Witch (word)

![]()

This article is about the witch in mythology. For other meanings of witch or witches, see Witches; for the car brand witch, see Witch (car brand).

In fairy tales, myths and popular belief, a witch is a woman endowed with magical powers who can cast harmful spells.

In European culture, since the late Middle Ages, it has classically been seen in terms of a connection in the form of a pact or bogeyman with demons or the devil, with other criteria added as well.

The term is also used as a derogatory term or swear word for a vicious, quarrelsome, unpleasant or ugly female person.

In classical antiquity, "witches" appear as sorcerous human women, such as Kirke and Medea, who were said to be able to enchant people and animals with magic and poisons. Ovid, in the Fasti of Strigae, told of anthropomorphic, witch-like female figures; and Horace invented Canidia, a fictitious witch, who in this story, however, already wants to exercise the familiar term of infanticide in order to brew a love potion. At the time of the witch hunts, the term witch or sorcerer was occasionally applied as a foreign term to women and men who were persecuted on the charge of sorcery ("witchcraft"). Later, it became generally accepted, especially in the scientific study of the phenomenon "witch hunt".

For the application of the term to men as "sorcerers" or "warlocks," see also sorcerer.

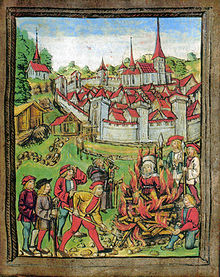

Burning of Anna Vögtlin as a witch in front of the lower gate of Willisau (Switzerland), 1447

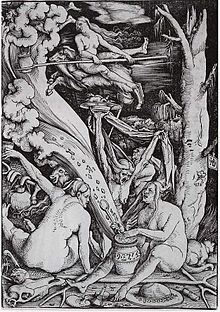

Hexentanzplatz in Trier (leaflet, 1594)

Witch scene (around 1700)

Real people as objects of speaking about witches

Historical development of the belief in witches

See also: Witchcraft

An essential element of the belief in witchcraft, also referred to as witch mania, is that the believer is not prepared to accept the category of "coincidence" as a possible explanation for outstanding events. According to Wolfgang Behringer, it is less the belief that witchcraft must be involved here that is astonishing and in need of explanation than the extent of the "disenchantment" of the modern world, i.e. the great extent of the willingness to evaluate, for example, the sudden death of an infant as mere bad luck.

The belief in witches is a pan-European superstition (popular belief), whose roots lie in the pre-Christian belief in gods. However, it is also still widespread in African cultures, animistic religions, etc. This far-reaching agreement is not obvious, because the terms are regionally different. Thus in the post-Celtic cultural sphere there is talk of fairies (Morgane etc.), who could be good and evil, in Ireland were depicted as two-faced. In the post-Germanic area the term fairy stands primarily for a good being, while otherwise there is rather (probably as a result of Christian indoctrination) the evil witch. The terms fairy and elf were not applied to humans and thus were not the subject of witch hunts. They retained their character as mythical beings.

The fairy-tale stereotype of the witch, namely an old woman riding a broom - often accompanied by a black bird (probably one of Odin's two ravens) or a black cat - derives from the idea of a creature that resides in hedgerows or rather in groves or rides on borders. Presumably the stereotype as such is relatively recent and indebted to illustrations in German storybooks, as exact equivalents (other than the ability to fly) are lacking in many places in neighbouring countries. The fence pole, usually forked branches, became the witch's broom in pictorial representations. This version, however, was already subject to Christian influence. There are various explanations for the image of the fence rider: On the one hand, it could have been a kind of archaic (forest) priestess, on the other hand, an abstract image is also invoked: beings sitting on fences are on a border from cultivated space to uncultivated nature.

If the hedge can perhaps be identified with the spell circle that surrounded pre-Christian places of worship and represents a dividing line between the world of this world and the world beyond, the witch is a person who can mediate between the two worlds. She thus possesses divinatory, but also healing abilities and high knowledge, and thus has the characteristics of the pre-Christian cult bearers.

