Ulm

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Ulm (disambiguation).

Ulm (![]()

![]() [ʊlm]) is a university city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, located on the Danube River at the southeastern edge of the Swabian Jura on the border with Bavaria. The city has over 125,000 inhabitants (as of the end of 2019), forms its own urban district and is the seat of the district administration of the adjacent Alb-Donau district. According to the state development plan of Baden-Württemberg, Ulm is one of a total of 14 regional centres in the state and forms with Neu-Ulm one of the cross-state dual centres of Germany with 183,323 inhabitants. Ulm is the largest city in the administrative district of Tübingen and in the Donau-Iller region, which also includes areas of the Bavarian administrative district of Swabia.

[ʊlm]) is a university city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, located on the Danube River at the southeastern edge of the Swabian Jura on the border with Bavaria. The city has over 125,000 inhabitants (as of the end of 2019), forms its own urban district and is the seat of the district administration of the adjacent Alb-Donau district. According to the state development plan of Baden-Württemberg, Ulm is one of a total of 14 regional centres in the state and forms with Neu-Ulm one of the cross-state dual centres of Germany with 183,323 inhabitants. Ulm is the largest city in the administrative district of Tübingen and in the Donau-Iller region, which also includes areas of the Bavarian administrative district of Swabia.

The city is known for its Gothic cathedral, whose steeple of 161.53 meters is the highest in the world. Furthermore, Ulm's long civic tradition is remarkable, with the oldest constitution of a German city and a municipal theatre whose beginnings date back to 1641. In the past, Ulm was the starting point for the emigration of the Danube Swabians, who travelled to their new homelands in south-eastern Europe on so-called Ulm boxes.

Ulm, first mentioned in a document on July 22, 854, was a royal palatinate and free imperial city, from 1802 Bavarian, has been Württemberg since 1810. Since then Ulm has been separated from its former territory on the right bank of the Danube, which remained with Bavaria and on which the city of Neu-Ulm developed.

Famous personalities include Albert Einstein (1879-1955), who was born in Ulm, the resistance fighters Hans (1918-1943) and Sophie Scholl (1921-1943), who grew up in Ulm from 1932, as well as the actress Hildegard Knef (1925-2002), who was born in Ulm, and the German designer and graphic designer Otl Aicher (1922-1991), who was born and grew up in Ulm.

View of Ulm: Neutorbrücke with the Ulm Cathedral .

View of the old town from the right bank of the Danube

Geography

Geographical position

The city of Ulm lies at an average altitude of 479 m above sea level (measuring point: city hall). The city area is geographically richly structured and ranges from 459 m above sea level (Danube bank) to 646 m above sea level (Klingensteiner Wald). The historic city center is located about two kilometers below (east of) the confluence of the Iller River at the mouth of the Blau into the Danube. The town lies on the southern edge of the Ulmer Alb (part of the middle Flächenalb) and the plateau of the so-called "Hochsträß", which is separated from it to the south by the former valley of the Urdonau (Blau-, Ach- and Schmiechtal). The elevations of Hochsträß and Alb (from west over north to east: Galgenberg, Kuhberg, Roter Berg (Hochsträß), Eselsberg, Kienlesberg, Michelsberg, Safranberg (Ulmer Alb)), separated from each other by smaller or larger valleys, surround the city centre in the west, north and east. In the south, this is limited by the course of the Danube.

The urban area of Ulm extends for the most part north of the Danube, which here for a few kilometres forms the state border between the federal states of Baden-Württemberg and Bavaria with the Bavarian sister city of Neu-Ulm, located on the southern bank of the Danube. In the west and north, the city area extends with the suburbs Harthausen, Grimmelfingen, Einsingen, Ermingen, Allewind and Eggingen over the plateaus of the Hochsträß, with Lehr, Mähringen and Jungingen over the plateaus of the Ulmer Alb. To the west of the city centre lies the suburb Söflingen south of the Blau on the edge of the Hochsträß. The suburb of Böfingen adjoins the city centre to the northeast and lies on the slopes of the Alb north of the Danube. Only above the confluence of the Iller with the Danube does Ulm's urban area, including the districts of Wiblingen, Gögglingen, Donaustetten and Unterweiler, extend to the floodplains and alluvial terraces of the Danube and Iller to the southwest of the Danube and Iller.

Floor space allocation

According to data from the State Statistical Office, as of 2015.

Historical geography

Significant Palaeolithic finds have been found in the area around Ulm, for example in the neighbouring town of Blaubeuren and a few kilometres north of Ulm in the Lone Valley (e.g. in the Vogelherdhöhle cave). They indicate that the area at the edge of the Alb offered an interesting habitat in the times of hunter-gatherers. In the Neolithic period the Hochsträß was settled early (e.g. Ulm-Eggingen); from Ulm itself there are finds from a younger phase of the Neolithic. The course of the Danube and Iller rivers and the easy crossing of the Swabian Alb between Ulm and Geislingen through the river valleys of Blau, Kleiner Lauter, Lone, Brenz, Kocher and Fils, which cut far into the Alb plateau from the south and north, played a role in the development of the city of Ulm as a traffic hub that should not be underestimated.

The Roman road not far from the southern bank of the Danube near Ulm between the Roman fort of Unterkirchberg, the small fort of Burlafingen and the small fort of Nersingen. The Roman road running not far from the southern bank of the Danube near Ulm between the Roman fort of Unterkirchberg, the small fort of Burlafingen and the small fort of Nersingen, which today is called the Donausüdstraße by historians, the Roman road branching off to the north into the Filstal valley to the fort of Urspring (fort Ad Lunam) and the dense evidence of Roman sites and estates in the Ulm area make the strategically important position of the Ulm area in the hinterland of the militarised borderline of the Limes recognisable until the fall of the Limes around the year 260 AD. From 15 B.C. until about 100 A.D. and then again after the fall of the Limes from 260 A.D. until about 500 A.D. (Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes), the bank of the Danube opposite Ulm formed the northern border of the Roman Empire. The state border between Bavaria and Württemberg runs in the Ulm area exactly where the border between the Imperium Romanum and unoccupied Germania (Germania Magna) ran more than 2000 years ago.

The burials of the large burial ground from the Merovingian period on the Kienlesberg (directly northwest of the city centre), dating from the 6th and 7th centuries and partly furnished with imported goods from the Baltic and Mediterranean regions, as well as the early medieval royal palace of the Carolingians on the Weinhof and in the area of the Hl. Geist Spital (first mentioned in a document in 854) underline Ulm's special importance as a strategically significant traffic junction during the early Middle Ages.

