Wars of the Roses

![]()

This article is about the English succession struggles in the 15th century. For other meanings, see War of the Roses.

·

The White Rose of the House of York

·

The red rose of the house of Lancaster

The Wars of the Roses are the intermittent battles between the two rival English noble houses of York and Lancaster from 1455 to 1485. The noble houses were different branches of the House of Plantagenet and traced their lineage back to King Edward III, from which they derived their claim to the English royal crown: The Lancasters had ascended to the throne in 1399, but the House of York considered itself passed over. When King Henry VI of the House of Lancaster fell into mental derangement, this eventually triggered open civil war. The conflicts took a very high toll of blood among the British nobility and, among other things, ended the male lines of these two houses.

The wars initially produced victory for the House of York, which secured kingship for Edward IV at the Battle of Towton in 1461 and 1461-1470 and 1471-1483. An intervening Lancasterian return to power in 1470 ended in 1471 with Edward IV's final victory at the Battle of Tewkesbury and the extinction of the Lancaster male line. After Edward's death in 1483, however, the wars ultimately did end in 1485 with a victory for the Lancaster party over the House of York at the Battle of Bosworth, in which Richard III, the last king from the House of Plantagenet, met his death. Henry Tudor, the pretender to the Lancaster throne only remotely connected with the royal house through his mother, was then crowned king as Henry VII, and through his marriage to Elizabeth of York united the two houses in the House of Tudor. A final Yorkist revolt, in which the impostor Lambert Simnel posed as Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick, was put down at the Battle of Stoke in 1487. The real Edward was imprisoned by Henry VII and beheaded in 1499. Thus the male line of the House of York was also extinguished.

The coats of arms of the two opposing families contained roses (a red rose for Lancaster, a white rose for York), so that the term "Wars of the Roses" later became established for this conflict. However, the assignment of the roses with the respective houses can only be proven to a limited extent in the contemporary sources.

Picking the Red and White Roses , 1910, fresco by Henry Paine, scene from William Shakespeare's drama Henry VI. , part 1

Previous story

See also: Family tree of the houses Lancaster and York

The root cause of the conflict lay as early as 1399, but only came to light in 1455. In 1399, the English Parliament deposed King Richard II and appointed his cousin Henry as the new king. Henry founded the House of Lancaster after conquering England in a victorious campaign. Richard II was the son of Edward, Prince of Wales, called "The Black Prince." The latter was the eldest of the five sons of Edward III, the now crowned Henry IV being the son of the third eldest son, John, Duke of Lancaster. Edward III's second eldest son, Lionel, Duke of Clarence, had left no direct heir, but his daughter's grandson, Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, was considered heir to his claim to the throne. However, as the latter was only eight years old in 1399, far too young to become king, he was passed over. Henry IV had him arrested and imprisoned in an Irish fortress.

In 1413 his successor Henry V brought Mortimer back to his court, and the latter was content to recognise Henry's rule. When Mortimer's brother-in-law Richard, Earl of Cambridge, initiated a conspiracy against Henry V in 1415 and proposed Edmund Mortimer as his successor, the latter notified the king instead, and Cambridge was executed as a high traitor. After Mortimer's death in 1425, however, his claim to the throne passed to the son of Cambridge and his sister Anne Mortimer, Richard, Duke of York, who was also descended through his father in a direct male line from Edmund, Duke of York, the fourth eldest son of Edward III.

