Women's suffrage in the United States

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other historical topics related to women's suffrage in the United States, see Women's suffrage in the United States.

Women's suffrage in the United States - or rather the history of the women's suffrage movement in the United States - describes the lengthy process leading up to the legal admission of women to political elections. Women's suffrage was established over a period of more than half a century, first in individual states and localities and sometimes on a limited basis. In 1920, only after World War I, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution gave women the right to vote at the national level.

The demand for women's suffrage, which was not thought of in the 18th century when male independence was declared, became stronger in the 1840s. A broad movement for the assertion of women's rights developed. 1848 to 1860 saw the first gatherings of women's rights activists and the first "National Women's Rights Conventions", which led to a greater public awareness of these ideas. A group of well-known women leaders emerged, often fighting for other causes as well, such as opposing slavery or alcohol abuse.

This women's rights and women's suffrage movement was not able to develop into a true social movement until after the War of Secession. Two national organizations emerged in 1869, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) and National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which did not unite again until 1890, when they became the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Changing social conditions, the changing position of women in the economy and the public sphere, meant that at the turn of the 20th century (1890 to 1916) real opportunities arose for the legal realization of women's rights and women's suffrage.

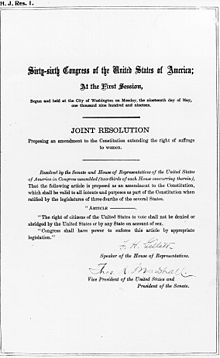

The "victory" was won between 1917 and 1920, after good tactical and strategic preparatory work by the two women's associations; in addition to the NAWSA, the more radical National Woman's Party (NWP), founded by Alice Paul, had existed since 1916. In many states they had already achieved women's suffrage and thus gained more and more influence on the elections to the House of Representatives and the Senate. First the House of Representatives, then the Senate passed the 19th Amendment. And after a painstaking ratification process, the necessary last state - Tennessee - also approved the Amendment to the Constitution by a narrow majority. 72 years after the Seneca Falls Convention, the goal was achieved: national suffrage for women in the United States:

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

(German: "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or restricted by the United States or by any State on account of sex.")

The 19th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America (Woman Suffrage) of 1920.

_(14778322302).jpg)

NAWSA Headquarters in New York .

.jpg)

Carrie Chapman Catt

Natural law and human rights as ideas of man

→ Main article: Natural law

In the formulation of human rights in the great debates leading up to the writing of the Declaration of Independence and the American Constitution, it was always assumed that the principles of natural law and the principle that the "consent of the governed is essential to just government" applied only to men. The theorists of liberal thought could never conceive of political or public participation by women. Like slaves and dependent servants, women simply did not exist in the realm of law.

While gradually all white men were given the right to vote, democratic logic was much slower to take hold with regard to women. The idea of men's equality went hand in hand with the idea of women's inferiority and different nature. Men had a profound idea of the "true nature of women" and probably feared nothing more than that the entrenched relations of the sexes might be changed.

In addition, there was the legal position of the married woman in the so-called conjugal guardianship, which was widespread in the Anglo-Saxon area and in the USA. As a wife, a woman could not exercise her rights in the same way as a man, but required male assistance or guardianship, i.e. the husband. She had to leave the management of her affairs entirely to her husband. A kind of patriarchy prevailed.

And a fundamental problem always arose for the rather lawless women in politics and public life: how to bring about or influence pro-women legislation if the elected representatives of the legislative body need not fear election by women, since only men are allowed to vote? This problem played a significant role throughout the 19th century.

Growth of a new idea: women's rights

→ Main article: Gender guardianship

For two hundred years, women in America had worked alongside men, listening to political discussions and watching the growth of local, state, and federal governments and their policies. And they had rarely complained publicly that they were not empowered to vote or hold office. It was not until the second and third decades of the 19th century that the question was raised here and there, and in the fourth decade that the idea emerged that women should have a change in their political status.

This was because women participated in party election campaigns and became increasingly important as supporters, it was because they were concerned with the moral regeneration of society and with humanitarian and philanthropic issues, and it was further because they wanted to advance educational opportunities for women and teacher training. There were also women among the workers in the early textile mills who confronted the problems of the new relationships with the masters of the mills and the working conditions that prevailed in the mills, and who spoke and wrote publicly about them.

The debate about the emancipation of slaves also changed women's attitudes about their role in society and made them aware of some limitations. For example, Angelina Emily Grimké wrote: "The investigation of the rights of the slaves has led me to a better understanding of my own." (German: Die Erforschung der Rechte der Sklaven hat mich zu einem besseren Verständnis meiner eigenen geführt. ) And she added that all human beings should have the same rights because all these rights arise as a product of the moral nature of the human being.