Due to its location at the junction of several trade and pilgrimage routes by land and sea, Ulm developed into a leading trade and art centre in southern Germany during the High and Late Middle Ages as a Free Imperial City. In the late Middle Ages, Ulm merchants maintained a dense network of trade contacts that stretched from Scandinavia to North Africa, from Syria to Ireland and beyond. One of the important pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela to the grave of St. James, venerated by the Catholic Church, the Way of St. James, led through Ulm to north-west Spain and has been promoted by the city of Ulm and the state of Baden-Württemberg since 1997 as a way of uniting people in the sense of European unification. As the Franconian-Swabian Way of St. James, it runs from the north to the cathedral and from there, as the Upper Swabian Way of St. James, it continues well marked south to Switzerland.

From the late 17th century onwards, Ulm became the central collection point for mostly (but not always) Swabian emigrants who were settled in the newly conquered territories of the Habsburg and Russian empires in southeastern Europe and southern Russia. A first wave of emigrants reached the newly conquered lands of the Habsburg Empire in southeastern Europe on Ulm boxes between the late 17th and mid-18th centuries. In their new settlement areas in present-day Romania, Hungary and Serbia, the ethnic groups of the Hungarian Germans and/or Danube Swabians emerged.

A second wave of emigration followed at the beginning of the 19th century. From 1804 to 1818, thousands of emigrants travelled by water to the mouth of the Danube (Dobruja) in today's Bulgaria and Romania as well as to Bessarabia (today's Republic of Moldova) on the northern Black Sea (today's southern Ukraine) and from there to southern Russia, especially to the Caucasus region. The emigrants, most of them of Swabian origin, embarked in Ulm on rafts and Ulm boxes and travelled down the Danube to its mouth in the Black Sea at Ismajil. Travel stories tell of the emigrants' great hardships during the 2,500-kilometre journey. Numerous accidents and diseases, which broke out after drinking polluted river water and due to the worst hygienic conditions in the crowded confines of the mostly overcrowded boats, claimed countless lives. The result of this second great downstream emigration movement were the ethnic groups of the Dobruja Germans, Bessarabian Germans, Black Sea Germans, and Caucasian Germans.

Through these waves of emigration, the close contacts of Ulm merchant and shipowner families to this region, which already existed before this time, were sustainably strengthened. After the expulsion of the Hungarian Germans and Danube Swabians from Serbia and Hungary as a result of the Second World War, as well as a wave of emigration of Danube Swabians from Romania that began after 1990, they often settled in the former areas of origin of their ancestors. As a result, a strong Danube Swabian community has developed around Ulm since the late 1940s. Today, several monuments erected in the city area commemorating the history and expulsion of the Danube Swabians, the Danube Swabian Central Museum (DZM) opened in 2000 in the rooms of the Upper Danube Bastion (Federal Fortress Ulm) and numerous town twinning and cooperation projects with communities and towns along the Danube bear witness to Ulm's close ties with the Danube Swabians and Southeast Europe.

Ulm's wide-ranging intellectual and commercial connections, which have grown continuously since the Middle Ages, still play a central role in the consciousness of many Ulm residents today as the basis for present and future-oriented thought and action. They are very consciously cultivated as part of Ulm's own history and identity. The International Danube Festival, which has taken place every two years since 1998 with representatives of all Danube riparian states, the recently founded European Danube Academy, the "Living Stations of the Cross" of the large Italian community or an annual "French Wine Festival" underline the close mutual connections that have grown over centuries and are lived out in everyday life.

Neighboring communities

On the right (south-eastern) side of the Danube and Iller borders the Bavarian district town of Neu-Ulm. On the left (northwestern) side Ulm is almost completely surrounded by the Alb-Donau district. The neighboring municipalities of Baden-Württemberg are here (from south over west to north): Illerkirchberg, Staig, Hüttisheim, Erbach (Donau), Blaubeuren, Blaustein, Dornstadt, Beimerstetten and Langenau as well as in the east the Bavarian municipality Elchingen.

City breakdown

→ Main article: List of places in Ulm

The urban area of Ulm is divided into 17 districts: Stadtmitte, Böfingen, Donautal, Eggingen, Einsingen, Ermingen, Eselsberg, Gögglingen-Donaustetten, Grimmelfingen, Jungingen, Lehr, Mähringen, Oststadt, Söflingen, Unterweiler, Weststadt and Wiblingen. Nine districts, which were incorporated in the course of the most recent municipal reform in the 1970s (Eggingen, Einsingen, Ermingen, Gögglingen-Donaustetten, Jungingen, Lehr, Mähringen and Unterweiler), have their own local councils, which perform an important advisory function for the city council as a whole on matters concerning the districts. However, final decisions on measures can only be made by the city council of the entire city of Ulm.

Climate

With an average temperature of 8.4 degrees Celsius (°C) and an average precipitation of 749 millimetres (mm) per year, Ulm - like almost all of Germany - is located in the temperate climate zone. Compared to other cities in Baden-Württemberg, however, the climate in Ulm is relatively cold. The average temperature is significantly below the values of other places in the southwest (for example Heidelberg 11.4 °C, Stuttgart 11.3 °C). The average precipitation, on the other hand, hardly deviates from that usual in Baden-Württemberg (Heidelberg 745 mm, Stuttgart 664 mm).

Ulm is sometimes humorously referred to as the "capital of the foggy realm". However, the statistics of the German Weather Service show an average of 1659 hours of sunshine per year for Ulm, which is in the midfield of all recording weather stations. Until 2014, however, the relevant measuring station was located on the Kuhberg, one of the highest elevations in the city. In the meantime, it has been relocated to the Mähringen district, which is also at a higher elevation. Due to the elevated measurement locations, fog fields in the Danube valley, in which Ulm's city centre is located, were partially disregarded in the measurements.

Flooding is only occasionally a problem in Ulm. It usually only occurs when the Danube and the Iller carry a lot of melt or rain water at the same time. However, especially sudden melting weather has already led to severe flooding within half a day.

According to a study published in 2007, Ulm is "Germany's healthiest city". However, in addition to climate data, other criteria such as air pollution, medical care or the number of crèche places were also decisive for the assessment.

| Ulm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Climate data Ulm

Source: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Geology

In the Ulm area, the Tertiary, clastic molasse sediments border on the limestones of the Upper Jurassic. This is also accompanied by the landscape transition from the Alpine foothills to the Swabian Alb. The limestones of the Jurassic are overlaid by the sediments of the Alpine foothills (molasse sediments) to the south (and partly also to the north) of Ulm. In addition to the Quaternary deposits along the Blau-, Iller- and Donautal, sediments of the Brackwassermolasse ("Grimmelfinger und Kirchberger Schichten") of the Graupensandrinne, the Upper Marine Molasse, the Lower Freshwater Molasse ("Ulmer Schichten") as well as of the Upper Jurassic (mass limestones, cement marls of the Kimmeridgium) appear in Ulm. Quartz sands are mined, among others, near Eggingen (Ulm).

