World War I

The First World War was fought from 1914 to 1918 in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, East Asia and on the oceans. About 17 million people lost their lives in it. It began on July 28, 1914, with Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia, preceded by the Sarajevo assassination on June 28, 1914, and the resulting July Crisis. The armed conflict ended with the Compiègne Armistice on November 11, 1918, which was tantamount to the victory of the wartime coalition that emerged from the Triple-Entente. Major participants in the war were the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria on the one hand, and France, Great Britain and its British Empire, Russia, Serbia, Belgium, Italy, Romania, Japan and the United States on the other. 40 states took part in the most extensive war in history up to that time, and a total of nearly 70 million people were under arms.

In the Sarajevo assassination, the Austrian heir to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife Sophie Chotek, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated by Gavrilo Princip, a member of the underground revolutionary organization Mlada Bosna, which was or had been linked to Serbian officials. The main motive was the desired "liberation" of Bosnia and Herzegovina from Austro-Hungarian rule with the aim of unifying the southern Slavs under the leadership of Serbia.

For action against Serbia, Austria sought the backing of the German Empire (Hoyos Mission), since intervention by Russia as a protecting power had to be expected. Kaiser Wilhelm II and Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg pledged their unconditional support to Austria-Hungary in early July. The issuance of this so-called blank check marked the beginning of the July crisis. On July 23, Austria-Hungary ultimatively demanded that Serbia conduct a judicial investigation against the participants in the June 28 plot involving imperial and royal organs. organs. This was rejected by the Serbian government, encouraged by Russia's promise of military support in the event of conflict, as an unacceptable encroachment on its sovereignty. Russia's attitude, which was partly determined by the pan-Slavic motive, was again supported by France in the course of the French state visit to St. Petersburg (July 20-23), which, reaffirming the French-Russian alliance, guaranteed the Russians support in the event of war with Germany. On July 28, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia.

The interests of the great powers and German military planning (Schlieffen Plan) caused the local war to escalate within a few days to a continental war with the participation of Russia (German declaration of war on August 1, 1914) and France (German declaration of war on August 3, 1914). The political consequences of the Schlieffen Plan - bypassing the French belt of fortifications between Verdun and Belfort, German troops attacked France from the northeast, violating the neutrality of Belgium and Luxembourg - led to the entry of the Belgian guarantor power Great Britain and its dominions into the war (British declaration of war of August 4, 1914), which led to its escalation into a world war.

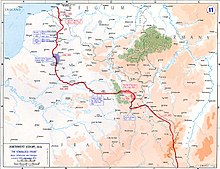

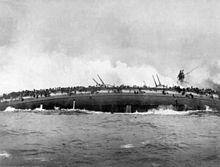

The German advance came to a halt at the Marne in September, and between November 1914 and March 1918 the front in the west stiffened. Since Russia continued to participate in the war in the east until the October Revolution of 1917 and the separate peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Germany found itself in a two-front war for a long time, contrary to planning. Typical features of the fighting included positional and trench warfare as well as material battles with high casualties and mostly only minor gains in terrain. This was the case, for example, in the Battle of Verdun, the Battle of the Somme, eleven of the twelve battles in the Isonzo and the four battles in Flanders. The gas war, the unrestricted submarine warfare - which resulted in the U.S. entering the war against the Central Powers in 1917 - and the Armenian genocide, which was related to the war effort, are considered special escalation stages.

Russia's withdrawal from the war effort after the Separate Peace with the Bolsheviks made possible the ultimately unsuccessful German Spring Offensive of 1918, but supply shortages resulting from the British naval blockade, the collapse of the allies, and developments on the Western Front during the Allied Hundred Days Offensive led the German military leadership to assess that the German front had become untenable. On September 29, 1918, contrary to all previous pronouncements, the Supreme Army Command informed the German Emperor and the government of the hopeless military situation of the army and, through Erich Ludendorff, made an ultimate demand for the opening of armistice negotiations. On October 4-5, 1918, Reich Chancellor Max von Baden petitioned the Allies for an armistice. By seeking the hitherto avoided, almost hopeless decisive battle with the Grand Fleet in the spirit of an "honorable demise" with the fleet order of October 24, 1918, the naval command aroused the resistance of sailors, who refused the order in growing numbers and as a result triggered the November Revolution. On November 11, 1918, the Compiègne Armistice came into effect. The terms of peace were settled in the Paris Suburban Treaties between 1919 and 1923. Of the losing powers, only Bulgaria was able to retain its pre-war state structure; the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire disintegrated; in Russia, the Tsardom declined; and in Germany, the Empire.

The First World War was a breeding ground for fascism in Italy, National Socialism in Germany and thus became the precursor of the Second World War. Because of the dislocations that the First World War triggered in all areas of life and its consequences, which have continued to have an impact into the recent past, it is considered the "primordial catastrophe of the 20th century". It marks the end of the age of (high) imperialism. The question of who was to blame for the outbreak of this war is still the subject of controversial debate today, and the corresponding Fischer controversy has in the meantime become part of German history. In the cultural sphere, the First World War also marked a turning point. The many thousands of front-line experiences in the trenches, the mass deaths and the upheavals in everyday life caused by hardship changed the standards and perspectives in the societies of the countries involved.

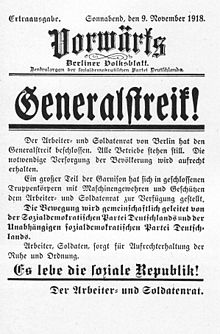

Against the backdrop of defeat, the November Revolution develops out of the Kiel sailors' uprising: issue of Vorwärts, November 9, 1918

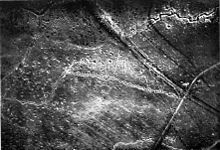

The Chateau Forest (Schlosswald) near Ypres consisted of nothing but tree stumps after the intense artillery bombardments (1917). Large parts of Belgium and northern France were devastated during the war

Tanks gained increasing importance from 1917 onwards despite technical problems and were essentially only available to the Allies: British Mark IV during the Battle of Cambrai

Air warfare became more and more important in the course of the war, but was not yet a decisive factor in the war as a whole (Photo: 1917/18)

Trench warfare was characteristic of the Western Front: British soldiers of the Royal Irish Rifles in a trench on the Somme, autumn 1916.

Artillery played a decisive role in the war effort: here a British 60-pounder cannon at Cape Helles, Gallipoli (1915)

The decisive battle at sea expected by all sides failed to materialize. Submarine warfare developed into the most significant aspect of naval warfare in World War I and was a major reason for the United States entering the war

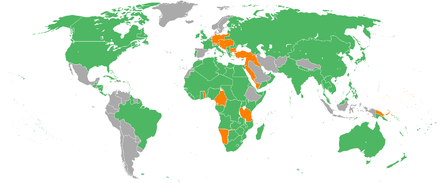

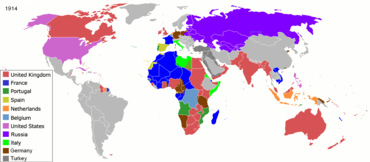

World War I - participating states Entente and Allies Central Powers Neutral

| The assassination in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914 - on the left in a not entirely accurate contemporary depiction - was followed by the July crisis and mutual mobilizations, on the right by the order for French mobilization on August 2, 1914 | ||

Previous history and initial situation

High Imperialism

Before 1914, Europe was at the height of its global dominance. As a result of the industrial revolution and population explosion, Europe, together with the powers Japan and the USA, which had also been acting imperially since the end of the 19th century, had succeeded in establishing global political domination (colonialism). Essentially, only China was able to maintain its independence; before 1914, only the U.S. and the Spanish colonies on the American double continent and, with restrictions, some white dominions succeeded in decolonizing. The establishment of the French protectorate over Tunisia (1881) and the British occupation of Egypt (1882) had given imperialism a new quality insofar as the European states again increasingly sought formal rule over newly acquired territories. This became visibly a matter of national prestige, as the strength of European states seemed to be defined in the public perception by their non-European position. Inevitably, this shifted the tensions that had arisen in the periphery back to the continent, especially when, in the 1890s, the division of the world was essentially completed without Italy and the German Empire having received a share commensurate with their self-image.

