Wood

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Wood (disambiguation).

Wood (from Germanic *holta(z), 'wood', 'copse'; from Indo-European *kl̩tˀo; original meanings derived from Indo-European *kel-, 'to beat': 'cut off', 'split', 'beatable wood') in common usage refers to the hard tissue of the shoot axes (trunk, branches and twigs) of trees and shrubs. Botanically, wood is defined as the secondary xylem of seed plants produced by the cambium. According to this definition, however, the woody tissues of palms and other higher plants are not wood in the strict sense. Characteristic of wood, however, is the incorporation of lignin into the cell wall. In a more extensive definition, wood is therefore also understood as lignified (woody) plant tissue.

In terms of cultural history, woody plants are probably among the oldest plants in use. As a versatile, but especially renewable raw material, wood is still one of the most important plant products as a raw material for further processing and also a regenerative energy source. Objects and structures made of wood (e.g. bows and shields, charcoal, pit timber, railway sleepers, wooden boats, pile dwellings, forts) as well as the timber industry were and are a part of human civilisation and cultural history.

The clearing of forests along the coasts of the Mediterranean was one of the first major human interventions in an ecosystem. Clearing was the first step towards making Europe, which was largely forested, arable.

One cubic metre of wood, Dosenbek, Schleswig-Holstein

Various wood species, from top to bottom: Weymouth pine, wenge, ramin, macassar ebony, maple burl, bog oak.

Origin of wood

Wood is formed by the cambium, the formation tissue between wood and bark (secondary thickness growth).

When a cambium cell divides, two cells are formed, one of which retains its ability to divide and grows into a new initial cell. The other becomes a permanent cell that divides once or several times. The cells that later differentiate into conductive, strengthening or storage tissue develop into wood on the inside (secondary xylem). To the outside, bast (phloem, pronounced phlo-em) is produced, which makes up the inner bark and later gives rise to the bark formed by the phellogen. The production of xylem cells exceeds the production of phloem cells many times over, so that the proportion of bark in the total stem is only about 5 to 15 percent.

In the northern temperate zone, there are four phases of growth due to the climate:

- Dormant period (November to February)

- Mobilisation phase (March, April)

- Growth phase (May to July): Wood cells that develop during this season are large-lumened, thin-walled and light-coloured and form the so-called early wood.

- Deposition phase (August to October): Wood cells that develop during this season are small-lumened, thick-walled and dark in colour and form the so-called late wood (or autumn wood).

This cyclical growth behaviour results in annual rings, which are clearly visible in a cross-section through a trunk (see also dendrochronology).

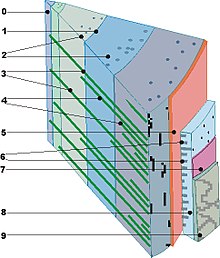

0 pith, 1 annual ring boundary, 2 resin canals, 3 primary wood rays, 4 secondary wood rays, 5 cambium, 6 wood rays of bast, 7 cork cambium, 8 bast, 9 bark

Structure

Wood has a species-specific anatomical structure, so that wood species can be distinguished from each other on the basis of their macro- and microstructures. The scientific description of wood structures and determination of wood species is the task of wood anatomy.

· Different wood structures

·

Spruce (Picea abies) in SEM

·

Oak wood (Quercus robur) with rows of pores (cross section)

·

Beech wood (Fagus sylvatica) with wood rays (tangential cut)

·

Wood of mulberry fig (Ficus sycomorus) with axial parenchyma (light microscope image)

Chemical components

| Composition of the cell wall in | ||

| Substance | Softwood | Hardwood |

| Cellulose | 42–49 % | 42–51 % |

| Hemicellulose | 24–30 % | 27–40 % |

| Lignin | 25–30 % | 18–24 % |

| Extractives | 2–9 % | 1–10 % |

| Minerals | 0,2–0,8 % | |

The lignified cell wall of hardwoods and conifers contains the framework substances cellulose, hemicelluloses and lignin as well as, to a lesser extent, so-called extractives. Cellulose and hemicellulose are often combined under the term holocellulose. Microfibrils are the essential structural element of the cell wall.

The proportions of lignin and hemicellulose are different for softwoods and hardwoods. The elemental mass fractions of dry wood are about 50 % carbon, 43 % oxygen, 6 % hydrogen and 1 % nitrogen and other elements.