The Lower Miocene "Erminger Turritellenplatte" is located in the district of Ulm-Ermingen and is characterised by its fossil wealth. The deposit was formed about 18.5 million years ago (Lower Ottnangian) under shallow marine coastal conditions (Upper Marine Molasse).

In the thermal water borehole of Neu-Ulm (Donautherme Neu-Ulm), the Upper Jurassic (Malm) was drilled down to a depth of 460 m. The Upper Jurassic is followed by the Middle Jurassic (Dogger) and Lower Jurassic (Black Jura) layers. Below this follow the layers of the Middle Jurassic (Dogger) and the Lower Jurassic (Black Jurassic). From a depth of about 700 m to 890 m the layers of the Upper Triassic (Keuper) and up to about 1010 m of the Middle Triassic (Muschelkalk) appear. The crystalline bedrock, from which the thermal water is extracted, then finally follows below.

Nature

Nature reserves

→ Main article: List of nature reserves in Ulm

The city district of Ulm has 2 nature reserves:

- Gronne: 45.0 ha; since 15 December 1982

- Lichternsee: 92.0 ha; since 16 December 2014

According to the protected area statistics of the Baden-Württemberg State Institute for the Environment, Measurements and Nature Conservation (LUBW), 137.05 hectares of the city's territory are protected, or 1.15 percent.

Water protection areas

→ Main article: List of water protection areas in Ulm

Geotopes in the city district of Ulm

- Kesselbrunnen, Jungingen district, Tertiary period, Geotope ID ND8421001

- Abandoned quarry Steigäcker-Blattegert, district of Mähringen, Jurassic age, geotope ID ND8421002

- Abandoned quarry Hagener Tal, district Jungingen, geological age Jurassic, geotope ID ND8421003

- Hülbe St. Moritz, Jungingen district, Tertiary geological period, Geotope ID ND8421004

- Stockert, Ermingen district, Tertiary geological period, Geotope ID ND8421005

- Abandoned Eichhalde quarry, Mähringen district, Jurassic age, Geotope ID 8421001

- Käppelesberg sand pit, Eggingen district, Tertiary geological period, Geotope ID 8421002

Turritellen lime from the Erminger Turritellen plate

Drill shell limestone from the Upper Eselsberg near Ulm (Upper Marine Molasse)

Districts

History

Previous story

The oldest documented settlement in the Ulm area dates back to the early Neolithic period, around 5000 B.C. Evidence of settlements from this period can be found, for example, at Eggingen (excavations by the State Monuments Office of Baden-Württemberg) and Lehr (readings from various collectors).

Numerous excavations carried out since the 1960s in the context of urban archaeology (initially by the Stadtgeschichtliche Forschungsstelle, and most recently by the Landesdenkmalamt Baden-Württemberg) provide evidence of this: The area of the later Ulm was settled in the form of the villages "Westerlingen" and "Pfäfflingen", documented by deeds of donation from the Reichenau monastery, before it was first mentioned by name as "Ulm" (854). The oldest finds date from the end of the Neolithic period (burial of the Bell Beaker Culture on the Münsterplatz). As early as autumn 1857, a large, extremely richly furnished Alamannic burial ground of the Merovingian period was discovered north of the Ulm railway station on the Unterer Kienlesberg, which, despite inadequate excavation methods and find documentation, provided important clues for settlements on the Weinhof and in the area of the Grüner Hof (possibly: Westerlingen and Pfäfflingen), which were also of supra-regional importance.

As a result of the latest research by the State Monuments Office in Neue Straße, a complete rewriting of Ulm's city history up to the 14th century was recently outlined. The most important theses are: The palace was located at about the level of today's Spitalhofschule/Adlerbastei. The previously assumed location at the Weinhof is supposed to have been an Ottonian foundation. According to this, the core city goes back to an Ottonian city foundation.

Given the state of excavation and discussion to date, however, the arguments put forward are not entirely convincing, since the new model, which in some respects is very worthy of consideration, does less justice to the archaeological features in the rest of the city than the previous ideas on which the following chapters are based.

In May 2007, during excavation work at Salemer Hof in the southeast of Ulm's old town, remains of Neolithic settlement structures and a skeleton about 5000 years old were discovered.

Urban history

Ulm in the High Middle Ages (800 to 1200)

At the beginning of the High Middle Ages, probably around 850, Ulm became a royal palace. The first documentary mention dates from 22 July 854, when King Ludwig the German sealed a document in "Hulma". The name is a Germanic or pre-Germanic water name (Indo-Germanic root *uel: to turn, twist, roll or *el-/*ol-: to flow, stream, be wet, be musty), which points to a connection with the mouth of the Blau into the Danube.

However, there is also a new interpretation that goes back to the ford across the Danube further to the east, where the palace has been located since the new archaeological excavations:

"The associated centre of power, the focal point of this settlement, can be located further east, in the immediate vicinity of the former Danube ford in the area of the later medieval hospital. This area, which has hitherto received little archaeological attention, first became the focus of consideration in the course of our processing of the Neue Straße excavation results. The Indo-Germanic root of the place name, which explains Ulm with a surge of water or with the characteristics 'to turn, to wind, to roll' or 'to flow, to stream, to be damp and musty', confirms the original water location of the place. Here the ruling centre could control the crossing point of the long-distance roads and secure the Danube crossing, for which a ferry station can be assumed. Thus the economic function of the early seat of power clearly emerges, which can be connected in time with the palatinate Ulma mentioned in 854."

- Dumitrache/Legant (2006): The long road to the city.

Ulm was an important palatinate location for the next 50 years, which was reflected in the numerous royal visits. During the Hungarian storms, the palatinate was presumably converted into a refuge castle. Based on the excavations, the following further development is assumed:

"Since Ulm was located on royal or imperial property, only the king and, based on the dating information, only Otto I can be considered as the founder. Otto I must have recognized the strategic and central importance of Ulm on the Danube and, immediately after the victory in 955 over the Hungarians, which secured the imperial borders, initiated the founding of a city with a city castle on the outskirts. The area of the Ottonian city is identical with that of the Staufian city, a name introduced in the literature for the old city centre of Ulm. The associated castle was built on the site of what later became known as the Weinhof."

- Dumitrache/Legant (2006): The long road to the city.

Thus the Weinhof probably only became the site for a castle in Ottonian times. A tower, a Luginsland, was also built there later. It can be assumed that Otto I. probably took the first step towards the foundation of the city.