From time immemorial the meanings oracle-speaker, spell-speaker, (clairvoyant) seer and others have been included in the designation witch - all attributes that were also assigned to the Nordic Freya, the Irish Brigid and other archaic goddesses.

One possible origin of the archetype "witch" is, if the etymology of the English witch is correct, a woman with occult or natural healing knowledge who may have belonged to a priesthood. This is a transfer of the abilities (healing, spellcasting, divination) of the goddess Freya and comparable goddesses in other regions to their priestesses, who continued to act in the usual manner for a long time in the early Christian environment. With the advance of Christianity, the pagan teachings and their followers were demonized.

The term "belief in witches" is, moreover, ambiguous. It describes not only the conviction of the real and threatening existence of witches, as it was rooted in popular belief and could increase as a reaction of the authorities to the witch craze. In addition, today it can describe the (natural-religious) beliefs that refer to a pre-Christian understanding and call certain people of both sexes, who allegedly have special abilities and knowledge (see: esotericism), witches.

Ancient

In the Old Testament of the Bible sorcery is threatened with the death penalty. Especially the passage (2 Mos 22,17 LUT) - you shall not let the sorceresses live - later served as justification for the persecutors of the witches.

In the 13th century BC, the Hittite Great King Muršili II accused his stepmother and reigning Great Queen Tawananna of having caused both his speech impediment and the death of his wife through witchcraft.

Also in many ancient cults there was already the image of the harmful sorceress and herbalist sorceress. Examples include the figures of Kirke and Medea in Greek mythology. Both are powerful sorceresses with herbal knowledge and various magical abilities that they use to help or harm.

The ancient goddess Hecate, in particular, was strongly associated with ancient witchcraft beliefs. Originally she was considered a benevolent and charitable goddess, but from the 5th century BC she became the patroness of all magical arts. She was believed to lead sorceresses and teach them their arts. The witch imagery of ancient Greece is strongly reminiscent of the witch imagery that emerged in the late Middle Ages and early modern period (the ability to transform, the casting of spells, witch flight, herbal knowledge, human sacrifice, and corpse abuse).

In ancient Roman law, harmful sorcery (e.g., using curse tablets) was punishable.

Middle Ages and modern times

→ Main article: Witch hunt

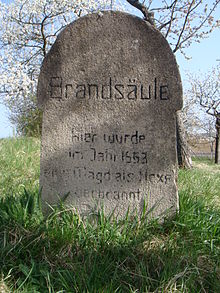

In the wake of the European Enlightenment, the persecution of witches was seen in many places as an evil to be overcome. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the practice, now condemned as cruel and inhumane persecution of human beings, was commemorated by the erection of monuments, such as the one on the outskirts of the small Saxon-Anhalt town of Eckartsberga, where a woman accused of witchcraft was consigned to flaming death in 1563.

Since 2002, the town of Schönebeck (Elbe) has honoured the women and girls who were sentenced to death as "witches" in Schönebeck and Bad Salzelmen and subsequently burned by naming them at a women's place in the "Schönebeck Memorial Park".

Geographical distribution of the witch hunt

Modern witch hunts were mainly concentrated in the territory of the Holy Roman Empire, England, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Lorraine, Scotland and Poland. Historians attribute this fact to the relatively weak position of central power in these countries. Spain, Portugal and Italy were largely spared the phenomenon of witch hunts. Individual cases are also documented in the American colonies (Salem witch trials) and for Finland. In the 17th century, almost 140 witch trials were held in Finnmark, the first in 1601.

Scandinavia

From earliest times, the Sami were considered to be particularly skilled in magic. Saxo Grammaticus writes:

"Sunt autem Finni ultimi Septentrionis populi, vix quidem habitabilem orbis terrarum partem cultura ac mansione complexi. Acer iisdem telorum est usus. Non alia gens promptiore jaculandi peritia fruitur. Gandibus & latis sagittis dimicant, incantationum studiis incumbunt, veationibus callent. Incerta illis habitatio est, vagaque domus, ubicunque, ferma occupaverint locantibus sedes. Pandis trabibus vecti, conferta nivibus juga percurrunt."

