Ulrich Beck

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Ulrich Beck (disambiguation).

Ulrich Beck (* 15 May 1944 in Stolp; † 1 January 2015 in Munich) was a German sociologist. Beck became known far beyond the boundaries of his field with his book title Risk Society, published in 1986 and translated into 35 languages. On the way to a different modernity. In it, he described, among other things, the "de-traditionalization of the forms of life in industrial society", the "de-standardization of gainful employment", and the individualization of life situations and biographical patterns. Beck criticized sociological approaches that remained stuck in nation-state aspects and terminology. He saw the technical-economic progress within the framework of industrial society - for example, in the use of nuclear power - as being overlaid and called into question by unplanned side-effects of supranational and partly global proportions. Increasingly, the manifestations and consequences of transboundary environmental problems and globalization were the points of reference for his theorizing.

Beck was Professor of Sociology at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, at the London School of Economics and Political Science and at the FMSH (Fondation Maison des Sciences de l'Homme) in Paris. In 2012, the European Research Council granted him a five-year project on "Methodological Cosmopolitanism as Exemplified by Climate Change". Ulrich Beck's research and theory-building has been associated with a wide range of active political engagement. In the aftermath of the financial crisis from 2007 onwards, which led to a sovereign debt crisis in the euro area, he wrote the manifesto "We are Europe!" together with the Green politician Daniel Cohn-Bendit in 2012, which propagated a Voluntary European Year for all age groups with the aim of re-founding Europe in the active cooperation of its citizens "from below".

Ulrich Beck (2012)

Live

Ulrich Beck grew up in Hanover. After graduating from high school, he first began studying law in Freiburg im Breisgau. He later received a scholarship from the German National Academic Foundation and studied sociology, philosophy, psychology and political science at the University of Munich. There he received his doctorate in 1972 and seven years later his habilitation in sociology. Ulrich Beck was married to the family sociologist Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim.

Beck held professorships at the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster from 1979 to 1981 and in Bamberg from 1981 to 1992. For many years he was a member of the convention and board of the German Sociological Association. From 1999 to 2009, Ulrich Beck was spokesman of the Collaborative Research Center 536: "Reflexive Modernization", an interdisciplinary cooperation between four universities in the Munich area, which was financed and reviewed by the German Research Foundation (DFG). Here, Beck's theory of reflexive modernization was empirically tested in an interdisciplinary manner on the basis of a broad range of topics in corresponding research projects.

Beck was a member of the Board of Trustees at the Jewish Center Munich and of the German PEN. In March 2011, he became a member of the Ethics Commission for Secure Energy Supply.

Ulrich Beck died on 1 January 2015 at the age of 70 as a result of a heart attack. He is buried in Munich's North Cemetery.

Beck (2011) on the Blue Sofa

Factory

Following his successful publication "Risk Society" in 1986, Ulrich Beck published a large number of further articles over the next 25 years on the question that determined his research: How can social and political thought and action be opened up to a historically and newly interwoven modernity in the face of radical global change (environmental destruction, financial crisis, global warming, crisis of democracy and nation-state institutions)?

The subject of Beck's research, publications and political initiatives was mainly transnational and global sociological contexts. He paid particular attention to the opportunities and problems of European integration, to globalization trends and challenges, and to the prospects of a world domestic policy.

Debordered risk society

In the year of publication of Ulrich Beck's study Risk Society. On the Way to a Different Modernity, the nuclear catastrophe of Chernobyl occurred on 26 April, to which Beck referred right at the beginning: "Much of what was still fought for argumentatively in writing - the imperceptibility of the dangers, their dependence on knowledge, their supranationality, the "ecological expropriation", the transformation of normality into absurdity, etc. - reads after Chernobyl like a flat description of the present". At the end of the 20th century, nature, brought into the industrial system in the course of techno-industrial transformation and worldwide marketing, turns out to be one that has been used up and contaminated. "Hazards become stowaways of normal consumption. They travel with the wind and with the water, are in everything and everyone, and pass through all the otherwise tightly controlled protective zones of modernity with the most essentials of life - the air we breathe, our food, our clothing, our home furnishings." This, he said, was the end of the classical industrial society that the 19th century had produced, and of conventional notions of, among other things, nation-state sovereignty, automaticity of progress, classes, or the merit principle.

