Utilitarianism

![]()

This article deals with the normative form of teleological ethics. For the text by the English philosopher John Stuart Mill, first published in 1861, see Utilitarianism.

Utilitarianism (Latin utilitas, utility, advantage) is a form of purpose-oriented (teleological) ethics (ethics of utility) that appears in various variants. Reduced to a basic classical formula, it states that an action is morally right precisely when it maximizes the aggregate total utility, i.e. the sum of the welfare of all concerned. In addition to ethics, utilitarianism is also important in social philosophy and economics.

Different forms of utilitarianism exist, depending on other philosophical assumptions. Hedonistic utilitarianism, for example, equates human well-being with the sensation of pleasure and joy and the absence of pain and suffering, while other forms of utilitarianism require the fulfillment of individual preferences. Action utilitarianism judges actions individually by their tendency to bring about good consequences, while rule utilitarianism focuses on following rules. What all forms of utilitarianism have in common, however, is that they provide the sole criterion for possible consequences and real effects of moral judgment; accordingly, utilitarianism is a consequentialist ethics. Furthermore, it is a considerate and universalistic moral theory, because utilitarianism propagates an increase of the common good. In doing so, it politically advocates a vision of a paternalistic welfare state, led by technocrats, whose laws ensure "the greatest possible happiness for the greatest possible number."

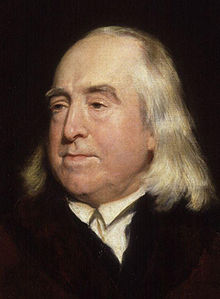

The utilitarian approach was systematically developed and applied to concrete issues by Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and John Stuart Mill (1806-1873). Bentham explains the central concept of utility in the first chapter of his "Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation" (first published in 1789) as follows:

"By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of any action according to its tendency to increase or diminish the happiness of that group whose interests are at stake [...] By 'utility' is meant that quality in an object whereby it tends to produce well-being, advantage, pleasure, good or happiness."

"Benefit" is therefore not to be equated with "utility". Moreover, modern utilitarian theories often do not operate with the concept of benefit, but with the broader concept of human well-being.

History of utilitarian theory

Predecessor forms

A first form of utilitarianism is found in the Chinese philosopher Mozi (479-381 BC). He founded the school of Mohism in ancient China and advocated a utilitarian ethic some 2200 years before one was formulated as a justifiable principle in Europe. Ancient hedonism, which goes back to the Cyrenaic school of philosophers founded by Aristippus of Cyrene, can also be interpreted in the broadest sense as a predecessor of classical utilitarianism.

The beginnings of utilitarian thought in modern Europe are found in Thomas Hobbes (Leviathan), whose basic ethical proposition is that "right" behavior is that which promotes our own well-being. Further, the justification of society's moral code depends on whether it promotes the well-being of those who follow it. With Francis Hutcheson, the criterion for morally good action was whether it promoted the welfare of humanity. His successor David Hume concluded that virtue and personal merit rest in those of our qualities that are useful to us - and to others.

Classic period

Jeremy Bentham was the first in Europe to advocate utilitarian ethics in the form of an elaborate system. In his work An introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, Bentham expressed that for him there were only two basic anthropological constants: The pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain. Suffering and pleasure, according to Bentham, determined the ethical criteria of human action and the causality of our actions. It is nature, he said, that guides man's path in suffering and pleasure. Bentham saw suffering and pleasure as the decisive motives for human action and thus advocated a psychological hedonism:

"Nature has placed mankind under the dominion of two sovereign masters - Sorrow and Joy. It is for them alone to point out what we should do, as well as to determine what we will do. Both the standard of right and wrong, and the chain of causes and effects, are fastened to their throne. They rule us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think."

