and the military had relied on the heavily fortified Maginot Line along the Franco-German border from Basel to Luxembourg. Because the Belgian Ardennes were considered difficult for tanks to pass, the Allies considered them a natural extension of the Maginot Line. Lieutenant General Erich von Manstein's campaign plan, on the other hand, envisaged an advance through the Ardennes with six armoured and five motorised divisions to encompass the French and British troops at Boulogne and Calais from the south. Army Groups B and C were to act more defensively. This plan was helped by the fact that strong Allied forces, including the bulk of the British Expeditionary Force, were advancing far to the north to come to the aid of the hard-pressed Belgians and Dutch, thus leaving room for German troops of Army Group A in their rear. On 19 May, German units reached the Channel coast, about 100 km south of Calais. The advance further north along the Channel coast was so rapid that the British and French units were encircled at Calais and Dunkirk. This rapid and unexpected advance was later referred to by Churchill as the "sickle cut". Hitler, in agreement with von Rundstedt and contrary to the opinion of other generals, decided to spare the battered panzer force, halt its advance and leave the encirclement of Dunkirk to the Luftwaffe and the artillery regiments.

This gave the British three days to prepare for Operation Dynamo, which began on 27 May. About 1200 ships and (also private) boats were able to evacuate a total of 338,000 soldiers, including 145,000 soldiers from the French army. About 80,000 soldiers, mainly French, remained behind. The British had lost 68,000 men in the fighting. Almost all remaining tanks and vehicles, most of the artillery and existing supplies had to be destroyed. From a military point of view, Hitler's halting order, which allowed the evacuation of almost the entire British Expeditionary Corps, represented a grave tactical and, especially in retrospect, momentous mistake. The ability to continue the war would have become much more difficult for Britain after the loss of the Expeditionary Corps, as they were experienced professional soldiers. Thus, the Allies only lost the war material left on the beach, which could be more easily replaced. But Churchill's rousing speeches also invigorated British courage in May and June 1940 and strengthened the sense of what the war meant for the survival of freedom and democracy.

As the British retreated, France prepared to defend itself. The "Fall Red", the actual battle for France, began on 5 June with a German offensive on the Aisne and the Somme. On 9 June, German soldiers crossed the Seine. On 10 June Italy entered the war on Germany's side and on 21 June began an offensive in the Western Alps, although Pétain's government had asked Italy for an armistice on 20 June. On 14 June, parts of the 18th Army occupied the French capital, Paris. To prevent its destruction, it had been declared an open city and evacuated by French troops without a fight. On the same day, German troops broke through the Maginot Line south of Saarbrücken and the symbolic fortress of Verdun was also taken.

After German troops reached Orléans and Nevers on the Loire (260 km south of Paris) as well as Dijon on 17 June, a request for an armistice from Philippe Pétain, Prime Minister of the newly formed French government, arrived at Hitler's headquarters. The Führer was then praised by Keitel as "the greatest general of all time". Hitler met with Mussolini in Munich on 18 June to agree the armistice terms with him. Hitler rejected the Duce's far-reaching demands, including Nice, Corsica and Savoy as well as the use of ports and railways in Africa for military purposes. He was concerned to prevent the French fleet and the colonies from continuing the war. Nevertheless, Italy began an offensive in the Alps on 21 June, which resulted in only minor gains, including Mentone. The terms of the armistice were presented by Keitel to French General Charles Huntziger in the Compiègne carriage on 21 June 1940. On 22 June, the French delegation, having had almost all their counter-proposals rejected, signed the armistice treaty. It came into force at 01:35 on 25 June, after the Italian-French armistice had also been signed the day before. France was only allowed to maintain 100,000 soldiers with light weapons; artillery and tanks were not allowed. On 1 July 1940, the Wehrmacht demonstrated its victory over France with a grand parade on the Champs-Elysees in Paris.

The so-called "Blitzkrieg" in the West had lasted only six weeks and three days, in which about 100,000 French, 35,000 British and about 46,000 German soldiers lost their lives. French fighter pilots shot down several hundred German fighter planes and almost 1,000 German fighter pilots were taken prisoner. France was divided into two zones: The north and west of France were German-occupied; here were important airfields and naval bases (including Brest, Lorient, St. Nazaire, La Rochelle and Bordeaux) for the war against Great Britain.

The Wehrmacht attack prevented the execution of Operation Pike, which was in preparation, with which England and France wanted to destroy the oil sources of the Soviet Union in order to bring about a "complete collapse" of the Soviet Union.