As the controversy spread, women also began to take a stand in print in essays. Sarah Grimké wrote Letters on the Equality of the Sexes to respond to the accusations leveled at her sister Angelina and other public speaking women. It was a broad analysis and critique of the entire female experience in American society.

The Early Conventions on Women's Rights

Important for the growth of the women's rights movement and the idea of women's suffrage became the meetings that existed since the convention held in 1848 in the small town of Seneca Falls, New York. Some women who had worked to free slaves and wanted to appear in public were prevented from doing so because they were women. They were not allowed to appear in public, much less speak; addressing a mixed audience of men and women was completely unthinkable and against convention. But this was now changing around the middle of the century.

Seneca Falls Convention

→ Main article: Seneca Falls Convention

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, along with other supporters and followers of abolitionism, had made a long journey to the World Anti-Slavery Convention of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1840. There they experienced that despite days of debate on the topic of "women's participation in the convention," they were not allowed. They were not allowed to speak or vote, only to listen from the gallery. On this occasion, Stanton and Quaker Lucretia Mott became friends and vowed to each other to hold a women's rights convention back home in the States. It was then some eight years before the opportunity arose in 1848.

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first gathering of American women to make women's rights the sole issue. It was a meeting organized only by women. It was held in the western part of New York State, in the small town of Seneca Falls, New York, on July 19 and 20, 1848. At the end, a manifesto that became famous was issued, the Declaration of Sentiments.

This manifesto has been described by Judith Wellman, a historian, as "the single most important factor in spreading news of the women's rights movement around the country in 1848 and into the future."

(German: "the most important factor in the spread of the women's rights movement throughout the country, both in 1848 and in the period that followed.")

Before beginning the enumeration of "sentiments," or perceived injustices, Stanton formulates the following famous phrase:

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world:

(German: Die Geschichte der Menschheit ist eine Folge von wiederholten Ungerechtigkeit und Übergriffen von seiten des Mannes gegenüber der Frau, mit der klaren Absicht, eine absolute Tyrannei über sie zu errichten. To prove this, facts are to be presented to the well-meaning public).

An excited debate arose in the treatment of women's suffrage, which was especially dear to Stanton's heart. Many - Mott included - urged that this concept of women's suffrage be omitted. But Frederick Douglass, who attended alongside other men and was the only African American, argued persuasively for its retention. In the end, exactly 100 of the 300 or so people present signed the document, most of them women.

National Conventions

The National Women's Rights Conventions were almost annual events in the United States in the mid-19th century that made the early women's movement increasingly visible to the public. The first convention was held in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1850 and brought together both male and female advocates; the twelfth and last regular one was held in Washington, D.C., after the Civil War in 1869.

Those involved also received widespread support from the temperanceists - who did not achieve the 18th Amendment to the Constitution until 1919 - and the abolitionists. Speeches were made about equal pay, educational improvements and career opportunities, women's property rights, marriage reform, and alcohol prohibition. But the main topic discussed at the meetings was the passage of laws that would allow women the right to vote.

The outbreak of the War of Secession ended these annual gatherings and shifted the emphasis of women's activities to the emancipation of slaves. Susan B. Anthony could not convince women's activists to hold another convention focused solely on women's rights. Instead, the first Woman's National Loyal League Convention was convened at the Church of the Puritans in New York City on May 14, 1863. And they managed to get 400,000 signatures by 1864 on a petition to the United States Congress calling for the passage of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery.

However, many women became aware that after the liberation of the slaves, the problem of liberating women from the "slavery of the man" in marriage and family would come back on the agenda.

Emergence of women leaders

Beginning with the Seneca Falls Convention and continuing through the 12 years of National Conventions that followed, a social movement developed that produced an impressive array of women leaders in the New England states, Pennsylvania, New York, and the Midwest:

- Lucretia Mott (1793-1880) was an experienced and gifted speaker as a Quaker, and together with Elizabeth Cady Stanton she convened the Seneca Falls Convention.

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) was a headstrong and intelligent woman who particularly distinguished herself in parliaments with astute arguments concerning laws on the property rights of married women.

- Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) was Stanton's constant aide, a tireless organizer in the cause of women as well as temperance and slave emancipation.

- Lucy Stone (1818-1893) had already founded a women's debating club at Oberlin College and then lectured on women's rights. She was the leading woman at the first National Convention in 1850.

- Frances Dana Barker Gage (1808-1884) was a mother of eight who petitioned the Ohio legislature to have the phrase "white and male" erased from a new constitution.

- Hannah Tracy Cutler (1815-1896) was denied a degree by her father, so she studied theology and law in her home with her husband, who was enrolled at Oberlin. Later, by then widowed and the mother of three children, she was able to take a course of study at Oberlin herself. She gave a series of lectures in London on women's rights in 1851.

