Witch-hunt

![]()

Witch hunter is a redirect to this article. For the British horror film, see The Witch Hunter and for the 2013 fantasy film, see Hansel and Gretel: Witch Hunters.

Witch-hunting is the process of tracking down, arresting, torturing and punishing (especially executing) people who are believed to be practicing sorcery or to be in league with the devil. In Central Europe it took place mainly during the early modern period. From a global perspective, the persecution of witches is still widespread today.

The peak of the wave of persecution in Europe was between 1550 and 1650. The reasons for the significantly increased mass persecution in some regions compared to the Middle Ages in the early modern period are manifold. For example, at the beginning of the modern era there was a multitude of crises such as the Little Ice Age, pandemic epidemics and devastating wars. Moreover, mass persecution could only occur structurally when individual aspects of magical belief were transferred into the criminal law of early modern states. An interest in the persecution of witches or pre-Christian-Germanic patterns of interpretation, which attributed personal misfortune such as regional crop failures and crises to magic, existed in broad sections of the population. The persecution of witches was sometimes actively demanded and practiced against the will of the authorities.

Overall, it is estimated that three million people were tried in Europe in the course of the witch hunt, with 40,000 to 60,000 victims being executed. Women made up the majority of victims in Central Europe (about three quarters of victims in Central Europe) as well as denouncers of witchcraft and witches. In northern Europe, men were more affected. There is no clear connection between denominational affiliation and witch hunts.

Today, witch hunts are particularly prevalent in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America.

Burning of witches in 1587, depicted in the Wickiana

Ancient

Although the legal use of the term "witch" was not introduced until the beginning of the 15th century, the belief in sorcerers can be traced back to ancient civilizations. Magical practices were carefully observed and often feared as black magic. Both in Babylonia (Codex Hammurapi: water test) and in Ancient Egypt, sorcerers were punished. The Old Testament forbids sorcery (Lev 19:26 EU) and calls for the persecution of sorcerers (Ex 22:17 EU). However, the Bible does not know witches in the sense of early modern times. According to the Twelve Table Law of the Romans, negative sorcery was punishable by death (Table VIII). However, there was never a targeted persecution of alleged witches as later in the early modern period.

The ancient church was not involved in persecutions and rejected the beliefs and practices associated with witchcraft as superstition (Canon episcopi).

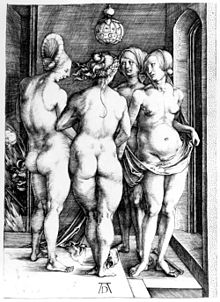

Albrecht Dürer 1491: The four witches

The fight against witch hunts

Criticism of witchcraft began practically immediately with the onset of modern persecution. In 1519, for example, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486-1535) successfully defended a woman accused of witchcraft before the inquisitor Claudius Salini in Metz.

Initially, there were reservations, especially from the legal and administrative sides, about the emergence of a special jurisdiction alongside the state judicial organs. Fundamental criticism of the belief in witchcraft did not set in until later.

Doubts about magic arts and criticism of the trial procedure

The interpretation of weather anomalies, which in popular belief were attributed to witches and sorcerers, during the "Little Ice Age" had a not inconsiderable influence on the development of intellectual history. Particularly in the environment of the University of Tübingen, a number of theologians and jurists were critical of the belief in witches, because God's omnipotence was seen as so comprehensive that there could be no weather magic or harmful magic: Ultimately, disaster, misfortune and bad weather were also directed by God himself, in order to punish sinners and to test the righteous. Harmful spells, witches' flight and witches' dance are diabolical fantasy. Witches could at most be punished because of their apostasy from God through the devil's pact.

To this circle from the environment of the Tübinger university belonged:

- Martin Plantsch (c. 1460-1533) from Dornstetten, who lived in Tübingen from 1477 to 1533, considered sorcery to be imagination as early as 1507, two years after a witch burning in Tübingen; the work of witches could not be fought because it was under God's will: "This is the first universal truth: no being can harm another or produce any actual outward effect unless by the will of God".

- Johannes Brenz (1499-1570) from Weil der Stadt, 1537 to 1538 in Tübingen, denied in 1539 the responsibility of witches for a great hailstorm, but considered their punishment justified if they imagined themselves and had the evil intention to be in league with the devil.

- Matthäus Alber (1495-1570) from Reutlingen, 1513 to 1518 in Tübingen, and Wilhelm Bidembach (1538-1572) from Brackenheim, in the mid-1550s in Tübingen, preached in 1562 in Stuttgart after a great hailstorm against the Esslingen pastor Thomas Naogeorg (1508-1563), who held witches responsible and demanded their severe punishment.

