Winter War

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Winter War (disambiguation).

The Winter War (Finnish talvisota, Swedish vinterkriget, Russian Зимняяя война Simnjaja woina) was fought between the Soviet Union and Finland from 30 November 1939 to 13 March 1940. It is also known as the Soviet-Finnish War (Russian Советско-финская война Sovetsko-finskaya woina) or "Soviet-Finnish War" (Russian Советско-финляндская война Sovetsko-finlyandskaya woina).

In the autumn of 1939, the Soviet Union had confronted Finland with territorial claims in the Karelian Isthmus, justifying them with indispensable security interests for the city of Leningrad. After Finland rejected the demands, the Red Army attacked the neighbouring country on 30 November 1939.

The original war goal of the Soviet Union was presumably the occupation of the entire Finnish territory in accordance with the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact. However, the attack was initially stopped by the Finnish forces, which were considerably outnumbered and outgunned. Only after extensive regrouping and reinforcements could the Red Army begin a decisive offensive in February 1940 and break through the Finnish positions. On March 13, 1940, the parties ended the war with the Moscow Peace Treaty. Finland was able to maintain its independence, but had to make considerable territorial concessions, in particular ceding large parts of Karelia.

Winter War

Karelian Isthmus1

. Summa - Taipale (Kelja) - 2nd Summa - Honkaniemi - Wiborg Bay

Ladoga-KareliaTolvajärvi

- Kollaa

KainuuSuomussalmi

(Raate Street) - Kuhmo

LaplandSalla

- Petsamo

Some 70,000 Finns were wounded or killed in the conflict. The magnitude of Soviet losses is disputed; it is estimated to be many times higher. The course of the war revealed weaknesses in the Red Army which, on the one hand, prompted the Soviet leadership to undertake comprehensive reforms and, on the other, contributed to a momentous underestimation of the Soviet Union's military strength in the German Reich. In Finland, the military defensive successes helped to soften the social divisions that had become apparent during the Finnish Civil War.

Course of the Winter War

Causes and initial situation

Background from the Finnish point of view

Finland had been integrated into the Russian Empire as a Grand Duchy since 1809. In the face of several attempts at Russification, the Finns retained their cultural independence and a certain political autonomy within the autocratic system. The Finnish independence movement gained strength after the outbreak of the First World War. As the Russian Empire sank into the Russian Civil War following the October Revolution and the Bolshevik takeover, Finland declared its independence in December 1917. Since Lenin did not see Finnish independence as a threat to Soviet rule, unlike the White Armies in Russia, he recognized Finland as a sovereign state in January 1918.

Shortly afterwards, independent Finland was shaken by civil war, triggered by an attempted coup by socialist forces supported by the Russian Bolsheviks. Bourgeois forces led by Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim succeeded in winning the war with German help. Most of the socialist leadership fled to Russia. Bourgeois Finland interpreted the Civil War primarily as a war of liberation against Russia. Relations between the two states remained strained in the aftermath. Efforts to create a Greater Finland and the associated territorial claims against the eastern neighbour contributed to this in particular. In several eastern war campaigns between 1918 and 1920 irregular Finnish military units tried unsuccessfully to annex the Soviet parts of Karelia to Finland. In 1920, the two states sealed the end of hostilities in the Peace of Dorpat. However, the Greater Finland idea lived on. The Academic Karelia Society (Akateeminen Karjala-Seura), which was founded in 1922 and to which numerous prominent people from politics and science belonged, openly carried out propaganda for the annexation of East Karelia.

Relations between the two countries in the period that followed were "correct but cool". At the beginning of 1932, the neighbours concluded a non-aggression pact. However, this did little to reduce mutual distrust. In the worsening clash of interests between the Soviet Union and Germany, Stalin tried in vain to bind Finland more closely to himself through further treaties. The classification of Finland as belonging to the capitalist camp, the propaganda of the Karelian Academic Society and the emphatically pro-German activities of the fascist Lapua movement contributed to the growing tensions.

In Finland, the civil war and the mutual terror between "Reds" and "Whites" had left a deep division in society. Only in the 1930s, especially after the election of Kyösti Kallio as president in 1937, did a policy of reconciliation begin to take hold in the country. In the same year, the Social Democratic Party of Finland, under Prime Minister Aimo Kaarlo Cajander, became involved in government for the first time since the Civil War. The former "white general" Mannerheim also campaigned for overcoming the rifts. On the anniversary of the end of the Civil War in May 1933, he declared:

"A patriotic spirit, the expression of which is the will to defend, and a determination to stand in line like a man if this country should ever have to be defended, that is all we ask, and we need ask no more who was where in each case fifteen years ago."

