Veliky Novgorod

![]()

Novgorod is a redirect to this article. For the major city on the Volga, see Nizhny Novgorod. For other meanings, see Novgorod (disambiguation).

Veliky Novgorod (Russian Вели́кий Но́вгород), until 1999 Novgorod, is a major city in Russia with 218,717 inhabitants (as of 14 October 2010). It is located about 164 km south-southeast of Saint Petersburg on the Volkhov River north of Lake Ilmen and is the administrative center of Novgorod Oblast in the Northwest Federal District of Russia.

Until 1999, the city was officially called only Novgorod, also spelled Novgorod (Russian Новгород). Veliky Novgorod literally means Great Novgorod ("great" in the sense of "important"). Earlier names (as exonyms) were German Navgard, Naugard, Neugarten, Neugard and Old Norse Hólmgarðr.

As one of the oldest cities in Russia, Veliky Novgorod celebrated its 1150th anniversary in September 2009. In the 9th century Novgorod was the first capital of the young Kievan Rus. From the 12th to the 15th centuries, Novgorod was the capital of the influential, trade-oriented Republic of Novgorod and an important mediator between Rus and the West before becoming part of the centralized Russian Empire. Novgorod's architectural heritage has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1992. According to a 2010 survey, Veliky Novgorod is one of Russia's most livable cities.

Geography

Geographical position

Novgorod is located in the northwest of the European part of Russia and is 164 kilometers from Saint Petersburg and 494 kilometers from Moscow. From south to north the river Volkhov cuts through the city. It is situated at an average altitude of 25 meters. The city territory has an area of 90 square kilometers. About 60 percent of the surrounding area is forested, mainly with elms. The south of Novgorod near Lake Ilmen is very rich in marshland. Overall, Veliky Novgorod is surrounded by extensive moorland and forest areas, where peat in particular is extracted.

The geographical location is favorable for transport, as the rivers Lowat, Shelon, Msta and Volkhov, which flow into the lake, open ideal transport routes. The Volchov flows into Lake Ladoga, from which one can get directly to the Baltic Sea through Saint Petersburg. Via the rivers in the south of Novgorod there is a connection to the Black Sea.

Geology

The city is located in the East European Plain and in the easternmost part of the Baltic Land Ridge. Geologically, the city is located on the Russian Table, which consists mostly of unfolded young Proterozoic to Cenozoic sediments, which here cover large areas of the ancient continent Fennosarmatia. Unlike its surrounding mountains, the Russian Table is poor in mineral resources despite its size. During the last ice ages, Scandinavian glaciers reached as far as the Novgorod region. The shallow Lake Ilmen (only 2.5 to 10 metres deep) is the remnant of a glacial melt lake, in which fluviatile and periglacial sediments are widespread.

City breakdown

The city is roughly divided into the historic city centre and the new town, which was built outside the former city walls. The old town is divided into the St. Sophia side, named after St. Sophia's Cathedral, on the western bank of the Volkhov River, and the commercial side on the eastern bank. The St. Sophia side consists of three quarters of the city, in the north the Nerevsky quarters, in the west the Zagorodsky quarters and in the south the Lyudin quarters, the former potters' quarters. The commercial side consists of the Plotniki Fifth, formerly the Carpenters' Fifth, to the north, and the Slawno Fifth to the south. These quarters are called konzy (literally "ends", singular konez) in Russian, which is specific to Novgorod.

In the eastern center on the Sophia side is the Novgorod Kremlin. The sides have been connected since the 11th century by a large wooden bridge; it was sporadically destroyed by fire, floods or ice. In the western center of the trading side was the medieval marketplace, Yaroslav's Court and the offices of foreign merchants, in particular the Peterhof of the Hanseatic League. The New Town is much more developed on the western side of the river than on the eastern. The districts of Koltovo, Grigorovo, Sapadiny, Novaya Melnitsa, Leshno, Pankovka and Bely Gorod adjoin the Sophia side there from north to south, and the Antonovo district on the trade side in the north.

Neighboring communities

Seven other rajons within the Novgorod oblast border on the Novgorod city rayon. These are clockwise from north to west: Chudovo, Malaya Vischera, Kresttsy, Parfino, Staraya Russa, Shimsk and Batetsky rajons. In the northwest the rayon borders on the Pskov oblast.

