War of the Pacific

![]()

This article is about the war on the Pacific coast of South America from 1879 to 1884. For the 1969 Chilean feature film, see The Saltpetre War.

![]()

This article needs a revision: multiple grammar and semantic errors, unclear sentences, incorrectly formatted evidence.

Please help improve it, and then remove this marker.

Saltpetre War

The Saltpetre War (also Pacific War, Spanish Guerra del Pacífico) was fought between Chile on the one hand and Peru and Bolivia on the other over the territories Región de Arica y Parinacota, Región de Tarapacá and Región de Atacama, in what is now northern Chile, in the years from 1879 to 1883 (between Chile and Peru) and until 1884 (between Chile and Bolivia).

In February 1878, the Bolivian government under Hilarión Daza (who had come to power in a coup in 1876) imposed a new export tax on Chilean saltpetre companies in violation of the 1874 frontier treaty, which expressly forbade the increase of existing or imposition of new taxes on these Chilean companies for 25 years.

The Government of Chile filed a complaint and offered to submit the matter to neutral arbitration. The government of Bolivia considered the matter to be a purely Bolivian one and proposed instead to resolve the dispute in Bolivian courts. The Chilean government declared that the collection of the new tax meant the end of the frontier treaty and that Chile therefore no longer considered itself bound by the frontier treaty and would renew its legal claims to the territory. On February 6, 1879, Bolivia cancelled the license of the Chilean company Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarril de Antofagasta (CSFA) and confiscated its property. When an attempt was made to auction it off on February 14, 1879, 200 Chilean soldiers landed in Antofagasta and took possession of the majority Chilean-inhabited region.

Peru offered its mediation, but at the same time rearmed its army and navy and mobilized. Chile initially accepted Peru's mediation. Under Chilean pressure, Peru was forced to admit a bilateral connection with Bolivia via a secret treaty since 1873. Chile then demanded a declaration of neutrality from Peru in late March 1879, which Peru refused to discuss until a parliamentary session a month later. On April 5, Chile declared war on the Peru-Bolivia alliance.

After six months of war, Chile was able to gain naval supremacy, thus isolating the coastal zones of the Atacama Desert, which at the time were only accessible by sea. President Daza was deposed on 28 December 1879 and went into exile in France.

As late as 1879, Chile occupied the Tarapaca region on Bolivia's southern border with Chile, and in mid-1880 the region around Tacna and Arica in the north of the disputed territory. In 1880 Bolivia withdrew from the war. In January 1881 Lima, the capital of Peru, fell. The war changed to guerrilla warfare and lasted until October 1883. A new government under Miguel Iglesias opened negotiations with Chile and signed the Treaty of Ancon on October 20, 1883. Three days later, Chilean troops withdrew from Lima. By June 1884, they had retreated behind the Río Sama.

The final borders with Bolivia were established in the Peace Treaty of 1904. The treaty (Spanish Tratado de Paz y Amistad entre Chile y Bolivia) was signed on October 20, 1904. Bolivia surrendered Tarapaca in exchange for the right to use the port of Arica via a new railway line. Chile built the railway line between La Paz and Arica, which Bolivia was entitled to use free of charge. In the final peace treaties, the cities of Tacna were given to Peru and Arica to Chile.

Burying bodies after the battle of Tacna

Previous story

Contested borders after independence

Alto Perú, as Bolivia was called during its colonial period, was initially part of the Viceroyalty of Peru. According to a decree of the Spanish crown, it only had access to the sea via Arica, which was Peruvian at the time. In 1776, Spain transferred Alto Perú's territorial dependence to the newly created Viceroyalty of La Plata, later Argentina. Alto Perú thus officially lost any claim to access to the Pacific, as Spain divided the viceroyalties by oceans, meaning there was a Viceroyalty of Peru on the Pacific and a Viceroyalty of La Plata on the Atlantic.