The initial situation from the perspective of the Soviet Union

From the Soviet Union's point of view, the relationship with Finland in 1939 was strained and characterized by mistrust. Economic relations between the two countries were minimal despite the long common border, and the Soviet government took great offence at the repression of Finnish communists. Inspired by the Greater Finland ideology, thousands of Finnish volunteers had actively fought against Soviet Russia in several theaters of war between 1918 and 1922. Thus, numerous Finnish volunteers intervened in the Estonian War of Independence and elsewhere undertook three military expeditions into Soviet Russian Karelia, some of which took months to put down. Furthermore, Finnish volunteers supported separatist uprisings in East Karelia and Nordingermanland. With Nordingermanland, pro-Finnish separatists had controlled an area a short distance from Leningrad for a few months in 1920. The Soviet Union therefore considered the city to be in immediate danger in the event of the outbreak of war. Moreover, in the late 1930s under Stalin, irredentist and revisionist tendencies increased sharply, aimed at regaining territory lost to the Russian Empire after 1918.

Since the mid-1930s, the Soviet leadership was convinced by the resurgence of Japan and the rise of Hitler in Germany of the coming of a new war between the great powers. The military and political leadership of the Soviet Union saw the Baltic States and Finland as strategically important. The Gulf of Finland and the coast of the Baltic States were seen as a potential gateway for foreign powers to the second largest city, Leningrad. Likewise, Stalin was convinced that any coastal fortifications of Finland and the Baltic states could severely limit the Soviet Baltic Fleet's ability to act in the Baltic Sea in the event of war. In the event of a land war, the Soviet Union leadership saw the Baltic States as a necessary thoroughfare for the deployment of its forces against potential adversaries in Central Europe and the Finnish part of Karelia as a possible deployment area for foreign powers against Leningrad. Likewise, Stalin suspected Finland as a possible base for air strikes by a foreign power against Soviet territory.

Until the conclusion of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact in August 1939 and its execution in the invasion of Poland, the Soviet leadership tried to realize the neutralization of the strategically important area through non-aggression pacts with the neighboring states, including Finland. However, the breakup of Poland as a state had changed the balance in Eastern Europe. Stalin now sought to incorporate Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania into the Soviet Union's defense system through alliances and the stationing of Soviet troops. The small neighbours agreed to these alliances in the autumn of 1939 after brief negotiations accompanied by military threats.

Negotiations with Finland and the start of the war

On September 11, 1939, the Soviet Union began a new round of negotiations with Finland. Stalin based his demands on the imminent danger of war and the need to secure Leningrad through strategic reorganizations. To this end, Finland was to cede the southern part of the fortified Karelian Isthmus in exchange for other Karelian territories. The future Finnish-Soviet border was to be advanced to within about thirty kilometers of the city of Wiborg (Viipuri), Finland's second largest city. This would have meant the abandonment of all Finnish defenses along the so-called Mannerheim Line. Similarly, Stalin demanded the lease of the Hankoniemi peninsula around the city of Hanko, the cession of islands in the Gulf of Finland, and the Fishermen's Peninsula on the coast of the Northern Arctic Ocean. As compensation, the Soviet Union offered Finland the cession of territories in Karelia about twice as large in area. The Finnish government, under Prime Minister Cajander, was initially divided over accepting the Soviet demands, but ultimately rejected them. As a concession, the Finnish government offered the Soviet Union the cession of the area around the village of Terijoki, which was rejected by the Soviet Union as quite insufficient. Finland then initiated a partial mobilization of the army and unsuccessfully attempted to ally with Sweden. A request for diplomatic assistance to Germany was also unsuccessful. Negotiations continued until 13 November without an agreement being reached.

Since Finnish intelligence indicated that the Red Army was not ready for action, Finnish Foreign Minister Eljas Erkko assumed that the Soviet Union would not start a war. The government's assessment that parliament would not agree to any territorial cessions also contributed to Finland's negative attitude.