Crises

With the founding of the German Empire, an imbalance had arisen within the European pentarchy; the German Empire emerged from what had previously been the weakest power (Prussia). The German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine permanently stood in the way of an understanding with France. Security interests, national prestige and economic interests clashed more intensely in this constellation of powers. Apart from that, domestic tensions and fears of threats contributed to the fact that the ruling elites and governments were inclined toward a risky policy in order to distract attention from internal deficiencies through foreign policy successes. Thus, in the age of imperialism, peace-threatening crises increasingly developed:

- In the war-in-sight crisis (1875), Russia and Great Britain made it clear that they would not accept a renewed defeat of France. Without being involved in alliance systems, these powers reacted according to their great power interests, as they did later in the July crisis.

- In the Balkan crisis (1875-1878), a local conflict developed into a small-scale war (Serbian-Ottoman War) and from this the Russian-Ottoman War of 1877/78. The Congress of Berlin ended the crisis, but in the process deepened the rivalry of Austria and Russia in the Balkans and worsened German-Russian relations.

- French Boulangism exacerbated tensions between Germany and France (exemplified in the Schnäbele affair of 1887), especially during Georges Boulanger's tenure as minister of war (January 1886 to May 1887), and led to the revival of revanchism.

- The Bulgarian crisis - namely the Serbian-Bulgarian War of 1885/87 - significantly worsened Austro-Russian relations.

- The Fascoda Crisis (1898) and the Second Boer War (1899-1902) "signaled the filling of colonial power vacuums overseas [...] by European-North American imperialism around 1900, so that tensions on the periphery returned to Europe."

- In the First Moroccan Crisis (1904-1906), Germany tried to break France, isolated by Russia's weakness (Russo-Japanese War 1904/05, Russian Revolution 1905), out of the Entente cordiale, but failed at the Algeciras Conference (1906). On the contrary, the attempt led to the unmistakable isolation of the German Empire, which subsequently became all the more closely tied to Austria-Hungary.

- The naval battle at Tsushima (May 27, 1905) and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904/05, which Russia effectively lost, brought about a reorientation of Russian policy. After the loss of the East Asian position and in view of the British position in the Middle East, the urge to expand the zones of influence was oriented back to Europe and especially to Southeastern Europe, which brought about the conflict with Austria-Hungary.

- The Bosnian annexation crisis of 1908-09 fueled Serb nationalism. The wider political repercussions also led to the humiliation of Russia, which almost resulted in a war with the League of Two. In response to the annexation, the Mlada Bosna group was formed to carry out the Sarajevo assassination with the support of the Black Hand secret organization.

- Britain, mobilized by the Second Moroccan Crisis (1911), warned an increasingly politically isolated Germany against war against France. In view of the diplomatic failure (Morocco-Congo Treaty) despite German threats of war, the pressure of imperialist-oriented agitational associations - such as the Alldeutscher Verband and Deutscher Flottenverein - on the German emperor and his government, which had backed down, grew.

- The two Balkan wars strengthened Serbia, deepened tensions in the Danube monarchy, exacerbated the Austro-Russian antagonism, and further fueled Slavic nationalism.

- The Liman-von Sanders crisis of 1913/14 intensified Russia's distrust of Germany in particular.

Alliance system

The alliance system sought by Bismarck after the founding of the empire attempted to isolate France. This required good relations with Austria-Hungary and Russia (Three Emperors' Agreement of October 22, 1873). The Balkan crisis caused this agreement to effectively fail, and Germany's mediation in the Berlin Congress (concluded with the Treaty of Berlin on July 13, 1878) perceived Russia as hostile. The following year, Tsar Alexander II issued a more or less veiled threat of war in case of a repeat, so Bismarck looked for other allies. Further tensions with Russia developed as a result of Germany's grain tariff policy from 1879. Austria-Hungary and Germany concluded the Dual Alliance (October 7, 1879), which Italy joined in 1882 (Triple Alliance); Romania also joined in 1883. The treaty pledged mutual support in the event of a simultaneous attack by two other powers on a signatory or a French attack on the German Empire or Italy. The avoidance of European war by the Congress of Berlin thus led to the first permanent alliance between great powers since the Crimean War. This was joined on June 18, 1881, by the Dreikaiserbund, a secret neutrality agreement (German Empire, Austria-Hungary, and Russia) that broke down, however, in the Bulgarian crisis of 1885/87. Bismarck's dismissal in March 1890 marked the end of his alliance policy. Wilhelm II, on the recommendation of Bismarck's successor Leo von Caprivi and on that of the Foreign Office, then refrained from extending the secret reinsurance treaty between Germany and Russia concluded on June 18, 1887, which is considered one of the fatal decisions of the "New Course." Due to the German Lombard ban of 1887, which prevented the purchase of Russian railroad bonds in Germany, Russia increasingly oriented its financial policy toward France from 1888 onward. In 1891, France and Russia concluded an initially vague agreement, which was supplemented by a military convention in 1892 and ratified by Tsar Alexander III in 1894 (French-Russian Alliance). Britain, after abandoning its Splendid isolation, initially worked toward an alliance with Germany, which failed in the negotiations of March 29-May 11, 1898.

The Faschoda crisis (1898) initially led to a fierce Franco-English confrontation, which was resolved in the Entente Cordiale (April 8, 1904), which settled the general conflicts of interest over Africa's colonies ("Race for Africa"). Great Britain then drew closer to France, as Germany refused to renounce its naval armament, resulting in the Anglo-German naval arms race. The underlying Tirpitz Plan was based on risk theory. Germany believed it could pursue a free-for-all policy. The resulting intransigent German attitude toward arms limitations in the Hague Peace Conferences reinforced the general distrust of German policy. Britain, increasingly alarmed by German naval policy, gave France almost unreserved support during the Algeciras Conference (1906). Germany's erratic and clumsy foreign policy actions were a major factor in the formation of the Triple Entente in the Treaty of St. Petersburg (August 31, 1907), even though this Entente, which anticipated the wartime coalition, was primarily concerned with settling colonial rivalries. Britain was not a permanent part of the alliance, however, and each side was careful not to be instrumentalized by the other. Thus, Russia kept its distance in the Morocco question, and in the Bosnian annexation crisis, neither France nor Britain wanted to intervene in Russia's favor. The second Morocco crisis was accompanied by a fierce antagonism between the German and French publics and induced France to reestablish relations with Russia that had cooled with the Bosnian annexation crisis, with France accepting the aggressive Balkan alliance supported by Russia despite misgivings. Germany's isolation, evident at the latest with the Algeciras Conference, led to unconditional alliance loyalty to Austria-Hungary, the last remaining ally.

Balance of power

On the eve of the war, the Central Powers were clearly inferior in terms of numbers, economic performance and armaments expenditure: in 1914, they (including Turkey) had a population of 138 million and 33 million men fit for military service, whereas the Entente (including colonies) had 708 million inhabitants and 179 million men fit for military service. The absolute armament expenditures of the Entente in 1913 were about twice as high as those of the Central Powers. Germany was superior only in terms of modern heavy artillery, which gave it a considerable advantage, especially in trench warfare, which was generally not expected. Infantry armament was balanced in terms of firepower, but British troops had an above-average infantry rifle. On the sea, the Entente and especially Great Britain were far superior to their opponents, so that a distance blockade of Germany could occur. Russia, however, could be cut off from supplies via the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea in return. Germany and Austria-Hungary had the geostrategic advantage of the Inner Line, which meant that the numerical superiority of the Entente did not initially come into play.