Climate

Novgorod with its humid climate is located in the cool temperate climate zone with influence of continental climate. In the climate classification it is classified as DfB, which means that (D) the coldest month has a temperature below -3 °C, the warmest month is above 10 °C, (f) all months are humid, and (B) the temperature is below 22 °C, but there are still at least four months warmer than 10 °C. The average annual temperature in the city is 4.3 °C. Although the annual precipitation is only 561 millimetres (for comparison Cologne: 798 millimetres), it is higher than the evaporation, which is why a humid climate prevails. The warmest months are June and July with an average of 15.7 and 17.3 °C respectively, the coldest months are January and February with an average of -9.2 and -8.2 °C respectively. The most precipitation falls in the months of July and August with an average of 72 millimeters each, the least in February with an average of 23 millimeters.

| Veliky Novgorod | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monthly average temperatures and precipitation for Veliky Novgorod

Source: Roshydromet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Novgorod in the 17th century, drawn by Adam Olearius (north is on the left)

City fifth of the Sophia and trade side

History

prehistory and early history

The surroundings of Novgorod are characterized by many forests, lakes, marshes and marshlands, which made the area almost impenetrable and the rivers the main routes of communication. Along the banks of the rivers and lakes were the only areas suitable for settlement.

In Rurikovo Gorodishche near Novgorod there was a Neolithic settlement since the 3rd millennium B.C. The first settlers in the area around and north of Lake Ilmen were Finno-Ugric hunters and fishermen as well as the Slavic tribe of Slovenes.

The newcomers introduced agriculture. Since the 8th or early 9th century, Slavic Ilmense Slovenes also settled there.

Novgorod Rus

Scandinavian Varangians also passed through this region on the trade routes to the Byzantine Empire since the 8th century. In the middle of the 9th century, one of their settlements, the present Rurikovo Gorodishche, was established on the eastern bank of the Volchov at the outlet of Lake Ilmen, two kilometres south of present-day Novgorod. This settlement initially developed into the central trading post of the region.

For 862 the settlement was first mentioned in ancient Russian chronicles. The Varangian prince Ryurik established the center of his dominion here.

Novgorod in Kievan Rus

See also: List of the Princes of Novgorod

Around 911 Kiev became the new center of Rus. Old Novgorod lost this function. Around 969 Vladimir I became the first separate prince of Novgorod. In 988/989 Novgorod became the seat of the second eparchy (bishopric) of Rus. The first bishop was Joachim Korsunianin.

About this time the present Novgorod (New Town) was established as a merchant settlement at some distance from the old castle Rurikovo Gorodishche. The first churches were probably the wooden Church of St. Sophia and the Church of St. Joachim and Anna.

Yaroslav the Wise had been Prince of Novgorod since about 988. In 1015, after the death of his father Vladimir I, he sought control of Kiev. Since the Novgorodians supported him in this successful enterprise, he gave them extensive rights, which formed the basis for the future boyar order in Novgorod. These privileges led to a structural division of the city. The courts of the boyars were now no longer under the jurisdiction of the prince and formed the basis for the five quarters (конец, end). Between these quarters settled free artists and merchants, who continued to be under the jurisdiction of the prince. These areas were subdivided into hundred-ships (sotni) and administered by so-called "thousand-ship leaders" (tysjazkie) and "hundred-ship leaders" (sotskie).

In 1030, during a visit, Yaroslav ordered that 300 children of elders and priests be instructed in reading.

Around 1030 the seat of the prince of Gorodishche was probably also moved to the Kremlin of Novgorod.

The social structure consisted of three strata: Rich merchants and bankers (at the same time landowners) were at the top; ordinary merchants were representatives of the middle class; craftsmen and day laborers belonged to the lower class of the population.

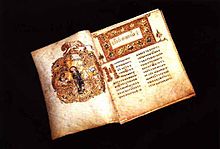

Besides trade, culture also flourished. Famous icon painters such as Theophanes the Greek and Andrei Rublyov worked in the city. In 1056/1057 the Ostromir Gospels were made for the Novgorod governor Ostromir.

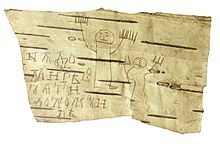

In the High Middle Ages Novgorod was the only city in Europe, apart from Constantinople, where not only the nobility and the clergy, but also the common people could read and write. This is evidenced, among other things, by over 1000 letters written on birch bark in the Old Novgorod dialect (so-called birch bark documents) found during archaeological excavations. They tell about everyday life in the medieval town. On July 26, 1951, the first birch bark fragments were discovered during excavations by Nina Akulova in Velikaya Street. Meanwhile, more than a thousand birch bark fragments are known.