Follow

Politically and strategically, the German Reich found itself in a situation after the victory in the West that opened up fundamentally new options for it to continue the war: for the war against Great Britain in the West, it had shifted the balances in the Mediterranean, and it was able to draw on the economic resources of Western Europe, Central Europe and Eastern Central Europe and thus sustain the war for a long time, including. These included industrial goods from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, iron ore from Sweden shipped to Germany via the Norwegian port of Narvik, agricultural products from Poland, Denmark, the Netherlands and Greece, industrial goods from Belgium and France, tungsten from Portugal and oil from Romania. Neutral Switzerland could be used for international money transactions and foreign exchange deals.

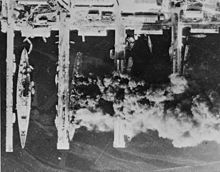

Three battleships of the French fleet anchored in Mers-el-Kébir were sunk or severely damaged by Royal Navy ships on 3 July 1940 on Churchill's orders, following a British ultimatum that remained unanswered, to prevent them from falling into German hands (Operation Catapult). This resulted in the deaths of 1297 French sailors. The eastern and southern parts of France remained under French control. Marshal Philippe Pétain ruled the so-called "État français" from Vichy as a puppet state of the German Empire.

In November 1942, the previously unoccupied zone was occupied by German and Italian troops after Anglo-American troops landed in North Africa. The 50,000 soldiers of the Vichy government offered no resistance to the Germans and Italians. The rest of the demobilised French navy was sunk by the crews in the port of Toulon.

From the Surrender of France to the Attack on the Soviet Union, June 1940 to June 1941

Despite France's capitulation, the war continued because Britain did not accept Hitler's so-called peace offer of 19 July 1940. Although the outcome of the war with Britain was still completely open, Hitler announced to the generals as early as 31 July his basic intention to have an attack on the Soviet Union prepared for 1941. Shortly afterwards, on 17 September, he postponed Unternehmen Seelöwe indefinitely.

Hitler sought to consolidate his rule over the "New Europe" and secure it through further alliances with Spain, France, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. Franco and Pétain opposed a formal alliance with Germany.

France libre

→ Main article: Forces françaises libres

Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970), previously military secretary of state, became an organiser of the resistance as the "leader of Free France" from exile in London. Mocked by the Vichy regime's propaganda as Le Général micro and Fourrier (rations sergeant) of the Jews, he called on his compatriots to resist. As early as 18 June 1940, he had addressed all French people in a radio speech: "France has lost a battle. But France has not lost the war!" He predicted that the industrial potential of the United States would turn the tide in this war. He thus rejected the opinion of defeatists that Britain would be defeated within three weeks.

Air Battle for England, 1940/1941

→ Main article: Battle of Britain

National Socialist propaganda referred to the preparations for an invasion of Great Britain by eliminating the Royal Air Force as the "Battle of Britain". Hitler did not believe in success and preferred a peace treaty with Great Britain, admittedly only if it would return the former German colonies and renounce influence in Europe.

In the two years between the Munich Agreement and the "Battle of Britain", the British had improved their air defences. Chain Home radar stations were installed on the south and east coasts of the British Isles. British industry was able to produce more than 1400 fighter planes in the three months before the start of the Second World War. The Royal Air Force (RAF) successfully recruited pilots from the Commonwealth, France, the USA, Poland and Czechoslovakia, as there were six German pilots for every RAF pilot. It was a similar story with the aircraft: In the Western campaign, there were about four German fighters and bombers for every British fighter. For this reason, Dowding also used foreign volunteers as fighter pilots, initially from the Commonwealth countries Canada, Australia and New Zealand, but then also from Poland, the Czech Republic and France. One fifth of the almost 3000 "Spitfire" or "Hurricane" pilots deployed in the Battle of Britain did not come from Great Britain.