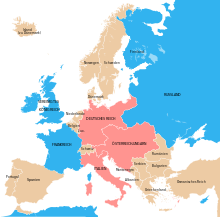

The official alliance system in 1914: Triple Alliance Triple Entente

The actual war constellation in the pre-war borders

.svg.png)

The European Alliance System around 1900 and 1910

Colonial empires in 1914

.jpg)

Language map of Austria-Hungary 1880

July crisis and the beginning of the war

→ Main article: July Crisis and Chronology of the July Crisis 1914

In the age of high imperialism, a considerable potential for conflict had accumulated in Europe. Nevertheless, the Sarajevo assassination (June 28, 1914) was not initially considered a threat to peace. In Vienna, only Chief of General Staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf and Finance Minister Leon Biliński - supported, however, by large sections of the press - advocated immediate mobilization against Serbia. In a conversation with Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold on July 1, von Hötzendorf made the war conditional on the question of whether Germany would "cover our backs against Russia or not." The German Foreign Office initially wanted to avoid war between Austria and Serbia, correctly foreseeing "world war" as a consequence. Until July 4, the Foreign Office was still of the opinion that Austria should not make humiliating demands on Serbia. As far as is known, a statement by Kaiser Wilhelm II ("The Serbs must be cleared up, and soon.") on July 4 led the Foreign Office immediately to take the opposite position.

| State | Alliance | War entry |

| Austria-Hungary | Central Powers | 49140728♠28 July 1914 |

| Serbia | Entente | 49140728♠28 July 1914 |

| German Empire | Central Powers | 49140801♠01 August 1914 |

| Russian Empire | Entente | 49140801♠01 August 1914 |

| Luxembourg | Entente | 49140802♠02 August 1914 |

| France | Entente | 49140803♠03 August 1914 |

| Belgium | Entente | 49140804♠04 August 1914 |

| Great Britain | Entente | 49140804♠04 August 1914 |

| Australia | Entente | 49140804♠04 August 1914 |

| Canada | Entente | 49140804♠04 August 1914 |

| Nepal | Entente | 49140804♠04 August 1914 |

| Newfoundland | Entente | 49140804♠04 August 1914 |

| New Zealand | Entente | 49140804♠04 August 1914 |

| Montenegro | Entente | 49140809♠09 August 1914 |

| Japan | Entente | 49140823♠23 August 1914 |

| South African Union | Entente | 49140908♠08 September 1914 |

| Ottoman Empire | Central Powers | 49141029♠29 October 1914 |

| Italy | Entente | 49150525♠25 May 1915 |

| San Marino | Entente | 49150601♠01 June 1915 |

| Bulgaria | Central Powers | 49151011♠11 October 1915 |

| Portugal | Entente | 49160309♠09 March 1916 |

| Hedjas | Entente | 49160605♠05 June 1916 |

| Romania | Entente | 49160831♠31 August 1916 |

| Greece | Entente | 49161124♠24 November 1916 /29 |

| United States | Entente | 49170406♠April 06, 1917 |

| Cuba | Entente | 49170407♠07 April 1917 |

| Guatemala | Entente | 49170422♠22 April 1917 |

| Siam | Entente | 49170722♠July 22, 1917 |

| Liberia | Entente | 49170804♠04 August 1917 |

| China | Entente | 49170814♠August 14, 1917 |

| Brazil | Entente | 49171026♠26 October 1917 |

| Panama | Entente | 49171110♠10 November 1917 |

| Nicaragua | Entente | 49180506♠06 May 1918 |

| Costa Rica | Entente | 49180524♠May 24, 1918 |

| Haiti | Entente | 49180715♠July 15, 1918 |

| Honduras | Entente | 49180719♠19 July 1918 |

Accordingly, on July 5, the legation councilor in the Imperial and Royal Foreign Ministry sent to Berlin, Alexander Hoyos (Mission Hoyos), was promised support. Foreign Ministry Alexander Hoyos (Mission Hoyos) pledged support for the course of the war and generally recommended an early strike. The following day, the Imperial Chancellor handed over to Envoy Hoyos and Ambassador Szögyény the official, identical reply, which was later interpreted as a blank check issued in "extreme negligence."

According to Kurt Riezler's diary entries from the meetings with Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg (July 7-8, 1914), the Reich leadership's motives were based on the consideration that a war could be won in 1914 rather than later due to Russia's growing military and transport potential. If Austria was not supported, there was a danger that it would turn to the Entente. Although the danger of world war was seen, the German Reich leadership hoped for localization and saw the situation as favorable: "If the war comes from the East, so that we therefore fight for Austria-Hungary and not East [reach]-Hungary for us, we have a chance of winning it. If the war does not come, if the Czar does not want it, or if dismayed France advises peace, we still have a chance to break up the Entente over this action.

The day after Hoyo's return (July 7), the Austro-Hungarian Council of Ministers decided to issue an unacceptable ultimatum to Serbia and to take military action if it was expected to be rejected.

From July 20 to 23, French President Raymond Poincaré and Prime Minister René Viviani visited the Russian capital of St. Petersburg and assured their hosts of their full support. There was a consensus that Serbia bore no responsibility for the killings, that the demands on Belgrade (already known in principle) were illegitimate, and that the Entente would stand firm against the Central Powers.

The opening of the July crisis in the narrower sense was the ultimatum issued by the Imperial and Royal Foreign Minister Count Berchtold to Serbia on July 23, 1914. Foreign Minister Count Berchtold issued to Serbia on July 23, 1914, with a deadline of 48 hours.

Encouraged by the results of the talks during the French government visit, the Russian Council of Ministers decided on July 24 to support Serbia and, if necessary, to initiate mobilization.

The corresponding telegram arrived in Belgrade on July 25, in time for the Serbian response to the ultimatum. The extent to which it influenced the Serbian rejection of the core points of the ultimatum is not clear. The response to Vienna was partly concessive, partly evasive. However, the participation of Austrian officials in the prosecution of suspects was flatly rejected on the grounds that it violated the Serbian constitution. Foreign Minister Nikola Pašić personally delivered the response to the Austrian legation shortly before the deadline. Ambassador Giesl skimmed the text and left immediately with the entire legation staff.

Doubts were raised in the Entente states that Austria-Hungary was the driving force behind the events; they increasingly suspected the significantly stronger Germany.

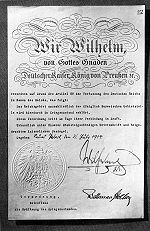

On the morning of July 28, 1914, Emperor Franz Joseph signed the declaration of war of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy to the Kingdom of Serbia (To My Peoples!) in Bad Ischl. Prior to this, the German government had again massively urged the ally to "discuss the matter immediately" since July 25. Vienna still wanted to issue the declaration of war only after the completion of mobilization and thus around August 12. Since the attack at Temes Kubin (alleged fire raid by the Serbs on July 26) was a propaganda fabrication and a pretended reason for war (similar to the Nuremberg airplane), the "shooting war" began shortly after 2 a.m. on July 29 with the shelling of Belgrade by the inland warships S.M.S Temes, Bodrog and Számos. Partial mobilization of the Russian army took place on July 29.

On July 29, Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg opened to British Ambassador Edward Goschen that Germany would attack France, breaking Belgian neutrality, and that in exchange for British neutrality, Germany offered to restore the territorial integrity of France and Belgium - but not that of their colonies - after the war.

Tsar Nicholas II approved the general mobilization of the Russian army on July 30, which was published the next morning (July 31). The German Empire then issued an ultimatum demanding the immediate withdrawal of the Russian mobilization (by 12 noon local St. Petersburg time on August 1), although it was known that it would be much slower than the German one. After the withdrawal failed to materialize, Wilhelm II issued the mobilization order on August 1 (5 p.m.) and declared war on Russia the same day (7 p.m. local St. Petersburg time). France, allied with Russia, also issued the mobilization order on August 1 (4 p.m.). On the morning of August 2, German troops occupied Luxembourg City as planned; mounted patrols entered France while war was still undeclared, killing one French and one German soldier. In the evening (8 p.m.) Belgium was requested to make a declaration within twelve hours to the effect that the Belgian army would be passive in the face of a passage of German troops; this was refused the next morning. On the evening of August 3, Germany declared war on France for alleged border violations and invented air raids ("Nuremberg plane"). On the same day, Italian Foreign Minister Antonio di San Giuliano informed German Ambassador Hans von Flotow that, in the Italian government's view, the casus foederis did not exist, since Austria and Germany were the aggressors. Already in the afternoon the Italian declaration of neutrality was made.

Also on August 3, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg sent a letter of justification to the British government. In it, Bethmann Hollweg described the "violation of Belgium's neutrality" as the consequence of a military predicament caused by the Russian mobilization. German patrols had already crossed the Belgian border that morning; corresponding reports were available in London. The German Empire thus violated Article I of the Treaty of London of April 19, 1839, in which the major European powers had guaranteed Belgian neutrality, and endangered British security interests. In the House of Commons on the afternoon of August 3, Edward Grey described the violation of Belgian neutrality and the danger of France's defeat as incompatible with British national interests, and Parliament followed this assessment.