A distinctive feature of the risk society compared to the uncertainties, threats and catastrophes of earlier eras - which were attributed to the forces of nature, gods or demons - is the fact that ecological, chemical or genetic hazards are caused by decisions made by human beings: "When the Lisbon earthquake struck in 1755, the world groaned. But the Enlightenment thinkers cited not industrialists, engineers, and politicians, as they did after the nuclear reactor disaster at Chernobyl, but God in man's court." Beck notes that technologists nowadays have a green light to turn the world upside down, even to push for "constitutional changes of life" that entered unlegitimized with human genetics. "You just wonder sometime later that the family, much like the dinosaurs and the cockchafer, no longer exists." The "brave new world" could become reality "if and because the cultural horizon has been broken and stripped away, in which it still appears as a 'brave new world' and can be criticized."

Beck clearly distinguishes between risk and catastrophe. Accordingly, risk includes the anticipation of future catastrophes in the present. This results in the goal and possibilities of disaster avoidance, for example with the help of probability calculations, insurance regulations and prevention. Long before the financial crisis erupted worldwide in 2008, Beck predicted: the new risks that set in motion a global anticipation of global catastrophes are shaking the institutional and political foundations of modern societies (see most recently the worldwide controversy over the risks of nuclear energy after the reactor disaster at Fukushima). The new type of global risks, he argues, is characterized by four features: Dissolution of boundaries, uncontrollability, non-compensability and (more or less unacknowledged) ignorance. But because global risks are partly based on non-knowledge, the lines of conflict of the global risk society are culturally determined. According to Beck, we are dealing with a clash of risk cultures.

Ulrich Beck's "Risk Society" was named one of the 20 most important sociological works of the century by the International Sociological Association (ISA).

Reflexive modernization

The theory of reflexive modernization (see also the distinction between First and Second Modernity) elaborates the basic idea that the triumphant march of industrial modernity across the globe produces side-effects that question the institutional foundations and coordinates of nation-state modernity, change them, open them up for political action. For Beck, this is essentially the self-confrontation of the consequences of modernization with the foundations of modernization:

"The constellations of the risk society are generated because the self-evident features of industrial society (the consensus on progress, the abstraction of ecological consequences and dangers, control optimism) dominate the thinking and actions of people and institutions. The risk society is not an option that can be chosen or rejected in the course of political debates. It emerges in the self-running of independent, consequence-blind, danger-defying modernisation processes. These produce, in sum and latency, self-endangerments that question, annul, change the foundations of industrial society."

According to Beck, reflexive modernisation goes hand in hand with forms of individualisation of social inequality. The cultural preconditions of social classes dwindle, with a sharpening of social inequality occurring "which now no longer runs in major situations identifiable throughout life, but becomes fragmented (in terms of) time, space, and society." Wolfgang Bonß and Christoph Lau see reflexive modernization as a process of fundamental change in which the old realities and approaches to solutions persist alongside new others. The old form of the nuclear family was joined by various new forms; alongside the classic form of the Fordist company, new forms of network organization were established; new, more flexible forms of work were added to the classic "normal employment relationship"; and alongside the traditional forms of disciplinary basic research, various forms of transdisciplinary research were now emerging. "It is precisely this simultaneity of old and new that makes it so difficult to diagnose the change clearly or even to describe it as a clear break."

Beck's theory of reflexive modernization aims at overarching interactions and connections, also in terms of scientific theory. As it says in Risikogesellschaft:

"Rationality and irrationality are never just a question of the present and the past, but also of the possible future. We can learn from our mistakes - which also means: another science is always possible. Not just a different theory, but a different epistemology, a different relationship between the theory and practice of that relationship."

Beyond sociology, Beck advocated not remaining stuck in conventional research approaches and theories. For example, he criticized a lack of concern in historiography for "a theoretically comprehensive examination of the basic questions of historiography" and pleaded for historical change to be researched in the light of appropriate sociological theoretical aspects as well. He was prompted to do so by Benjamin Steiner's study Nebenfolgen in der Geschichte. Eine historische Soziologie reflexiver Modernisierung, for which Beck wrote the foreword. Steiner himself, after exemplifying his theme of historical collateral consequences in four objects of study ranging from Attic democracy to the crisis of historicism, concludes, "The role that unintended collateral consequences play in history should also be more widely recognized for the reason that our time needs more than ever an understanding of the deeper structures that underlie historical events."