After the end of Spanish colonial rule in South America between 1810 and 1830, the course of the borders between the new states was unclear in many regions, and conflicts were the result. The affiliation of the Atacama region on the Pacific coast between the newly formed states of Chile (founded in 1818), Peru (founded in 1821) and Bolivia (founded in 1825) was also disputed. The doctrine Uti possidetis provided for the adoption of the old boundaries of the Spanish colonies. Contrary to this doctrine, Bolivia, since the declaration of independence in 1825, claimed the largely uninhabited desert region as part of its national territory and founded the port city of Cobija there in 1830, which was tolerated by Chile. Chile, however, continued to consider the region, 95% of which was populated by Chileans, as its territory.

The Border Treaty between Bolivia and Chile of 1866

In the border treaty of 1866, Chile and Bolivia agreed on 24° south latitude as the north-south border and the "watershed line" as the east-west border. The zone between 23° and 25° south latitude became the "Common Profit Zone" (Zona de beneficios mutuos). Taxes from the extraction of minerals from this zone were to be shared equally between Chile and Bolivia. This agreement turned out to be difficult to implement, as differences soon arose over the terms "minerals", over the zoning of the rich silver mines of Caracoles, and over Bolivia's difficulties in remitting 50% of the tax collected to Chile.

In 1873, both governments sought a solution and the Corral-Lindsay Protocol was negotiated to resolve the known disagreements. This agreement was ratified by Chile, but the Bolivian parliament, under Peruvian pressure, refused to approve it.

The secret alliance treaty between Peru and Bolivia of 1873 and the position of Argentina

In view of the growing influence of Chilean companies and further Chilean immigration to Bolivia and Antofagasta, Peru saw its supremacy in the South Pacific threatened and formed a secret alliance with Bolivia with the aim of using military force to force Chile to revise its borders in favor of Peru and Bolivia.

The treaty also provided for the inclusion of Argentina in the alliance. In 1873, the Argentine lower house approved the project and granted 6,000,000 pesos in additional funds for the War Ministry. However, due to territorial disputes with Bolivia over Tarija and Chaco, the three states were ultimately unable to agree on joint action, so the Argentine Senate did not sign the agreement. Argentina rejected a war effort for the militarily weak Bolivia, and Peru did not want to risk a war with Chile over Patagonia.

In 1875 and 1878, as tensions increased between Chile and Argentina over territorial disputes over Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, and the Straits of Magellan, Argentina attempted to join the alliance, but in the meantime Peru refused. At the start of the war in 1879, Peru and Bolivia offered Argentina the Chilean territories between 24° and 27° south latitude in exchange for joining their alliance, but Argentina refused due to the weakness of its navy.

The Border Treaty between Bolivia and Chile of 1874

Bolivia changed its policy in 1874 and reached agreement with Chile on a new border treaty. The region north of the 24th parallel south was to continue to belong to Bolivia and the joint economic zone was to be dissolved on condition that Bolivia was not allowed to increase the export tax on Chilean companies now based in its territory for a period of 25 years.

The Peruvian saltpetre monopoly

Peru mined guano in the Tarapacá region and financed large parts of its state budget with it since the 1840s. In the 1860s, however, state revenues fell as a result of low quality and quantity of guano exports. At the same time, interest in the region grew when extensive deposits of nitrate (saltpeter) were found there during these years. This raw material was valuable and necessary for the production of fertilizer and explosives (until the Haber-Bosch process became operational in 1913). Because of increasing trade in saltpetre on the world market, Peru had considerable difficulty selling its guano from 1877 onwards; more than 650,000 tons were eventually stored in the ports.

To compensate for the decline in guano exports, the Peruvian government attempted to establish a state monopoly over the extraction and trade of saltpetre from 1873 onwards. In 1875, Peru nationalized all the salitreras (saltpetre factories), thus ensuring the state direct control over production in its own country. But there were also nitrate deposits further south, in Antofagasta off the then Chilean border. From 1876, the Peruvian state had the straw man Henry Meiggs buy licences to extract saltpetre in Chile.

The Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarriles de Antofagasta

The Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarriles de Antofagasta (CSFA for short) was a Chilean joint stock company based in Valparaíso. CSFA had received a license from the Bolivian government under José Mariano Melgarejo to mine nitrates in Antofagasta. This first license was revoked after a coup and, after negotiations between the CSFA and the new Bolivian government, was granted again tax-free for 15 years on December 27, 1873. At the time, it was disputed whether this new license grant required parliamentary approval. This left the CSFA as the only saltpetre producer not under the control of the Peruvian state.

The British company Antony Gibbs & Sons had a minority shareholding of 34 % in the CSFA and was the only seller of Peruvian saltpetre in Europe at the time. The government in Lima urged the Gibbs company to put pressure on the Chilean management of the CSFA to cut production. Henry Gibbs warned CSFA that maintaining current production levels would cause problems with Peru and Bolivia, which saw this as a violation of their interests.

The 10 centavos tax

|

|

|

| Miguel Iglesias, later president of Peru. His son Alejandro fell in the battle of Miraflores. | Juan José Latorre took part in the shelling of El Callao, where his brother Elías Latorre defended the fortress. |

To finance the state treasury, the Bolivian government decided in 1878 under President Hilarión Daza to impose a special tax of 10 centavos on every hundredweight of saltpetre mined, thus violating the Treaty of 1874. Chile lodged a protest against this breach of the treaty. Bolivia then initially refrained from levying the tax, but did not withdraw the law. In February 1878, due to a financial emergency following a drought year and lack of funds to repair earthquake damage, Bolivia decided to collect the tax from the profitable saltpetre industry CSFA retroactively from 1874. After CSFA refused to pay the tax, citing the treaty, in January 1879 Bolivia expropriated the premises owned by CSFA and offered them for sale. Chile considered this an open breach and nullification of the 1874 treaty and sent troops to the city of Antofagasta, originally founded by Chileans (Juan López and José Santos Ossa).

Conclusion: Causes of the war

Ronald Bruce St. John says in The Bolivia-Chile-Peru Dispute in the Atacama Desert:

Even though the 1873 treaty and the imposition of the 10 centavos tax proved to be the casus belli, there were deeper, more fundamental reasons for the outbreak of hostilities in 1879. On the one hand, there was the power, prestige, and relative stability of Chile compared to the economic deterioration and political discontinuity which characterised both Peru and Bolivia after independence. On the other, there was the ongoing competition for economical and political hegemony in the region, complicated by a deep antipathy between Peru and Chile. In this milieu, the vagueness of the boundaries between the three states, coupled with the discovery of valuable guano and nitrate deposits in the disputed territories, combined to produce a diplomatic conundrum of insurmountable proportions.

"While the treaty of 1873 and the imposition of the 10-centavos tax were the casus belli, there were deeper and more significant reasons for the outbreak of war in 1879. On the one hand, Chile's power, prestige, and relative stability in contrast to the economic decline and political instability in Peru and Bolivia after independence. On the other hand, political and economic domination of the region was at stake. Moreover, there was a deep antipathy between Peru and Chile. Under these conditions, the unclear borders between the three states, together with the discovery of valuable guano and nitrate deposits in the disputed territories, resulted in an insoluble conflict."

The US-American historian William F. Sater names the following reasons for the war:

- Chilean interests in the production sites in the region and the plan to usurp them by occupying the territory in question to compensate for the loss of export revenues. Many of CSFA's shareholders were members of the Chilean government and exerted massive pressure on President Anibal Pinto, influencing public opinion to adopt a more confrontational political course towards Bolivia. Sater adds, however, that parts of the Chilean business elite had also made extensive investments in Bolivia and were therefore opposed to an escalation of the conflict because they feared the possible loss of their property in Bolivia.

- Peru and Chile's geopolitical interests in the South Pacific. Both Peru and Chile tried to get Bolivia on their side with the promise of a cheaper export port. Since the actual Bolivian export port was in Arica and not Antofagasta, Peru ultimately offered more favorable terms. At the same time, Chile offered Bolivia to occupy the Peruvian territories of Tacna and Arica and then hand them over to Bolivia.