"The Finns are a people in the extreme north, who inhabit a scarcely habitable part of the globe, and cultivate the land there. The proficient use of spears is common among them. No other people derive better advantage from a practical knowledge of spear-slinging. They fight with heavy and thick arrows, they devote themselves to sorcery, and have experience in hunting. Their abode is not fixed, and their house is unsteady, wherever, take up their residence in the wilderness. On journeys they walk on curved planks through contiguous mountain ranges full of snow."

- Adam of Bremen: Saxonis grammatici historiæ Danicæ

and Adam of Bremen writes about Olav the Saint:

"Dicunt eum inter cetera virtutum opera magnum Dei zelum habuisse, ut maleficos de terra disperderet, quorum numero cum tota barbaries exundet, praecipue vero Norvegia monstris talibus plena est. Nam et divini et augures et magi et incantatores ceterique satellites antichristi habitant ibi, quorum praestigiis et miraculis infelices animae ludibrio daemonibus habentur."

"Among other virtuous achievements, he is said to have served God with such zeal that he extirpated from his country the sorcerers, who abound more than abundantly everywhere in the world of barbarians, but Norway is in a very particular degree full of such devilish beings. Here dwell fortune-tellers, fowlers, sorcerers, conjurors, and other servants of Antichrist, and their juggleries and arts make the unhappy souls the play-work of evil spirits."

- Adam of Bremen: Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum

and about the seeds he writes:

"Omnes vero christianissimi, qui in Norvegia degunt, exceptis illis, qui trans arctoam plagam circa oceanum remoti sunt. Eos adhuc ferunt magicis artibus sive incantationibus in tantum prevalere, ut se scire fateantur, quid a singulis in toto orbe geratur; tum etiam potenti murmure verborum grandia cete maris in littora trahunt, et alia multa, quae de maleficis in Scriptura leguntur omnia illis ex usu facilia sunt."

"Also all the inhabitants of Norway are good Christians, except those who live far to the north by the ocean. These are said to have such power by magic arts and incantations that they boast that they know what every man does in all the earth. They also draw great whales from the sea to the shore with effectual incantations, and they are accustomed to perform with ease many other things which are read of sorcerers in the Holy Scriptures."

- Adam of Bremen: Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae Pontificum

Sorceresses are already mentioned in the Icelandic sagas. The magic was usually related to causing severe storms or making clothing that no sword could penetrate. How the practices were performed is almost never described. One of the very rare accounts concerns the attempt of a woman skilled in magic to protect her wayward son from persecution by making his enemies go mad.

"Og er þeir bræður komu að mælti Högni: 'Hvað fjanda fer hér að oss er eg veit eigi hvað er?' Þorsteinn svarar: 'Þar fer Ljót kerling og hefir breytilega um búist.' Hún hafði rekið fötin fram yfir höfuð sér og fór öfug og rétti höfuðið aftur milli fótanna. Ófagurlegt var hennar augnabragð hversu hún gat þeim tröllslega skotið. Þorsteinn mælti til Jökuls: 'Dreptu nú Hrolleif, þess hefir þú lengi fús verið.' Jökull svarar: 'Þess er eg nú albúinn.' Hjó hann þá af honum höfuðið og bað hann aldrei þrífast. 'Já, já,' sagði Ljót, 'nú lagði allnær að eg mundi vel geta hefnt Hrolleifs sonar míns og eruð þér Ingimundarsynir giftumenn miklir.' Þorsteinn svarar: 'Hvað er nú helst til marks um það?' Hún kvaðst hafa ætlað að snúa þar um landslagi öllu 'en þér ærðust allir og yrðuð að gjalti eftir á vegum úti með villidýrum og svo mundi og gengið hafa ef þér hefðuð mig eigi fyrr séð en eg yður.'"