- and many more ...

·

Lucretia Mott

·

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

·

Susan B Anthony

·

Lucy Stone

·

Frances Dana Barker Gage

The cohesive movement around the leaders began to take shape, with discussion, debate and argument, leading to the development of a shared belief and ideology. This not only contained the generally approved goals, but also led to the development of a broad-based approach. A learning process was set in motion and women leaders - each with their own following - crystallised. These again became role models for new followers. Thus a system of communication developed with appropriate "heroines" or role models; the components of a social movement came together.

Small advances could be reported in every convention: Changes in state laws, congressmen converted to woman suffrage, or newspapers reporting favorably. By 1860, a friendly press had developed and a more serious public debate had begun. But no one had yet addressed or solved the central problem: men made all the laws. How could or should they be persuaded to share power? For in order to come to power, women needed the right to vote, which only men possessed and, out of deeply held convictions, refused to share. It would be many years before an answer to this question was found.

Sarah Grimké, author of Letters on the Equality of the Sexes.

This is the reconstructed historic site of the meeting in Seneca Falls

A memorial to three women leaders: Elizabeth, Lucretia and Susan (l. to r.)

Women's suffrage movement before and after the Civil War - 1860 to 1896.

→ Main article: War of Secession

By 1860, there had already been some changes in federal laws regarding women's property rights; a considerable expansion of girls' education and women's education had taken place. But still the male ideal of a "true woman" was the pious, obedient, and domestic wife who saw her husband as her guardian and protector and who essentially limited her sphere of action to her home and family.

And most of the women concerned were frightened by the fact that the braver sexes were gradually trying to break the taboos of the male-dominated society. Even if they applauded inwardly or in private, they were too afraid to do it publicly.

Political development and alternatives

With the Civil War and the subsequent period of reconstruction of the entire state, i.e. the Reconstruction Era, which lasted until 1877, new complications arose. During this time, women had to put their concerns about participation in elections on the back burner because there were more pressing matters to be dealt with.

The organization of the Women's National Loyal League had, after all, been founded to push through the 13th Amendment (in the 1865 version). 400,000 petition signatures were instrumental in getting the Amendment passed. With it, slavery was abolished.

Then most of the women were also concerned with establishing the right to vote for the former slaves. They thought they were also pursuing their own interests by doing so. If they saw themselves as a kind of "slave of the husband", they hoped that the other women would also come to this realization.

Among other things, the 14th Amendment forbade withholding the right to vote from male citizens. This now included the former male slaves, who were now allowed to vote in all states.

The 15th Amendment translates as:

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or restricted by the United States or any State on the ground of race, color, or former servitude."

Unfortunately, in the eyes of many women, the addition of "of the sex" was missing.

Even with the combination of all these new amendments, lawsuits all the way to the Supreme Court failed to win women's suffrage over the next few decades. The Supreme Court put an end to the so-called "strategy of departure" in Minor v. Happersett, ruling: "The Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon anyone. (The Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon anyone.)

Splitting up the women's rights movement

The founding of the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) in 1866, following the 11th National Women's Rights Convention, was an aberration and failure for a number of reasons, One was trying to achieve women's suffrage at a time when the primary concern - mainly in the eyes of many men - was to secure suffrage for the freed slaves, i.e., male African Americans.

AERA conducted two main campaigns in 1867. In New York State, which was in the process of revising the state constitution, it sought petitions for women's suffrage and to abolish property requirements for voting. In Kansas, she campaigned for referendums seeking the right to vote for both African Americans and women. The two goals could not be reconciled, For abolitionists believed that demanding women's suffrage would be a direct obstacle to achieving the right to vote for blacks. There were also differing views on this in the women's movement.

AERA continued with its annual meetings, but growing differences made cooperation difficult. Disappointment with the proposed 15th Amendment was especially great because of its failure to include the phrase "of the sex," The 1869 AERA meeting already signaled the end of the association.

In May 1869, Anthony, Stanton, and others founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). In November 1869, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe, Henry Blackwell, and others, many of whom had already helped found the New England Woman Suffrage Association a year earlier, formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Over the next 20 years, the rivalry between these two organizations created a partisan atmosphere that even had a distorting effect on the historical narrative of the women's movement.

The immediate reason for the split was the proposed 15th Amendment, which precisely still did not allow women the right to vote because it lacked the suffix "of sex." The two organizations differed - due to their leaders - primarily in their future course of action. Stanton and Anthony wanted to aggressively challenge women's ideology of "the sanctified home and motherhood" and saw women's suffrage as a remedy. They took every opportunity to make dramatic appearances and became very well known as a result. Stone and Blackwell did not want to inspire fear in their supporters. They relied on the solid information in their Woman's Journal and on quiet work in the individual states that would gradually lead to more and more women's suffrage laws in those individual states.

