Vaccine

![]()

This article or section needs revision. More details should be given on the discussion page. Please help improve it, and then remove this tag.

A vaccine, also called a vaccine or vaccin (lat. vaccinus "coming from cows"; see vaccination), is a biologically or genetically produced antigen, usually consisting of pieces of protein (peptides) or segments of genetic material or killed or attenuated pathogens.

A vaccine may consist of an antigen from a single pathogen or a mixture of antigens from different pathogens or strains. The vaccine may also contain additives to enhance its effect.

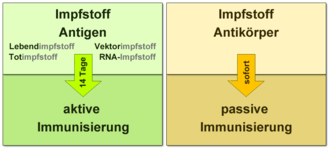

The vaccine is intended to stimulate the immune system of the vaccinated person to form specific antibodies against a pathogen or against a group of pathogens. The antigenic effect of the vaccine evokes an immune response in the vaccinated person through so-called active immunisation, which consists not only of antibodies but also of specialised T-helper cells. The immunity achieved protects against the respective disease; depending on the pathogen, this protection can last for several years or even for life.

In contrast, passive immunization involves injecting antibodies to treat an acute infection. This saves the approximately 14-day waiting period, but does not cause permanent immunity of the patient.

.jpg)

Usually vaccine is injected into a muscle by syringe

In active immunization, the vaccine contains or produces an antigen against which the patient's immune system forms its own antibodies within 14 days, resulting in lasting immunity. If only antibodies are vaccinated, one speaks of passive immunization, the protection occurs immediately, but lasts only for a short time.

Attenuated live vaccine

→ Main article: Attenuation

Live vaccines contain attenuated bacteria or viruses that can usually still multiply and trigger an immune response, but usually not a disease. An attenuated virus that is still replicated by a cell is also called a "live vaccine". The term has become established, although strictly speaking it is not correct, because viruses are not living organisms.

A live attenuated vaccine is usually much more effective than an inactivated vaccine. In rare cases, after the application of such a vaccine, a mutation (reversion) towards the non-attenuated initial form can occur during the possible multiplication of the pathogens, through which the disease can occur after all.

Examples of attenuated vaccines include the oral polio vaccine (OPV) abandoned in Europe, which very rarely caused vaccine poliomyelitis, the MMR(V) vaccine, the smallpox vaccine of the time, the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, and vaccines against yellow fever. Both live and inactivated vaccines are available for typhoid vaccination. Attenuation is usually achieved by serial infections of non-species cell cultures, embryonated chicken eggs or laboratory animals, in which the respective pathogen adapts to the new host species and often simultaneously loses adaptations to the species of the inoculated, resulting in a reduction in pathogenicity.

Some live vaccines are treated by additional methods. Cold-adapted strains can only replicate at temperatures around 25 °C, which limits the viruses to the upper respiratory tract. In the case of temperature-sensitive strains, replication is restricted to a temperature range of 38-39 °C and, again, infestation of the lower respiratory tract does not occur.

oral polio vaccine

Dead Vaccine

→ Main article: Dead vaccine

Inactivated vaccines contain inactivated or killed viruses or bacteria or components of viruses, bacteria or toxins. These can no longer multiply in the body or poison it, as tetanospasmin could, but they also trigger a defence reaction (immune response). Examples are the toxoid vaccines and vaccines against influenza (influenza vaccine), cholera, bubonic plague, hepatitis A or hepatitis B (hepatitis B vaccine).

Dead vaccines are divided into:

- Toxoids: Toxoids are detoxified toxins of pathogenic microorganisms. These vaccines are used in cases where it is not the pathogens themselves but primarily their toxins that cause the disease symptoms, as in the case of tetanus and diphtheria.

- Inactivated whole-particle vaccines: Inactivation of viruses by fixation using a combined application of formaldehyde, beta-propiolactone and psoralen.

- Cleavage vaccines: destruction of the virus surface with detergents or strong organic solvents.

- Subunit vaccines: the surface is completely dissolved and specific components (haemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins) are purified out. Another possibility is to produce the subunits recombinantly. Subunit vaccines are only slightly immunogenic, but have few side effects.

Inactivated vaccines require immunostimulatory adjuvants, most commonly alumiunium adjuvants.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a vaccine?

A: A vaccine is an invented preparation that is given to prevent a specific infectious disease. It usually works against the microorganism for which it was prepared and is administered through an injection called vaccination.

Q: How does a vaccine work?

A: At its best, a vaccine gives immunity to an infectious disease caused by a particular microorganism (bacteria or virus). For example, the flu vaccine makes it very much less likely that a person will get the 'flu.

Q: What are vaccines made of?

A: Vaccines can be made from something that was alive or built up by viral biochemistry. Each vaccine has its own history and what is true of one might not be true of another.

Q: Where does the word "vaccine" come from?

A: The word "vaccine" comes from the Latin vacca, meaning "cow".

Q: Who first used cowpox to protect people against smallpox?

A: In 1796, Edward Jenner used a milkmaid infected with cowpox (variolae vaccinae) to protect people against smallpox.

Q: What is the use of vaccines called?

A: The use of vaccines is called vaccination.

Q: Was vaccination done before Jenner's discovery in 1796?

A: Yes, powdered smallpox material was blown up the nostrils of subjects prior to Jenner's discovery in 1796.

Search within the encyclopedia