Sub Policy

Reflexive modernization that encounters the conditions of "highly developed democracy and enforced scientificity," according to Ulrich Beck already in 1986 in Risk Society, "leads to characteristic delimitations of science and politics. Monopolies of knowledge and change become differentiated, migrate from their designated places, and become generally available in a certain, changeable sense." In the Second Modernity, the sciences would no longer be considered only for problem solving, but also as problem causers; for scientific solutions and promises of liberation had meanwhile revealed their questionable sides in the course of practical implementation. This and the unmanageable flood of dubious, incoherent detailed results resulting from the differentiation of science produced an uncertainty also in external relations; thus addressees and users of scientific results in politics, economy and the public became "active co-producers in the social process of knowledge definition" - a development of "high-grade ambivalence":

"It contains the chance of emancipation of social practice from science by science; on the other hand, it immunizes socially valid ideologies and standpoints of interest against scientific enlightenment claims and opens the door to a feudalization of scientific knowledge practice by economic-political interests and "new powers of belief.""

In the sense of reflexive scientification and sub-political control, Beck relied, among other things, on institutionally secured counter-expertise and alternative professional practice.

"Only where medicine stands against medicine, atomic physics against atomic physics, human genetics against human genetics, information technology against information technology, can it become possible to overlook and judge from the outside which future is here in the retort. Enabling self-criticism in all forms is not a threat, but probably the only way in which the error that will otherwise cause the world to blow up in our faces sooner or even sooner could be discovered in advance."

For the future of democracy, however, it is a question of whether the citizenry depends on the judgement of experts and counter-experts "in all details of questions of survival" or whether the culturally produced perceptibility of dangers enables us to regain the individual competence to judge.

Since the 1980s, according to Beck, important political issues have been set by citizens' initiatives - against the resistance of the established parties in the West, against the informer and surveillance apparatus of state power through the forms of resistance and street demonstrations in Eastern Europe at the time. He describes such approaches and forms of shaping society from below as sub-politics. One of their characteristics is the direct, selective participation of citizens in political decisions, bypassing parties and parliaments as the institutions of representative decision-making. Economy, science, profession and private everyday life are thus caught up in the storms of political debate. Beck counts mass boycott movements, including transnational ones, among the particularly conspicuous and effective means of sub-politics.

Individualization

Individualisation in Ulrich Beck's sense does not mean individualism, nor emancipation, autonomy, individuation (becoming a person). Rather, it is about processes of firstly the dissolution, secondly the replacement of industrial social forms of life (class, stratum, gender relations, normal family, lifelong occupation), caused, among other things, by institutional change in the form of basic social and political rights addressed to the individual, in the form of changed training courses and extensive mobility of work. The result is a situation in which individuals have to produce, stage and cobble together their own biographies. According to Beck, the "normal biography" becomes a "biography of choice", a "biography of tinkering", a "biography of rupture". People are - following Sartre - condemned to individualisation. This development is not only taking place in the classic industrial countries, but also affects China, Japan and South Korea, for example, with a time lag and in other forms.

Cosmopolitanism

The second modernity, according to one of Beck's core theses, abolishes its own foundations. Basic institutions such as the nation state and the traditional family are being globalized from within. For him, a serious alignment deficit in research and practice is the methodological nationalism of political thought, sociology and other social sciences.

Methodological nationalism means that the social sciences are prisoners of the nation state in their thinking and research. They define society and politics in national terms, they choose the nation-state as the unit of their research, as if this were the most natural thing in the world. All their key concepts (democracy, class, family, culture, domination, politics, etc.) are based, according to Beck, on basic nation-state assumptions. This may have been historically appropriate in the Europe of the 19th and 20th centuries, but it is becoming increasingly false in the era of globalization and world risk society, because transnational dependencies and interdependencies, global risks in fact, penetrate almost all problems and phenomena from within and change them profoundly. Methodological nationalism, however, blinds us to this global change that is taking place in national societies.

This is why Beck has been designing a cosmopolitan sociology since 2000, in order to ground sociology as a science of reality in the 21st century. For only in this way would the social sciences be able to observe global change at all, which was not taking place "out there" but "in here" - in families, households, love relationships, organizations, professions, schools, social classes, communities, religious communities, nation states.