According to Bentham, a person always strives for an object that he expects to give pleasure. From this, Bentham formulated the principle of utility, which states that all that is good is that which produces "the greatest happiness of the greatest number". Bentham later realized that the simultaneous maximization of two quantities does not provide a unique solution, which is why he later spoke only of the "Maximum Happiness Principle". Bentham's work focused on the application of this principle to the design of social order. In his writings, he developed not so much an individual ethic as a rational legislative theory. For Bentham, the quantity of happiness alone was decisive, which he expressed by the drastic phrase "Pushpin is of equal value [...] with poetry" ("Prejudice apart, the game of push-pin is of equal value with the arts and sciences of music and poetry. ") expressed. In contrast, John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), in his 1863 book "Utilitarianism", argued that cultural, intellectual and spiritual satisfaction also had a qualitative value, compared to physical satisfaction. A person who has experienced both prefers spiritual satisfaction to physical satisfaction. Mill states this in his famous saying:

"It is better to be a discontented man than a contented pig; better to be a discontented Socrates than a contented fool."

However, the calculative mapping of qualitatively preferable activities remains unclear. Moreover, Mill's distinction seems to be rather conventional and based on a particular notion of high culture at the time.

Also in the writing "On Liberty" John Stuart Mill set different accents than his father's friend and teacher, Bentham. Whereas in a pure utility calculus freedom cannot be a value in itself, Mill here attaches a fundamental value to freedom and especially to freedom of speech. In order to discern truth, all relevant arguments must be examined. However, this is impossible if opinions and arguments are politically suppressed. The correct determination of the greatest happiness thus presupposes freedom of expression (freedom of the press, freedom of science, etc.).

This libertarian version of utilitarianism is also found in the political philosophy of Bertrand Russell (1872-1970).

Later forms

The classical utilitarianism of Bentham and Mill influenced many other philosophers and led to the development of a broader concept of consequentialism. The hedonistic utilitarianism of Bentham and Mill, although best known, is now held by only a minority. More advanced variants of utilitarianism, improved in the face of criticism, were developed by William Godwin (1756-1836), a contemporary of Bentham with anarchist tendencies, and Henry Sidgwick (1838-1900), among others. In more recent times, the most notable are Richard Mervyn Hare (1919-2002), Richard Brandt (1910-1997), who coined the term "rule utilitarianism", John Jamieson Carswell Smart, and Peter Singer, who was long a proponent of preference utilitarianism, but for some years has advocated the classical, hedonistic variant of utilitarianism. Ludwig von Mises argued for liberalism using utilitarian arguments. Conversely, some philosophers advocated ethical socialism on a utilitarian basis.

As the examples show, utilitarianism is mainly widespread in the English-speaking world. One of the few German representatives is the philosopher Dieter Birnbacher from Düsseldorf, who has also emerged as a translator of John Stuart Mill.

Jeremy Bentham

Theoretical contents

Basic principles

Utilitarianism is based on some core principles that set it apart from other normative theories. Once one gets away from the core principles, one finds a set of assumptions that are shared by many, but not all, utilitarians. Particularly in the 20th century, a number of sub-currents in utilitarianism have emerged that reject assumptions of classical utilitarianism. This is why many modern philosophers prefer the collective term "consequentialism" for their view.

Three basic principles characterize utilitarianism:

- Value objectivity and neutrality: The yardstick for judging consequences is their objective value, in utilitarianism in particular their utility. What matters here is not the utility for arbitrary goals, purposes or values - utilitarianism is not value-nihilistic - but rather the utility for the good per se. Virtually all utilitarians also assume that the value of consequences can be assessed independently of observers and agents: if different agents and observers are fully rational and morally enlightened, they should treat equal consequences equally. Utilitarians are also value monists: they believe that all morally interesting values can be reduced or converted to one value, utility or happiness.

- Eudaemonism: The only good of utilitarianism is happiness or, more generally, human well-being. There are different opinions about what exactly is meant by human well-being. The classical utilitarians Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill were hedonists. According to hedonism, human well-being consists in the sensation of pleasure and joy, and the absence of suffering and pain. Modern utilitarians are not necessarily hedonists, however, and a wide range of views exists. Preference utilitarianism is guided by economic ideas about utility, according to which human well-being is understood as the satisfaction of preferences. Both views have in common that they have a subjective understanding of well-being; but in fact utilitarianism is also compatible with an objective notion of well-being, according to which well-being is the experience of objectively valuable experiences.