According to the latest findings of the archaeological investigations in the Neue Straße, Ulm's path from royal palatinate to free imperial city led through the following stages of development:

- Carolingian palace at the Danube crossing from the middle of the 9th century;

- Fortification and development into a refuge castle in the first half of the 10th century;

- Relocation of the seat of power from the lowlands to the ridge of the town in early Ottonian times - associated with the re-foundation of a castle with a town;

- Transition from timber to stone construction in Salian times;

- Reconstruction of the city destroyed in 1134 and expansion of the city in early baptist times;

- Internal growth and construction of the city wall over centuries connected with the development to the municipal city administration.

Ulm lost its importance as a place of royal sojourns during the time of the Saxon kings in the 10th and 11th centuries. It was not until the Salians - beginning with the court day of Conrad II in 1027 - that there is evidence of increased royal stays. In 1079 Frederick of Staufen was enfeoffed with the duchy of Swabia. After consolidating their power in this region, the Staufers were able to develop Ulm into one of their main bases. The extinction of the Salians led to fights over the imperial estates from this inheritance, as a result of which Ulm's surrounding area was burned down in 1131, and in 1134 the entire city was hit.

Under the Staufers, the Ulm Palatinate was rebuilt from 1140 and in its wake the settlement was further expanded. In 1174, a bridge over the Danube was mentioned in a document for the first time. In 1181 Ulm was raised to the status of a city and in 1184 became a Free Imperial City. About 100 years later Ulm seems to have been completely fortified, as it was able to withstand a siege by the counter-king Heinrich Raspe in the winter of 1246. Ulm developed into one of the main centres of power of the Staufer kings and emperors. Little is known about the constitutional development in Ulm's early phase. "A document on the elevation of Ulm to a city has not survived". The city development seems to have taken place in stages since the 11th century, without, however, leaving any written records. The granting of Esslingen's town charter by Rudolf von Habsburg in 1274 was probably more "an embarrassing solution to fill a [...] gap".

Ulm in the late Middle Ages (1200 to 1500)

With the end of the Hohenstaufen rule, Ulm succeeded in remaining a royal city, which was possibly due to the fact that the lines of the Counts of Dillingen holding the imperial bailiwick died out almost simultaneously and Count Ulrich of Württemberg as the new bailiwick holder had no ambitions regarding Ulm. At the end of the 13th century, a municipal bailiff is recorded who was elected annually by the citizens.

In the 14th century, the area of the town quadrupled to 66.5 hectares, which was to remain the size of the town until the 19th century. The expansion was accompanied by the refortification of the city, possibly in connection with an unsuccessful raid by Ludwig the Bavarian in 1316. Within the city, the first half of the 14th century was marked by civil war-like unrest, which was connected with disputes between the guilds and the urban patriciate, which had largely arisen from former imperial bailiffs and carried out the rule. In 1345, an interim solution was found in the form of the "Kleiner Schwörbrief", which temporarily pacified the situation by granting the guilds a decisive say in political and legal matters for the first time.

Under Ulm's leadership, the Swabian League of Cities was founded in 1376 as an alliance of 14 Swabian imperial cities. Ulm was chosen as the "suburb" (i.e. main place for meetings of the alliance) and was given the title "Haupt- und Zierde Schwabens" (main and ornamental city of Swabia). On June 30, 1377, the construction of Ulm Cathedral began, since the old church was located outside the city walls and the inhabitants could not go to church during a siege by Emperor Charles IV that had taken place shortly before. After the defeat in the First City War in 1388, the Swabian League of Cities fell apart. As a result, Ulm lost influence on the other Swabian towns, but remained so influential both economically and politically that it maintained numerous, largely independent branches in almost all the important trading centres of Europe (e.g. Venice, Vienna, Antwerp/Amsterdam, Constantinople/Istanbul). In 1396, Geislingen with Helfenstein Castle, Altenstadt, Amstetten, Aufhausen and other places came to the town when the Count of Helfenstein had to settle his debts to the town.

The Großer Schwörbrief, the Ulm constitution, came into force in 1397 after the compromise of the Kleiner Schwörbrief "became increasingly unsatisfactory". It regulated the distribution of power and the duties of the mayor. The guilds now had 30 council seats, the patricians only 10. At the same time, the patricians were denied the right to vote. The mayor had to give account to the inhabitants. Schwörmontag (penultimate Monday in July) has been a holiday in Ulm ever since.

In 1480, a new city wall was built in the middle of the "raging river". It extended from the Herdbruckertor, built in 1348, to the Fischertor, located at today's Wilhelmshöhe. This city wall along the Danube, which still exists today, replaced the old wall, which only remained in parts, which met the ashlar humpback wall of the Staufer palace from the Fischerturm via the Schweinemarkt and the two Blauarme (remains preserved in today's Häuslesbrücke) at an almost right angle and then followed this in an easterly direction. The medieval wall was then rebuilt in 1527 by the Nuremberg master builder Hans Beham the Elder according to Albrecht Dürer's fortification theory (published in Nuremberg in the same year under the title Etliche underricht/zu befestigung der Stett/Schlosz/und flecken).

Dürer's ideas were implemented by Beham as follows: The wall-wall trench defense, which took the place of the wall, was to better withstand the fire of the then modern firearms and additionally enable the defender to better position his own artillery. For the artillery, ramps were also built from the city side. On the outside, a breastwork defence with large embrasures was built. Dürer's fortification ideas were further implemented by radically demolishing the towers of the city gates, which were particularly vulnerable to artillery fire due to their height, and providing them with low octagonal projectiles. In addition, Dürer's system provided for round bastions to be placed in front of the ramparts, from where the moat could be flanked by artillery fire. The city fortifications at Glöcklertor, Neues Tor and Frauentor were also modernised accordingly. The Italian-style bastion fortifications built by Gideon Bacher at the beginning of the 17th century, which shifted the lines of defence far out into the apron, changed the cityscape even more decisively than Beham's alterations. Immediately afterwards (from 1617 to 1622), the Dutch engineer Johan van Valckenburgh and various successors set new standards with their conversions and new constructions according to the Dutch system, which at that time was considered the ultimate in fortification architecture. What remains of their work is essentially the Wilhelmshöhe/Promenade area. These new works cost around two million gulden, which had to be raised through taxes.

Between 1484 and 1500, the widely travelled Dominican Felix Fabri, who worked in Ulm, published his Tractatus de civitate Ulmensi (Treatise on the City of Ulm). It is considered to be the oldest surviving chronicle of the city of Ulm. In it, Fabri not only describes the present of the city in his time, but also attempts to portray its history as comprehensively as possible. The autograph of this work, written in Latin, is kept in the Ulm city archives.