The Soviet side, however, had already envisaged a military option before the end of the negotiations. On November 3, 1939, Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov insinuated in Pravda that Finland had belligerent intentions towards the Soviet state. On the same day, the Baltic Fleet received orders to go on standby and draw up final plans for an invasion of Finland. Stalin ordered the same to the Leningrad Military District of the Red Army on November 15. On November 26, the Red Army staged a border incident in the village of Mainila (Russian Майнило) in which Soviet troops were allegedly fired upon by Finnish artillery (Mainila Incident). When the Finnish government denied these allegations, Molotov severed relations with Finland and terminated the existing non-aggression pact. Without the Soviet Union making a formal declaration of war, the Red Army crossed the border in the early morning of November 30, 1939. That afternoon, President Kallio formally declared that the country was in a state of war. Cajander's government, whose assessment of the threat of war had proved inaccurate, resigned that same evening; it was succeeded the following day by a new government on a broader parliamentary basis under Risto Ryti, formerly head of the Bank of Finland.

Finnish Defence

At the beginning of the war, the Finnish army was not only outnumbered because of its small population, but also poorly prepared for the war in material terms. In the years leading up to the war, the military and political leaderships had been in constant dispute over what the former saw as a completely inadequate military budget. In particular, the two strongest parties, the anti-militarist Social Democrats and the austerity-minded Landbund, blocked an increase in armaments spending, even in the face of the worsening international situation. As late as August 1939, Prime Minister Cajander, presiding over a coalition of both parties, expressed his pleasure that Finland had used its funds for more useful things instead of rapidly obsolete war material. The government also favored the nascent domestic defense industry over foreign manufacturers. This, in addition to the lack of money, slowed down the modernization of the armed forces' stocks.

At the beginning of the war, the Finnish army numbered 250,000 soldiers, 130,000 of whom defended the Karelian Isthmus and 120,000 the rest of the eastern border. Due to the lack of weapons, however, the actual operational strength was reduced by 50,000. Heavy armament was even scarcer. For example, the Finnish army had only thirty tanks at its disposal, and they had only been in service for a few weeks. There was also a shortage of automatic weapons. The whole army possessed a total of only one hundred anti-tank guns, imported from Sweden. The soldiers therefore often had to resort to improvised solutions for anti-tank purposes, such as throwing incendiary devices made from bottles, to which they gave the name Molotov cocktail. The artillery in many units dated back to World War I times and had a short range. There were only 36 guns per division; there was also a shortage of artillery ammunition. The Finnish air force comprised only one hundred aircraft. No anti-aircraft guns (Flak) could be issued to the combat troops themselves, as the available one hundred were used for defending cities against bombing raids.

In the pre-war period, the Finnish High Command had regarded the Soviet Union as the only realistic enemy of the war. Therefore, the Karelian Isthmus had been fortified by what the press later called the Mannerheim Line. There the command under Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, who had taken over the command of the army again in 1939, saw the decisive front of the war, since here the fastest way to Viipuri and Helsinki led into the Finnish heartland. The line, built since the 1920s, consisted of about a hundred concrete bunkers. However, they were often structurally weak; only the newest ones were made of solid reinforced concrete. The bunkers were densest in the area around Summa, which was, for one thing, dangerously close to Viipuri and where, moreover, the treeless heath land favoured tank attack. In addition, the line was reinforced by field fortifications laid out by the troops. Already in peace the border was shielded by four covering groups. Mannerheim further reinforced it by five divisions, divided into the army's 2nd and 3rd Corps. In total, the commander at the isthmus, Hugo Österman, had about 92,000 soldiers under his command.

There was also enough infrastructure on the northern shore of Lake Ladoga to allow an offensive by a modern army. To defend this flank of the Mannerheim Line, the Finns posted the 4th Corps there under Woldemar Hägglund. The 4th Corps had at its disposal two divisions with a total of about 28,000 soldiers. According to the assessment of the Finnish High Command, the remaining part of the border with the USSR, which was about a thousand kilometers long, was impassable for an army due to dense forestation and lack of roads. Therefore, only improvised smaller formations were deployed there, which were to block the few transport axes. This group of Northern Finland was under the command of General Viljo Tuompo. Mannerheim himself, as commander-in-chief of the army, kept two divisions in reserve.

Soviet invasion plan

During the ongoing negotiations, Stalin instructed the Chief of the General Staff of the Red Army, Shaposhnikov, to draw up a plan for the invasion of Finland. Shaposhnikov outlined an operation lasting several months, which would have required a large part of the army. This Stalin rejected and delegated the work to the commander of the Leningrad Military District, Merezkov. This general held out the prospect of an operation lasting only a few weeks and, as far as land forces were concerned, involving only the troops of the Leningrad Military Administrative Region.

