Wilhelm Busch

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Wilhelm Busch (disambiguation).

Heinrich Christian Wilhelm Busch (* 15 April 1832 in Wiedensahl; † 9 January 1908 in Mechtshausen) was one of Germany's most influential humorous poets and illustrators. In addition, he was active as a painter influenced by Dutch masters.

His first picture stories appeared from 1859 as broadsides. They were first published in book form in 1864 under the title "Bilderpossen". Already famous throughout Germany from the 1870s onwards, at his death he was considered a "classic of German humour" thanks to his extremely popular picture stories. As a pioneer of comics, he created Max und Moritz, Fipps, der Affe, Die fromme Helene, Plisch und Plum, Hans Huckebein, der Unglücksrabe, the Knopp trilogy and other works that are still popular today. He often satirized the characteristics of certain types or social groups, such as the complacency and double standards of the philistine or the sanctimoniousness of clergymen and laymen. Many of his two-liners have become established German idioms, e.g. "Vater werden ist nicht schwer, Vater sein dagegen sehr" (Becoming a father is not difficult, but being a father is") or "Dieses war der ersten Streich, doch der zweite folgt sogleich" (This was the first prank, but the second follows immediately).

Wilhelm Busch was a serious and withdrawn man who lived many years of his life in seclusion in the provinces. He himself attached little value to his picture stories and referred to them as "Schosen" (French chose = thing, quelque chose = something, anything). At the beginning he regarded them only as a means of earning a living, with which he was able to improve his oppressive economic situation after abandoning his art studies and years of financial dependence on his parents. His attempt to establish himself as a serious painter failed by his own standards. Wilhelm Busch destroyed most of his paintings; those that survive often seem like improvisations or fleeting notes of color and are difficult to assign to a painterly direction. His poetry and prose poetry, influenced by the style of Heinrich Heine and the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, met with incomprehension from the public, who associated his name with comic picture stories. The fact that his artistic hopes were disappointed and that he had to withdraw exaggerated expectations of himself, he sublimated with humour. This is reflected in his picture stories as well as in his literary work.

.jpg)

Wilhelm Busch before 1908

Poetry, Writing, Drawing

Creative periods

Busch's biographer Joseph Kraus divides Wilhelm Busch's work into three creative periods. He points out, however, that this is a simplification, since works also appear in each of these periods that, by their nature, fall into a later or earlier period. All three creative periods have in common Busch's fixation on forms of German petty-bourgeois life. His peasant figures are persons devoid of any sensitivity, and even his last prose sketch shows village life in unsentimental drasticness.

The years 1858 to 1865 are the years in which Wilhelm Busch worked primarily for the Fliegende Blätter and the Münchener Bilderbogen. The creative period from 1866 to 1884 is characterized primarily by the great picture stories such as the pious Helene. Busch's picture stories are the opposite of the culture of representation that characterized the Gründerzeit. They are life stories in a descending line, such as that of the painter Klecksel, who begins as a hopeful son of the Muses and ends as a mildewed landlord. Other stories are about children and animals that promise nothing good, or they are farces that ridicule what seems great and important to themselves. The early picture stories seem to follow the pattern of the children's books of classical Enlightenment education, of which Heinrich Hoffmann's Struwwelpeter is one of the best-known examples. This children's literature aimed to demonstrate to children the "devastating consequences of evil behavior." The pedagogical quintessence of Busch's picture stories, however, is often no more than an empty form or philistine banality, and takes the morally beneficial application ad absurdum. Wilhelm Busch attached no artistic value to the picture stories that made him a wealthy man: "I regard my things for what they are, as Nuremberg trumpery, as whistles whose value is to be sought not in their artistic content but in the demand of the public ..." he wrote in a letter to Heinrich Richter.

