Voltaire

![]()

This article explains the writer and philosopher. For other meanings, see Voltaire (disambiguation).

Voltaire [vɔltɛːʀ] (actually François-Marie Arouet [fʀɑ̃swa maʀi aʀwɛ], born 21 November 1694 in Paris; † 30 May 1778 ibid) was a French philosopher and writer. He is one of the most widely read and influential authors of the Enlightenment.

Especially in France, the 18th century is also called "the century of Voltaire" (le siècle de Voltaire). As a lyricist, dramatist and epic poet, he wrote primarily for the French educated bourgeoisie, and as a narrator and philosopher for the entire European upper class in the Age of Enlightenment, whose members usually had a command of the French language and read French-language works in part in the original. Many of his works went through several editions in rapid succession and were often promptly translated into other European languages. Voltaire had an excellent knowledge of English and Italian, and published some texts in them as well. He spent a considerable part of his life outside France and knew the Netherlands, England, Germany and Switzerland from his own experience.

With his critique of the ills of absolutism and feudal rule, as well as the ideological monopoly of the Catholic Church, Voltaire was a thought leader of the Enlightenment and an important pioneer of the French Revolution. In presenting and defending what he believed to be right, he showed extensive knowledge and empathy with the ideas of his contemporary readers. His precise and universally understandable style, his often sarcastic wit, and his art of irony are often considered unsurpassed.

François-Marie Arouet (Voltaire), Portrait by Nicolas de Largillière (painted after 1724/1725)

Signature of Voltaire

Effect and positions

Voltaire was not a system-building thinker, but a "philosophe" in the French sense, that is, an author who wrote fiction as well as philosophical, historical, and scientific writings, and who was active in publishing.

His philosophical tales (contes philosophiques), written from around 1746 onwards, were the most enduring and ultimately the most widespread, in which he brought central ideas of the Enlightenment to a wider audience in an undogmatic and entertaining way.

He probably considered himself primarily an important dramatist on the basis of his more than fifty stage plays, some of which were very successful. In particular, the tragedy Zaïre (1736) was also performed with great resonance in Italy, Holland, England and Germany (in 1810 in Weimar by Goethe); it belonged to the fixed repertoire of the Théâtre français for more than 200 years. It was also recognized by contemporaries as a worthy successor to the great tragedians Corneille and Racine. Goethe translated the tragedies Mahomet and Tancrède.

Voltaire had a groundbreaking effect as the founder of a historiography oriented towards cultural history. Scientifically ambitious and written in a way that was easy to understand, his historiographical works opened up a tradition that is still alive in France today. The use of lower case in French writing also goes back to him. He was the first to practice it consistently in his Siècle de Louis XIV. The inscription on Voltaire's sarcophagus in the Panthéon (see above), which was presumably formulated by a member of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres in 1791 and approved by the latter, visibly attempts to present the three main sides of his work as roughly equally weighted: fiction, historiography, philosophy.

Social Criticism

Voltaire fought for equality of all citizens before the law, not equality of status and property. He believed that there would always be rich and poor. As a form of government, he favored monarchy, at the head of which he wanted a "good king." He believed to see such a king in Frederick II, until the disagreement.

The quote "I disapprove of what you say, but would defend to the death your right to say it" is often mistakenly attributed to Voltaire. In fact, the phrase comes from S. G. Tallentyre, but she had used it to characterize only one of Voltaire's attitudes and had not provided a citation.

Slavery and serfdom

Voltaire's opinions on blacks, slaves, and the slave trade have been controversial in research. Claudine Hunting, for example, believes that Voltaire decisively rejected slavery. However, Christopher L. Miller and Michèle Duchet, for example, point to contrary findings. It has been wrongly claimed, especially by tendentious authors, that Voltaire directly enriched himself from the overseas slave trade. In 1877, Eugène de Mirecourt had published excerpts from a letter to this effect - which, according to recent research, is probably not authentic or has been forged. In fact, however, Voltaire had invested in the Compagnie des Indes Orientales, which, among other things, participated in colonial wars of conquest and for a time held the monopoly on the slave trade in France. He seems to have regarded the employment of servants worse than the slave trade, which he must have regarded as a necessary evil. Voltaire took the naming of a slave trader's ship after him as an honor. He described an African albino brought to Paris by a slave trader as one "of the animals which resemble men." It seems to him to approximate the missing link between man and animal, which Voltaire had also thematized elsewhere. Voltaire considered blacks to be a species of humans distinct from whites, within which it would be seriously debated whether they themselves were descended from apes or vice versa.

In Voltaire's Essai sur les mœurs et l'esprit des Nations we find the passage: "We buy the house slaves exclusively from the negroes; this trade is held against us. A people who trade with their children is even more condemnable than the buyer. This trade shows our superiority; he who gives himself a master was born to have a [master]." Already the editor Condorcet, an opponent of slavery, commented that this passage in no way contained a defense of slavery. The older secondary literature has not consistently followed this explanation. The work also contains the thesis of a natural and rarely changing gradation of genius and character among nations, which justifies why Negroes are slaves of other people. But Voltaire also describes there the unworthy treatment of slaves, "men like ourselves," and compares the disregard for Jews in ancient Rome with "our" view of "Negroes" as "underdeveloped species of men."