Henry VI Lancaster, the son of the king who died in 1422, had ascended the throne at the age of only seven. Various parties were formed at his court which attempted to influence the king. Richard of York joined the party of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester and uncle of the king, of which he became leader after Gloucester's death in 1447. As Duke of York, Earl of March, and Earl of Cambridge, he was the most powerful vassal of Henry VI. When England lost the Hundred Years' War against France in 1453 and the king sank into mental derangement in response, York, among numerous others, was able to use this power vacuum to increase his power. He rallied around him the numerous opposition to Henry VI, who personally blamed the latter for the lost war. This defeat made Henry VI an incompetent ruler in their eyes - not a misjudgment in parts at all, since Henry VI had already shown little drive before the onset of his mental illness and was responsible for the loss of English territories in France. Richard of York's main opponent was Edmund Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset, who together with Henry's wife Margaret of Anjou ran the affairs of state for the ailing king. This was also about money: as long as Somerset's party remained the court party, Richard faced financial ruin, for the king was in debt to both. He could ultimately pay one only by exploiting the other. York was in a precarious position; Somerset had to be removed.

However, the evaluation of this prehistory and the entire war is problematic due to the fact that the ultimately victorious Tudors were descended from the House of Lancaster. The House of York, their opponent in the war, they marked in their historiography accordingly negative.

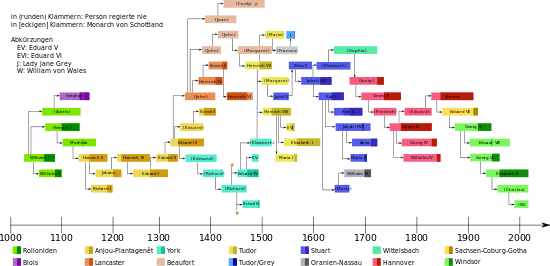

Simplified chronological and kinship table of the English monarchs since William the Conqueror, colour-coded by dynasties.

War History

Outbreak of the war and first years of war

Battles of the Wars of the Roses (1455-1485)

St Albans - Blore Heath - Ludlow - Northampton - Wakefield - Mortimer's Cross - St Albans - Ferrybridge - Towton - Hedgeley Moor - Hexham - Edgecote Moor - Losecote Field - Barnet - Tewkesbury - Bosworth Field - Stoke

The year 1453 was marked by several decisive events: In addition to the aforementioned end of the Hundred Years' War and Henry VI's subsequent nervous breakdown, there was the birth of Edward, heir to the throne, on 13 October and Somerset's imprisonment in November. As a result of the king's continuing mental illness, Richard of York was appointed Lord Protector in March 1454.

This prompted the Lancastrian party around Queen Margaret to act. York was forced to resign his office in 1455 and retreated to his lands in the north. A Great Council was called for 21 May 1455 at Leicester in central England. York meanwhile gathered troops with which he marched on London and attacked his opponents at St Albans north of London on 22 May. The First Battle of St Albans ended in a complete victory for York, who was able to eliminate many of his opponents, including Somerset and the Earl of Northumberland, and who took control of the king and restored him to his former offices. His most important ally in this became Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, who went down in history as the "kingmaker" and was related to the House of York through his wife Cecily Neville. The years up to 1459 were marked by political power struggles between Richard of York, now Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and Queen Margaret.

In 1459 hostilities between the parties broke out again. A Yorkist victory at Blore Heath in September was followed by the defeat of Ludlow, after which their army effectively disbanded. Richard of York fled to Ireland with his second eldest son Edmund, Earl of Rutland, and his eldest son Edward, Earl of March, with Warwick to Calais, where Warwick was the commander of the troops there. When the two returned to England with the troops from Calais the following year, they succeeded in recapturing the king at the Battle of Northampton on 10 July 1460, again killing many Lancastrian leaders. York then returned to London in October and entered Parliament, which had been summoned at short notice, under the royal banner. However, Richard's expectations of immediate kingship were not fulfilled, but in the Act of Accord of 25 October he had himself declared King Henry's successor, thus disinheriting his son Edward. To disperse the remaining Lancastrian forces, which had retreated north under the leadership of Queen Margaret and Henry Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, the son and heir of Edmund Beaufort, the Duke of York and his troops also moved there. But Henry Beaufort lay in wait for him at Wakefield. In the ensuing engagement Richard fell, as did his brother-in-law Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury, and his son Edmund, Earl of Rutland.