From 1885 until 1908, the year of his death, Wilhelm Busch's work is dominated by prose and poetry. Der Schmetterling, a prose text published in 1895, is generally understood as an autobiographical account. Peter's enchantment by the witch Lucinde, whose slave he describes himself as, may be an allusion to Johanna Keßler. And like Peter, Wilhelm Busch returns to the place of his birth. It corresponds to the pattern of the Romantic travel narrative as established by Ludwig Tieck with Franz Sternbald's Wanderungen, and Wilhelm Busch plays virtuously with the traditional forms, motifs, images and topoi of this narrative form.

Technology

The publisher Kaspar Braun, who commissioned Wilhelm Busch with the first illustrations, had founded the first workshop in Germany to work with wood engraving when he was young. This method of letterpress printing had been developed towards the end of the 18th century by the English graphic artist Thomas Bewick and became the most widely used reproduction technique for illustrations in the course of the 19th century. Wilhelm Busch always emphasized that he first made the drawings and then the verses to go with them. Surviving preparatory drawings show line notes, pictorial ideas, and studies of movement and physiognomy close together. Busch then transferred the preliminary drawings with the aid of a pencil onto primed slabs of end-grain or heartwood made from hardwoods. The work was difficult because not only the quality of one's own transfer affected the result, but also the quality of the wooden printing block. Each scene of the picture story corresponded to a designated boxwood block. Everything that was to remain white on the later print was engraved from the plate by skilled workers with burins. Wood engraving allows a finer differentiation than woodcut, and the possible tonal values almost approach intaglio processes such as copperplate engraving. However, the wood engraver's execution was not always adequate to the preliminary drawing, and Wilhelm Busch had individual plates reworked or even newly produced. The graphic technique of wood engraving, for all its possibilities, did not allow for fine lines. This is the reason why, especially in the picture stories up to the mid-1870s, the contours of Busch's drawings come so strongly to the fore, which gives Busch's figures a specific characteristic.

From the mid-1870s, Wilhelm Busch's drawings were printed using zincography. With this technique, there was no longer any danger of a wood engraver changing the character of his drawings. The originals were photographed and transferred to a light-sensitive zinc plate. This process still required a clear ink stroke, but it was much faster, and the picture stories, beginning with Herr und Frau Knopp, have more the character of a free pen and ink drawing.

Language

Wilhelm Busch's drawings are heightened in their effect by the unerring verses. Characteristic of the picture story are humorous surprises and linguistic daring, e.g. rhymes that use hyphenation in unexpected ways such as the well-known "Everyone knows what such a May/beetle is for a bird." In addition, there are ironic twists, mockeries of romantic stylistic elements, exaggerations, and double entendres. Accordingly, a number of humorous poets refer to Wilhelm Busch as their spiritual ancestor or at least relative. This applies to Erich Kästner, Kurt Tucholsky, Joachim Ringelnatz, Christian Morgenstern, Eugen Roth and Heinz Erhardt. The contrast between the comic drawing and the seemingly serious accompanying text, which is so typical of Busch's later picture stories, can already be found in Max und Moritz. Thus the maudlin grandeur of the widow Bolte bears no relation to the actual occasion, the loss of her chickens:

Out of my eye flow my tears!

All my hoping, all my longing,

My life's most beautiful dream

Hanging from this apple tree

Many of the two-liners that have passed into common usage have the appearance of a weighty wisdom saying, but on closer examination turn out to be a sham truth, a sham morality or even just a truism. Characteristic of his work are also countless onomatopoeias. "Schnupdiwup" Max and Moritz kidnap the roasted chickens with a fishing rod through the chimney, "Ritzeratze" they saw a gap in the "bridge", "Rickeracke! Rickeracke! Geht die Mühle mit Geknacke", and "Klingelings" Kater Munzel tears the chandelier from the ceiling in the pious Helene. Wilhelm Busch is similarly inventive in assigning proper names that often aptly characterize his characters. "Studiosus Döppe" would surprise the reader as a spiritual greatness; characters like the "Sauerbrots" do not lead one to expect cheerfulness, and "Förster Knarrtje" no elegant saloon lion.

The greater part of the picture stories is written in four-legged trochaic verse:

Max and Moritz, these two

Didn't like him for it.