On 2 July, Göring began the air battle with a limited offensive against shipping in the English Channel. Hugh Dowding, commander of the British air defence, did not accept the challenge. The next phase began in mid-August. The RAF was to be crushed by destroying its aircraft in the air, while the fight against shipping continued. In August and September, British fighters shot down 341 German aircraft and lost 108 themselves. The RAF had the advantage that the pilots of the downed aircraft were not lost to them every time, provided they managed to save themselves by parachute. In the next phase, the Luftwaffe concentrated its attacks on London. Hitler spoke of retaliation and total annihilation after 60 RAF bombers had flown a raid on Berlin on the night of 26 August on Churchill's orders, causing little damage. On 7 September, the Luftwaffe attacked the London docks with 300 bombers and 600 fighters, but again lost more aircraft than the British fighter squadrons. On 15 September, the German attacks, dubbed "The Blitz" by the British, peaked with two days of raids. The German bombers were decimated and the fighters repulsed. The decision to attack London is considered a major strategic mistake with far-reaching consequences, for further attacks on London until the end of the year with an average of 160 bombers achieved little, militarily speaking, but were extremely costly for the Luftwaffe. On 17 September 1940, Hitler postponed "Unternehmen Seelöwe" indefinitely.

The Luftwaffe continued its night raids throughout the winter and spring, not to prepare for invasion but to hit industry and demoralise the population. In the Luftwaffe attack on Coventry on the evening of 14 November 1940, factories such as Armstrong Siddeley's aircraft engine works were targeted, but incendiary and demolition bombs also hit three quarters of residential areas, killing 568 residents. The term "coventrieren", a coinage of the Reich Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, subsequently found its way into German military jargon.

In total, about 43,000 civilians lost their lives in air raids on London, Coventry and other British cities in 1940/41. In London alone, 14,000 people were killed in 57 night raids between 9 September 1940 and New Year's Day 1941. In October 1940, the Luftwaffe had lost 1733 fighter aircraft, the RAF 915.

"The air battle ended as a military stalemate, but was a political and strategic defeat of the first order for Hitler, who for the first time had failed to impose his will on a country." Contributing factors to the Luftwaffe's failure were the misjudgement of the effectiveness of the British radar systems and guidance system, and the lack of range of the German fighter planes. The British aircraft factories also produced more machines than the German ones.

With the end of the air battle, "the invasion was also over. On 18 December 1940, Hitler issued his formal instructions for Unternehmen Barbarossa, "to strike down Soviet Russia in a swift campaign even before the end of the war against England." Hitler's decision was also informed by "achieving final victory in the war by defeating London via Moscow". From May 1941 onwards, German air raids on Britain decreased significantly because bombers and fighter planes were needed for the imminent attack on the Soviet Union.

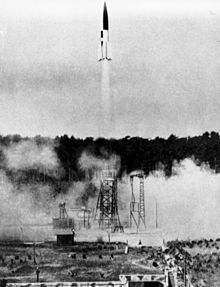

A total of 61,000 British lost their lives in German air raids, 8,800 of them in attacks with the "retaliatory weapons" V1 and V2.

Hitler's Alliance Policy

After the war enemy Great Britain could not be defeated, Hitler looked for a way out. In his mind, two possibilities presented themselves: an attack on British positions in the Mediterranean or an attack on the Soviet Union, whose exploitation as a "living space in the East" had long been an integral part of his ideology.

First, he turned to the Mediterranean option. In June 1940, Spain's dictator Franco was still prepared to enter the war on Germany's side. In return, he demanded Gibraltar, French Morocco, Oran and the expansion of the Spanish Sahara and Spanish Guinea colonies, as well as extensive deliveries of weapons, raw materials and food. Hitler did not consider Spain's support necessary at the time and made evasive replies. When he met with Franco in Hendaye on 23 October, however, Hitler showed a much greater interest in Spain's entry into the war, which he proposed for January 1941. Spanish and German troops could conquer Gibraltar and thus seal off the Mediterranean to the west. Foreign Minister Ribbentrop even went a step further and ventilated the idea of an anti-British continental bloc from Spain to Japan. Franco and Súñer, his son-in-law and later foreign minister, however, were no longer convinced that Britain would soon be defeated. They were not tempted to take rash steps and repeated deliberately exaggerated demands for the supply of arms. Hitler, in turn, had to be considerate of Vichy France with regard to Spanish colonial desires in North Africa. Franco therefore only agreed to sign a protocol in which Spain declared its willingness to become a member of the Three-Power Pact and to enter the war - with the reservation that the timing was still to be jointly agreed. This made the agreement practically worthless for Hitler. In the internal circle, he later "raged" about the "Jesuit pig" and the "false[n] pride of the Spaniard".