Imperial city in the early modern period (1500 to 1802)

The city's development reached its economic and cultural peak around 1500: after Nuremberg, Ulm possessed the second largest imperial city territory in the area of today's Federal Republic of Germany. Three towns (Geislingen, Albeck and Leipheim) and 55 villages belonged to the territory. The city was an important trading centre for iron, textile goods, salt, wood and wine. At the same time, Ulm developed into one of the most important art centres in southern Germany from the middle of the 15th century. Works of art produced in Ulm (especially elaborately designed sculptures and winged altars) became "export hits" far beyond the city limits and were traded as far as Vienna, Sterzing (South Tyrol) and the Netherlands. The rhyme that underpinned the city's position in the world at that time also dates from this period:

Venetian power,

Augsburg splendor,

Nuremberg wit, Strasbourg cannon,

and Ulm money rule

the world.

Ulm money in verse refers not only to the coinage minted in Ulm and used abundantly by Ulm merchants and bankers, but also to what constituted Ulm's actual wealth - barchent, a mixed fabric made of cotton and linen. The barchent, which was given the Ulm seal after the strictest inspection, vouched for such an exceptionally high quality that, being in demand throughout Europe, it was as good as money.

Due to its economic and political importance, Ulm also became the capital, i.e. the meeting place and administrative seat, of the Swabian League. This alliance, founded in 1488, served to unite the Swabian imperial estates, ensured a lasting peace and was an essential element of imperial reform. Although the Swabian League broke up again in 1534 as a result of the Reformation, Ulm's importance in this alliance made it not only an important political centre, but also the de facto administrative centre in Swabia.

With the founding of the Swabian Imperial Circle as one of a total of 10 Imperial Circles, with which Emperor Maximilian I reorganized the administration of the Holy Roman Empire in 1500 and 1512 respectively, Ulm was once again able to build on its supremacy among the Swabian cities and imperial estates. The city became the main meeting place of the newly formed Swabian Imperial Circle. The imperial district congresses (i.e. the decision-making assemblies of the imperial estates united in the Swabian imperial district) took place in the Gothic town hall until the end of the imperial city period. Between 1583 and 1593, Hans Fischer and Matthäus Gaiser built the New Building in the style of the late Ulm Renaissance as an alternative accommodation for the city administration during the Imperial Circle Days. As a multi-purpose building, it served simultaneously as a council and jury house, courtroom, prison and municipal warehouse for salt, wine and grain.

From 1694 onwards, the Swabian Imperial Circle maintained a permanent standing army, the administration and material stocks of which were largely housed in the Ulm armoury.

The discovery of America (1492) as well as the sea route to India (1497), but also the strong local competition in the barchent business by the Fuggers, who at the beginning of the 16th century increasingly "redirected" the lucrative barchent trade to their newly acquired possessions in the lower Illertal, caused Ulm's prosperity and influence to fade quickly soon after 1500. The emergence of new trade centres and the shift of the most important trade routes towards the Atlantic led to a gradual economic decline of the city. Last but not least, religious tensions also contributed to this. In 1529, the city was one of the representatives of the Protestant estates (Protestation) at the Diet of Speyer. Its citizens demanded the unhindered spread of the Protestant faith. In 1531, the city joined the Protestant faith by vote of the citizenry. The subsequent iconoclasm, in the wake of which over 30 churches and chapels were demolished or profaned and well over 100 altars (over 60 in the cathedral alone) were destroyed or removed, also meant the abrupt end of Ulm as a centre of art. Conflicts with the emperor and other imperial estates led to Ulm losing 35 of its villages through looting or pillaging until 1546 (Schmalkaldic War) and finally having to submit to the Catholic Emperor Charles V, who in 1546 abolished the city's constitution of 1397, which had been in force until then (the "Großer Schwörbrief"), and granted the city's nobility (patricians) sole decision-making power in the city through the so-called "Hasenrat".

In the course of the next centuries, the former wealth of the town was reduced by further wars, especially during the Thirty Years' War and the War of the Spanish Succession, by devastating epidemics, reparation payments and extortions of various besiegers and occupiers to such an extent that the town was bankrupt around 1770 and had to sell further land (Herrschaft Wain). In 1786 the Ulm area still comprised the following administrations: Obervogteiamt Geislingen, Oberämter Langenau, Albeck and Leipheim as well as the offices of Süßen, Stötten, Böhringen, Nellingen, Weidenstetten, Lonsee, Stubersheim, Bermaringen and Pfuhl.

Ulm near Bavaria (1802 to 1810)

The reorganization of Europe by Napoleon also affected Ulm. In 1802, even before the proclamation of the Imperial Deputation of 1803, the city lost its independence and was incorporated into the Electorate of Bavaria. Following Ulm's leading role within the dissolved Swabian Imperial District, Ulm became the seat of the provincial administration of the "Bavarian Province of Swabia" (predecessor of today's Government of Swabia). On October 14, 1805, a decisive battle of the Napoleonic Wars took place near the city (Battle of Elchingen), which led to the Battle of Ulm on October 16-19, from which Napoleon emerged victorious. After the French Marshal Ney had crushed the Austrians (for which he was made Duke of Elchingen), the Austrians retreated to Ulm, where they were besieged and surrendered shortly afterwards. This cleared the way east for Napoleon to fight the decisive battle against the Russians and Austrians at Austerlitz. In 1810, Ulm passed from the Kingdom of Bavaria to the Kingdom of Württemberg through an exchange of territory between Bavaria and Württemberg, which was regulated in the corresponding border treaty.

Border and provincial town in the Kingdom of Württemberg (1806 to 1918)

For Ulm, the transfer to Württemberg had serious consequences that continue to this day. Although by far the greater part of the former territory of the imperial city north of the Danube came with Ulm to Württemberg, it was to a large extent no longer subject to direct administration by Ulm, but was assigned to other offices and head offices (especially Geislingen, which had previously belonged to Ulm itself). The smaller, but for Ulm economically more important southern part of the former Ulm territory remained Bavarian, became "foreign" and formed the basis of the future city of Neu-Ulm. Ulm had thus become a border town.

What the loss of its hinterland south of the Danube meant for Ulm can be illustrated by the fact that important Ulm supply and disposal facilities were located south of the Danube. From the central Herdbrücke upstream to the mouth of the river Ill the Iller rafts landed, mostly heading for Ulm as their final destination, but sometimes also travelling as far as Vienna. They were mostly pure tree rafts, but there were also so-called Bäderische, which consisted of already pre-cut boards. The raftsmen brought not only timber for the town, but also firewood, salt and delicacies such as cheese (from Switzerland and the Allgäu), snails, wine (from the growing areas around Lake Constance or from Italy) or cherry brandy. Between today's railway bridge and the Gänstor bridge, on the southern bank of the Danube, there was a carpenter's yard for construction timber, a timber trading yard and another timber yard for storing and selling construction timber and firewood, which was of supra-regional importance.