An overweighting of the stressed syllables intensifies the comedy of the verses. In addition, there are dactyls in which a stressed syllable is followed by two unstressed syllables. They are found, for example, in Plisch and Plum and underline the lecturing, solemn address that teacher Bokelmann gives to his pupils, or build up tension in the Sauerbrot chapter of Abenteuer eines Junggesellen through the alternation of trochaic and dactylic syllables. The fact that Busch often matches the form and content of his poetry is also evident in Fipps, der Affe, where epic hexameter is chosen for a conversation about the wisdom of creation culminating in the dignity of man.

In his picture stories as well as in his poems, Wilhelm Busch occasionally used fables that were familiar to the reader, sometimes stripping them of their morals in order to make use of the comic situations and constellations that develop from the fable events, and sometimes making them the medium of a completely different truth. Here, too, Busch's pessimistic view of the world and of humanity comes to the fore. While traditional fables convey the value of a practical philosophy that distinguishes between good and evil, in Busch's worldview good and evil actions merge seamlessly.

Humor

Wilhelm Busch's humour is difficult to describe and often goes as far as the caricaturistic, the grotesque and even the macabre. Busch expresses himself not only in the verses accompanying the pictures in his picture stories, but also in his poems and in the unpictured introductory texts to his picture stories. The main effect is apparently based on a combination of the familiar, the "unfortunately all too true" etc. with the unexpected, the surprising and a certain irony (also self-irony) and cruelty (see below). For example, Wilhelm Busch was unmarried all his life and, as a follower of Schopenhauer's "pessimism", was a subtle connoisseur of philosophy, which he nevertheless turned into the popularly humorous. In the introduction to Abenteuer eines Junggesellen he writes:

Socrates, the old man,

spoke very often in great sorrow:

"Oh how much is hidden,

what you still don't know."

And so it is.

there's one thing you can't forget:

There's one thing we do know down here,

namely, if one is dissatisfied

This is also Tobias Knopp,

and he's upset about it.

(Before the last two lines a picture of the "annoyed" Knopp.)

For the grotesque of Busch's humor the following text:

At the thought

so divorcing

into an unburied grave

he squeezes off a tear.

She lies where he sat

appropriate to his pain.

(Before the last two lines a picture with an oversized tear in front of a normal-sized bench).

An example of the subtle cruelty of his humour - although here it is not a matter of physical but of psychological cruelty to begin with - is the poem interpreted by, for example, Erich Ponto - the interpretation is archived by Deutsche Grammophon - Die erste alte Tante sprach .... In it three old aunts discuss a birthday present for "Sophiechen". The second old aunt suggests a pea-green dress, because Sophiechen would not (!) like it. The poem continues:

The third aunt was fine with that,

"Yes," she spoke, "with yellow tendrils.

I know she's not upset,

and has to say thank you, too."

The poem Sie war ein Blümlein also bears witness to the subtle cruelty:

She was a flower pretty and fine,

Brightly blooming in the sunshine.

He was a young butterfly,

Who hung blissfully on the flower.

Often came a little bee with buzzing

And nibbles and purrs around there.

Often a beetle crawled tickling crawling

Up and down the pretty little flower.

Oh, God, how this has hurt the butterfly.

So painfully through the soul went.

But what horrifies him most,

The very worst came last.

An old donkey ate the whole

Plant so beloved by him.

Corporal punishments and other cruelties

In most of Wilhelm Busch's picture stories, people are beaten, tormented, injured and beaten: sharp pencils pierce painters' models, housewives fall into kitchen knives, thieves are impaled by umbrellas, tailors decapitate their tormentors with scissors, rascals are ground into grain in mills, drunks are charred into a blackish something, and cats, dogs and monkeys lose their extremities. Impalement injuries are common. Today, Wilhelm Busch is therefore classified by some pedagogues and psychologists as a sadist in disguise. Eva Weissweiler also points out that Wilhelm Busch's tail is so frequently burned, torn off, pinched, stretched or eaten that it can hardly be considered a coincidence. She believes that these aggressions are not directed against animals, but against the phallic symbolism of the animal's tail, and should be seen against the background of Wilhelm Busch's underdeveloped sexual life. Drastic texts and images were, however, quite characteristic of caricatures of the time, and neither publishers nor the public nor censors found anything remarkable in them. The theme and motifs of Busch's early picture stories in particular were often taken from the trivial literature of the 18th and 19th centuries, and Wilhelm Busch often even toned down the gruesome outcome of his originals considerably.