At 6:00 a.m. on August 4, the German ambassador in Brussels informed the Belgian government that, having rejected his proposals, the German Reich felt compelled to use force, if necessary, to enforce the measures necessary to "repel the French threat." A few hours later, German troops marched into neutral Belgium in violation of international law and without a declaration of war. That same day (August 4), British Ambassador Goschen presented German Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg with a midnight ultimatum demanding a pledge that Germany would respect Belgian neutrality in accordance with the 1839 Treaty of London. Bethmann Hollweg reproached the ambassador for Britain going to war against Germany over a "scrap of paper," which was met with indignation in London. After the expiration of the ultimatum, Great Britain was in a state of war with the empire, and its dominions followed immediately (mostly without a separate declaration of war), so that within a few days the local war had developed into a continental war and from this into the world war. Austria-Hungary declared war on Russia on August 6, thus ending the "grotesque situation in which Germany found herself at war with Russia six days earlier than the ally for whose sake she had taken up the struggle in the first place.

·

Berlin, Unter den Linden: Announcement of the state of imminent danger of war on the afternoon of July 31, 1914 by an officer of the Alexander Guard Grenadier Regiment.

·

Berlin population with extra, August 1914

Wilhelm II decreed a state of war (announced as a state of imminent danger of war) on July 31, 1914, in accordance with Art. 68 of the Reich Constitution

Course of the First World War

History

See also: Chronology of the First World War

War year 1914

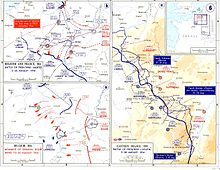

Failure of war plans and transition to positional warfare on the Western Front

While the assembly of the German army on the western border was still in progress, the German X. Army Corps carried out a hand-strike raid on the citadel of the Belgian fortress of Liège, already planned in the Schlieffen Plan. The city quickly fell into the hands of the attackers (August 5-7), while the belt of twelve forts could not be captured at first. Only after bringing in the heaviest artillery (Krupp's Dicke Bertha and Škoda's lesser-known, more mobile Schlank Emma) was it possible to occupy the forts and completely take Liège by August 16. The climax of the fighting is considered to be the destruction of Fort Loncin on August 15 by a direct hit in the ammunition room. The rapid elimination of the forts, which were considered impregnable, led to strategic changes in further French war planning.

On August 4, the first violent attacks on civilians occurred in the Belgian villages of Visé, Berneau, and Battice near Liège. In the coming weeks, German troops committed multiple atrocities against the civilian population in Belgium and France, justifying them as attacks by franc-tireurs. The first mass shootings of Belgian civilians took place on August 5, and German troops committed particularly serious war crimes in Dinant, Tamines, Andenne, and Aarschot. Between August and October 1914, about 6,500 civilians fell victim to reprisals, and the firebombings in Louvain received particular worldwide attention and condemnation. The reception of actual and invented assaults went into the English propaganda term Rape of Belgium, still in use today.

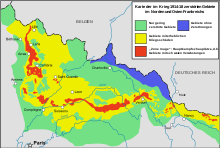

While the German troops unfolded their bow movement over Belgium within the framework of the Schlieffen Plan, Plan XVII was prepared on the French side, which, in contrast to the German encirclement strategy, relied on the strategy of penetration in the center (Lorraine). Before the actual large-scale attack under this strategy, an advance attack was made on Mulhouse/Mulhouse. In this way, French commander Joffre aimed to tie up German troops in the south and boost the enthusiasm of the French population by advancing into Alsace, which had fallen to Germany after the defeat of 1871, and he certainly succeeded during the short-term capture of the second largest city and the most important industrial center in the region. Mulhouse was taken on August 7, with part of the population there cheering the French soldiers. As early as August 9, the German troops were back in action. After another conquest, the city and all Alsatian territories, with the exception of the Doller valley and some of the Vosges heights, fell again to the Germans on August 24 for the rest of the war. General Louis Bonneau, who commanded the French attack, was dismissed by Joffre.

Joffre initially had no intention of being influenced by the German attack on Belgium in his deployment under Plan XVII and concentrated 1.7 million French troops in five armies for the attack. However, he could not completely ignore the movement of German troops and moved the 5th Army under Charles Lanrezac accordingly farther northwest. The British Expeditionary Corps under General John French, which had just landed in France, joined north at Maubeuge. The French offensive initially began on August 14, with the 1st Army under General Auguste Dubail and the 2nd Army under General Noël de Castelnau crossing the border and advancing on Saarburg (Lorraine) and elsewhere. The German 6th and 7th Armies - both commanded at the time by Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria - initially fell back fighting.

On August 18, after the defeat of the Liège fortress (final fall of Liège on August 16), the real major offensive of the German right wing to surround the Allied armies began. In the process, it advanced very quickly to Brussels and Namur. The main part of the Belgian army retreated to the fortress of Antwerp, whereupon the two-month siege of Antwerp began. On August 20, the French offensive proper began in the direction of German Lorraine and the Saar-Ruhr area, and at the same time the German counterattack began. From this and from a series of further battles near Saarburg, near Longwy, in the Ardennes, on the Meuse, between the Sambre and the Meuse and near Mons, battles between the Vosges and the Scheldt developed with heavy losses for both sides, the so-called border battles. The French troops suffered exceptionally heavy losses; between August 20 and 23, 40,000 soldiers fell, 27,000 on August 22 alone. The losses were caused mainly by machine guns. The French 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Armies were severely beaten head-on by the German 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th Armies, as were the 5th Army and the British Expeditionary Corps on the left wing. The French troops, however, succeeded in a sufficiently orderly retreat behind the Meurthe and the ring of fortifications around Nancy, on the one hand, and behind the Meuse, on the other, while preserving the fortress of Verdun, without the German troops succeeding in encircling and completely destroying large detachments. Disregarding the Schlieffen plan, Crown Prince Rupprecht asked Chief of Staff General Moltke to take advantage of the success and go on the offensive himself, which the latter approved. However, this German offensive between August 25 and September 7 brought no breakthrough.

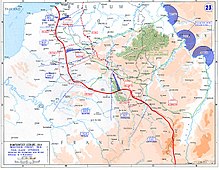

The French and British armies on the left wing began a general but orderly retreat through northern France, punctuated by isolated battles such as the Battle of Le Cateau (26 August) and the Battle of St. Quentin (29 August), bringing the pursuing German right wing ever closer to Paris. The French government left the capital on September 2 and moved to Bordeaux, and the defense of Paris was entrusted to the reactivated General Joseph Gallieni. The French high command, meanwhile, drew together troops from the right wing as well as reserves to raise a new (6th) army under Joseph Maunoury near Paris to threaten the German advance on the flank. Another (9th) army under Ferdinand Foch was inserted in the center. Joffre planned to use the Marne as a fallback position from which to halt the German advance with an offensive along the entire front.

The German swing wing-the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th German Armies-had already made its turn toward the southwest and south at still high speed; the 1st Army deviated southward from its planned direction of advance as early as after the capture of Brussels (August 20), as commander Alexander von Kluck pursued French troops and the British Expeditionary Corps. As the front expanded, the surprise effect of the German offensive diminished, and the numerical superiority of the German right wing was lost as it stretched; the German lines of communication became longer and longer, those of the French shorter and shorter. The dispersed German front threatened to break up by the end of August, the right wing was forced to change its line of thrust further and swing south and southeast due to counterattacks, and the encirclement of Paris was abandoned on August 30, of which Joffre was informed on September 3.

In the meantime, the Supreme Army Command stationed in Luxembourg lost track of the operational situation; above all, it lacked any telephone communication with the threatened right wing. The technically inadequate radio communications could not make up for this, and the airborne messages often went unused. The 1st Army (320,000 troops) attempted to encircle the British Expeditionary Force with forced marches, neglecting western flank protection. The surrender of two corps to the Eastern Front, siege troops left behind (Antwerp, Maubeuge), march and combat losses, and supply difficulties caused stalemates; the exhausted 1st Army had covered over 500 kilometers in heavy fighting.