Cosmopolitanism means the change from a form of society that is essentially shaped by the nation-state in politics, culture, economy, family and labour market, to a form of society in which nation-states globalise from within (internet and social networks; export of jobs; migration; global problems that can no longer be solved nationally). According to Beck, this does not mean cosmopolitanism in the classical sense, no normative call for a "world without borders". Rather, in his view, major risks generate a new cross-national compulsory community, because the survival of all depends on their coming together to act together.

Cosmopolitanism is about norms, cosmopolitanism about facts. Cosmopolitanism in the philosophical sense, in Immanuel Kant as in Jürgen Habermas, involves a world political task assigned to the elite and enforced from above, or from below through civil society movements. Cosmopolitanization, on the other hand, takes place from below and from within, in everyday events, often unintentionally, unnoticed, even if national flags continue to be waved, the national guiding culture is proclaimed, and the death of multiculturalism is proclaimed. Cosmopolitanism means the erosion of clear boundaries that once separated markets, states, civilizations, cultures, lifeworlds and people; it means the existential, global entanglements and confrontations that arise as a result, but also encounters with the Other in our own lives.

Beck's social scientific cosmopolitanism aims at three components: an empirical research perspective, a social reality, and a normative theory. Taken together, these three aspects make social scientific cosmopolitanism the critical theory of our time by challenging the traditional truths that govern thought and action today: the national truths. Beck has tested, reviewed, and developed, often in co-authorship with others, the empirical content of his theory of sociological cosmopolitanism on the following topics or phenomenon: Power and Domination, Europe, Religion, Social Inequality, and Love and Family.

Europe in theory and practice

In 2004, the year of the eastward enlargement of the European Union, Ulrich Beck, together with Edgar Grande, presented the book Das kosmopolitische Europa (Cosmopolitan Europe). In it, model concepts and scenarios of a European future under the sign of reflexive modernization are developed. The cosmopolitan and the national are not mutually exclusive opposites.

"Rather, the cosmopolitan must be conceived, unfolded, and empirically studied as an integral of the national. In other words, the cosmopolitan transforms and preserves, it opens up the history, present and future of individual national societies and the relationship of national societies to one another."

The formula of a cosmopolitan Europe should be understood as a theoretical construct and political vision in one. In this context, nationality, transnationality and supranationality complement each other positively to form a "both/and". In the sense of a new critical theory of European integration, it is important to move away from an internally fixed design of European integration, which has been based on playing up non-European threat or challenge scenarios in order to neutralize resistance at the nation-state level to progress in European integration. Moreover, on the basis of a cosmopolitan Europe, multiple cosmopolitanisms could be fostered. Ultimately, it is a matter of organizing contradictions and ambivalences; "these have to be endured and politically fought out, they cannot be resolved."

For Beck and Grande, momentum and secondary consequences as constitutive features of reflexive modernity are also evident in the only conditionally controllable further development of Europe, which is based on a "Doing Europe". The spirit of contemporary European action arises from the remembered view into the abysses of European civilization. Doing Europe is the never again in action.

"Cosmopolitan Europe is the self-critical experimental Europe rooted in its history, breaking with its history and gaining the strength for it from its history."

According to the authors, a European civil society and a cosmopolitan Europe can only be imagined in solidarity. It is necessary to change the self-image of all groups involved in the sense of a cosmopolitan common sense in the direction of a European social consciousness that favours a positive attitude towards the otherness of others.

Beck and Grande see the nationalization of European politics, which has dominated since the founding of the European Communities and which has disenfranchised European citizens, as a serious undesirable development that needs to be addressed. As an antidote to the existing institutions of parliamentary democracy, they recommend the introduction of independent opportunities for citizens to articulate and intervene, especially in the form of Europe-wide referendums on every issue, initiated by a qualified number of European citizens, with binding effect for the supranational institutions.

In its external relations, Europe should advance the principle of regional cosmopolitanism in line with its own model and promote regional alliances of states with the involvement of non-state global actors such as NGOs. In doing so, a one-sided orientation should be avoided, and alternative development paths of modernity should be accepted. Nor should it remain a matter of development policy handouts; rather, European markets should be opened up to the products and initiatives of others in a spirit of partnership.