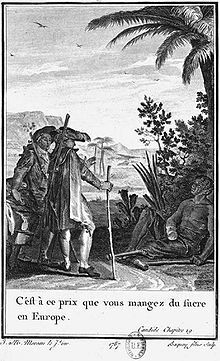

Voltaire also made some decidedly critical statements about slavery. Thus under the keyword "Esclaves" in the Questions sur l'Encyclopédie of 1771. He also impressively describes the mutilations of the slave of Surinam in Candide, which is illustrated in the Kehl edition by an engraving by Jean-Michel Moreau. In Commentaire sur l'Esprit des lois (1777), Voltaire praises Montesquieu for condemning slavery. Voltaire enthusiastically commented on the attitude of the Quakers in Pennsylvania, who advocated and also enforced an abolition of slavery. He called the war of Spartacus just, if not the only just war. In the last years of his life, Voltaire, together with the jurist friend Charles-Frédéric-Gabriel Christin, campaigned for an end to serfdom in the Jura, where the right of the dead hand had survived. In French law, the term mainmorte included the person of the serf. Voltaire did not achieve his goal; the serfs of Franche-Comte were not freed until 1790 in the ensuing French Revolution.

Church Criticism

Voltaire was one of the most important church critics of the 18th century. This earned him the early disapproval of the Roman Catholic Church, which branded him an atheist and banned his writings.

The builder of a chapel in Ferney with the inscription Deo erexit Voltaire, 1761 ("Built for God by Voltaire"), however, always defended himself against the accusation of atheism. For all his distance from the traditional religions, he held an attitude akin to the deist position, that is, a tolerant and undogmatic monotheism freed from archaic ideas. Thus he deduced from the regularity of the cosmos the existence of a supreme intelligence (Traité de métaphysique, 1735) and emphasized the moral usefulness of belief in God: "If God did not exist, one would have to invent him" (in Épitre à l'auteur du livre des trois imposteurs, 1770). Without any dogmatic pretensions, Voltaire also affirmed the immortality of the soul and the freedom of the will.

He was extremely critical of the Roman Catholic Church and its entanglement with secular power. He concluded many of his later letters with the famous slogan Écrasez l'infâme! (literally, "Crush the infamous!"), usually referring to the church as an institution. According to another reading, l'infâme meant superstition (l'infâme superstition), which Voltaire often castigated. In 1768, under the pseudonym Corbera, he published the pamphlet Epître aux Romains, which calls for resistance against the Pope.

Voltaire wished to be buried in church, but on his deathbed he refused communion and last rites, as well as the retraction of his writings demanded by the church. Nor did he back down from his denial of Jesus' sonship with God.

Thus he wrote to Frederick II: Quote: "I have an insurmountable aversion to the way in which one...in our Roman - Catholic...religion concludes one's life. It seems to me most ridiculous to be oiled as one departs for that other world, something like the way one lubricates the wheel axles of one's paddy wagon when it goes on a great journey. This nonsense...disgusts me so much..."

He was a member of the Masonic lodge Les Neuf Sœurs, founded in 1776.

statements about Judaism

The traditions and commandments of the monotheistic religions, in Voltaire's view, are in complete opposition to the ideals and goals of the Enlightenment, tolerance and rationalism. In particular, he saw in the mythological roots of Judaism the typical embodiment of legalism, primitivism and blind obedience to traditions and superstitions and, in addition to the defense of Jews, there is a sometimes fierce rejection of Judaism. In Voltaire's 118-article philosophical dictionary Dictionaire philosophique, the Jews are attacked in several articles, including being called "the most detestable people on earth."

"I speak with regret of the Jews: that nation is, in many respects, the most contemptible that ever polluted the earth."

- Voltaire: Dictionnaire philosophique

Voltaire derided the Pentateuch in particular as a barbaric aberration and values based on it as a "cultural embarrassment" with historical irrelevance. An article on the Jews accordingly concludes the first part as follows:

"You will meet in them only an ignorant and barbarous people, who have long combined the filthiest avarice with the most detestable superstition, and the most unconquerable hatred of all the peoples whom they tolerate and enrich themselves with. Let them not, however, be burned."

- Voltaire: Dictionnaire philosophique

In 1762, the Portuguese Jew Isaac de Pinto wrote a rejoinder to these tirades of Voltaire, which correspond to well-known anti-Jewish positions and points of view. This rejoinder was reprinted several times and received greater attention in the years that followed. In a letter of reply, Voltaire admitted to having been "cruel and unjust" on many occasions and announced that he would correct these errors. At the same time, however, he reaffirmed his rejection of Jewish laws, books, and their superstitions, which were "intolerable" to many and which he considered incompatible with any philosophy.