As in Hendaye with regard to Spain, it remained open in Montoire-sur-le-Loir at two meetings with Pétain and Laval on 22 and 24 October 1940 whether there would be concrete cooperation with France. Hitler wanted to achieve, if not a declaration of war on England, at least the defence of the French colonies in North Africa and the Middle East against attacks by the FFL and the British, as well as the surrender of bases on the African Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts for the naval war against Great Britain. Marshal Pétain agreed in principle to cooperation with Germany, but indirectly rejected France's entry into the war by having it pointed out that a declaration of war could only be made by parliamentary resolution. Such a decision was questionable. The result of the meeting was therefore meaningless for the war against Great Britain. Nevertheless, Pétain indicated in a radio speech a few days later that he would take the path of collaboration with Germany.

Italy had become Germany's wartime ally in June 1940, shortly before the French surrender. The Japanese ambassador Saburō Kurusu and the foreign ministers Galeazzo Ciano (Italy) and Joachim von Ribbentrop (Germany) signed the Three-Power Pact in Berlin on 27 September 1940, which provided for mutual assistance in gaining hegemony over Europe and East Asia respectively. The provisions were not directed against the Soviet Union; rather, the USA was to be deterred from entering the war. Although the pact was a great propaganda success, it had no immediate effect on the formation of an active front against Britain.

In Eastern Europe, Hitler gained Romania as an ally, which was extremely valuable to him because of its strategic location and the oil fields near Ploiești. It is true that he let the Soviet Union claim Bessarabia, which had been lost after the First World War, as provided for in the Hitler-Stalin Pact. But Hitler guaranteed Romania's existence in the summer of 1940, which in turn withdrew from the League of Nations.

Italian Parallel War in the Mediterranean and East Africa, 1940/1941

→ Main articles: Italian invasion of Egypt, East African campaign and Greece - from independence to the Second World War

Mussolini hoped that after the German Axis partner, Italy could also achieve military successes, although King Victor Emmanuel III had still made the realistic assessment in 1939 that the army was in a pitiful state and the officers were no good. After Italy entered the war on 10 June 1940, Mussolini ordered British positions in the Mediterranean and in North and East Africa to be attacked. After minor initial Italian successes in Egypt and East Africa, the initiative was lost in the late summer and autumn of 1940. Counter-offensives by British and Commonwealth forces (Operation Compass) led to Italian defeats in Egypt, the eastern part of Libya (Cyrenaika) and East Africa in early 1941.

130,000 Italian soldiers fell into British captivity. In February 1941, Hitler reacted by sending the German Africa Corps (Unternehmen Sonnenblume) to at least prevent Italy from losing the colony of Libya. In East Africa, Italy lost 30,000 soldiers (24,000 prisoners of war and 6,000 killed in action) and its colonies there by the end of November 1941.

Mussolini's great power ambitions had already been directed towards the Balkans since the 1930s. On 28 October 1940, Italian forces attacked Greece (Greek-Italian War). Mussolini believed in a quick victory; instead, the war turned into a fiasco. The Greek troops were well organised and knew their way around the difficult terrain of the Pindos Mountains. "Within a fortnight, the expected triumph had turned into a humiliation for Mussolini's regime" when the attackers had been pushed back beyond the borders of Albania.

More significantly, the Axis position in North Africa was seriously weakened because, in the face of the looming debacle, urgently needed Italian troops were transferred from there to Greece. Yet North Africa was of utmost importance: if the weak British troops had been driven out of Egypt and away from the Suez Canal, the world war would have taken a different course.

Balkan campaign, 1941

→ Main article: Balkan campaign (1941)

At the beginning of 1941, the German Reich tried to mediate in the Balkan conflict. Hitler proposed to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia that it join the Three-Power Pact, but this was rejected. Greece also renounced any attempt at mediation, as its army was able to force the Italian soldiers at the front to retreat. A major Italian offensive on 9 March turned into a disaster. On 27 March, Yugoslavia finally joined the Three-Power Pact. The result was anti-German demonstrations and a coup d'état by the Serbian officer corps against the government of Prince Regent Paul, whereupon the accession was reversed.

This unexpected turn of events led to Hitler's decision to attack Yugoslavia. He justified the attack as retaliation against a Serbian "criminal clique" in Belgrade. On 6 April, units of the Wehrmacht crossed the border into Yugoslavia and the Luftwaffe began to reduce Belgrade to rubble (→ Unternehmen Strafgericht), even though the capital had been declared an "open city". The further advance took place as if in a planned manoeuvre. On 10 April, Zagreb was occupied, where the Independent State of Croatia was proclaimed on the same day. Belgrade was occupied by German troops on 13 April. On 17 April, the Yugoslav commanders signed the surrender of the Yugoslav army.