Political experiments and trials

1872: Anthony (along with several other women) participated in an election in Rochester that resulted in her being tried and fined. Because she did not pay it and the court did not collect the fine, the case could not be taken all the way to the Supreme Court.

The aforementioned Minor v. Happersett case, which went before the Supreme Court, concluded that there was no right in the Constitution for women to vote. In the 1875 dispute, the Supreme Court ruled that the Privileges or Immunities Clauses of the 14th Amendment did not mean or protect a woman's right to vote.

1876: Presentation of the "Women's Declaration of Rights" at the Philadelphia Centennial Celebration. Anthony's petition was referred by senators to a committee without jurisdiction. Everything came to nothing.

1878: Senator Aaron Sargent of California introduced an amendment to Congress that would not be ratified until 1920 as the 19th Amendment, 42 years later. It translates as:

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to carry this amendment into execution by appropriate laws."

Social change: growth of women's organisations

→ Main article: Social change

The last third of the 19th century, the age of industrialization, saw many important social changes and developments. Women as a whole acquired higher education and training. Many associations were formed that also catered to the needs of women in society. Women met in clubs and charities.

The most important association was the WCTU, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. This association was not only concerned with banning the production and distribution of alcohol. Under the leadership of Frances Willard, the WCTU also mobilized conservative women for the course towards women's suffrage and for other socio-political issues.

By the time Willard was elected WCTU president in 1879, the WCTU had grown to become the largest women's organization in the country, with 27,000 members. Under Frances Willard's leadership, the WCTU fought for women's suffrage and the eight-hour day, led the temperance movement, supported the kindergarten movement, advocated prison reform, called for model institutions for handicapped children, and promoted federal aid in general education and vocational training. She advocated Christian socialism, joined the Knights of Labor in the fight for the eight-hour day, and organized in the ProhibitionParty in 1882 to campaign against the sale of alcohol.

These many new associations were a kind of training schools for women. They learned organization, leadership, public speaking, and how to represent common interests. Many members were equally well connected with the two women's rights clubs and their leaders were equally welcome.

Reunion of the women's rights movement 1890

The AWSA had originally been the stronger of the two rival women's rights organizations, but was losing strength and effectiveness by the 1880s. Stanton and Anthony, the leading figures in the rival NWSA, were far better known and set the movement's goals; sometimes using daring tactics. Anthony, for example, interrupted official celebrations of the 100th anniversary of the U.S. Declaration of Independence to present her NWSA's "Declaration of Rights of Women."

Over time, the two organizations became closer again, as the younger members did not understand at all why there was such animosity among the older leaders. Further, in 1887, the NWSA's hopes for a federal woman suffrage amendment were finally dashed when the Senate voted against it. There was a renewed focus on the individual states, where efforts had not yet led to much success either. Women's suffrage had been achieved in two states, Colorado and Idaho.

Alice Stone Blackwell, daughter of AWSA leaders Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell, had great merit in her efforts to bring the two organizations together. In 1890, the two organizations merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The women's movement waned in strength and effectiveness after the merger. When Carrie Chapman Catt became chair of the organizing committee in 1895, she began to revitalize the organization. She developed work plans with clear goals for each state and calendar year. Although she replaced Anthony as chair in 1903, she had to withdraw from association activities for several years because of her husband's illness. It was not until 1915 that Catt returned to the chairmanship, replacing Anna Howard Shaw, who had not been a good administrator, and was allowed to appoint her own executive team. She transformed the formerly loosely structured organization into a highly centralized and effective association. But many years had passed, society and the economy had changed greatly.

Carrie Chapman Catt

Frances Willard, one of the most famous women in the United States...

Susan B. Anthony around 1900

Questions and Answers

Q: When did women's suffrage begin in the United States?

A: Women's suffrage began slowly at the state and local levels during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Q: When did women's right to vote become constitutional?

A: Women's right to vote became constitutional in 1920 with the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Q: What is women's suffrage?

A: Women's suffrage is the right to vote.

Q: How did women's suffrage happen in the United States?

A: Women's suffrage happened slowly at state and local levels during the 19th and early 20th centuries until the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed in 1920.

Q: What does the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution provide?

A: The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides, "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex."

Q: What did the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution do?

A: The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution gave women the right to vote at the national level.

Q: Were there any limitations to women's suffrage after the Nineteenth Amendment?

A: There were no limitations to women's suffrage after the Nineteenth Amendment, but some states attempted to impose voting restrictions that affected women and minorities.

Search within the encyclopedia