"And when the brethren came near, Högni said, 'What devil is coming there towards us? I know not what it is.' Thorstein answered, 'Here comes Ljot, the old woman, and she has dressed herself strangely.' She had thrown her clothes over her head in front and was walking backwards, stretching her head back between her legs. Ghastly was the look of her eyes, as they knew how to shoot it like the trolls. Thorstein called to Jökul, 'Now strike Hrolleif dead. You have long been burning for it.' Jökul answered, 'To that I am glad,' and cut off his head and wished him to the devil. 'Yea, yea,' said Ljot, 'now it was nigh that I might have avenged my son Hrolleif. But the sons of Ingimund are mighty men of fortune.' Thorstein answered, 'Why do you mean that?' She said she had meant to overthrow the whole country, 'and you would have gone mad, and stayed mad outside with the wild beasts. And so it would have come to pass, if you had not seen me sooner than I saw you.'"

- Vatnsdœla saga

When the English Mystery and Company of Merchant Adventurers for the Discovery of Regions, Dominions, Islands, and Places unknown tried to find the Northeast Passage to China, they abandoned the attempt because of pack ice and storms. This experience led to the English claim in the 17th century that there was a plague of witches in the north. On the ridge Domen near Vardö, one of the entrances to hell was identified in 1662 (another was the volcano Hekla in Iceland). The mountain was thought to be the meeting place of witches.

Sweden

In Elfdal, Dalarne, after the Thirty Years' War, the first burning of witches took place on August 25, 1669, and 84 adults and 15 children fell victim to it.

Norway

In total, there were more than 91 deaths after witch trials.

Justification and evaluation of the accusation of witchcraft

Old laws

The sagas already report that witches and wizards are to be punished because they use illicit, magical means to impose their will on others or interfere with nature to cause harm to others. For example, Eiríkr blóðøx is reported to have had 80 sorcerers burned. Among the South Germanic peoples, the preparation of potions causing female infertility was punishable by death. The minimum sentence for poison mixing, weather making and sorcery was seven years - if this was also connected with the service or pact with evil or at least supernatural powers, it became 10 years. From 800 onwards, the secular power shifted the investigation of these crimes more and more to the Church, which subsequently invoked Roman law of the imperial period, according to which the duty of denunciation applied against sorcerers and heretics as hostes publici. The popes of the High Middle Ages, such as Innocent III and especially Gregory IX, continued this and thus created the foundations of the Inquisition until 1233. This then no longer has anything to do with the mythological being of a witch or a person who knows magic; the accusation against mortal men consists of the combination of the offences of apostasy and heresy.

Early modern understanding of witchcraft

The characteristics of a witch, according to the witchcraft doctrine of early modern witch theorists, included:

- the witch flight on sticks, animals, demons or with the help of flying ointments

- Meeting with the devil and other witches at the so-called witches' sabbath

- the devil's bargain

- the sexual intercourse with the devil (in the form of incubus and succubus, the so-called devil's courtship) and

- the damage spell (cf. the term lumbago).

These five characteristics formed the elaborate witch code from about 1400.

The notion of limited goods played a role in damaging magic: if a farmer's harvest, milk yield or other goods fell, the cause was that someone had taken them away by magical means.

Women who practiced veterinary medicine were also quickly targeted by persecutors, as it was assumed that they had bewitched the cattle and thus achieved their healing successes (or, in the case of failures, it was immediately suspected that the treatment was merely intended to dry up the milk, etc.).

Especially women were accused of witchcraft. Part of the reason for this was the church's doctrine of original sin. It suggested that women were particularly susceptible to the whispers of the devil. The Hexenhammer claimed that women were inherently bad, and that the few good women were weak and more easily at the mercy of the devil's seductions; it was precisely in their function as midwives that they came into contact with bad juices that corrupted them and made them susceptible to the devil's seductions.

Of great importance was the idea of a general witchcraft conspiracy. From the transmission of stereotypes that had been attributed to the Jews for centuries, the idea of a "Synagoga Satanae" (Synagogue of Satan) was formed, later called "Witches' Sabbath". Here it was believed to be on the trail of an orgiastic gathering at which God and His Church were mocked. It was believed that the entire existence of Christianity was threatened by this "witch sect".