In other writings, Voltaire spoke positively about Judaism in comparison to Christian fundamentalism and praised the religious tolerance of ancient Judaism-although elsewhere he strongly criticizes Judaism's intolerance (then in comparison to the Enlightenment ideal). As on this point, Voltaire's statements on Judaism are also, on the whole, double-edged. On the one hand, he strove to make "Jewish superstition" seem irrelevant to the historical context; on the other hand, he gives Judaism a great deal of space in his reflections. While he castigates Jewish traditions as barbaric, his commitment to tolerance leads him to recognize Judaism and advocate Jewish rights.

Voltaire rigorously rejected the popular and state persecution of Jews in the Middle Ages. In particular, he sharply rejected the Christian motives of the persecution of the Jews. Thus he wrote one of his most forceful appeals for tolerance from the perspective of Rabbi Akiba. The persecution of a religion to which Jesus himself had belonged was absurd, he said: "He lived as a Jew and died as a Jew, and you burn us because we are Jewish." Jacob Katz, however, pointed out that Voltaire's resentment of Judaism was precisely the same as the motives of Christian anti-Judaism.

Voltaire's views made an important contribution to the emerging emancipation of Jews in the 18th century, but at the same time his statements served as a justification for future, racially motivated anti-Semitism. After Voltaire's death, the Polish Talmudist Zalkind Hourwitz, librarian to the French king, summarized his attitude and work as follows:

"The Jews forgive him all the evil he did them, on account of the good he brought them, perhaps unintentionally; for they have now a little respite for some years, and this they owe to the progress of the Enlightenment, to which Voltaire, by his numerous works against fanaticism, has certainly contributed more than any other author."

- Zalkind Hourwitz

Many of Voltaire's statements about Jews were exploited for propaganda purposes by the French history teacher Henri Labroue (1880-1964) in German-occupied France in the pamphlet Voltaire Antijuif. Labroue produced a book on the history of the French Revolution in the Gironde and was originally a man of the left and a Freemason. He organized an anti-Semitic exhibition in 1941 called Le Juif et la France and was offered a chair of "Jewish History" at the Sorbonne, but his lectures were boycotted. His annotated collection of quotations from Voltaire of 250 pages appeared in 1942, with the permission of the German propaganda department. It undercuts Voltaire's Enlightenment ideals. An anonymous article printed in the resistance journal J'accuse reacted to this by quoting from Voltaire's dictionary, among other things, to show the incompatibility of this appropriation with Voltaire's ideas of tolerance. In the judgment of Léon Poliakov, however, such a compilation of Voltaire's anti-Semitic remarks was a lightweight and quite in keeping with Voltaire's tendency. Several Voltaire scholars, however, have rejected quite a few of Labroue's quotations and comments.

Candide and the slave

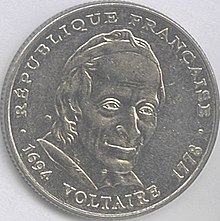

French 5 francs coin (1994) commemorating the 300th anniversary of Voltaire's birth

Statue of Voltaire in Ferney, 1890, Sculptor: Émile-Placide Lambert (1828-1897)

Footnotes

- ↑ Master of the chair was the astronomer Jérome Lalande, Benjamin Franklin led him to the temple, his guarantor was the historian Abbé Cordier de St. Firmin, and Count Stroganov prepared him for admission. His mason's apron came from Claude Adrien Helvétius.

- ↑ According to some authors, Voltaire partially moved away from these positions in his later years. Cf. Karl Vorländer: Geschichte der Philosophie (1902), further Franz Strunz: Voltaires Tod. In: Aufklärung und Kritik 1/2000, p. 116 ff. Strunz: "On the other hand, he was repeatedly overcome by doubts about the immortality of the soul, about the existence of God, about the hope of an afterlife. To Condorcet, for instance, he wrote on 4 April 1777 that he would probably soon present himself 'up there or down there or nowhere'."

Reference data (person): GND: 118627813 | LCCN: n80126267 | NDL: 00459873 | VIAF: 36925746 |

| Personal data | |

| NAME | Voltaire |

| ALTERNATE NAMES | Arouet, François-Marie (real name) |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | French writer and philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 21 November 1694 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| STERBEDATUM | May 30, 1778 |

| DESTINATION | Paris |

Questions and Answers

Q: Who was Voltaire?

A: Voltaire was a French philosopher born in 1694 and died in Paris in 1778.

Q: What did Voltaire think of France at the time?

A: Voltaire did not like France at the time because he thought that it was old fashioned.

Q: What did Voltaire think about the Church?

A: He did not like the Church and thought that people should be allowed to believe what they want.

Q: How long did Voltaire live in exile in England?

A: He lived in exile in England for three years from 1726 to 1729.

Q: What kind of philosophy did he study while living there?

A: He studied the philosophy of John Locke while living there.

Q: What type of God did he believe in?

A: He believed in a God, but not one personally involved with people's lives, which is called Deism.

Q: Why wasn't he allowed to be buried in a church when he died?

A: When he died, he was not allowed to be buried in a church because he didn't believe in the Christian God.

Search within the encyclopedia

_-001.jpg)