Furthermore, there were several shipyards south of the Danube in the immediate vicinity of the Herdbrücke at the so-called "Schiffbauerplatz", where the so-called "Ulmer Schachteln" (Ulm boxes) were built for the Danube shipping that started here. After their completion they were loaded with goods at the so-called "Schwal" and launched into the water. A little further downstream, the gardeners' guild maintained a fertilizer yard, which was especially important for the impressive number of tree, fruit and pleasure gardens also located to the south. Facing the Steinhäule were the facilities for the disposal of animal carcasses, which were under the administration of the city's executioner. At the same time, the latter was the master of the wash (knacker, butcher, clover master).

The imperial town's shooting house was also located south of the Danube. There the shooting society used to hold shooting practice several times a week. At the same time, the southern bank of the Danube was also the preferred recreational area for the people of Ulm, where they went for walks, promenaded and stopped off at the taverns. When the Danube became a border river as a result of the Napoleonic wars and territorial shifts between the new kingdoms of Württemberg and Bavaria, there was suddenly a passport obligation for walkers, this also for those Ulm citizens who had their workplace on the other side of the Danube.

With the annexation to Württemberg, Ulm became the seat of an initially very small Oberamt, the Oberamt Ulm. One year later, the city received the designation "Our good city" and thus the right to its own member of the state parliament.

In 1811, Albrecht Ludwig Berblinger, "the tailor of Ulm", was to demonstrate the flying machine he had designed on the occasion of the inaugural visit of the King of Württemberg to the city. According to eyewitnesses, Berblinger successfully completed several gliding flights of several dozen meters "over meadows and gardens" in the area of the upper Michelsberg. Inconveniently, Berblinger was not to present his flying skills there, but on the high bank of the Adlerbastei near the Herdbrücke. Berblinger shied away from the demonstration because he correctly judged the prevailing thermals there to be extremely unfavourable for flight experiments. The following day, the king was no longer present, but his son was, and the Ulm flying pioneer was back at the starting line. According to an ondit, Berblinger, who was still hesitating, was pushed off the Adlerbastei and landed in the Danube instead of on the Bavarian bank. Modern flying competitions have shown that the place chosen for Berblinger's flight demonstration offers very problematic conditions for gliding over with non-motorized flying machines. For Albrecht Berblinger the failed flight demonstration had devastating consequences. Far beyond Ulm he became a ridiculous figure of fun and was defencelessly exposed to the ridicule of his contemporaries. He himself gave up his experiments in bitterness, withdrew and died unrecognized and completely impoverished. In the meantime, Berbinger's honour has been restored (not only in Ulm) with regard to his estimation as a pioneer of flight. In addition to contemporary reports, modern replicas of and experiments with Berblinger's flying machine have clearly proven that it was indeed airworthy and that considerable distances can be covered with it in good thermals.

In 1819, Ulm became the seat of the Württemberg Danube district (roughly comparable to a governmental district) and was able to significantly expand the area of jurisdiction of the Ulm chief bureau by incorporating the short-lived Albeck chief bureau.

The opening of the first continuous line of the Württemberg railway network from Heilbronn to Friedrichshafen on June 1, 1850, as well as the enormous building tasks of the construction of the Federal Fortress and the completion of the Ulm Minster, which had been started in the middle of the 19th century, brought new life to Ulm, which had meanwhile become a "provincial town with 12,000 inhabitants". In the wake of the construction of the federal fortress with 53 fortifications around Ulm and Neu-Ulm as well as the completion of the cathedral, as a result of which Ulm received the highest church tower in the world since 1885 (the inauguration of the new west tower was on May 31, 1890), prosperity moved in again.

The result of this revival was a sharp rise in the number of inhabitants and the founding of numerous commercial and industrial enterprises. For example, the Ulm pharmacist Gustav Ernst Leube rediscovered the art of cement production, which had been forgotten since late antiquity, and founded Germany's first cement factory in 1838 with his brothers, Wilhelm and Julius Leube. Conrad Dietrich Magirus, commander of the volunteer fire brigade in Ulm, was engaged in the construction of fire-fighting equipment. He is considered the inventor of the mobile fire escape. In 1864, Magirus became a limited partner in the newly founded Gebr. Eberhardt offene Handels- und Kommanditgesellschaft, which manufactured and sold fire fighting equipment. After disagreements between Magirus and the Eberhardt brothers, Magirus then founded his own company in 1866, which he named Feuerwehr-Requisiten-Fabrik C. D. Magirus. In 1893 Karl Heinrich Kässbohrer, scion of an old Ulm fishing and shipping dynasty, founded the Kässbohrer coach factory. From 1910 onwards, bodies for passenger car chassis were mass-produced there for the first time. The company also received the first patent for a combined bus body for passenger and freight transport. In 1922 Kässbohrer developed the first truck trailer. Against the background of the important supra-regional function of the Ulm commander Magirus, the 1st German Fire Brigade Day was held in Ulm in 1854.

The troops of the federal fortress stationed there since the middle of the 19th century also played an important role in the development of Ulm and Neu-Ulm. In 1913, Ulm had 60,000 inhabitants, including more than 10,000 soldiers. Even in 1938, shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, the twin city of Ulm/Neu-Ulm was the largest garrison in the German Reich, with more than 20,000 soldiers. The tolerant-rich Ulm citizens were not particularly fond of warlike actions and the military per se. War had seldom brought good to the city in its history. The Ulmers' aversion to anything too military was shown, for example, by the fact that the imperial city very early on left large parts of the city's defense to mercenaries from outside, for whom the so-called "Grabenhäuschen" were built along the city wall. Ulm also always tried to settle territorial disputes with its neighbours diplomatically, if necessary by paying horrendous sums of money. Large parts of the former territory of the imperial city had come into the hands of the people of Ulm by purchase or debt redemption, not by military means. The introduction of compulsory military service after the involuntary annexation to Bavaria and Württemberg also met with bitter and long-lasting resistance in Ulm. All in all, Ulm was repeatedly the object of various desires in the course of its history, which were mostly pursued by warlike means to the detriment of the city. Thus, as the capital of the Swabian League of Cities or the Swabian Imperial Circle, the city was always influenced by its own or foreign military.