The ties of the Norwegian rulers to the city can also be seen in the fact that they used Novgorod as a place of refuge several times. Olav I Tryggvason fled there before 1000, Olav II Haraldsson from 1027 to 1030. His son Magnus I was educated in Novgorod until 1035 and was brought back by Norwegian nobles after the murder of his father. Harald III also sought refuge in Novgorod when danger threatened. Olav I Tryggvason and Magnus I spent their childhood and youth here and had close ties to the city throughout their lives.

Republic of Novgorod from 1136 to 1478

→ Main article: Republic of Novgorod

In 1136, a general uprising against the prince ended in victory for the boyars. Subsequently, the prince was only an official of the boyar republic. He could only perform his function as a judge if his judgment was confirmed by the Possadnik, the head of the Boyar Council, who increasingly directed foreign policy and administered justice, led the army and filled the offices, thus assuming the role of the prince. As a direct result of the revolt, Prince Vsevolod II was expelled and Svyatoslav Olegovich of Chernigov was installed. The second important office was held by the Tysjackiy, the Thousand Leader, who led the people's posse and was responsible for taxes, tributes, and for the market. The bishopric, created in 1035, rose to archbishopric in 1165.

Spared from the ravages of the Mongol raids, Novgorod was for a time, especially under Alexander Nevsky, the center of the Russian Principalities and the seat of the Grand Prince. Beginning with Alexander Nevsky, Novgorod princes were elected from among the princes of Vladimir-Suzdal. The city became one of the largest city-states and developed a territory of about 30,000 km² in extent, with a further 1.5 million km² or so as far as the Urals in a tributary relationship. In the 14th century, the older part of the name weliki began to be interpreted as large in order to distinguish Greater Novgorod from other cities. In the 14th century the city area covered about 400 ha, the city castle (detinec) alone 11 ha. The population increased from about 50,000-60,000 in the 13th century to as many as 80,000 in the 15th century. Thus its population exceeded the size of the most important German cities such as Cologne, Nuremberg or Lübeck.

The expansion of power based on this development enabled the city to militarily repel the expansion of the Swedes in 1240 and that of the Teutonic Order in 1242. In total, Novgorod went to war 26 times against Swedes and 11 times against the Livonian Order of the Brothers of the Sword. The repulse in 1240 and 1242 succeeded, although Novgorod's German opponents, taking advantage of the Mongol invasion of Russia, together with Danes and Swedes shifted their military operations to Novgorod's territory. However, their campaigns failed at the Battle of the Neva and the Battle of Lake Peipus. On August 12, 1323, the Treaty of Gothenburg was signed between Sweden and Novgorod, which for the first time regulated the course of the border between the Russian and Swedish parts of Finland.

In the late Middle Ages Novgorod was a city dominated by the noble merchant class, recruited mainly from the large landowners and profiting greatly from the collection of tribute. They were joined by a class of full-time long-distance merchants who were primarily engaged in the western trade. A counterbalance was formed by a wetsche - a people's assembly dating back to Old Slavic traditions - in which non-noble population groups were also entitled to speak and vote. The oligarchic city republic, which elected the prince from the 12th century, and from 1156 the archbishop and the possadniks, a kind of mayor of the city, had good contacts with the Hanseatic League, which maintained one of its four offices there in Peterhof.

Novgorod had finally emerged as the main trade intermediary with the West in the 14th century. Since the transit trade of the Russian lands and also of the Tatars, who traded in spices and furs, with Western Europe via the Lithuanian territory was hampered by high customs duties and frequent encroachments, this position remained unchallenged in the following period.

Trade with Gotlanders and Hanseatic League

Already in the 10th century contacts of foreign traders with Novgorod are documented. For example, Ravnur Hólmgarðsfari from Tønsberg in Norway, who is mentioned in the Faring saga, already bears the Norse name for Novgorod in his name, which thus means Novgorodian.