On September 6, the French offensive against the open flank of the German army ("Battle of the Marne") began. The German 1st Army, which despite instructions to the contrary had still advanced south of the Marne on September 5, 1914, reaching as its westernmost points the communes of Le Plessis-Belleville, Mortefontaine and Meaux around Paris (furthest advance: ![]() 48,9732,905), was forced to retreat in a two-day forced march. By its sudden about-face, it caused a gap some 40 kilometers wide between the German 1st and 2nd Armies, into which strong French and British forces crashed about noon on September 8, 1914. The cohesion of the German front was torn, the danger of an operational breakthrough and an encirclement of the German armies grew hour by hour, there was a threat of strangulation and destruction of individual German army units, a hasty retreat, and at worst a rearward encirclement of the entire German Western Army. The German armies were at the end of their tether after their non-stop advance. Lieutenant Colonel Richard Hentsch, sent by the Oberster Heeresleitung (OHL) to the supreme command of the 1st and 2nd Armies, recommended withdrawal, which was ordered by the commanders-in-chief of the two armies on September 9, without further contact with neighboring armies or the OHL.

48,9732,905), was forced to retreat in a two-day forced march. By its sudden about-face, it caused a gap some 40 kilometers wide between the German 1st and 2nd Armies, into which strong French and British forces crashed about noon on September 8, 1914. The cohesion of the German front was torn, the danger of an operational breakthrough and an encirclement of the German armies grew hour by hour, there was a threat of strangulation and destruction of individual German army units, a hasty retreat, and at worst a rearward encirclement of the entire German Western Army. The German armies were at the end of their tether after their non-stop advance. Lieutenant Colonel Richard Hentsch, sent by the Oberster Heeresleitung (OHL) to the supreme command of the 1st and 2nd Armies, recommended withdrawal, which was ordered by the commanders-in-chief of the two armies on September 9, without further contact with neighboring armies or the OHL.

The necessity of the retreat - especially that of the 1st Army - was later disputed, but most people today hold the opinion formulated by Holger Afflerbach, for example: "Operationally, the order to retreat was correct and absolutely necessary, but its psychological effects were fatal. The Schlieffen Plan had failed, the constriction of the French army on the eastern border (Lorraine and Alsace) had failed. On September 9, Chief of Staff General Moltke saw the envelope; he wrote that day:

"Things are going badly ... The beginning of the war, which began so hopefully, will turn into the opposite [...] how different it was when we opened the campaign so gloriously a few weeks ago [...] I fear that our people in their frenzy of victory will hardly be able to bear the misfortune."

Chief of Staff General Moltke suffered a nervous breakdown and was replaced by Erich von Falkenhayn. The 1st and 2nd German Armies were forced to abandon the battle and withdraw, with the remaining assault armies following. The subsequent retreat of the German attack wing behind the Aisne resulted in the First Battle of the Aisne, which initiated the transition to positional warfare. However, the German forces were able to dig in after their retreat along the Aisne and re-establish a cohesive, resilient front. On September 17, the French counterattack came to a halt. In France, this German retreat was later dubbed the "Miracle on the Marne"; in Germany, the order drew the harshest criticism. Falkenhayn urged Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg to inform the German public about the critical military situation after the failure of the attack plan, but the latter refused.

At first, Falkenhayn stuck to the previous concept, according to which the decision should first be sought in the west. In the race to the sea (September 13 to October 19, 1914), both sides tried to outflank each other, and the fronts were extended from the Aisne to Nieuwpoort on the North Sea. In northern France, the opponents tried to resume the war of movement in the first weeks of October 1914, with the German troops achieving some successes with heavy losses (capture of Lille, Ghent, Bruges and Ostend), but without achieving a breakthrough. Thereafter, the focus of the fighting shifted further north to Flanders, and the English supply via Dunkirk and Calais was to be interrupted.

On October 16, 1914, the Declaration of the University Teachers of the German Reich was published. It was signed by over 3,000 German university professors, almost the entire faculty of Germany's 53 universities and technical colleges, and justified World War I as a "defensive struggle of German culture." Foreign scholars responded a few days later in the New York Times and The Times.

Fierce fighting developed at Ypres (First Battle of Flanders from October 20 to November 18, 1914). Hastily formed German reserve corps suffered devastating losses at Langemarck and Ypres. Inadequately trained young soldiers led by reserve officers with no front-line experience - occasionally 15-year-olds - went to their deaths here by the tens of thousands without achieving any significant objective. Nevertheless, the myth of Langemarck was constructed from this - the first significant example in this war of reinterpreting military defeats or failures into moral victories. In the process, the Allies succeeded in removing the Channel ports of Boulogne and Calais, important for British supplies, and the rail junction of Amiens from German grasp.

The war of movement ended with the fighting at Ypres. An extensive system of trenches (trench warfare) emerged on the German western front. All attempts by both sides to break through failed in 1914, and a front more than 700 kilometers long from the North Sea to the Swiss border (→ Switzerland in the First World War) froze in positional warfare; at the front sections, the frontmost trenches were often barely 50 meters from the enemy positions.

On November 18, 1914, Falkenhayn opened Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg that the war against the Triple Entente could no longer be won. He pleaded for a diplomatic liquidation of the war on the continent, for a negotiated and separate peace with one or more adversaries, but not with Great Britain, with which he did not consider a political settlement possible. Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg rejected this. The Reich Chancellor's reasons for this were primarily domestic; in view of the great sacrifices of the attack, he did not want to forego annexations and a "victory prize" for the people. Hindenburg and Ludendorff assumed that the enemy had an unconditional will to annihilate them and also still considered a victorious peace possible. The Reich Chancellor and the General Staff concealed from the nation the significance of the defeats on the Marne and at Ypres. In this way, they kept the nation's will to fight and persevere high. The discrepancy between the political-military situation and the war aims of the economic and political elites thus widened increasingly as the war progressed, contributing to the social front during the war and beyond.

In November 1914, the British navy declared the entire North Sea a war zone and imposed a distance blockade. Ships flying the flag of neutral states could become the target of British attacks in the North Sea without warning. This action by the British government violated applicable international law, including the 1856 Declaration of Paris, to which Great Britain was a signatory.

On December 24 and the following two days, the so-called Christmas truce, an unauthorized ceasefire among soldiers, took place on some sections of the Western Front. This Christmas truce, combined with fraternization gestures, probably involved over 100,000 mainly German and British soldiers.

Fighting in the East and the Balkans

→ Main articles: East Prussian Operation (1914), Battle of Galicia and Serbian Campaign 1914.

Since, contrary to the assumptions of the Schlieffen Plan, two Russian armies entered East Prussia two weeks after the outbreak of war and thus unexpectedly early, the situation on the eastern front was initially extremely tense for the German Reich. As a result of the Schlieffen Plan, the Germans were rather defensive on their eastern front; only a few Russian-Polish border towns had been occupied, with the destruction of Kalisz. After the Battle of Gumbinnen (August 19-20), the 8th Army defending East Prussia was forced to surrender large parts of the country. As a result, troops were reinforced and the previous commanders were replaced by Major General Erich Ludendorff and Colonel General Paul von Hindenburg, who initiated the securing of East Prussia with victory at the Battle of Tannenberg from August 26-31. In the process, German troops succeeded in encircling and largely destroying the Russian 2nd Army (Narew Army) under General Alexander Samsonov. The Battle of the Masurian Lakes followed from September 6 to 15, ending with the defeat of the Russian 1st Army (Nyemen Army) under General Paul von Rennenkampff. The Russian troops then evacuated most of East Prussia.

Russian troops occupied Galicia, which belonged to Austria-Hungary, after the Battle of Galicia from August 24 to September 11. The Austro-Hungarian army had to retreat to the Carpathians in September after an advance on the Galician capital of Lviv due to overwhelming Russian superiority (Battle of Lviv 26 August to 1 September). The first siege of Przemyśl from September 24 to October 11 was repulsed. A military operation organized to relieve the k. u. k. troops by the newly formed German 9th Army launched offensive in southern Poland (from September 29 to October 31) with the aim of reaching the Vistula failed. On November 1, Colonel General von Hindenburg was appointed Commander-in-Chief East of the German Army. On November 9, the second siege of Przemyśl began, which ended fatally for Austria on March 22, 1915, and on November 11, the German counteroffensive in the Łódź area, which lasted until December 5, after which the tsarist troops switched to the defensive. From December 5 to 17, Austro-Hungarian troops succeeded in halting a Russian advance on Kraków, after which the enemy initially remained in positional warfare in wide areas of the front. In the Winter Battle of the Carpathians (December 1914 to April 1915), the Central Powers were able to hold their own against Russia.

