Vein

Veins (Latin singular vena, in technical compounds also phlebo- from Greek genitive singular φλέβας phlébas, to Ancient Greek φλέψ phleps, German 'vein') or blood veins are blood vessels that carry blood to the heart. In an adult human, they carry about 7000 litres of blood back to the heart every day. In doing so, the veins in the legs have to transport the blood to the heart against the force of gravity. The blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart are called arteries. Most of the body's veins are concomitant veins, which means they run parallel to their arterial counterpart.

The veins of the systemic circulation transport deoxygenated blood, those of the pulmonary circulation oxygenated blood. Oxygen-poor blood is darker than oxygen-rich blood. However, the bluish appearance of skin veins is not solely related to the oxygen content of the venous blood. Skin veins appear blue primarily because the long-wave red light has a greater depth of penetration into the tissue than the blue and is thus absorbed by the dark blood of the veins. The short-wave blue light, on the other hand, is reflected; thus the veins appear blue at a tissue depth of 0.5 to 2 millimeters (see also Blue Blood). Since arteries are much thinner than their accompanying veins while having thicker walls, they are not visible through the skin.

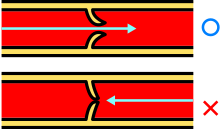

The blood pressure in veins is significantly lower than in arteries; together with capillaries and venules, they belong to the low-pressure system of the circulatory system. The skeletal muscles serve as a natural pump for the blood flow in the veins. With each contraction, the muscles push the blood against gravity from below towards the heart. Dozens of venous valves act like check valves to ensure that the blood does not fall back down when the muscle relaxes.

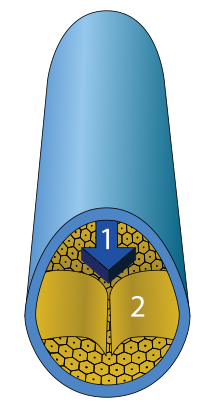

Cross section of a vein with vein wall, flow direction and vein valve

Structure

Veins, like all blood vessels, show a typical three-layered wall into tunica interna (intima), tunica media (media) and tunica externa (tunica adventitia). The wall of the veins is usually thinner than that of the corresponding arteries, especially the tunica media. Here, the smooth muscle cells are forced apart into strands by collagenous connective tissue, which also makes the media appear more loosened than in arteries. The media shows a suggested two-layered structure with an inner spiral winding and an outer flatter winding. Some large veins such as the inferior vena cava have only longitudinal muscles. Larger leg veins such as the great saphenous vein are subject to high hydrostatic pressure, which is why they have a strong wall similar to arteries.

Unlike arteries, many of the small and medium-sized veins are equipped with venous valves to prevent the blood from flowing back. No venous valves are found in the veins of the head, viscera, vertebral canal, and the large veins near the heart. In the arteries, the pumping pressure of the heart is sufficient to prevent backflow.

Action of the venous valves

Vein pressure

Venous pressure, i.e. the blood pressure in veins, is significantly lower than in arteries; together with capillaries and venules, they belong to the low-pressure system of the circulatory system. In the venules there is still a blood pressure of 15-20 mm Hg, in the large veins outside the thorax of 10-12 mm Hg. The blood pressure in the large veins near the heart is called the central venous pressure. It fluctuates depending on respiration and cardiac activity and is on average 3-5 mm Hg.

Search within the encyclopedia