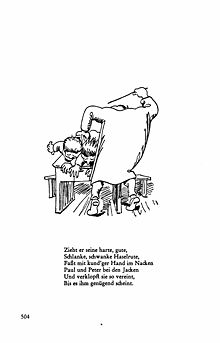

It is similar with corporal punishment, which was one of the common and widely accepted means of education in the 19th century (and beyond). Wilhelm Busch, with Meister Druff in Abenteuer eines Junggesellen and with Lehrer Bokelmann in Plisch und Plum, caricatured an almost sexual pleasure in this punishment. Beatings and humiliations as the basic framework of a pedagogy are also described in the late work, so that the Busch biographer Gudrun Schury describes these means of education as one of Busch's life themes. Even in the poetry collection Zu guter Letzt from 1904, which consists of 100 poems, it says:

The rod swishes and the cane whirs.

You can't show what you are

What a pity, O man, that good things should come to thee

Basically so repugnant.

Although there is a note in Busch's estate entitled "Durch die Kinderjahre hindurchgeprügelt" (Beaten through the childhood years), there is no indication that Wilhelm Busch referred to himself in this short note. It cannot refer to his father and uncle, since Busch only mentions a beating he received from his father, and his uncle Georg Kleine also only punished his nephew once with beatings after he had stuffed the village idiot's pipe with cow hair. Georg Kleine, however, used a dried dahlia stem instead of the usual peddigree, so that the punishment had a more symbolic character. Eva Weissweiler points out, however, that Busch attended the Wiedensahl village school for three years, where it is highly likely that he not only witnessed corporal punishment, but was probably physically chastised himself. In Abenteuer eines Junggesellen (Adventures of a Bachelor), Wilhelm Busch outlines a form of non-violent reform pedagogy that fails just as much as the beating method depicted in the following scene. The beating scenes ultimately express Wilhelm Busch's pessimistic view of man, rooted in 19th-century Protestant ethics influenced by Augustine: man is evil by nature, he will never master his vices. Civilization is the goal of education, but it can only superficially cover up the instinctive in man. Gentleness only leads to a continuation of his misdeeds and punishment must be, even if this leads to incorrigible rascals, trained puppets or in extreme cases to dead children. Whether in Busch's case there was also a desire for punishment turned outward must be left open.

Anti-Semitism accusation

The so-called Gründerkrach of 1873 led to a growing criticism of high finance, combined with a spread and radicalization of modern anti-Semitism, which became a strong undercurrent in German opinions and attitudes in the 1880s. Anti-Semitic agitators such as Theodor Fritsch distinguished between "rapacious" finance capital and "creative" production capital, between the "good," "down-to-earth" "German" factory owners and the "rapacious," "greedy," "bloodsucking" "Jewish" finance capitalists, who were called "plutocrats" and "usurers.

Wilhelm Busch is also accused of having used these anti-Semitic clichés. Two passages are usually cited as evidence for this. In the pious Helene it says:

And the Jud with a crooked heel,

Crooked nose and crooked pants

Meanders to the high stock exchange

Deeply depraved and soulless.

The poet and Busch admirer Robert Gernhardt points out that this passage, read in context, does not reflect Busch's own view, but caricatures that of the villagers among whom Helene lives. For in the rest of the passage, Busch, who is liberal, anti-clerical, and not averse to alcohol, paints other alleged dangers of city life in ironically black colors:

I don't want to talk about restaurants,

Where the evil one brags nightly,

Where in the circle of liberals

One hates the Holy Father.

Just as ironically, Busch caricatures the rural counter-image as a false idyll:

Come to the country where gentle sheep

And the pious lambs are.