Thus, a mixed new understanding of witches emerged. It was no longer the harm that witches did that was their defining characteristic, but the apostasy from the faith and the associated turning to the devil. Now they constituted a spiritual danger; the church proceeded against its apostate believers, according to the principles of Augustine of Hippo, with coercion and fire for their salvation.

Belief in witches occurs in all cultures and continents and is closely associated with taboo aspects of female sexuality, fertility and reproduction, such as rejection of expected chastity (sexual hedonism, often associated with prostitution), birth control (understood as infanticide, which includes abortion), rejection or reversal of classical gender roles and socially prescribed norms. In sum, entities that rebelled against the disciplining of the body, the functionalization of sexuality, and the enclosure of communally administered land. The figure of the witch is also seen in contemporary interpretations as a symbol of resistance to the spread of capitalism and its forms of exploitation.

21st century

Evaluations of the major churches

There were two competing views of witchcraft in the late ancient and early medieval church. Augustine of Hippo inferred from the physical impossibility of casting spells an implicit invitation from the devil to accomplish the otherwise impossible task.

This semiotic view of witchcraft, however, initially took a back seat to a view derived from the regulations of the Church Fathers on the treatment of women who believed they went out at night with Diana: These women, they said there, were to be treated with leniency because, since what they believed they were doing was physically impossible, it was based on imagination. Charlemagne's regulations towards the Saxons are to be understood in the same way.

Later, the doctrine of the devil's pact was developed. Although almost 1000 years passed before organized persecution, this is one of the foundations that led to the persecution of witches. Later in the 15th century, the image of witches as a witch sect or cult with gatherings and rites that were supposed to lead to the takeover of world domination was consolidated (J. Baptier et al.). This, together with torture as a method of interrogation, later led to the explosion of accusations. The age of legal witch hunts had begun.

The Roman Catholic Church is opposed to witchcraft as well as other forms of magic and sorcery. According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, such practices are "gravely contrary to the virtue of the worship of God", even if they are intended to "procure health" (CCC 2117). The Protestant Church evaluates magic as an attempt to "make divine things technically available to [...] oneself" and as a violation of the first commandment. "Magic then becomes an illegitimate interference with the absolute freedom of God."

Legal valuations

Europe

With the European Enlightenment, criminal offences that penalise sorcery, magic and the like were abolished. The prevailing assumption is therefore that superstitious or unreal attempts are not punishable. However, this result is justified differently in terms of criminal law dogma. De iure, any behaviour in which the perpetrator "trusts in the efficacy of non-existent or, according to the state of scientific knowledge, in any case unverifiable magical powers" is considered "superstitious".

According to another view, the unreal attempt is to be put on the same level as the grossly incomprehensible attempt. According to this, the court can refrain from punishment or mitigate the punishment according to § 23 para. 3 StGB. Harro Otto wants to always refrain from punishment in a constitutional interpretation of § 23 para. 3 StGB. In terms of legal policy, it is demanded that the grossly incomprehensible attempt - as well as the unreal attempt - should be completely exempt from punishment, since both are neither worthy of punishment nor in need of punishment.

The Austrian Criminal Code provides in section 15(3): "Attempt and participation therein are not punishable if the completion of the act was not possible under any circumstances for lack of personal qualities or circumstances which the law presupposes in the person acting, or according to the nature of the act or the object on which the act was committed." The corresponding provision of the Swiss Criminal Code reads: "If the perpetrator, out of gross ignorance, fails to recognise that the act cannot be completed at all because of the nature of the object or the means on or with which he intends to carry it out, he remains unpunished."

Anyone in a constitutional state who wanted to convict someone of "summoning an angel of death" would have to prove that

- the conjuring of an angel of death is a criminal offence

- there are angels (here: angels of death),

- these are basically controllable by humans and

- the suspect belongs to the privileged group of persons for whom this is possible.