The German campaign against Greece also began on 6 April. Unlike in Yugoslavia, the Greek resistance was extremely tough in places. Especially in the mountainous areas and in the area of the strongly defended Metaxas Line, German soldiers advanced only slowly and with heavy losses. On 9 April, Salonika fell. At the same time, the Greek army in eastern Macedonia was cut off and the Metaxas Line was pressed harder. The Greek reinforcements from the Albanian front were held up by German and Italian tank units and air attacks as they advanced through the mountainous countryside. On 21 April, 223,000 Greek soldiers were forced to surrender.

Meanwhile, the British units stationed in Greece built up a defence at Thermopylae. This was overrun on 24 April, whereupon the Allies had to launch an amphibious evacuation operation in which 50,000 soldiers were shipped to Crete and Egypt. On 27 April, the Wehrmacht entered Athens.

Hitler ordered on 25 April to conquer Crete with airborne troops, paratrooper units and the 5th Mountain Division in mid-May 1941. On 20 May 1941, German paratroopers landed on Crete. They suffered heavy losses in the process. The landed units were initially unable to capture airfields for supplies and reinforcements. Only through increased use of the Luftwaffe and after successful landings on contested airfields did the situation stabilise for the attackers. The Allies, including New Zealanders and Australians, defended Crete for a week until they had to withdraw to Egypt with about 17,000 men. Due to the high German losses, Hitler decided not to carry out any more air landings in the future. The attempt to conquer the strategically important island of Malta was therefore abandoned.

From the Emergence of the Eastern Front to the Western Front, June 1941 to June 1944

The intention to invade the Soviet Union was discussed by Hitler in a circle of the highest generals on 31 July 1940 - in parallel with the invasion plans against Great Britain. At that time, Hitler still hoped that Britain would give up sooner or later and that, on the basis of an "understanding with England", he could throw all his strength eastwards to tackle his great goal of conquering "Lebensraum in the East". If Russia was defeated, then England's last hope was extinguished. On 18 December 1940, the order was given to attack the Soviet Union in May 1941. The background to this decision was also the realisation of the impossibility of landing on the British island as long as the air force and navy were too weak to do so. Even if not the sole motive, the desire to force London to withdraw from the war via Moscow was behind it. An attack on the Soviet Union was considered by Hitler to be of little risk because he completely underestimated the political stability of the Soviet Union and its military potential. To Mannerheim, in a confidential conversation in Finland on 4 June 1942, which was recorded without Hitler's knowledge, he openly admitted this underestimation. Hitler was not alone in his misjudgement of Soviet military potential; almost all his commanders shared it as well. On 30 March 1941, he announced to more than 200 senior officers in the Reich Chancellery that the forthcoming war was a race-ideological war of extermination and was to be waged without regard to the norms of international law. The commanders would have to overcome any personal remorse. In the East, "harshness is mild for the future." None of those present took the occasion to raise Hitler's demands for discussion again afterwards.

With the attack on the Soviet Union, Unternehmen Barbarossa, a new front emerged in eastern Germany on 22 June 1941. It became the longest-lasting front in the Second World War (along with the Japanese-Chinese front), which claimed the most victims. The German troops conquered huge areas of the European part of the Soviet Union; together with immediately following units of the SS and Einsatzgruppen, they had the task of ruthlessly exploiting the areas, killing part of their inhabitants and forcing the others into forced labour. In the process, many tens of thousands of Jews were systematically killed.

Six months later, Hitler's declaration of war made the USA, which had already indirectly supported Great Britain, Germany's official enemy. America needed time to adjust its economy to the war. A confrontation of the Wehrmacht with Anglo-American land forces took place for the first time in November 1942 in North Africa (Operation Torch).

War against the Soviet Union, June 1941 to October 1942

→ Main article: German-Soviet War

The Balkan campaign had postponed the time for an attack on the Soviet Union by four weeks. The attack did not take place until 22 June 1941. Although calculations on the German side showed that it was only possible to supply the Wehrmacht up to a line along Pskov, Kiev and the Crimea, Hitler demanded the conquest of Moscow as part of a single, uninterrupted campaign. This showed his dangerous underestimation of the Soviet Union, which had already been expressed after the surrender of France in June 1940 (see above). Three army groups (North, Centre, South) were ready for the invasion. Army Group North (von Leeb) was to conquer the Baltic states and then advance to Leningrad. The main burden lay on the Central Army Group (von Bock). It was to advance towards Moscow and was equipped accordingly. Army Group South (von Rundstedt) was to conquer the Ukraine. From occupied Norway, attacks were also launched against the Soviet Union. They targeted Murmansk, the harbour and the railway connection there, the "Murman Railway". The campaign also involved 600,000 soldiers from allied, neutral and occupied states. Later, 30,000 volunteers from neutral and occupied territories (among others Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Russia, Caucasus) joined, mostly representatives of radical right-wing or fascist currents in their home countries.