- Jakob Heerbrand (1521-1600) of Giengen an der Brenz, 1543 to 1600 in Tübingen, in 1570 put forward the disputation thesis on Ex 7:11-12 LUT that men can neither do magic nor make weather, and had this defended by his student Nikolaus Falck (1540-1616): "One must not think that these words of the 'magicians' have such great efficacy or that they have powers to bring about such things"-they are "phantasmata" that Satan feigns, but not real substantial changes in nature or harm to people, for only God's Word can actually have a creative effect.

- (Theodor) Dietrich Schnepf (1525-1586) from Wimpfen, 1539 to 1555 and 1557 to 1586 (with interruptions) in Tübingen, turned against the belief in witches in sermons around 1570.

- Jacob Andreae (1528-1590) from Waiblingen, 1541 to 1546 and 1561 to 1590 in Tübingen.

- Johann Georg Gödelmann (1559-1611) from Tuttlingen, 1572 to 1578 in Tübingen, presented as a jurist 1584 in Rostock for Marcus Burmeister disputation theses, in which he considered magic arts for "devil's spinning, deception and fantasy" and demanded the exact observance of the process regulations. In 1591 he published a corresponding three-volume work on the treatment of witches.

- David Chytraeus (1530-1600) from Ingelfingen, 1539 to 1544 in Tübingen, published in 1587 a Low German writing of Samuel Meiger (1532-1610) about the persecution of witches and spoke out in the preface for extreme restraint in the persecution.

- Wilhelm Friedrich Lutz (1551-1597) from Tübingen, 1567 to about 1576 at the University of Tübingen, spoke out against the witch trials in sharp sermons from 1589 in Nördlingen.

- Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) from Weil der Stadt, 1589 to 1594 in Tübingen, defended his own mother, accused as a witch, in 1615-1620 with the help of a legal opinion, which probably goes back to his friend Christoph Besold (1577-1638), 1591 to 1598 and from 1610 to 1635 in Tübingen.

- Theodor Thumm (1586-1630) from Hausen an der Zaber, 1604 to 1608 and 1618 to 1630 in Tübingen, limited in 1621 in his disputation theses for Mag. Simon Peter Werlin the punishability of witchcraft and pleaded for help for women deceived by the devil.

- Johann Valentin Andreae (1586-1654) from Herrenberg, 1601 to 1614 (with interruptions) in Tübingen, rejected pyres as punishment for witches in principle.

In other regions, too, there was criticism of witch trials as early as the 16th century, e.g. of the sentences imposed. For example, Anders Beierholm (ca. 1545-1619) from Skast, Lutheran pastor in Süderende on Föhr from 1569 to 1580, rejected the death penalty for sorceresses and tried to get the island's bailiff to stop burning witches. As a result, Beierholm himself was accused of sorcery by his opponents and was deposed as pastor on Föhr in 1580.

Fundamental rejection of the witch trials

The physician Johann Weyer (1515/16-1588) had a significant moderating influence with his 1563 paper De praestigiis daemonum ("On the Dazzling Works of Demons"). He accused Brenz and others of inconsistency: If there was no harmful magic, witches should not be punished. The (probably reformed) physician Weyer also argued against the belief in witches on the basis of God's omnipotence. Juristically, he was influenced by Andrea Alciato (1492-1550) and the humanist school of law at the University of Bourges.

Immediately after the publication of Weyer's book, Duke William V of Jülich-Kleve-Berg (1516-1592), Elector Frederick III of the Palatinate (1515-1576), Count Hermann of Neuenahr and Moers (1520-1578), and Count William IV of Bergh-s'Heerenberg (1537-1586) rejected further torture and the use of the death penalty; Count Adolf of Nassau (1540-1568) also held Weyer's opinion. Christoph Prob († 1579), the chancellor of Frederick III of the Palatinate, defended Weyer's view at the Rhenish Electors' Day in Bingen in 1563. However, witch hunts in these territories were not yet permanently stopped, but flared up again later.

In 1576, the execution of Catharina Hensel from Föckelberg, who had been condemned as a "sorceress", was cancelled because she recanted her confessions extorted under torture at the place of execution and protested her innocence. The executioner refused to carry out the execution for reasons of conscience, and the bailiff of Wolfstein and Lauterecken, Johann Eggelspach (Eigelsbach), stopped the execution. Count Palatine Georg Johann I of Veldenz-Lützelstein (1543-1592), who appointed Weyer's son Dietrich as chief bailiff in 1581/82, commissioned three expert opinions from advocates of the Speyer Imperial Chamber Court, including one from Franz Jakob Ziegler, who, under Weyer's influence as chief expert, recommended dismissal in 1580 against bail (sub cautione fideiussoria) and imposition of costs on the denouncing community.