The thesis that jurists committed to the Enlightenment could not react to the attempt to harm people through sorcery by imposing a punishment is illustrated by Maximilian Becker with the words: "If at a holy place at midnight under a full moon, A puts a death curse on B, who is lying in bed at home, and B dies a few minutes later of a heart attack, no one would think of punishing A for a completed homicide." Nor does the person who prays, say, for the death of his neighbor, attempt to kill him, but only believes that he is trying to do so.

Africa and Asia

In Saudi Arabia, as recently as 2011, a woman was beheaded as a "witch" for claiming to be able to heal illnesses supernaturally and getting paid for her alleged abilities.

Until 2013, "witchcraft" could be punished by law in Papua New Guinea. Perpetrators who justified assaults on women by claiming that they had been "bewitched" by them could expect to be granted mitigating circumstances by the country's judiciary.

On 16 July 2008, the Federal Government responded to a major inquiry by members of the Alliance 90/The Greens parliamentary group on the subject of "Witchcraft and Sorcery in Africa":

In the African countries that criminalize "witchcraft" and "sorcery", there is no uniform practice with regard to the application of the corresponding penal law paragraphs. In some countries, prosecution is generally carried out on the basis of the relevant legal provisions (Gabon, Malawi, Namibia, Zambia, Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo); in other countries, prosecution is in most cases not carried out despite the existing legal basis. In a number of countries, acts associated with "witchcraft" and "sorcery" are only punished if they are also criminal offences, such as murder, assault, disturbance of public order (Benin, Côte d'Ivoire, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, Chad and Uganda). Ghana and Sudan are special cases. In Ghana, despite the absence of criminal laws, women are persecuted on arbitrary charges. Non-governmental organizations estimate the number of women deported to so-called "witch camps" at about 3,000. In Sudan, too, there are occasional outrages against women accused of "witchcraft" without the state adequately fulfilling its protective function.

The Federal Government is of the opinion that acts connected with "witchcraft" and "sorcery", which constitute an attack on the physical integrity of human beings, must be prosecuted under criminal law.

"New Witches"

The concept of witchcraft in the European-American cultural area has undergone a transformation away from the mainstream influenced by the Enlightenment. Margaret Alice Murray's book Witch-Cult in Western Europe ("Hexen-Kult in Westeuropa") published the concept of witchcraft in a new concept in 1921. With the reception of early research on the witch hunts (including Jules Michelet in his less systematic than intuitive-romantic historical work La Sorcière) by an alternative scene and the women's movement, especially the idea that the witches were actually "wise women" who were persecuted by the rulers, the witch topos offers a wide spectrum of identification for neo-paganism and the esoteric scene.

The term witch is understood here in a positive new way. Nowadays, many women who deal with medicinal herbs and old European religions, among other things, call themselves witches.

Above all, the Wiccan religion should be mentioned here, which today sees itself as a new form of a pagan "nature religion" of witches, has many followers in the USA and is recognized as a religion there. The Celtic Witches refer specifically to roots in Celtic mythology and religion.

Male witches

Men today sometimes refer to themselves as a "witch", but also as a sorcerer, wizard or warlock.

The feminine and masculine expressions, however, do not originate from the same historical source and therefore evoke different associations in each case.

Witch Children (Congo)

Since 2000, economic and social disintegration has led to the stigmatization of children as witch children in the Democratic Republic of Congo, but also in Nigeria, Togo, Tanzania and other African countries. These children are believed to have magical abilities with which they are supposed to cast harmful spells. Children stigmatized in this way are often abandoned by their mothers, persecuted and murdered.

Wiccan ceremony in Avebury (May 2005)

The Night-Hag Visiting Lapland Witches by Johann Heinrich Füssli

"The Witches", woodcut by Hans Baldung (1508).

Memorial stone for a witch burning 1563 in Eckartsberga

Famous (alleged) witches

Authentic people

- Joan of Arc, burned in Rouen 1431

- Margaret Barcley († 1618), a lady of a good Scottish house, was tried, tortured and condemned as a witch at Irvine (Ayrshire). She was strangled and burned.