After the foundation of Lübeck, Hanseatic merchants began to sail across the Baltic Sea to Gotland in the middle of the 12th century. The first contacts to Novgorod were mediated via the merchants there. The merchants from Gotland maintained the so-called Gotenhof on the trading side, in the use of which the Hanseatic merchants initially participated. In addition, there was also a guild yard of the Gotlanders. In 1192, the Hanseatic League established its own court, the so-called Peterhof. The name of the Kontor goes back to the church of St. Peter that was built in it. In addition to residential buildings, the yard also contained economic facilities such as a bakery, brewery, infirmary, baths and prison. The Hanseatic merchants had their own legal jurisdiction on the farm, but also had to ensure legal order themselves. However, according to the Novgorod Schra, the merchants did not have the right to stay permanently in Novgorod. According to the seasons, a distinction was made between winter and summer merchants. The merchants transported mainly raw products to Western Europe, especially furs, wax, honey and wood. In return, they brought mainly finished products to Novgorod, such as wine, beer, cloth, weapons and glass, but also salt, herring, metal (silver), spices, tropical fruits, horses and amber. When a great famine broke out in Volchov in 1230, they transported mostly grain. With the decline of the Gothic Olafshof in the 14th century, which was subsequently leased by the Hanseatic League, the Hanseatic League gained a monopoly in trade with Novgorod. The ship type of the cog also contributed to the strengthening of this monopoly. Between 1396 and 1462, there is archaeological evidence of the import of glass products such as finger rings and window glass. In the 15th century, trade slowly declined as the exchange of goods was increasingly shifted to the Livonian cities. The Peterhof in Novgorod was not closed after the conquest of the city by the Moscow Grand Duke Ivan III in 1478. On the contrary, the prerogatives of the Hanseatic League were reaffirmed in 1487. However, in the course of his disputes with Maximilian of Habsburg, Ivan III had the court closed on November 6, 1494. The confiscation brought the Grand Prince 96,000 marks. In 1514 the Gotenhof and the Peterhof were reopened, and the courts seem to have been in use as late as 1560. In the 17th century the Swedes' Court was built on Slavnaya Street to the northeast of the old square.

Coinage and long-distance trade

The city of Novgorod, due to its strong trade relations with foreign merchants, was the starting point of the development of coinage in Russia. From the second half of the 13th century, it became common to use silver bars as a monetary unit. The weight of these bar ingots was 205 grams, corresponding to the old Russian unit of weight, the hryvnia. Smaller pieces of silver, called rubles, were separated from the larger bars in smaller trading transactions. Coins were first minted in northwestern Russia in the 13th/14th centuries, initially in Novgorod and Pskov, and later in Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod, and Suzdal.

When the circulation of money increased at the beginning of the 15th century and all the grand princes began to mint money, Novgorod went over to minting its own coins from 1420. Novgorod had previously adopted the Livonian currency for a short time.

From the 10th to the 13th century, mainly amphorae, glass products, slate spindle whorls and walnuts arrived in the city from the Byzantine Empire. Amber, which was found in geological layers in the Dnieper region, was also imported. Around 1100 the import experienced a short interruption, which can be explained by a conflict between the cities of Kiev and Volchov. With the destruction of Kiev in 1240 by the Mongols, the Dnieper route lost most of its importance, whereas the import of boxwood for comb production continued via the Volga route. Especially in the 14th century, glazed ceramics from the Tatar Khanate of the Golden Horde reached Novgorod via this route.

Moscow period from the 15th to the 19th century

For a long time Novgorod was in competition with the Grand Duchy of Moscow, Novgorod representing the oligarchic-city noble social order, Moscow the autocratic-princely one. Added to this opposition was the fight against Novgorod's river piracy (Ushkuiniki), which prompted Moscow to unleash an uprising against Novgorod's rule as early as 1397. Moscow's steady rise in power increasingly threatened the seesaw policy that Novgorod had long successfully practiced between Moscow, Tver, and Lithuania, as Tver became less and less important and Lithuania's forces were bound by disputes in Bohemia, Hungary, and with the Teutonic Order after its union with Poland. Nor did Novgorod succeed in breaking away from the suzerainty of the Metropolitan of Moscow. In 1441 the city paid tribute to Moscow for the first time.

After a successful attack, Moscow was able to strengthen its influence on Novgorod's foreign and domestic policy after 1456. The Vetshe was no longer allowed to deed in its own name. After this defeat, the Novgorod boyar oligarchy had to realize in 1458 that Moscow had in the meantime gained a clear superiority. After the Novgorod defeat at the Battle of Shelon (1471) and renewed anti-Moscovite movements, the final incorporation into the Grand Duchy followed in 1478, with Moscow pretending to want to prevent a church schism in Russia in favour of the Lithuanian Catholics. Numerous Novgorod boyars, their clientele and merchants were relocated to Moscow, where a separate Novgorod quarter was created near the Kremlin. In return, Moscow servants took over the estates of the dispossessed. The abolition of the Vetche bell symbolized the end of the Novgorod city-state.