The starting point of the war, the conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, was marginalized in view of the large-scale escalation from August onward. The three offensives of the Austro-Hungarian army between August and December 1914 mostly failed or brought only partial successes; in December, Belgrade could be taken only briefly. The k. u. k. Army suffered a devastating failure in this theater of war as well. Especially the first imperial and royal offensives were accompanied by heavy attacks against the Serbian civilian population. Several thousand civilians were killed, villages plundered and burned. The Austrian army leadership partially admitted the assaults and spoke of "unorganized requisitions" and "senseless reprisals." The Serbian army was at the end of its tether after the show of force - against an opponent several times superior in resources - in December. In addition, epidemics had broken out in the country.

Entry of the Ottoman Empire into the war

German military missions to the Ottoman Empire and the construction of the Baghdad Railway had already intensified relations between the German and Ottoman Empires before the war. On August 1, there was the snubbing seizure of two battleships ordered in Britain, some of which had already been paid for. The government of the Ottoman Empire initially tried to stay out of the fighting in an "armed neutrality." The ruling Young Turks realized that they would have to lean on a major power in order to hold their own militarily. At Enver Pasha's instigation, a wartime alliance was finally formed with Germany and Austria-Hungary, which was controversial in the cabinet.

On September 27, the Dardanelles were officially closed to international shipping. After the two ships of the German Mediterranean Division under Rear Admiral Wilhelm Souchon, Goeben and Breslau, escaped the British Mediterranean Fleet and entered Constantinople, the two warships handed over to the Ottoman Fleet, still commanded by Souchon and manned by German sailors, fired on Russian coastal towns in the Black Sea on October 29. As a result, France, Britain, and Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire in early November. On the morning of November 14, the Sheikhül Islam of the Ottoman Empire Ürgüplü Mustafa Hayri Efendi proclaimed jihad against enemy states in front of the Fatih Mosque in Constantinople, following an edict by Sultan Mehmed V. During the war, this call resonated only with individual Muslim units in British service, such as Indian Muslims from Punjab who mutinied in Singapore on February 15, 1915. The call had a reinforcing effect on anti-British sentiment in Afghanistan, which erupted after the end of the war in the Third Anglo-Afghan War.

Shortly after the declaration of war, ready British-Indian troops landed at Fao in the Persian Gulf on November 6 to protect the British oil concessions of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, thus opening the Mesopotamian front. After several encounters with weaker Ottoman forces, they succeeded in capturing Basra as early as November 23.

Russian troops also opened the offensive on the Caucasus front in early November (Bergmann Offensive). There, an attempt to counterattack the Ottoman 3rd Army in winter resulted in its first heavy defeat at the Battle of Sarıkamış. On the Russian side, Armenian volunteer battalions took part in the fighting, which intensified sentiment against the Armenians among the Young Turk leadership, even though the majority of the ethnic group was loyal to the Ottoman Empire. Russian troops attacked from northeastern Persia, which they had occupied for some time (→ World War I in Persia). For the time being, there was no major fighting on the Palestine front.

War in the colonies

As early as August 5, 1914, the London Committee of Imperial Defence had decided to extend the war by unilaterally interpreting the treaties of the Berlin Africa Conference of 1884/85 ("Congo Conference") and to attack all German colonies or have them attacked by French, Indian, South African, Australian, New Zealand or Japanese troops. This resulted in some heavy fighting, especially in Africa. The colony of Togo, surrounded on all sides, was immediately taken. Cameroon was also difficult to hold: By the end of 1914, German troops had retreated into the hinterland. There, a grueling small-scale war developed that dragged on until 1916. The South African Union attacked German Southwest Africa, which initially held its ground at the Battle of Sandfontein from September 24 to 26. Delaying the South African Union attacks was the anti-British uprising by part of the Burian population, which was not finally put down until February 1915. German East Africa defended itself doggedly under Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck and initially forced the British troops to retreat at the Battle of Tanga (November 2-4, 1914). Thanks to the German strategy of retreats and guerrilla tactics, the Schutztruppe für Deutsch-Ostafrika was able to hold out until the end of the war. The German colonies in the Pacific, where no Schutztruppen were stationed, were handed over to Japan, Australia and New Zealand almost without a fight. The German colony of Kiautschou was fiercely defended during the siege of Tsingtau until material and ammunition were exhausted (surrender November 7, 1914).

See also: World War I outside Europe

War year 1915

Submarine warfare

On February 4, the German Reich made the official announcement of submarine warfare against merchant ships on February 18. The waters around Great Britain and Ireland were declared a war zone against the protest of neutral states, although there were not enough submarines available to effectively blockade Great Britain. By using U-boats against merchant ships, Germany broke new ground both militarily and under international law. U-boats could only imperfectly comply with the rules of the Prisenrecht, especially since the increasing armament of British merchant ships endangered the safety of the boats. In addition, submarine commanders were not given clear instructions for execution. The naval leadership evidently assumed that most sinkings would be made without warning and that a deterrent would thereby be achieved vis-à-vis neutral shipping. However, due to protests from neutral countries following the German announcement, U-boat warfare was formally restricted in that no neutral ships were to be attacked.

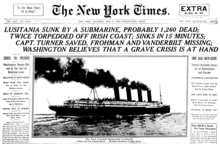

On May 7, the German submarine U 20 sank the British passenger ship Lusitania, which triggered a wave of protest, especially in the United States. This was because over 200 U.S. citizens were on board the Lusitania when it left the port of New York on May 1, 1915, even though the German embassy in Washington had issued advertisements warning against using British ships to cross to the United Kingdom. For Americans, the sinking of the Lusitania and the deaths of the many Americans came as a shock that made you realize how difficult it was to stay out of the world war. When the passenger liner was sunk on May 7, 1198 passengers and crew members died, including nearly 100 children and 127 U.S. citizens. There was outrage in America, and an exchange of notes between the American and German governments followed. On June 1 and 6, the Kaiser agreed to the Reich Chancellor's request (at the time still supported by the OHL on this issue) that German submarines should not sink neutral ships and, in general, large passenger steamers. Grand Admiral Tirpitz and Admiral Gustav Bachmann immediately submitted resignation petitions for this reason, which the Kaiser rejected in curt terms. After the sinking of the steamer Arabic on August 19, 1915, by U 24, in which Americans were again killed, Ambassador Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff made clear the restrictions now imposed by the American government (Arabic pledge). The German press was informed at the end of August and its chief editors - explicitly Ernst Graf zu Reventlow, but also Georg Bernhard - were instructed by the General Staff to immediately cease the campaigns conducted by some newspapers for unlimited submarine warfare and against the U.S. (based on their notes).

Germany seeks war decision on the Eastern Front

On the Eastern Front, the German army, with the help of the newly arrived 10th Army, defeated the Russians in the Winter Battle of Masuria from February 2 to 27. The Russian troops then withdrew from East Prussia for good.

In November 1914, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich von Ludendorff, as his Chief of Staff, had been given supreme command of all German forces on the Eastern Front and since then had successfully worked to try to win the war in the East in 1915. The goal of the German leadership was to prepare to blow up the opposing coalition by weakening Russia. Since the general situation in the east - almost all of Galicia was Russian-occupied - made a separate peace move on the part of the Central Powers seem unpromising for the time being, military means were to be used to increase pressure on Russia and also to make a favorable impression on the neutral states, especially in the Balkans. Above all, the expected entry of Italy into the war threatened a dangerous strategic situation for Austria-Hungary: the Russians had been able to hold their own in the Carpathian Mountains during the Winter Battle, but if Italy had entered the war, a large-scale pincer movement (between the Isonzo and the Carpathians) could have meant the military end of the Danube monarchy. A breakthrough in western Galicia up to the San was to force the Russian formations to retreat from the mountains, otherwise they would have to fear encirclement on their part. For this purpose, parts of the Western Army (the 11th Army under August von Mackensen) were transferred to the Eastern Front in the spring of 1915. From May 1 to 10, the Battle of Gorlice-Tarnów took place east of Kraków, in the course of which the German and Austro-Hungarian troops (4th Army) succeeded in making an unexpectedly deep penetration of the Russian positions, reaching the San by mid-May. The battle marked a turning point on the Eastern Front. The success could not hide the fact that Austria-Hungary had to bear losses of nearly 2 million men from the beginning of the war until March 1915 and was increasingly dependent on massive German aid.