- Sidonie von Borcke (1548-1620) from the virgin convent of Marienfließ was beheaded and burned at the stake in front of the mill gate on 28 September 1620.

- Elisabeth von Doberschütz, née von Strantz, wife of the former town captain of Neustettin Melchior von Doberschütz, was beheaded and burned at the gates of Stettin on 17 December 1591.

- The "Child Witch" Agatha Gatter

- Anna Göldin, executed in Glarus in June 1782 as the last witch (in Switzerland).

- Maria Holl, (1549-1634), the "Witch of Nördlingen", was one of the first women to withstand all the tortures during the witch trials against her in 1593/1594. Through her strength she freed the city of Nördlingen from the witch craze. Her steadfastness led to doubts about the correctness of witch trials and ultimately to a rethinking of the population and the authorities.

- Hester Jonas, called "the witch of Neuss", was arrested in 1635, tortured on the witch's chair and beheaded and burned in front of the windmill in Neuss on Christmas Eve 1635 at the age of about 64. The complete protocol of the trial is preserved in Neuss.

- Katharina Kepler, mother of Johannes Kepler, released in 1621.

- Catherine Monvoisin, known as "La Voisin", and her Parisian coven supplied Madame de Montespan, Louis XIV's mistress, and his court with poison and held black masses in return for payment. In 1680, she and her followers were burned at the Place de Grève.

- Tempel Anneke, civil name Anna Roleffes, was one of the last "witches" sentenced in Brunswick and executed there on 30 December 1663 after nine months of imprisonment and numerous interrogations in front of the Wendentor.

- Anna Schnidenwind, née Trutt (* around 1688 in Wyhl am Kaiserstuhl; † 24 April 1751 in Endingen am Kaiserstuhl) was one of the last women to be publicly executed as a witch in Germany.

- Anna Maria Schwegelin (also: Schwägele, Schwegele, Schwegelin; * 1729 in Lachen; † 1781 in captivity in Kempten) was a maid who was sentenced to death in 1775 as the last "witch" in the territory of present-day Germany. It has since been proven that, contrary to older belief, the sentence was not carried out and Schwegelin died in captivity.

- Anna Truels, burned to death on the North Frisian island of Nordstrand in 1567.

- Abigail Williams, one of the witches of Salem (USA). Salem is known for the witch trials that took place in 1692. This fact earned the city the nickname The Witch City.

Fictional witches

- Atsuko Kagari, main character of the Japanese animated series Little Witch Academia

- Bibi Blocksberg, main character of the radio play, animated cartoon and feature film series of the same name

- Gundel Gaukeley, minor character in the Walt Disney universe.

- Madame Mim, minor character from the Walt Disney universe and in the film The Witch and the Wizard.

- Sabrina Spellman, Zelda Spellman & Hilda Spellman main characters of the TV series Sabrina - Totally Verhext! , Simsalabim Sabrina Sabrina - Bewitched Again! and Chilling Adventures of Sabrina

- The little witch, main character in the novel of the same name by Otfried Preußler

- The witch Schrumpeldei by Eberhard Alexander-Burgh

- Bilwis Babelin from the book for young people Unter Gauklern by Arnulf Zitelmann

- Nanny Ogg, Grandma Wetterwachs and Magrat Knobloch, characters from the Discworld novels by Terry Pratchett.

- Angela Spook, art figure of the street artist Angelika Tampier (1954-2020), who performed on Düsseldorf's Königsallee (at the Kö-Center).

- The witches in the novel Witches Witch by Roald Dahl and the 1990 and 2020 film adaptations of the same name.

- Samantha Stephens, main character of the TV series Falling in Love with a Witch.

- Willow Rosenberg, one of the main characters in the television series Buffy - Under the Spell ofDemons.

- Prue, Piper, Phoebe, Paige, main characters in the TV series Charmed - Enchanting Witches

- The Witch of Blair, subject of the feature film Blair Witch Project.