Richard's eldest son Edward then took over the leadership of the House of York. From Wales, Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke and King Henry's half-brother, attempted to bring reinforcements to Queen Margaret, but he was defeated by Edward at the Battle of Mortimer's Cross in early February 1461. When Lancastrian forces then won a victory against the Yorkists under Warwick's leadership at St Albans, in which King Henry was also freed from captivity, the city of London denied Margaret of Anjou and her army entry, and they were forced to flee north. On 29 March 1461, Edward, with Warwick's help, defeated the queen's army led by Somerset at the Battle of Towton, considered one of England's bloodiest - of the 80,000 or so soldiers on both sides, 20,000 to 30,000 died. When he was crowned Edward IV of England on 28 June and Henry VI and his wife subsequently fled to Scotland, the first phase of the Wars of the Roses came to an end and the kingship of the House of York began.

Only in the north near the Scottish border the Lancastrian troops still resisted. In 1462 Henry Beaufort made a mock reconciliation with Edward IV and was made Duke of Somerset again by the latter, but the attempt failed, Somerset returned to the Lancastrians after a year and a half and fell at the Battle of Hexham in May 1464.

Shifting coalitions

In the years that followed, there was an estrangement between Edward IV and his most important ally, his cousin Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick. The reason for this was that Warwick had been working incessantly to find a French bride for the king and to persuade him to enter into an alliance with France, while the latter was secretly marrying Elizabeth Woodville, a widowed ex-Lancastrian. Other factors also played a part, for example King Edward was more keen to form an alliance with Burgundy, France's arch-enemy, and listened to William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, whom Warwick hated for this. He also detested the Queen's now powerful family, who had been enfeoffed with numerous titles of nobility by Edward IV.

In 1469 it finally came to a break and Richard Neville started a rebellion against the king. He allied himself with his brother George, Duke of Clarence, to whom he gave his daughter Isabel in marriage and whom he wanted to see on the throne instead of Edward IV. He succeeded in eliminating parts of the hated Woodville family, had the Earl of Pembroke executed, and even captured the king and imprisoned him at Warwick Castle. However, when Edward IV was freed by his brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, their forces defeated Warwick's rebels, and Richard Neville gradually became isolated, he fled by ship to Calais. But when the crew, of which he was still commander, would not let him go ashore, he suddenly allied himself with Queen Margaret, who had found asylum in France, and the House of Lancaster. The marriage of Warwick's daughter Anne to Edward, heir to the House of Lancaster, sealed the alliance of the former enemies. In mid-1470 the Earl of Warwick led a Lancastrian army into England, expelled Edward IV without having fought a battle, and restored to power Henry VI, who had been imprisoned in the Tower of London for the past several years. Edward IV fled to the Netherlands to join his brother-in-law Charles, Duke of Burgundy.

King Henry VI was incapable of ruling because he was mentally deranged. The affairs of state were therefore carried out by Warwick and a council of crown chosen by him, but because of this several of his allies increasingly distrusted him. When Edward IV landed at Ravenspur with Burgundian troops in March 1471, the Earl of Northumberland, a Lancastrian, defected to him. At Easter he was able to place the Lancastrian superior force near St Albans and defeat them at the Battle of Barnet. Richard Neville fell in this battle. Thereupon Queen Margaret and her son, who had remained in France to the last, landed in England, rallied the scattered troops about them, and proceeded to Wales, whence they hoped to obtain support. But before reaching the frontier Edward IV. caught them up, and beat them devastatingly at the battle of Tewkesbury. Crown Prince Edward perished, but in what way is disputed. When Henry VI was also murdered in the Tower of London shortly afterwards, the direct line of the House of Lancaster was extinguished.