See also: Military in Ulm

Ulm during the Volksstaat and the NS dictatorship (1918 to 1945)

In 1918/19, through the Volksstaat Württemberg, the democracy of the Weimar Republic also became effective in Ulm. In 1919, the Württemberg Municipal Law introduced the active and passive democratic right to vote for all people. A representative democracy with city councils was created. Parties were founded, which organized themselves into factions in the city council and controlled the administration with the democratically elected mayor. However, the parties that wanted to abolish this democracy, above all the National Socialists, became stronger and stronger. The First World War and the following Great Depression had hit Ulm particularly hard, as the city's commercial enterprises were designed to be heavily export-oriented and, as former armaments enterprises, were directly affected by reparations demands and manufacturing restrictions under the Treaty of Versailles. The radical reduction in the number of military personnel stationed in Ulm due to the defeat in World War I also had an extremely negative effect on the local economy. This was compounded by the destruction of the currency by inflation in 1922/1923, which briefly led to a regional currency of its own, the Markengeld Wära.

The National Socialists and the parties allied with them that rejected democracy succeeded in blaming those parties that supported the Weimar Republic for the reparations obligations, the poor economic situation and also for the dismantling of the military, combined with a high proportion of anti-Semitism: the Jews were seen as the originators of all the negative events of the Weimar Republic. In addition, there was the fight against the communists, who rejected the Weimar Republic itself. Thus, from the late 1920s onwards, there were high proportions of votes for the National Socialists in Ulm.

In the Ulm Reichswehr trial in October 1930, three officers of the Ulm-based Artillery Regiment 5 were charged with preparation for high treason and finally sentenced to 18 months in prison each for distributing political (NSDAP) propaganda. Adolf Hitler himself was questioned as a witness, used this to make a propaganda appearance, but also assured during his questioning by the judge that he would only seek political change through constitutional means.

Immediately after the National Socialists seized power on January 30, 1933, the persecution of Weimar democrats, communists and also Jews began. This was initially carried out by the SA and SS on behalf of the NSDAP, later by the police authorities. Many of the victims of this persecution were incarcerated and mistreated without trial from 1933 to 1935 in the Oberer Kuhberg concentration camp, one of the fortifications of the federal fortress of Ulm. Later, the remaining prisoners were transferred to the Dachau concentration camp. Among them was Kurt Schumacher. At the same time, democratic bodies and the democratic rule of law were abolished. The true rulers of Ulm from 1933 onwards were the NSDAP district leader Eugen Maier and his superiors in the NSDAP Gau Württemberg-Hohenzollern.

In 1933, the Wuerttemberg Political Police established a field headquarters in the Neues Bau, which functioned as an office of the Secret State Police from 1936 until the end of the war.

From 1933 to 1935 the concentration camp Oberer Kuhberg existed with mainly political prisoners in the fort of the same name of the federal fortress Ulm.

On April 22, 1934, oppositional representatives of the Protestant Church from all over Germany (German Reich) issued the Ulm Declaration in Ulm Cathedral, in which they opposed efforts to subordinate the independence of the Protestant Church to the National Socialist state.

Due to the administrative reforms during the Nazi period in Württemberg, the city of Ulm became a district-free city in 1938 and also became the seat of the district of Ulm, which had emerged from the old Oberamt.

In the so-called Reichspogromnacht (November 9/10, 1938), the Ulm synagogue Am Weinhof 2, which had been consecrated in 1873, was set on fire by an Ulm SA group. In addition, members of the Jewish community were mistreated, in which other Ulm citizens also participated. 56 men were imprisoned for several months in the Dachau concentration camp. Two of those arrested from Ulm did not survive the ordeals there. The city fire department quickly extinguished the synagogue fire, but not to prevent the Jewish community's sanctuary from burning, but because they wanted to prevent the fire from spreading to neighboring buildings. To complete the Nazi pogrom, the city government ordered the demolition of the building a few days later, forcing the Jewish community to finance it themselves. After the "Reichskristallnacht" the remaining people of Jewish faith living in Ulm were forcibly quartered in so-called Jewish houses. From 1941 to 1942, the remaining Ulm Jews were deported to the extermination camps in the East, where they were murdered. Only a few of the deported Ulm Jews survived. From 1990 until the new synagogue was built on the Weinhof opposite in 2012, a memorial plaque at the staircase of the Sparkasse Neue Straße 66 commemorated the 122 Ulm Jews who were persecuted and murdered in the Shoa and their place of worship. The memorial book of the Federal Archives for the victims of the National Socialist persecution of Jews in Germany (1933-1945) lists 195 Jewish inhabitants of Ulm by name, who were deported and mostly murdered.

There was also isolated resistance against the National Socialist state. In 1942, a group of high school graduates around Hans and Susanne Hirzel as well as Franz J. Müller formed the Ulm branch of the well-known Munich resistance group White Rose, in which Hans and Sophie Scholl from Ulm were active. Both resistance groups were captured in 1943. Some of their members were sentenced to death, others to prison.

In 1944, the heavy air raids on Ulm began. At the end of the war - especially as a result of the major attack of 17 December 1944 - 81% of the historic old town was destroyed, but the cathedral was largely spared.

In 1945, the Dachau concentration camp maintained the SS work camp Ulm in the district of Söflingen with 30 to 40 prisoners for the construction of submarine parts at Klöckner-Humboldt-Deutz.

On April 24, 1945, Ulm was occupied by US troops. Elsewhere in Germany, the war continued until early May. The war ultimately ended on May 8 with the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht.

Ulm in the post-war period (1945 to 2000)

Ulm was part of the American occupation zone and thus belonged since 1945 to the newly founded state of Württemberg-Baden, which was merged in 1952 into the current state of Baden-Württemberg.

Ulm's inner city, which had been largely destroyed, was rebuilt in the decades following the end of the war. The question of whether the reconstruction should be historic or modern led to heated debates. Most of the city was rebuilt in the style of the fifties and sixties. In order to realise large traffic projects such as the "Neue Straße" as an east-west main road, even still preserved historical buildings were sacrificed. However, there were also reconstructions of individual buildings that were significant for the city's history, and numerous modern buildings were more or less oriented towards historical forms, e.g. the pointed gables typical of Ulm. (See also Culture and Sights - Buildings - Cityscape)

However, the reconstruction was not limited to the old city centre of Ulm. The newly designated industrial area in the Danube valley (1951) was of great importance for the further economic development of the city. The new Eselsberg district was able to accommodate numerous displaced persons, which quickly swelled the population back to pre-war levels and beyond.

After Ulm had already hosted the 1st German Fire Brigade Day in 1854, the 22nd German Fire Brigade Day was also held there from 29 to 31 May 1953. It was the first after the Nazi regime and the Second World War.

The history of the Hochschule für Gestaltung (College of Design), which set the style for the fifties and sixties but has since been closed again, began in 1953. An engineering school opened in 1960 and was merged into the University of Applied Sciences for Business and Technology in 1972. An important impulse for the city was the foundation of the University of Ulm (1967), to which the University Hospital, formed from previously municipal clinics, was affiliated in 1982.

