Utopia (book)

Utopia [uˈtʰoːpi̯ɑ] (IPA phonetic transcription) - first printed in 1516 under the title: Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, De optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia ("A truly golden little book, no less salutary than entertaining, Of the best constitution of the state and of the new island of Utopia") - is a philosophical dialogue written in Latin by Thomas More (1478-1535) in the early 16th century. It was first published in Belgium at the beginning of the 16th century. In it, the London burgher and undersheriff, later Speaker and Lord Chancellor, presents a description of a distant ideal society, thus giving rise to the genre of the social utopia.

It was first published in Louvain in 1516 at the instigation of Morus's close friend, the humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam (c. 1467-1536). The work was published with the help of the Antwerp town clerk Pieter Gillis (Latinized Petrus Aegidius; 1486-1533) and the printer of the University of Louvain Theodor Martin von Aelst; further printings followed in Paris in 1517 and in Basel in 1518. The first translation into German - under the title Von der wunderbarlichen Innsel Utopia genant/ das ander Buch/ ... - appeared in Basel in 1524 and contained only the second part.

The frame story is a stay of Morus in Antwerp, where he meets his esteemed friend Peter Aegidius and a stranger who is introduced as a well-read, well-travelled Portuguese and alleged travelling companion of Vespucci. Recalling their conversation, Morus relays tales and accounts of the world traveler who claims to have lived for a time on an island called Utopia among the Utopians there. The society described, with democratic features, is based on rational decision-making, principles of equality, industriousness, and the pursuit of education. In this republic, all property is communal, lawyers are unknown, and inevitable wars are preferably fought with foreign mercenaries.

The book was so influential that thereafter novels depicting an invented positive society are called utopian novels or utopias. Examples include La città del Sole (1623; Engl. The Sunshine State) by Tommaso Campanella, Nova Atlantis (1627; Engl. New Atlantis) by Francis Bacon, A Modern Utopia (1905; Engl. Beyond Sirius) by H. G. Wells, Island (1962; Engl. Island) by Aldous Huxley, or Ecotopia (1975; Engl. Ecotopia) by Ernest Callenbach following Utopia.

Today, the genre of the utopian novel is often considered to be the realm of science fiction.

The woodcut in the 1516 edition shows an island whose outline resembles a crescent moon

.jpg)

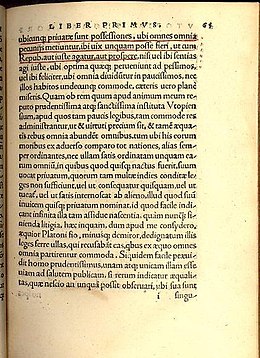

Frontispiece of the 1518 edition

The life of the Utopians

The first part of the work has a framework plot, in which Thomas More made a detailed criticism of the political and social conditions of the time in Europe, especially England. He strongly denounced, for example, the practice of capital punishment, which in England threatened even thieves, so that for them there was no difference between stealing and murder. In the second part, he describes the organization of the future state of Utopia and the living conditions of its inhabitants.

Utopians live in cities and form family groups. Adults enter into a monogamous marriage. There is generally a patriarchal hierarchy, and the elders rule over the younger ones. Superfamilially, the community is organized like a monastery, with communal kitchens and communal meals. An annually elected head ("phylarch") supervises a family association of 30 families. Private property does not exist, everyone receives free of charge the goods produced by the community for personal use, which he desires. Men and women work as craftsmen six hours a day. In what craft a citizen is trained, he can decide himself. Work is compulsory, and Utopians are sent out into the countryside on a rotational basis to farm communally. Schooling is compulsory for children. The especially gifted receive a scientific or artistic education. Scientific lectures are open to the public, and attending them is the most popular pastime among Utopians. The citizens attach particular importance to providing the best possible health care for everyone who is ill. Men and women regularly practice for military service. War criminals and criminals, some of them bought from abroad as death row inmates, must perform forced labor. Religious tolerance prevails in the secularly organized community.

The state is a republic. Each city is governed by a senate composed of temporary elected officials. The head of each city is elected for life; if he develops tyrannical traits, he can be deposed.

The Utopians do not know money transactions. But they are said to accumulate much of it through an overproduction of goods, and use it to maintain mercenary armies or to trade. The Utopians themselves do not value gold.

Cities may only reach a certain size. Overpopulation is compensated by migration or the formation of a colony abroad. Conversely, if there is a shortage of inhabitants, there is a reflux from the colonies or overpopulated cities.

.jpg)

Illustration of the conversation with Raphael Hythlodeus in the first part of the Basel edition of 1518

Abolition of private property

In the first part, there is a conversation before a meal together, discussing various circumstances, what would be the best constitution of a state and where possible. Here, Morus has his interlocutor Raphael Hythlodeus say on the question of property:

"Quanquam profecto mi More (ut ea uere dicam, quae meus animus fert) mihi uidetur ubicunque priuatae sunt possessiones, ubi omnes omnia pecunijs metiuntur, ibi uix unquam posse fieri, ut cum Republica aut iuste agatur, aut prospere, nisi uel ibi sentias agi iuste, ubi optima quaeque perueniunt ad pessimos, uel ibi feliciter, ubi omnia diuiduntur in paucissimos, nec illos habitos undecunque commode, caeteris uero plane miseris.

[...] haec inquam, dum apud me consydero, aequior Platoni fio, minusque demiror, dedignatum illis leges ferre ullas, qui recusabant eas quibus ex aequo omnes omnia partirentur commoda. Siquidem facile praeuidit homo prudentissimus, unam atque unicam illam esse uiam ad salutem publicam, si rerum indicatur aequalitas, quae nescio an unquam possit obseruari, ubi sua sunt singulorum propria. Nam quum certis titulis, quisque quantum potest, ad se conuertit, uantacumque fuerit rerum copia, eam omnem pauci inter se partiti, reliquis relinquunt inopiam, fereque accidit, ut alteri sint alterorum sorte dignissimi, quum illi sint rapaces, improbi atque inutiles, ..."

"And in general, my Morus - to say honestly what I think - it seems to me that wherever there is private property and where everyone measures everything according to the value of money, it is hardly possible for justice to prevail in a state and happiness to reign, unless one were of the opinion that justice prevails there, where the best comes to the worst, or that happiness prevails there, where everything is distributed among a few and even these few are not well off in every respect, but the rest are quite bad.

[As I said, when I think of this, I understand Plato better and am less surprised that he refused to give laws to people who did not want to know anything about an equal distribution of all goods of life among all. For the wise man easily recognized that this is the only, sole way to the general good, if one decrees equality of circumstances; but this can hardly ever take hold where the individual disposes of property. For if every one, by reference to guaranteed legal titles, may direct what he can to his mill, there may be as much as he likes: but only a few ever divide the whole wealth among themselves, and leave the rest in poverty. It is generally the case that some deserve the lot of others: those are robbers, scoundrels, and good-for-nothings, ..."

- Thomas Morus (1478-1535): Utopia, Liber I. (Translation by Alfred Hartmann, first published by Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel 1947.)

Considerations on the distribution of goods in ratios

Search within the encyclopedia