In the early morning of 22 June 1941, between 3:00 a.m. and 3:30 a.m., the attack against the Soviet Union began. Although he had received several serious indications, including from Harro Schulze-Boysen, Arvid Harnack and Richard Sorge, Stalin remained convinced that Hitler would not attack the Soviet Union before defeating Britain. The attack was led by 153 German divisions, including 19 armoured and 12 motorised divisions, over a front length of 1600 km between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathian Mountains. Two divisions operated from Finland. Army Group North occupied the three Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and reached Novgorod in early September. Army Group Centre reached Smolensk, on the direct route to Moscow, in the same period. Army Group South had the task of conquering Ukraine and at the same time was just outside Zaporozhye in south-eastern Ukraine. The Red Army's military commanders were not prepared for this largest military offensive in world history to date, involving just over three million army soldiers. Within a week they were joined by soldiers from the allied states of Romania, Italy, Slovakia and Hungary, as well as Finland, which had no alliance with Germany and made a point of stating that it was waging a "war of continuation" against the Soviet Union to recapture the territories it had ceded in 1940. The Red Army had nearly three million soldiers stationed on its western border, whose tanks, artillery and aircraft far outnumbered the attackers but were not ready for battle. Many of the Soviet soldiers on the border surrendered without resistance, while the motorised German troops were initially able to advance swiftly. The ability of the Soviet forces at that time to wage an attack or war against Germany must be strongly doubted, even according to more recent findings. The first Wehrmacht report on the morning of 22 June 1941, on the other hand, gave the impression that Soviet troops had entered East Prussia. It thus supported the preventive war legend of Nazi propaganda, which portrayed the attack as a defensive war. In fact, the invasion of the Soviet Union was essentially a war of conquest and extermination dressed up ideologically, with the goal of gaining "living space in the East" formulated by Hitler years earlier. This meant "a blockade-proof large empire" as far as the Urals and beyond the Caucasus.

On 22 June at noon, the Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov read out a speech on the radio in which he announced the outbreak of war. It was not until eleven days later that Josef Stalin addressed the people in a radio speech on 3 July. Before that, Minsk had been surrounded and occupied a little later. For a long time, Hitler insisted to the OKH on the priority of conquering Ukraine instead of Moscow. The main aim of the Nazi leadership was to secure the oil reserves of the Caucasus and the grain in the Ukraine. This, Hitler believed, would make them invincible. Despite victorious encirclement battles, the Barbarossa plan failed as early as August 1941, triggering the so-called "August Crisis" because large parts of the enemy escaped from these battles and regrouped, the surprise effect of the invasion wore off, German losses increased and Hitler's "zigzag of orders" to focus on Army Group Centre or Army Group South became more frequent.

Only after the capture of Kiev and Kharkov was the advance on Moscow resumed on 2 October. But already in October it began to rain, and in November frost set in with minus 22 degrees Celsius. As a result, the German offensive slowed down, becoming increasingly bogged down in mud or snow, and the attack on Moscow came to a halt on 5 December due to arctic temperatures of up to minus 50 °C and the stiffening Soviet resistance. The following day, a Soviet counter-offensive with units from the Far East, well equipped for winter warfare, began under the command of Zhukov, preventing the capture of the capital Moscow by German troops. The flight of the army group could be stopped by an unconditional halting order by Hitler, but his goal of "throwing down the Soviet Union in a swift campaign" had failed, "Barbarossa" had failed. The lost battle for Moscow was the geopolitical turning point of the Second World War, "the real caesura", because the series of German lightning victories came to an end. The Wehrmacht lost about a third of its soldiers by the end of January 1942. Only half of the one million killed, missing or wounded could be replaced. The Red Army suffered even heavier losses, with around 3.3 million prisoners, an unknown number of dead and 2.2 million wounded and sick.

In the Continuation War, Finland attempted, with German support, to recapture the territories in Karelia lost to the Soviet Union in the Winter War. After achieving this goal in the summer of 1941, however, Finland did not remain defensive, but occupied disputed Karelian territories that had never before been Finnish until December 1941.