During the Livonian War, the city was destroyed in 1570 by the troops of Tsar Ivan the Terrible after he suspected that the citizens of Novgorod were trying to ally with Poland-Lithuania. On January 15, 1582, the Treaty of Yam Zapolski (Truce) was concluded between Poland-Lithuania and Russia in the village of Yam Zapolski near Novgorod. During the period of turmoil in the Polish-Russian War 1609-1618, Novgorod was occupied and destroyed by the Swedes between 1611 and 1617. The above-mentioned wars and events caused the number of Novgorod's inhabitants to drop to 8000, and its political and economic importance declined to the same extent.

The city then experienced a boom, but after the founding of Saint Petersburg in 1703 its economic and strategic importance as Russia's outpost in the northwest declined. The city structure underwent a serious change after 1778, when the new general development plan drawn up by Nikolai Chicherin (Николаи Чичерин) was signed by Empress Catherine II. While the semicircular city wall on the Sophia side was preserved, the plan otherwise envisaged rectangular streets. For this purpose, the street structures that had grown over centuries were destroyed.

In 1859 the design of Mikhail Osipovich Mikeshin (1835-1896) won the competition for the Novgorod Monument to a Thousand Years of Russia, which was followed with great interest by the public.

Soviet Union, World War II

In the Soviet Union, Novgorod was part of the Leningrad region, which included the rayons or districts of Murmansk, Pskov, and Cherepovets. Although the Novgorodians had joined the council (soviet) movement in Russia by the end of 1918, they tended to lean toward the moderate socialist parties.

During the German-SovietWar (1941-1945), Novgorod was under German occupation from August 15, 1941 to January 20, 1944, and suffered great damage as a result. Among other things, Bolko von Richthofen destroyed the library of the Novgorod Antiquities Society and the museum in Staraja Russa on behalf of the German Foreign Office during the Russian campaign. At the request of the Wehrmacht, on October 4, 1941, Heinrich Himmler ordered Sonderkommando Lange to be airlifted to Novgorod to kill the inmates of three asylums for psychiatric patients. The premises were needed to house troops. After the liberation in the course of the Leningrad-Novgorod operation, the reconstruction of the city was started already at the beginning of 1944. On July 5, 1944, the Novgorod Oblast was established.

Recent history

In 1999 the city regained its historical name Veliky Novgorod. On 13 July 2000, excavations revealed the so-called Novgorod Codex, a wax tablet book from the first quarter of the 11th century consisting of three bound limewood plates with a total of four pages filled with wax. In September 2004, Veliky Novgorod hosted the first meeting of the Valdai Club, an annual roundtable of experts on Russia's foreign and domestic policies. Vladimir Putin was one of the participants. On October 28, 2008, Veliky Novgorod received the "Glorious Combat City" award from President Dmitry Medvedev for the "courage, perseverance and mass heroism in defending the city in the struggle for freedom and independence of the Fatherland." In 2009, the city celebrated the 1150th anniversary of the first written record. From 18 to 21 June 2009 Novgorod hosted the XXIX. International Hanseatic Days of New Era took place in Novgorod.

Population development and structure

The population of Veliky Novgorod was 218,717 in 2010, ranking it 86th among Russia's largest cities. Novgorod reached the highest population in its history, with over 229,116 inhabitants, in the early 1990s; in subsequent years, the number shrank considerably, as was the case in most cities in Russia during the economic crises of the 1990s. The following table shows the evolution of the population of the city of Novgorod since about 1825. From 1959 to 1979, the population more than tripled. A significant population decline, on the other hand, occurred during the years of the Second World War.

|

|

|

|

|

City map from the first half of the 18th century

Russian stamp for the 1150th anniversary of the city in 2009

Birch bark fragment no. 202 with writing and drawing exercises of the 7-year-old boy Onfim (13th century)

Novgorod in the Hanseatic trade

.png)

Novgorod (pink) with its dominion in the 13th century

Battle depiction between Novgorod and Suzdal in 1170, fragment of an icon from 1460

Ostromir Gospels in the copy of 1056/57

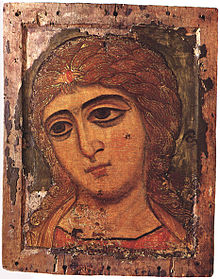

Novgorod icon of the Archangel Gabriel, 12th century.

Search within the encyclopedia