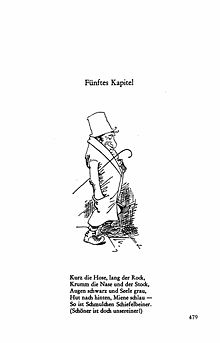

The second, even more explicit caricature of "the Jew" is found in the story Plisch und Plum:

Short the pants, long the skirt

Crooked the nose and the stick

Eyes black and soul gray,

Hat back, face smart -

So is Schmulchen Schiefelbeiner

(We're more beautiful than you and me.)

In the opinion of Busch biographer Joseph Kraus, these verses could also have been written in an anti-Semitic diatribe. Biographer Eva Weissweiler sees in them one of the most memorable and ugly portraits of an East Jew that the German satirical landscape has to offer.

But even here the context, especially the ironic last verse of the quoted passage - "Schöner ist doch unsereiner!" - that Busch by no means regarded the gentiles as the nobler sort of people. Robert Gernhardt points out how exceedingly rare it is to find caricatures of Jews in Busch's work. Apart from the ones mentioned, there is only one other drawing in the Fliegende Blätter of 1860, which, moreover, illustrated the text of another author. In Gernhardt's view, Wilhelm Busch's Jewish figures are nothing more than stereotypes such as the limited Bavarian peasant or the Prussian tourist.

Joseph Kraus also shares this view: Wilhelm Busch had turned against cunning profiteers in general and used caricatures of Jews, but not only of them, for this purpose in some picture stories. This can be seen in a two-liner from the picture story Die Haarbeutel. According to it, profit-seeking fellow human beings are

Mainly Jews, women, Christians,

That trick you terribly.

Erik de Smedt speaks of a "certain ambivalent attitude of Busch towards the Jews". In Eduard's Dream, for example, he puts the following sentence into the mouth of the title character: "Business is flourishing, and so is the Israelite. He is as clever as anything, and where there is something to be earned, he leaves nothing out ..." In contrast, the preceding passage about the house and tenants of an "anti-Semitic building contractor" speaks of vices of all kinds, e.g. attempted murder, envy, hatred, fraud and marital strife. Busch's prejudices are again evident where Eduard encounters the signs of the zodiac:

Not far from there, in his shop, sat the clever, crooked-nosed "water man" - Jews are everywhere! - and regulated the "scales" in his favor.

Joseph Kraus believes that Busch - like most of his contemporaries - perceived Jews as foreign bodies and shared some of their anti-Semitic thought patterns. However, this did not preclude close friendships with Jews, for example with the conductor Hermann Levi.

Picture stories as an anticipation of modern comics

Busch's work contributed to the development of comics; Andreas C. Knigge calls him the first virtuoso of picture narration. His work has therefore increasingly earned him the honorific epithet "grandfather of comics" or "forefather of comics" from the second half of the 20th century onwards.

Even his early picture stories differ from those of his colleagues who also worked for Kaspar Braun. His pictures show an increasing concentration on the main characters, are more sparing in their internal drawing and less detailed in their ambience. The punch line develops out of a dramaturgical understanding of the whole narrative. All picture stories follow a plot that begins with a description of the circumstances from which the conflict arises, then increases the conflict and finally brings it to a resolution. The plot is broken down into individual situations, as in a film. In this way, Busch conveys the impression of movement and action, sometimes reinforced by changes of perspective. In the opinion of Gert Ueding, the depiction of movement that Busch achieves despite the limitations of the medium has so far remained unrivalled.