In 2010, Ulrich Beck and Angelika Poferl examined the situation in the EU with a view to the growing social inequality that is prevalent at the beginning of the 21st century, which is the result of increasing wealth on the one hand and increasing poverty on the other, both globally and in many cases nationally. They use Max Weber's distinction between social inequality, which may be very drastic but is accepted as legitimate, and inequality that becomes a political problem. Thus national inequality is legitimized by the achievement principle, global inequality by the nation-state principle (in the form of "institutionalized looking the other way"). But the more barriers and borders are dismantled within the EU and norms of equality are enforced, the more persistent or newly emerging inequalities become a political issue, as the euro crisis makes strikingly clear:

"One only has to think of the contrasts between deficit and surplus countries, the risk of national bankruptcy, which on the one hand affects certain countries, and on the other endangers the Eurozone as a whole; but also of the efforts to find European political answers, which not only incite the governments of the "empty coffers" against each other, but awaken nationalist atavisms in the populations. In this way, new relations of inequality and domination between countries and states within the EU are created. [...] The riots that ignite from this are an example of how it becomes clear: in the experiential horizon of European inequality dynamics, a tremendous rage has built up that could lead to the destabilization of individual countries or even the EU."

In September 2010, Ulrich Beck was involved in the founding of the Spinelli Group, which advocates European federalism. In the We are Europe! manifesto for the re-foundation of the EU from below, written together with Daniel-Cohn Bendit. Manifesto for the Re-foundation of the EU from Below, he advocated in 2012, among other things, the creation of a European Voluntary Year. The background to the initiative, which was addressed not only to the EU institutions in Brussels, but also to the national parliaments and the citizens of the Union, was the rampant youth unemployment in the southern European countries and the widening gap between poverty and wealth.

Political position-taking

In terms of economic policy, Beck pleaded for new priorities to be set. Full employment was no longer achievable in view of automation and the flexibilisation of gainful employment, national solutions were unrealistic, "neoliberal medicine" was not working. Instead, the state would have to guarantee an unconditional basic income and thus make more citizen work possible. Such a solution would only be feasible if uniform economic and social standards applied at the European level or - in the best case - at various transnational levels. Only in this way would it be possible to control transnationally active companies. In order to contain the power of transnational corporations (TNCs), he therefore advocates the establishment of transnational states as a counterbalance. This would also make it possible to implement a financial transaction tax, which would open up room for manoeuvre for a social and ecological Europe.

On the legal level, Beck was of the opinion that without the development and expansion of international law and corresponding judicial instances, the settlement of transnational conflicts by peaceful means would be impossible. For this he coined the term legal pacifism.

Beck has continuously published articles in major European newspapers: Der Spiegel, Die Zeit, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Frankfurter Rundschau, La Repubblica, El País, LeMonde, The Guardian and others. As a member of the German government's Ethics Commission for a Secure Energy Supply, Beck warned in 2011 that catastrophes like the one in Fukushima could lead to an erosion of the understanding of democracy: "By agreeing to nuclear energy, politicians have bound themselves to the fate of this technology. With the occurrence of the unimaginable, citizens' trust in politicians is lost."

Means of representation

Driven by "his encyclopaedic education and an almost inexhaustible wealth of interests", Beck's sociological and political publications have often taken the form of the major essay. In them Beck repeatedly succeeded in developing catchy short formulas for social facts and developments. Thus he coined numerous terms, among them: Risk society, reflexive modernization, elevator effect, methodological nationalism, sociological cosmopolitanism, individualization, deinstitutionalization, de-traditionalization, and, in relation to globalization, the terms second modernity, globalism, globalism, Brazilianization, as well as transnational state and cosmopolitan Europe. The use of language was a particular issue for Beck. "Sociology, which is situated in the container of the nation-state, and has developed its self-understanding, its forms of perception, its concepts within this horizon, comes methodologically under suspicion of working with zombie categories. Zombie categories are living-dead categories that haunt our minds, adjusting our vision to realities that are increasingly disappearing." In contrast, Beck set out to find a new language of observation in the social sciences for a globalized world.

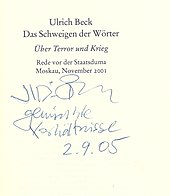

Autograph

Search within the encyclopedia