The Reformed physician Johannes Ewich (1525-1588), who condemned torture and water testing in 1584, the Reformed theologian Hermann Wilken (Witekind) (1522-1603) in his pseudonymously published work Christlich bedencken vnd erjnnerung von Zauberey (1585), or the Catholic theologian Cornelius Loos (1546-1595) in his treatise De vera et falsa magia (1592), thought similarly to Weyer.

The English physician Reginald Scot (before 1538-1599) published the book The Discoverie of Witchcraft in 1584, in which he explained magic tricks and declared witchcraft irrational and unchristian. King James I (1566-1625) had the books Scots burned after his accession to England in 1603.

As early as 1597, the Reformed pastor Anton Praetorius, as princely court preacher in Birstein, had campaigned for the end of a witch trial and the release of the women. He railed against torture to such an extent that the trial was ended and the last surviving prisoner was released. This is the only surviving instance of a clergyman demanding and enforcing an end to torture during a witch trial. In the records of the trial, it says: "Because the pastor had been there again, torturing the women, it has been omitted." In 1598, Praetorius was the first Reformed pastor to publish the book Von Zauberey vnd Zauberern Gründlicher Bericht gegen Hexenwahn und unmenschliche Foltermethoden under the name of his son Johannes Scultetus. In 1602, in a second edition of the Gründlicher Bericht, he took the courage to use his own name as author. In 1613, the third edition of his report appeared with a personal preface.

Although Hermann Löher's Hochnötige Unterthanige Wemütige Klage Der Frommen Unschültigen did not appear until 1676, after the end of the harshest wave of persecution, it is significant insofar as the author himself had participated in the 1620s and 1630s as a more or less volunteer in the persecution apparatus and had only become an opponent of persecution as a result. In this respect, he offers an insider's perspective on the course of the trial and the power relations behind it, which is not to be found among the other opponents of persecution.

Before the Age of Enlightenment, the Jesuit Friedrich Spee von Langenfeld, professor at the universities of Paderborn and Trier and author of the 1631 Cautio Criminalis (Legal Concerns about the Witch Trials), was the most influential author to attack the witch trials. He was appointed confessor to convicted witches and, in the course of his work, came to doubt the witch trials as a means of finding guilty people. Fearing to be portrayed as a protector of witches and thus strengthening the party of Satan, he published it anonymously. His book was a response to the standard work on the theory of witchcraft by his Rinteln professor colleague Hermann Goehausen Processus juridicus contra sagas et veneficos from 1630.

In 1635, Pastor Johann Matthäus Meyfart, a professor at the Lutheran theological faculty in Erfurt, opposed witch trials and torture in his book "Christliche Erinnerung, An Gewaltige Regenten, vnd Gewissenhaffte Praedicanten, wie das abscheuwliche Laster der Hexerey mit Ernst außzurotten, aber in Verfolgung desselbingen auff Cantzeln vnd in Gerichtsheusern sehr bescheidlich zu handeln".

The Protestant jurist and diplomat Justus Oldekop openly and resolutely opposed not only the "abominable and barbaric procedure" of the trials themselves, but also, with remarkably modern conviction, the well-founded witch craze behind them - only shortly after Friedrich Spee and thus decades before the actual Enlightenment.

Around 1700, when witch hunts had already become rare, the German jurist Christian Thomasius published his writings against the belief in witches. He observed that the accused only "confessed" when they could no longer endure the torture. On the basis of the book De crimine magiae, which he wrote on the subject in 1701, King Frederick William I (Prussia) issued a mandate on December 13, 1714, drawn up by the minister v. Plotho, which restricted the witch trials to such an extent that no further executions took place.

However, the famous physician Friedrich Hoffmann from Halle was still convinced at the beginning of the 18th century of the possibility of witches conjuring up diseases in conjunction with the supernatural powers of the devil.

The process of rethinking was completed in the times of the Enlightenment. With legal practice turning away from oaths and divine judgement towards provability, the non-provability of supernaturally caused harm led to witchcraft accusations no longer being pursued, although parts of the population continued to demand this for a long time.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a witch hunt?

A: A witch hunt is a search for witches to capture.

Q: What type of behavior often accompanies a witch hunt?

A: Witch hunts often involve moral panics or mass hysteria.

Q: How common are witch hunts today compared to the past?

A: Witch hunts were much more common in the past than they are today.

Q: Who typically participates in witch hunts?

A: Many different groups participated in witch hunts, including Christians.

Q: What was the goal of a typical witch hunt?

A: The goal of a typical witch hunt was to capture witches.

Q: How long have people been participating in witch hunts?

A: Witch hunting has been around since ancient times and has continued into modern day, although it is much less common now than it used to be.

Q: Are there any other activities associated with witchcraft besides hunting them down?

A: Yes, some people practice witchcraft as part of their spiritual beliefs and rituals, such as Wicca and Paganism.

Search within the encyclopedia