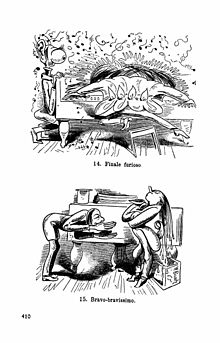

One of Busch's most ingenious and revolutionary picture stories is The Virtuoso, the story of a pianist who gives a private concert to an enthusiastic audience on New Year's Day, published in 1865. This satire on the self-promoting attitude of artists and their exaggerated worship deviates from Busch's pattern of other picture stories because the individual scenes are not annotated with bound texts, but only terms from musical terminology such as introduzione, maestoso or fortissimo vivacissimo are used. The scenes increase in tempo, with every part of the body and every garment included in this increase. Finally, the penultimate scenes become a simultaneous show of several phases of movement by the pianist, and the notes dissolve into note signs dancing above the grand piano. Visual artists have drawn inspiration from this pictorial story well into the 20th century. In a letter to his gallerist Herwarth Walden, August Macke even stated that he considered the term Futurism for the avant-garde art movement that arose in Italy at the beginning of the 20th century to be inappropriate, since Wilhelm Busch had already been a Futurist who had captured time and movement in the picture.

Similarly forward-looking are individual scenes in the pictures for the Jobsiade, published in 1872. At Jobs' theological examination twelve clerical gentlemen in white wigs sit opposite him. To their by no means difficult questions their examinee answers so stupidly that each answer triggers a synchronous shaking of the examiners' heads. The wigs start to move indignantly, and the scene becomes a study in movement reminiscent of Eadweard Muybridge's phase photographs. Although Muybridge had begun his motion studies in 1872, he did not publish them until 1893, so this fluid transition from drawing to cinematography is also one of Busch's pioneering artistic achievements.

Moritziaden

The greatest long-term success, both internationally and in the German-speaking world, was Max und Moritz: In the year of Busch's death, there were already English, Danish, Hebrew, Japanese, Latin, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Hungarian, Swedish and Walloon translations of his story. However, there were also countries where the "Elaborat" was resisted for a long time. As late as 1929, the Styrian school board forbade the sale of Max und Moritz to young people under the age of eighteen. In 1997, however, there were at least 281 translations into dialects and languages, including languages such as South Jutish.

Very early on, there were so-called moritziads, that is, picture stories that followed Busch's original very closely in their plot and narrative style. Some, like the Tootle and Bootle story published in England in 1896, took so many literal translations from the original that they were actually a kind of pirated print. By contrast, the Katzenjammer Kids by Holstein-born Rudolph Dirks, which appeared every Saturday from 1897 in a supplement to the New York Journal, are considered a genuine neologism, modeled on Max and Moritz. They were created at the suggestion of publisher William Randolph Hearst with the explicit desire to invent a brother and sister following the basic pattern of Max and Moritz. The Katzenjammer Kids are considered one of the oldest comic strips and still continue.

The German-speaking world has a particularly rich tradition of Moritziads: This ranges from Lies and Lene; the sisters of Max and Moritz from 1896 to Schlumperfritz and Schlamperfranz (1922), Sigismund and Waldemar, des Max und Moritz Zwillingspaar (1932) and Mac and Mufti (1987). Whereas in the original Max and Moritz expose as a hypocritical façade the bravado and blandness of their adversaries, who enforce their authority by force, the Moritziads often merely reflect the spirit of their respective eras. In both World War I and World War II there are Moritziades recounting the fate of the protagonists in the trenches, the Winterhilfswerk collected money with their badge, in 1958 the CDU in North Rhine-Westphalia fought for votes in the election campaign with the help of Max-und-Moritz figures, in the same year the GDR satirical magazine Eulenspiegel caricatured moonlighting, and in 1969 Wilhelm Busch's heroes were involved in the student movement.

Final image from Diogenes and the bad boys of Corinth

_014.png)