The last living Lancastrian pretender to the throne, Henry Tudor was taken by his uncle Jasper to Brittany in France after Edward IV's reassumption of the throne, where he staked his claim from exile for the next few years. This he derived from his mother Margaret (Edward had also inherited his kingship through a wife), who was a great-granddaughter of John, Duke of Lancaster, son of King Edward III and progenitor of the House of Lancaster. This made her a 2nd cousin of King Henry and, with the House of Lancaster all but extinct, the only one who could pass on the claim to her son.

The End of the House of York

In the following years, Edward IV was able to rule unchallenged and brought new prosperity to England. When he died at Easter 1483, he left the throne to his eldest son, Edward, but he was only 12 years old. After his uncle Richard, Duke of Gloucester, had won the power struggle with the family of the queen dowager Elizabeth Woodville for the guardianship of the little king and had his opponents executed, he brought his nephew together with his younger brother Richard to the Tower of London to prepare the king for his coronation. In June Gloucester suddenly had William Hastings, his brother's chief confidant and his former ally, executed for allegedly plotting against him. Shortly afterwards Parliament declared him the sole legitimate heir to the throne of Edward IV, and his coronation as Richard III took place on 6 July 1483. This action was justified a few months later by the document Titulus Regius, in which Richard's brother's children were shown to be illegitimate. The two princes in the Tower, the legitimate heirs, disappeared without trace in the following period. As some of the lords began to think Richard the murderer of the princes, they fell away from him and defected to Henry Tudor in France. This opposition to Richard, however, was greatly embellished by the historians of the Tudor period.

In the autumn of 1483 a revolt under the Duke of Buckingham, in which Tudor took part, failed. When defections from England became more numerous two years later, Tudor crossed into England again, landing at Milford Haven in Wales. On his march through England his force continued to grow, and on August 22, 1485, with the help of his stepfather Thomas Stanley, who stabbed the king in the back at the crucial moment, he defeated Richard III, who was slain fighting, at the Battle of Bosworth Field.

Tudor succeeded him as Henry VII, married the eldest daughter of Edward IV, Elizabeth of York, and thus united the two noble houses of Lancaster and York in the House of Tudor. This is generally regarded as the end of the bitterly fought Wars of the Roses and the beginning of an era of peace. Henry VII, however, had to hold his own against both real and false Yorkist pretenders thereafter, so that some historians date the end of the Wars of the Roses a few years later. In 1487, for example, Lambert Simnel impersonated Edward, Earl of Warwick, the nephew of Edward IV and Richard III, and crossed into England with a mercenary army from Ireland, a stronghold of the House of York. He gained the support there of John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, whom Richard III had designated as his heir to the throne. King Henry VII defeated the latter's army at the Battle of Stoke, north of Nottingham, on 16 June 1487. Simnel was taken prisoner and Lincoln fell. In the 1490s Perkin Warbeck acted as pretender.

Questions and Answers

Q: What were the Wars of the Roses?

A: The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487) were a series of civil wars fought over the throne of England between supporters of the House of Lancaster, the Lancastrians, and supporters of the House of York, the Yorkists.

Q: What was King Henry VI seen as by many people?

A: King Henry VI was seen as a poor ruler by many people because he lacked interest in politics and suffered from mental illness.

Q: What caused the wars to begin?

A: The wars began for several reasons including England's defeat in the Hundred Years' War in France, money problems after that war, and issues with feudalism.

Q: How did they get their name?

A: The name "Wars of the Roses" was first used only in 19th century and comes from white rose symbol for House of York and red rose symbol for House of Lancaster.

Q: What symbols were used during this time?

A: During this time most soldiers fought under symbol their local nobleman rather than either house's symbol; however, after it ended red rose became associated with House Lancaster while white rose became associated with House York.

Q: Where did these houses originate from?

A: Both houses originated from Plantagenet royal house through King Edward III.

Q: Which cities are these houses named after?

A: The Houses are named after cities Lancaster and York but neither city played big role during war as both owned land all over England and Wales.

Search within the encyclopedia