On 1 January 1973, the district reform in Baden-Württemberg came into force. Ulm became the seat of the newly formed Alb-Donau-Kreis (Alb-Donau district), but remained a district-free city itself. In 1980 Ulm exceeded the 100,000 population mark for the first time and thus became a large city. In the same year, Ulm hosted the first State Garden Show in Baden-Württemberg, in which the neighbouring Bavarian city of Neu-Ulm also participated.

The overcoming of the economic crisis at the beginning of the 1980s also turned the former industrial city into a service and science centre, which in 1987, with a population of 104,000, could boast the remarkable figure of 84,000 jobs.

Ulm in the 21st century (since 2001)

In 2004, the city celebrated several significant events: first, the 1150th anniversary of the first documented mention of Ulm, and second, the 125th birthday of Albert Einstein, who was born on March 14, 1879, in what is now Bahnhofstrasse. (However, the family moved to Munich shortly after Albert's birth in 1880. A sculpture now stands on the site of his birthplace in honor of the city's prominent Jewish son, who was expatriated by the Nazi rulers). Another major event was the 95th German Catholics' Day from 16 to 20 June 2004 under the motto "Life from God's Power", attended by about 30,000 believers.

In 2015 Ulm was awarded the honorary title "Reformation City of Europe" by the Community of Protestant Churches in Europe.

Incorporations

Formerly independent municipalities or parishes that were incorporated into the city of Ulm. The additional area indicates the area added to the total area of the city in the year of incorporation.

| Date or year | Locations | Increase in ha | Source |

| 1828 | Böfingen, Örlingen and Obertalfingen | ? | |

| November 6, 1905 | Söflingen | 1448 | |

| April 1, 1926 | Grimmelfingen | 471 | |

| April 1, 1927 | Wiblingen | 809 | |

| September 1, 1971 | Jungingen | 1354 | |

| January 1, 1972 | Unterweiler | 452 | |

| February 1, 1972 | Moravia | 891 | |

| May 1, 1974 | Eggingen | 810 | |

| July 1, 1974 | Donaustetten | 598 | |

| July 1, 1974 | Sing in | 651 | |

| July 1, 1974 | Ermingen | 837 | |

| July 1, 1974 | Gögglingen | 514 | |

| 1 January 1975 | Teaching | 614 |

Population development

→ Main article: Population development of Ulm

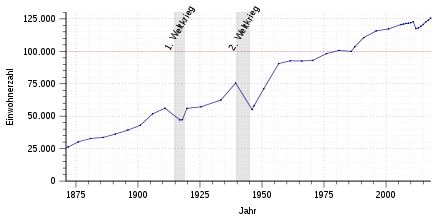

Between 1890 (36,000 inhabitants) and 1939 (75,000 inhabitants), the city's population doubled. Due to the effects of the Second World War, Ulm lost about 30 percent (20,000) of its inhabitants by 1945. By 1951, the population had returned to its pre-war level. In 1980, the city's population exceeded 100,000 for the first time, making it a major city. This status was lost intermittently in the 1980s, but since the 1987 census the population has been consistently listed above 100,000. According to the 2011 census, the number as of 9 May 2011 was 116,761 inhabitants, which was lower than previously thought (according to the State Statistical Office, Ulm had over 120,000 inhabitants at the end of 2010). At the end of December 2019, according to the update of the Statistical Office of the State of Baden-Württemberg, there were 126,790 people living in Ulm with their main residence, and the number of inhabitants thus reached a new historic high for the fourth year in a row. As of 31st December 2004, 19,570 inhabitants (16.3 percent) had a foreign passport (over 100 nations). 14.4 percent of the inhabitants were under 15 years old, 17.5 percent 65 years old or older. Thus Ulm, similar to other German cities, has a relatively low birth rate, but the number of inhabitants is still increasing by 0.5 percent annually due to immigration.

According to a report of the Statistical Office of Baden-Württemberg, the city or the urban district of Ulm will be the youngest district in Baden-Württemberg in 2025. Thus, the average age of the city will increase from currently 41.3 years to 44.5 years, which, however, is still significantly below the average age of other urban and rural districts in the state.

The metropolitan region of Ulm, together with the neighbouring districts of Alb-Donau-Kreis and Landkreis Neu-Ulm, has a population of approx. 500,000.

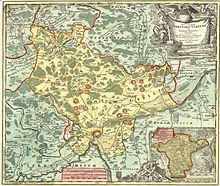

Territory of the Free Imperial City of Ulm (with exclave Wain) according to a map by Johann Baptist Homann from 1725

2005: View from the middle platform of Ulm Cathedral towards the west. On the left the historic Neues Bau, almost all other visible buildings are new.

1955: View from the main tower of Ulm Cathedral to the western Münsterplatz. The gaps between buildings are consequences of the destruction of the old town, especially on 17 December 1944.

New Synagogue

Weinhof before 1927 (with the synagogue destroyed in the pogrom night of 1938)

Fort Oberer Kuhberg (temporary concentration camp)

Ulm in May 1888 with the main tower of the cathedral nearing completion

Wilhelmsburg 1904

Cover with one of the first stamps of the Kingdom of Württemberg, cancellation ULM 1852

First railway station and post office in Ulm in 1855

Ulm (around 1890/1900)

Population development from 1871 to 2017

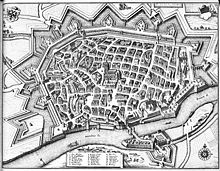

Ulm in three directions around 1650, copper engraving by Merian

View of Ulm around 1490

Secco painting on the south side of the town hall showing Ulm's trade relations

Ulmer Münz and Schiefes Haus (right)

Birds of Ulm, 1597, watercolour by Philipp Renlin

Ulm from above around 1650, copper engraving by Merian

Questions and Answers

Q: Where is Ulm located?

A: Ulm is located in Germany, in the state of Baden-Württemberg.

Q: When was Ulm established?

A: Ulm was started in about 850 AD.

Q: What is across the river Danube from Ulm?

A: Across the river on the right side is Neu-Ulm in Bavaria.

Q: How many inhabitants does Ulm have?

A: Ulm alone has about 120,000 inhabitants, while together with Neu-Ulm they have more than 170,000 inhabitants.

Q: When was the University of Ulm established and how many students does it have?

A: The University of Ulm was started in 1967 and it has about 7000 students.

Q: What is the height of the Ulmer Münster in Ulm and what is noteworthy about it?

A: The Ulmer Münster in Ulm is the world's highest church tower, standing 161.5 metres (530 feet) tall.

Q: Who was born in Ulm?

A: Albert Einstein was born in Ulm.

Search within the encyclopedia