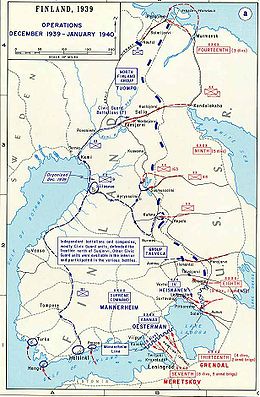

Merezkov's plan focused on the Karelian Isthmus and thus on the Mannerheim Line. This eye of a needle represented the shortest route to the Finnish capital Helsinki. Furthermore, the road and railway connections there were the best developed. The 7th Army under Vsevolod Yakovlev was to break directly through the Finnish fortification line with the help of 200,000 soldiers and 1,500 tanks. The 8th Army under Khabarov was to bypass the Finnish fortifications north of Lake Ladoga and stab the defenders of the line in the back. To this end, 130,000 troops and 400 tanks were available. Further north, two other armies were to launch attacks on the almost uninhabited border of the two countries, barely served by roads, to cut off communications and tie up Finnish troops. To this end, the 9th Army under Duchanov stood north of the Soviet 8th Army. It represented the link to the 14th Army under Frolov, which was to advance to Petsamo. The two armies on this secondary front had a total of 140,000 men and 150 tanks at their disposal. Their goal was the occupation of the entire Finnish territory.

The Baltic Fleet was to fulfil several missions in this plan. Submarines were to keep watch on neighboring countries and cut off Finland's sea links. Marines were to capture the small islands in the Gulf of Finland; naval aviators were to support land forces on the main front. In addition, a Soviet fleet force of three battleships was to provide artillery support to the ground forces on Lake Ladoga. Overall, the Red Army had a superiority in soldiers of three to one, in artillery of five to one, and in tanks of eighty to one.

Signing of the Finnish-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact on 21 January 1932 by the Finnish Foreign Minister Aarno Yrjö-Koskinen (left) and the Soviet Ambassador in Helsinki Ivan Maiski

The Mannerheim Line was the main line of defence of the Finns on the Karelian Isthmus.

Return of the Finnish negotiating delegation from Moscow on 16 October 1939, with the head of the delegation Juho Kusti Paasikivi second from the left.

Reviews

In the historiography, the Winter War has experienced two completely contradictory assessments. In the Soviet Union and its allied states, Soviet action was seen as a legitimate exercise of geostrategic interests and a safeguarding of Leningrad's strategic military position. Leningrad, which lay only 50 kilometres from the old Finnish border, had been defenceless against an attack from Finnish soil. Finland had been under the influence of both the Western powers and Nazi German imperialism and would therefore have constituted an important deployment area in the event of war against the Soviet Union. According to this assessment, the war could have been avoided through reasonable concessions by the Finnish government. Finnish historians with pro-Soviet attitudes have also subscribed to this assessment in the postwar period.

Finnish and Western historians, on the other hand, consider the Soviet Union's attack to be the expression of Stalin's and Molotov's imperialist policy. According to this view, a concession in the negotiations of autumn 1939 would have decisively weakened Finland's position and exposed the country to new dangers. Here, particular reference is made to the fact that, after the war had begun, Stalin demonstrably initially pursued the goal of the complete occupation of Finland.

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Winter War?

A: The Winter War was a conflict fought between the Soviet Union and Finland from November 1939 to March 1940.

Q: Why did the Soviet Union try to invade Finland?

A: The Soviet Union tried to invade Finland soon after the Invasion of Poland.

Q: Why did the Soviet military forces expect a victory over Finland in a few weeks?

A: The Soviet army had many more tanks and planes than the Finnish army.

Q: Why did the Finnish forces resist better and longer than expected?

A: The Finnish forces had good winter clothes, wore white coats which camouflaged them in the snow, and they moved around on skis, which made it easy for them to sneak up on the Soviet soldiers.

Q: Why did the Soviet army not do well in the Winter War?

A: The Soviet army did not have good winter clothes, and they wore dark green coats, which made them easy to see in the snow.

Q: What percentage of their country did the defeated Finns have to give up?

A: The defeated Finns had to give up 11% of their country.

Q: Did Finland try to get their lost land back?

A: Yes, Finland tried to get their lost land back in the Continuation War.

Search within the encyclopedia