In late June, the Central Powers continued their attack with the Bug Offensive. After the recapture of Przemyśl on June 4 and Lemberg on June 22, the strangulation of the front arc in Russian Poland seemed within reach; with coordinated attacks from the north and south, the Russian formations were to be encircled there, and the Supreme Army Command - with such success in mind - postponed attacks on other fronts. However, this planning by Ludendorff seemed too ambitious to Falkenhayn and Mackensen - in view of the experience in the Battle of Marne - and was scaled down accordingly. The Bug Offensive (June 29-September 30) and the Narew Offensive (July 13-August 24) did not result in the encirclement of large bodies of troops, but the Russian army was forced into a "Great Retreat." Evacuation of Poland, Lithuania, and large parts of Courland and shortening of the Russian front from 1600 to 1000 kilometers. By September, the Central Powers succeeded in capturing important cities such as Warsaw (August 4), Brest-Litovsk and Vilnius. In Russian Poland, the occupying powers created two general governorates: an Austrian one in Lublin and a German one based in Warsaw. In "Upper East," de facto a military state in the territories under German supreme command other than Russian Poland, an occupation policy was subsequently pursued for the intensive economic exploitation of the country and its human resources. Toward the end of September, further offensives by the 10th Army under Ludendorff against Minsk and by Austrian troops against Rovno failed. Despite the Russian army's higher overall losses, it continued to outnumber the Germans after the conclusion of the Great Retreat (September 1915), and the planned redeployment of large parts of the German forces to the Western Front could not take place to the extent hoped for.

The Western Front 1915

On the Western Front, the Allies initially pursued the classic strategy of cutting off the great German frontal arc between Lille in the north and Verdun in the south by pressing both flanks and, if possible, interrupting the rail lines that were important for supplies. This strategy initially led to the Winter Battle in Champagne (until the end of March), which had already been prepared at the end of 1914 and in which the type of material battle emerged: days of artillery fire escalating to a barrage intended to massively demoralize and wear out the enemy, followed by the massive infantry assault. However, this tactic did not succeed, as the Germans were prepared for the attack by the shelling and were able to repel it with barrage and machine gun fire due to structural advantages of the defender in trench warfare from the well-developed dugouts. Allied attacks on the small, strategically threatening frontal arc of Saint-Mihiel (Easter Battle or First Woëvre Battle between Meuse and Moselle) also failed.

The use of poison gas on the first day of the Second Battle of Flanders, April 22, is considered a "new chapter in the history of warfare" and the "birth of modern weapons of mass destruction." Although irritants had also been used by the Allies before in the gas warfare during World War I, since lethal chlorine gas was used on April 22, the attack was internationally considered a clear violation of the Hague Land Warfare Regulations and was exploited accordingly for propaganda purposes. The gas attack was carried out using Haber's blowing method, which depended on the wind direction. As early as March, sappers installed concealed gas cylinders in the front trenches near Ypres, from which the gas was to be blown off. Since easterly winds are relatively rare in West Flanders, the attack had to be postponed several times. On April 22, a steady north wind blew, and accordingly the gas was blown off the northern part of the Allied front arc around Ypres. The effect was much more serious than expected: The French 87th as well as the 45th (Algerian) Division fled in panic, opening a six-kilometer-wide gap in the Allied front. The death toll from this gas attack was contemporarily put at up to 5000; today's estimates are around 1200 dead and 3000 wounded. The German leadership had not expected such an effect and probably for that reason did not provide sufficient reserves for a further advance, apart from that the gas impaired the attackers. The frontal arc of Ypres was merely reduced in size during the Second Battle of Flanders and could be held by the British troops and the newly arrived Canadian division at the front. Due to the use of gas, casualties among the defenders were significantly higher than among the attackers (about 70,000 to 35,000), which was unusual for trench warfare in the First World War.

On May 9, the British and French attempted a breakthrough in Artois in the Battle of Loretto. Despite enormous losses (111,000 Allied and 75,000 German soldiers), this produced only partial successes and was broken off in mid-June. On the German side, tactical changes increasingly succeeded in further expanding the defender's structural advantages in trench warfare: While traditionally the defense had been concentrated on a first line in a forward slope position (best overview and wide field of fire), the German troops increasingly switched to shifting the focus of the defense to the second line in a rear slope position due to the Allies' material superiority. On the one hand, this gave the Allies enough time to bring up reserves during the breakthrough; on the other hand, the superior Allied artillery was no longer accurate enough to eliminate the German positions due to the lack of a direct line of sight.

The last major combat operations on the Western Front of the 1915 war year were Allied offensives between September 22 and October 14, again in Artois and Champagne. The Autumn Battle of Champagne and the Autumn Battle of La Bassée and Arras produced hardly any results, with heavy losses and successively increasing use of materiel: "The Entente troops had to pay for minimal gains in terrain with losses of up to a quarter of a million men."

The Gallipoli Operation of the Allies

→ Main article: Battle of Gallipoli

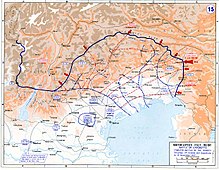

On February 19, the Allied Dardanelles Operation began with the shelling of Turkish coastal forts along the Dardanelles by British and French warships. Initially, minesweepers attempted to clear Turkish mine barriers in the strait in order to reach the objective of Constantinople directly. The Allies' intention was to push the Ottoman Empire out of the war by threatening its capital and to open the supply route to Russia through the Dardanelles. On March 18, a breakthrough attempt was made by naval forces under Admiral John de Robeck, sinking three Allied battleships and damaging others. As a result, the Allied governments decided to force the opening of the Dardanelles by landing ground troops. Previously, British military forces had considered troop landings at Alexandretta to separate the southern areas of the Ottoman Empire from the Anatolian heartland.

On April 25, the Allied landings began on the Gallipoli Peninsula and on the opposite Asian coast at Kum Kale. Allied troops had previously occupied the island of Limnos, among others, in defiance of Greek neutrality, in order to use it as a base for attacks against the Ottoman Empire. 200 merchant ships-covered by 11 warships-deployed 78,000 British troops of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and 17,000 French troops of the Corps expéditionnaire d'Orient, including the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) in its first wartime deployment. The attack failed due to unexpectedly fierce Turkish resistance, with Mustafa Kemal in particular standing out as commander of the 19th Division in the 5th Ottoman Army under the overall command of Otto Liman von Sanders, laying the foundation for his reputation as a popular hero. The operation, in which a total of over 500,000 Allied soldiers were engaged, had to be called off by January 9, 1916, with a full-scale amphibious evacuation. In the battle, 110,000 soldiers from both sides lost their lives.

Italy's entry into the war

On May 23, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary. Since January, Germany had been pressuring Austria to cede Trentino and other territories to Italy in order to at least guarantee its neutrality. Even after the denunciation of the Triple Alliance on May 4, more and more extensive offers were made to Italy, including on May 10 the cession of Trentino and the Isonzo region, a largely free hand in Albania, and more. On the other hand, Italy had negotiated with the Allies and, in the London Treaty of April 26, had obtained more far-reaching promises in the event of the Allies entering the war. Prime Minister Antonio Salandra and Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino had decided, after months of tactics, to declare war on Austria with the express approval of King Victor Emmanuel III. In doing so, they followed the pressure of public opinion, although there was no majority in favor of war among the population or in Parliament at the time of the declaration. The supporters of the war against Austria were far more active and were able to unite the most important Italian opinion leaders from all political directions. Political irredentism, for example, was able to draw on Cesare Battisti. Gabriele D'Annunzio - writer and later pioneer of European fascism - organized public events and mass demonstrations for the war in Rome, while the socialist publicist Benito Mussolini had been advocating the war since October 1914, which led to his expulsion from the Partito Socialista Italiano. Mussolini then founded his own newspaper, Il Popolo d'Italia, presumably financed by France, with which he continued to call for Italy to enter the war on the side of the Entente. The war supporters received further public support from the Futurists around Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Although the parliament supported the neutrality course of majority leader and previous prime minister Giovanni Giolitti shortly before the declaration of war, which earned him calls for assassination from D'Annunzio, the parliament was not the real locus of political decision-making. When it was convened on May 20 on the occasion of the approval of the war credits, only the Socialists voted against the credits, while the former opponents of the war, such as the Giolitti supporters and the Catholics, sought to prove their patriotic attitude by accepting the war credits.