- Peru's economic interests in a monopoly on saltpetre extraction to compensate for its reduced revenues from guano mining. Peru made an unsuccessful attempt to control the saltpetre trade through a state monopoly as early as 1873 and nationalised the saltpetre industry in 1875. In 1876, Peru began to acquire Bolivian licenses for the mining of nitrates, and the government put pressure on the British firm Antonny Gibbs & Sons to curb CSFA's saltpetre production.

- The compulsion resulting from domestic and public pressure on governments - both in Chile and Peru - to be intransigent in the dispute over the region, and the fear of the governments of both countries - in case of hesitation - to be overthrown by a coup.

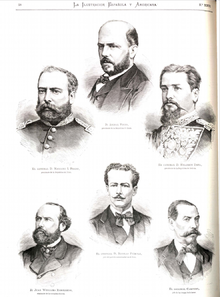

Political and military leaders of the three countries at the beginning of the war, from left to right: the three presidents Mariano Ignacio Prado (Peru), Aníbal Pinto (Chile), and Hilarión Daza (Bolivia), the Chilean fleet commander Juan Williams Rebolledo, the Peruvian party leader Nicolás Piérola, and the Bolivian commander-in-chief and later president Narciso Campero (contemporary illustration, published on 15 July 1879)

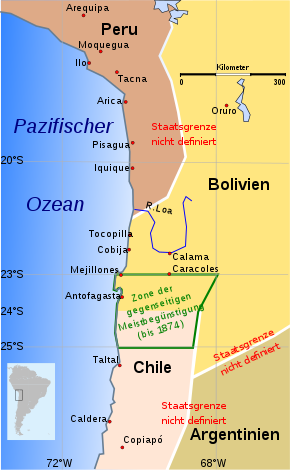

Distribution of territory before the war. Bolivia then had wide access to the sea in the disputed area. The 24th parallel was the north-south border with Chile, and the "zone of mutual most-favoured-nation" (outlined in green) was dissolved in 1874. Argentina's border areas were also disputed: the Puna de Atacama and eastern Tarija.

Start of the war

Antofagasta occupation

Chilean units occupied the port city of Antofagasta on February 14, 1879, the day the auction of the company was to take place. Since only five percent of the population was Bolivian, there was no resistance. On February 22, 1879, Peru sent a group of diplomats, led by José Antonio de Lavalle, to Chile to mediate between Bolivia and Chile and find a peaceful solution. Meanwhile, Peru mobilized its armed forces. On February 27, the Bolivian parliament authorized the government to declare war, but it was not initially issued.

Declarations of War

On March 1, Bolivian President Hilarión Daza ordered by decree various measures, including a ban on trade and communication with Chile "as long as the state of war continues" and the departure of all Chileans within ten days (except in cases of serious illness or disability). Chilean mining companies were allowed to maintain operations under the supervision of a government overseer. The embargo measures were to be temporary unless hostile actions by the Chilean military "require a vigorous counterstrike by Bolivia." Although Daza spoke of a "state of war," a formal declaration of war had not yet been made. On March 4, the Peruvian legation under de Lavalle arrived in Valparaíso.

At an international meeting in Lima on 14 March, Bolivia declared that it was in a state of war with Chile. This was intended to make it more difficult for Chile to continue to procure arms abroad. Peru's mediation efforts in Chile were thus undermined. That same day, Chilean Foreign Minister Alejandro Fierro sent a telegram to Chile's ambassador in Lima, Joaquin Godoy, seeking an immediate declaration of neutrality from Peru. On March 17, Godoy personally presented the Chilean request to Peruvian President Prado. The Peruvian government wanted to wait for the decision of the parliament.

Bolivia, in turn, asked Peru to recognize the case of alliance that Chile had caused. When the Peruvian mediator de Lavalle was officially and directly asked in Chile whether Peru and Bolivia maintained a secret defensive alliance and whether Peru intended to recognize the case of alliance, he could no longer evade and answered both questions in the affirmative. Chile then declared war on Peru and Bolivia on April 5, 1879. On April 6, Peru proclaimed the case of alliance and declared war on Chile.

Search within the encyclopedia