- Will, Irma, Taranee, Cornelia, and Hay Lin, main characters in the comic book and television series W.i.t.c.h.

- Kiki, main character from the Japanese anime feature film Kiki's Little Delivery Service

- Mildred Hoppelt, main character of the children's book and TV series A Lousy Witch, as well as her friends Mona Mondschein, Edith Nachtschatten and other characters.

- Hermione Granger, one of the main characters in the Harry Potter novels, as well as other characters in the novels.

- Geloë, character of the novel trilogy The Secret of the Great Swords

- Serafina Pekkala, minor character in the His Dark Materials trilogy of novels.

- Ursula, antagonist in the movie Arielle the Mermaid

- The main characters of the anime series Magical Doremi are students of the cursed witch Majorika.

- Lady Grey and the witch organization WWS in the novels Witching Three and Hunting Time by Claudia Toman

- Bayonetta, main character of the video game of the same name

- Jeanne, minor characters of the video game Bayonetta

- Alicia Claus, main characters of the video game Bullet Witch

- Elphaba Thropp, the "Wicked Witch of the West" in the novels Wicked, Son of a Witch and A Lion Among Men by bestselling U.S. author Gregory Maguire, also the main character in the Broadway musical Wicked

- Hope Mikaelson, Lizzie Saltzman and Josie Saltzman, the main characters in the series Legacies, a spin-off of Vampire Diaries and The Originals

- Bonnie Bennett, one of the main characters in the television series Vampire Diaries.

- Freya Mikaelson and Davina Claire from the TV series The Originals

- Macy, Melanie, and Maggie, main characters of the Charmed reboot (television series).

- Icy, Darcy and Stormy, antagonists of the animated series Winx Club

- Regina Mills, Emma Swan, Zelena, Cora Mills, Ingrid, Maleficent, Ursula, Cruella de Vil, Drizella Tremaine, Anastasia Tremaine Alice and Gothel, characters from the series Once Upon a Time...

- Lena Duchannes, main character of the fantasy novel Sixteen Moons - An Immortal Love, who calls herself a "caster," meaning a higher-ranking witch

Witch figures in different cultures

- Baba Jaga, witch in (East) Slavic mythology and fairy tales

- Jenny Greenteeth, River Witch from English Folklore

- Louhi, Witch of the Northland in the Finnish Kalevala Mythos

- Ragana, Lithuanian and Latvian witch

- yamauba, japanese mountain witch

- Yuki Onna, Japanese Snow Witch

- Grýla, Icelandic witch figure

Witches and covens in world literature

- William Shakespeare: Macbeth.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Walpurgis Night's Dream from Faust. Der Tragödie erster Teil.

- Theodor Fontane: The Bridge on the Tay

- Mikhail Bulgakov: The Master and Margarita.

- Sylvia Townsend Warner: Lolly Willowes

Angela Spook , the witch of the Düsseldorf Königsallee, 2008

Spark fire with witch puppet, near Görisried (2016)

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a witch?

A: A witch is a person who practices witchcraft or magic.

Q: What was the traditional usage of the word witch?

A: The traditional usage of the word witch was as an accusation to individuals who were believed to have bewitched or cast spells to control people.

Q: Who practices witchcraft and worships nature today?

A: Followers of Wicca practice witchcraft and worship nature.

Q: What do some practitioners of Wicca call themselves?

A: Some practitioners of Wicca call themselves witches.

Q: Are the practitioners of Wicca related to witches of historical context?

A: The practitioners of Wicca are completely unrelated to the historical witches mentioned in the article.

Q: How is the word "witch" used today?

A: The usage of the word "witch" today varies from person to person but it can be used in a positive manner by individuals who identify as witches.

Q: How has the connotation of the word "witch" changed over time?

A: The connotation of the word "witch" has changed over time from being used as an accusation to becoming a term used to describe individuals who practice magic and witchcraft.

Search within the encyclopedia