- Universalism: Utilitarianism is universalistic, since the well-being of each individual has equal weight in its considerations. It is not the happiness of the acting person alone that matters, nor the happiness of a group, society, or culture, but the happiness of all those affected by an action. Thus utilitarianism is not a selfish ethic, but rather a considerate one: the collective good is superior to the individual good. Universalism contradicts intuitive judgments according to which, for example, the lives of close people are more important than the lives of strangers. Utilitarianism is also universalistic in that its ethics apply equally to all individuals. Hypothetically, though not necessarily practically, there are no notions of particular responsibilities here.

When these three basic principles are taken together, the basic utilitarian formula emerges: An action is morally right if, and precisely if, its consequences are optimal for the welfare of all those affected by the action.

General features

In addition to the above three basic principles, there are a number of features that are shared by almost all utilitarians but rejected by a few utilitarians. These features are thus not obligatory characteristics of utilitarian ethics, even though they are often presented as such.

- Consequentialism: In utilitarianism as a teleological ethics, the rightness of an action is basically not derived from itself or its properties, but from its consequences. In order to evaluate an action morally, one must determine and evaluate the consequences of the action. The rightness of an action then results from the value of its consequences. Other questions, such as whether an action is done out of good will or not, are of secondary or no interest here. At the same time, the consequence principle implies an empiricist approach.

- Maximization. All classical utilitarians, and almost all modern utilitarians, assume that an action is right precisely if it maximizes welfare. But this assumption leads to some counterintuitive results. Many everyday actions - going to the movies, for example - do not maximize the welfare of others, and so would have to be judged morally wrong according to the basic utilitarian formula. Some utilitarians have therefore modified the position so that an action is right if it leads to sufficiently good, rather than maximally good, outcomes.

- Aggregation. Another assumption, increasingly rejected by modern utilitarians, is that the distribution of utility between individuals does not count. In classical utilitarianism, utility is simply aggregated, so that no distinction is made between a distribution in which 100 utilities accrue to a given individual and 99 individuals accrue none, and a distribution in which one hundred individuals each perceive a "utility point." However, some utilitarians reject this assumption. According to moral prioritarianism, the marginal utility that accrues to well-off individuals has less moral value than the marginal utility of worse-off individuals. (This position is not to be confused with the assumption of diminishing marginal utility). Such a position rejects the assumption of simple aggregation.

- Action focus. Most utilitarian ethics focus on the rightness of individual actions, but other alternatives are possible. The best-known alternative, sometimes attributed to Mill, is so-called rule utilitarianism, according to which an action is right if it conforms to a rule whose general observance maximizes utility. More recent research has questioned whether utilitarians should choose a "focal point" at all - utilitarians should prefer the actions, rules, character forms, etc. that maximize utility in each case. This "fokeless" position is usually referred to as global utilitarianism.

- Binary Action Evaluation. Standard forms of utilitarianism specify when an action - or rule, etc. - is right. These forms of utilitarianism thus accept the classical evaluation system of normative ethics, according to which actions are divided into "right" and "wrong", or "permitted" and "unpermitted". So-called scalar utilitarianism, on the other hand, rejects this assumption.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is utilitarianism?

A: Utilitarianism is the view that the right thing to do is whatever is most useful. It is a philosophical position about ethics.

Q: Where does the word "utilitarianism" come from?

A: The word "utilitarianism" comes from the word "utility", which means "usefulness".

Q: What are things that increase human well-being or happiness called in utilitarianism?

A: In most forms of utilitarianism, things that increase human well-being or happiness are called useful.

Q: Does this include only the happiness caused by a single action?

A: No, this includes not only the happiness caused by a single action but also includes the happiness of all people involved and all future consequences.

Q: What is the general theory of utilitarianism?

A: The general theory of utilitarianism is that whatever brings the most happiness to the greatest number of people is the right thing to do.

Q: Is it possible for something to be both ethical and unethical according to utilitarianism?

A: Yes, depending on how it affects different groups of people, something can be both ethical and unethical according to utilitarianism.

Search within the encyclopedia