The Italian front ran from the Stelvio Pass on the Swiss border through Tyrol along the Dolomites, the Carnic Alps and the Isonzo to the coast of the Adriatic Sea. As a result, Austria-Hungary was immediately in a three-front war, which complicated the situation for the Central Powers. In addition, the Austrians were not able to secure parts of the Italian front sufficiently at the beginning of the fighting; in many cases only local militias, Landwehr and Landsturm were used, including 30,000 Standschützen. The fighting on the Isonzo began immediately after the declaration of war, the actual start of the First Battle of the Isonzo being set for June 23. Despite great superiority and territorial gains, the Italians failed to make a decisive breakthrough either in this battle (until July 7) or in the Second Isonzo Battle that immediately followed (July 17-August 3). This was also true of the Third and Fourth Isonzo Battles; high losses in men and materiel were accompanied by no changes in the overall strategic picture. The First Dolomite Offensive (July 5-August 4), which marked the beginning of the Alpine War, also fit into this picture and constituted another novelty in military history: Never before had there been prolonged combat operations in the high mountains, which took place up to a sea level of 3900 meters (Ortlerstellung).

Armenian Genocide

Since the Battle of Sarıkamış, the Young Turk leadership increasingly suspected Armenians of sabotage. When the Russians approached Lake Van in mid-April, five local Armenian leaders were executed in this region. This and other incidents led to unrest in Van. On April 24, a wave of arrests of Armenian intellectuals began in Constantinople (now a national day of remembrance in Armenia). On May 24, Russian Foreign Minister Sasonov issued an international protest note (prepared as early as April 27) claiming that the population of more than 100 Armenian villages had been massacred, and that representatives of the Turkish government had coordinated the killings. The following day (May 25), Ottoman Interior Minister Talât Pasha announced that Armenians would be deported from the war zone to Syria and Mosul. On May 27 and on May 30, the government of the Ottoman Empire issued a deportation law, beginning the systematic phase of the Armenian genocide and the Assyrian genocide. German Ambassador Hans von Wangenheim reported to Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg as early as June of Talât Pasha's view that "the Porte wanted to use the world war to thoroughly clean up its internal enemies - the local Christians - without being disturbed by the diplomatic intervention of foreign countries." Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter, German vice-consul in Erzerum, also reported in late July "that the ultimate goal [of the] action against the Armenians was the complete extermination of them in Turkey." In December 1915, the German ambassador and Wangenheim's successor, Paul Metternich, tried to intervene with the Turkish government in favor of the Armenians and suggested that the German government make the deportations and outrages public. However, this was not approved by Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, who noted instead: "The proposed public coramation of a confederate during the ongoing war would be a measure unprecedented in history. Our only aim is to keep Turkey at our side until the end of the war, whether Armenians perish over it or not." Even an intervention by Pope Benedict XV, who wrote directly to Mohammed V, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, came too late. The genocide claimed an estimated one million lives by the end of the war and was contemporarily referred to as the "Holocaust" even in its precursors (the massacres and pogroms of 1895/96 and the massacre of Adana in 1909).

Bulgaria's entry into the war and the Central Powers' campaign in Serbia

The Central Powers were reinforced by Bulgaria's entry into the war on October 14, 1915. In the Balkan Wars, Bulgaria had not been able to assert its territorial claims for the creation of an "ethnic Bulgaria"; practically all conquests made in the First Balkan War had to be surrendered again in the Peace of Bucharest in 1913, and the country was also considerably weakened by the wars. Thus, on August 1, 1914, the government of Vasil Radoslavov initially declared Bulgaria's strict neutrality. The Central Powers and the Allies subsequently made efforts to persuade Bulgaria, which in turn could make its participation in the war dependent on the respective offer. In this respect, the Central Powers were in the better starting position; they could more easily accommodate territorial interests at the expense of Serbia and, if necessary, Romania and Greece (whose entry into the war was expected on the Allied side) than the Allies; thus, the Bulgarians were promised Macedonia, Dobruja and Eastern Thrace. Accordingly, and due to the relatively favorable course of the war in the fall of 1915, Bulgaria gave the go-ahead to the Central Powers. As early as September 6, Bulgaria had agreed to cooperate with the Central Powers, who wanted to establish a land link with the Ottoman Empire by attacking Serbia. Participation in the war was extremely controversial in Bulgaria; after the government's decision to enter the war, the opposition parties - with the exception of parts of the Social Democrats - went along with the war course. On October 6, under the command of Mackensen, the Central Powers began their offensive against Serbia, and on October 14 Bulgaria declared war on Serbia. Thus the Serbs faced a considerable superiority, which the Allies could not counterbalance with a landing of troops north of Thessaloniki. Greece refused to enter the war on the side of Serbia, citing insufficient Allied support, although it had pledged to support Serbia in a bilateral treaty on June 1, 1913. After the fall of Belgrade (October 9) and Niš (November 5), the remnants of the Serbian army (about 150,000 men; at the start of the war, 360,000 men) led by Radomir Putnik withdrew to the Albanian and Montenegrin mountains with about 20,000 prisoners of war; it later returned to action on the Saloniki front after being regrouped on Corfu. Occupied Serbia was divided between Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria.

Other secondary fronts in 1915

The Battle of Sarıkamış on the Caucasus Front ended in a heavy defeat for the Ottoman Empire on January 5, 1915. On the Palestine Front, Ottoman troops under Friedrich Freiherr Kreß von Kressenstein undertook an unsuccessful offensive against the Suez Canal starting in late January.

The surrender of the German Schutztruppe in July 1915 ended the fighting in southwest Africa.

At the end of November, the British advance on the Mesopotamian front (now Iraqi territory) was halted by the Ottoman army under the de facto command of Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz at the Battle of Ctesiphon (November 22-25), and the expeditionary corps of the British Indian Army was trapped in Kut on December 7 (→ Siege of Kut).

Political and social developments

Joseph Joffre, commander-in-chief of all French troops since early December, convened a conference of the Allies from December 6 to 8 in Chantilly, where the Grand Quartier Général had been based since October 1914. To deprive the Central Powers of the advantages of the "Inner Line," coordinated attacks on all fronts were arranged for mid-1916. The British government under Herbert Henry Asquith had to be reshuffled in May of that year to include the hitherto opposition Conservatives because of the unfavorable war situation, especially at the Dardanelles. The coalition government under Asquith included a Ministry of Munitions in response to the munitions crisis of the spring of 1915.

In October and November, in view of the tightened food restrictions, there were initially riots in front of grocery stores, distribution points and free benches in Germany, but increasingly also protest gatherings of very predominantly female demonstrators. On November 30, 58 women were arrested at a protest meeting on Unter den Linden in Berlin; the press was not allowed to report on it. Prices for grain, bread, butter and potatoes had already risen sharply in November 1914, and at this point farmers were reluctant to supply the city markets, if at all. The reasons for the supply problems lay in the organizational inability of the authorities - no one had expected and prepared for a long war - as well as in the loss of food and saltpeter imports (the latter for fertilizer production); in addition, the war deprived agriculture of horses and labor. The Federal Council set maximum prices for bread, potatoes and sugar at the end of 1914, followed by other staple foods in January 1915, so that farmers increasingly tried to market their goods in "surreptitious trade." At the end of 1915, one observer noted: "The inflation has taken on a threatening character [...] The change of mood in the last few weeks, since the beginning of the stricter food restrictions, is very strong. Especially the women are becoming rabid [...] the women are shouting 'give us food!' and 'we want our men'". With the black market flourishing, the population believed less and less the official propaganda that the English naval blockade alone was responsible for the poor food supply. The consequence of the state's inability to deal with the food question was a gradual "alienation of the citizens from the state, indeed an actual 'delegitimization' of the state," beginning at the end of 1915 at the latest.