Softwood

→ Main article: Softwood

Developmentally, conifers are older than hardwoods, therefore have a simpler anatomical cell structure than the latter and possess only two cell types.

- Tracheids: Elongated (prosenchymatic) cells tapering at the ends and filled only with air or water. They combine a conductive and strengthening function and account for 90 to 100 percent of the wood substance. The exchange of water between the cells takes place via so-called spots or court spots. In the wood rays they provide as cross tracheids for the water and nutrient transport in radial direction. They account for 4 to 12 percent of the total wood substance.

- Parenchyma cells: In longitudinal section, mostly rectangular cells that conduct nutrients and growth substances and store starch and fats. In radial direction they form the major part of the wood ray tissue as wood ray parenchyma. The parenchyma cells surrounding the resin ducts function as epithelial cells and produce the resin, which they secrete into the resin duct.

· Coniferous and deciduous wood

·

Spruce wood

·

Pine

·

Cherry wood

·

Rosewood

Hardwood

→ Main article: Hardwood

The developmentally younger hardwood tissue is much more differentiated than that of the softwood. It can be divided into three functional groups.

- Leading tissues: vessels (tracheids), vascular tracheids, vasicentric tracheids. The latter two are intermediate stages in the development from tracheid to vessel.

- Tendons: libriform fibres, fibrous tracheids

- storage tissue: wood ray parenchyma cells, longitudinal parenchyma cells, epithelial cells

Characteristic of hardwoods are the vessels not present in softwoods. They are often visible to the naked eye as small pores in the cross-section of the wood and as grooves in the tangential section. A distinction is made according to the arrangement of these tracheae:

- ring-porous woods (e.g. oak, sweet chestnut, ash, robinia, elm). These species form wide-lumen vessels in the early wood, but predominantly narrow-lumen tracheids and wood fibres in the late wood.

- semi-porous woods (e.g. walnut, cherry, decayed wood)

- scattered pore woods (e.g. birch, alder, lime, poplar, copper beech, willow). These species form vessels with approximately the same lumen throughout the growing season.

The growth zones (annual ring pattern) and the species-specific arrangement of pore and parenchyma strands result in the characteristic grain of the wood species.

Embedding

→ Main article: Heartwood

The term "kerning" of wood refers to the interruption of the trunk's internal water conduction pathways and the death of the cells. This occurs in conifers by closure of the pits and in many hardwoods by thylization of the cell lumens at an age of approx. 20-40 years. Thereafter, phenolic core ingredients are formed and incorporated into the cell walls, often leading to an increase in natural durability. If the heartwood area is clearly recognizable by a dark coloration, one speaks of heartwood trees (e.g. oak, pine, Douglas fir, larch, black locust). If no difference in color is discernible, but the reduced moisture content indicates that the inner area is pitted, we speak of mature trees (e.g. spruce, fir, lime, pear). Matured wood is genuine heartwood.

In contrast, numerous trees tend to have facultative kernel formation (e.g. ash, beech, cherry). Although the kernel is set off in colour, it is referred to as a false kernel, since kernel formation does not occur endogenously and regularly, but is triggered by exogenous influences (injuries). The false heartwood has no increased durability. Sapwood is the area of the trunk that actively participates in water and nutrient transport and storage.

Questions and Answers

Q: What are the main substances in wood?

A: The main substances in wood are cellulose and lignin.

Q: What are the uses of wood?

A: Wood is used for making buildings, furniture, art, as a fuel, and for producing paper.

Q: Is wood a renewable resource?

A: Yes, wood is a renewable resource, although it has become scarcer in recent centuries.

Q: When did wood originate?

A: Wood originated about 425 million years ago.

Q: What is a lumberjack?

A: A lumberjack is a person who cuts down trees.

Q: What is lumber, and what can it be used for?

A: Lumber is the long, straight pieces of wood that are cut from a tree. It can be used to make posts or wooden frames for other shapes with nails or screws.

Q: What are the different types of wood?

A: The commonly used types of wood are oak, maple, pine, and redwood. Wood is usually divided into softwood (from conifers) and hardwood (from flowering plants).

Search within the encyclopedia