Single scene from Max and Moritz

Two scenes from Fipps the Monkey

Single Scene from Plisch and Plum

Introduction to the 5th chapter of Plisch and Plum

Scene 12 and 13 from The Virtuoso

Scene 14 and 15 from The Virtuoso

Katzenjammer Kids: Single scene of a comic from 1901 by Rudolph Dirks

Painting

Wilhelm Busch seems never to have completely lost the self-doubt about his painterly abilities that befell him when he first came to grips with the old Dutch painters in Antwerp during his lifetime. Few of his paintings he felt were finished. He often piled them on top of each other in corners of his studio while they were still damp, so that they stuck together indissolubly. If the piles of paintings became too high, he burned them in the garden. Of the surviving paintings, only a few are dated, so it is difficult to place them in any historical order. His doubts about his painting abilities are also expressed in his choice of materials. In most of his works, his painting grounds are chosen uncharitably. Occasionally they are uneven cardboard or only makeshiftly smoothed spruce boards secured with only one burr strip. One exception is a portrait of his patroness Johanna Keßler, which is painted on canvas and, at 63 by 53 centimetres, is one of Wilhelm Busch's largest pictures. Most of his paintings have a much smaller format. Even the landscapes are miniatures, whose reproductions in illustrated books are often larger than the respective original. Since Wilhelm Busch used not only cheap painting grounds, but also cheap colors, many of his paintings are now heavily darkened and thus have an almost monochrome effect.

Many of his pictures show a fixation on rural life in Wiedensahl or Lüthorst. Depicted are motifs such as pollarded willows, crofts in cornfields, cowherds, autumn landscapes, meadows with streams. The so-called red-jacket pictures are striking. Among Wilhelm Busch's nearly 1000 paintings and sketches, there are about 280 in which a red jacket can be seen. Usually it is a tiny figure seen from behind, dressed in muted colours but wearing a bright red jacket. The portraits usually show typical village characters.

One exception, in addition to portraits of the Keßler family, is a series of portraits of Lina Weißenborn created in the mid-1870s. The 10-year-old girl was the daughter of one of the Jewish families that had been resident in Lüthorst for generations. They show a serious girl with dark oriental features who hardly seems to notice the painter. Her portraits are considered by some critics to be among Wilhelm Busch's most poignant portraits, going far beyond the typecasting of his other portraits.

The influence of Dutch painting is unmistakable in Busch's work. "Hals verdünnt und verkleinert ... aber etwas Hals eben doch", wrote Paul Klee after visiting a Wilhelm Busch memorial exhibition in 1908. Of particular influence on the painterly work of Wilhelm Busch is Adriaen Brouwer, who exclusively thematized scenes from peasant and tavern life, peasant dances, card players, smokers, drinkers and thugs. Busch avoided a discussion with influential German painters of his time such as Adolf Menzel, Arnold Böcklin, Wilhelm Leibl or Anselm Feuerbach. The discovery of light in early Impressionism, new colors such as aniline yellow, or the use of photographs as aids were not taken into account in his painting. His landscapes from the mid-1880s, however, show the same coarse brushwork that was characteristic of paintings by the young Franz von Lenbach. Although he was friends with several painters of the Munich School and an exhibition of his paintings would have been possible without any problems due to these contacts, he never took this opportunity to present his painterly work. Only towards the end of his life did he publicly exhibit a single painting.

Wilhelm Busch Rural parlour with Epiphany blessing 1877

Portrait of a Boy, ca. 1875, Hamburg Kunsthalle

Forest Landscape with Hay Hay and Cows , c. 1884/1893

Questions and Answers

Q: Who was Wilhelm Busch?

A: Wilhelm Busch was a German painter and poet.

Q: What was Wilhelm Busch known for?

A: Wilhelm Busch was known for his satirical picture stories.

Q: Where was Wilhelm Busch born and when did he die?

A: Wilhelm Busch was born on April 15, 1832 in Wiedensahl, near Hannover, and he died on January 9, 1908 in Mechtshausen.

Q: What did Wilhelm Busch study before becoming a caricature artist?

A: Wilhelm Busch studied mechanical engineering before studying art in Düsseldorf, Antwerp, and Munich.

Q: How did Wilhelm Busch start his career as a caricature artist?

A: Wilhelm Busch started his career as a caricature artist by drawing caricatures.

Q: Did Wilhelm Busch write poems in addition to creating picture stories?

A: Yes, Wilhelm Busch wrote a number of poems in a style similar to his picture stories.

Q: Were Wilhelm Busch's oil paintings sold during his lifetime?

A: No, Wilhelm Busch's more than 1,000 oil paintings were not sold until after his death in 1908.

Search within the encyclopedia