Turtle

![]()

Turtle is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see Turtle (disambiguation).

The turtles (Testudinata, or Testudines if the crown group is meant; formerly also Chelonia from Old Greek χελώνιον "turtle") are an order of Sauropsida and first appeared more than 220 million years ago in the Carnian (Upper Triassic). In classical systematics, they are included in the creepy-crawlies and reptiles, respectively; these designations represent a taxon that is paraphyletic in its traditional range, and are therefore now only informal collective terms.

One distinguishes currently 341 species with over 200 subspecies. The turtles have adapted to the most diverse biotopes and ecological niches. The range extends from Mediterranean land turtle species, gopher tortoises or desert tortoises and the particularly numerous, smaller water turtle species in North America and Southeast Asia to large river turtles in South America, giant turtles on some island groups, soft-shelled turtles in Asia and snake-necked turtles in Australia to the largest, the leatherback turtles, which form their own family alongside the sea turtles.

Turtles are cold-blooded, egg-laying reptiles. Fossil historically, they are most closely related to some basal diapsids such as Odontochelys semitestacea and Sinosaurosphargis yunguiensis.

The adaptability of the turtles has been able to ensure their continued existence up to the present day. Due to human influences, however, many species are now acutely endangered.

Distribution

With the exception of the polar regions, turtles inhabit all continents. They are found in different land areas, in tropical forests and swamps, in deserts and semi-deserts, lakes, ponds, rivers, in brackish water areas and in seas, in temperate, tropical and subtropical climates.

In Europe, there are only nine autochthonous species besides sea turtles, four terrestrial and five aquatic species. Germany, Austria and Switzerland are home to only one native turtle species, the nominate European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis orbicularis).

Distribution: land, water and pond turtles (black), sea turtles (blue)

Physique and way of life

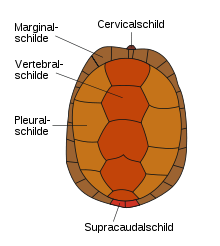

Structure of the tank (Pantex)

For turtles, the carapace, which already accounts for about 30% of the weight, is undoubtedly the anatomically decisive characteristic. No other vertebrate shows a comparable anatomy. Similar to the exoskeleton of insects, the shell of turtles, which consists of the dorsal carapace (carapace) and ventral carapace (plastron), encloses all important body regions and organs except the head.

The bone armor consists of massive bone plates that form a ribcage, which has evolved from the vertebral arches and ribs of the endoskeleton of vertebrates. In contrast to all other vertebrates with a shoulder girdle, the shoulder bone (lat. scapula) has been pushed under the ribs. This largely rigid bony armor requires an adjustment of respiration, which must be supported by movement of the extremities with the help of powerful muscle packages.

Depending on the species, the bony shell is covered by a leathery skin layer (e.g. soft-shelled turtles) or the typical layer of horny shields (scuta), which in turn consist of keratin. The coloration of the scutes depends mainly on the origin of the turtle, because most species are adapted to their habitat in terms of color.

In ornamental, lettered, ornamental and humpback turtles, the horny shields renew themselves regularly, as the older outer horny shields detach and the newly formed horny shields appear underneath. In other turtles, growth rings develop and the outer horny shields only wear down a little due to abrasion from the outside.

These horny shields can be divided into the following groups, with species-specific variations in number and presence:

Horny shields of the dorsal carapace (carapace)

(from cranial to caudal or from front to back)

- 1 neck shield (cervical or nuchal)

- 24 Marginalia (Marginalia)

- the last two marginal shields are the postcentralia and together form the supracaudal or caudal shield (Supracaudale, Syn.: Caudale), in some species this is also undivided

- 5 Vertebral shields (Vertebralia)

- 8 rib shields (pleuralia or costalia)

Horn shields of the abdominal carapace (plastron)

(from cranial to caudal or from front to back)

- 2 Throat shields (Gularia)

- 2 Arm Shields (Humeralia)

- 2 axillary shields (axillaria)

- 2 chest shields (pectoralia)

- 2 abdominal shields (abdominalia)

- 2 hip shields (Inguinalia)

- 2 leg shields (femoralia)

- 2 anus shields (Analia)

The suture and interlocking points of horn and bone carapace do not lie on top of each other, but are shifted against each other. This further increases the strength of the carapace. The appearance of the entire carapace differs greatly depending on the species. For example, the dorsal carapace of many species has one or three longitudinal keels, especially when young. In the case of the humped turtles and the Chinese three-keeled turtles, these strongly pronounced humps and keels even give them their names. Several genera (for example, the box turtles and the hinged turtles) can fold up their abdominal carapace with the help of a hinge, thus closing the entire shell. Hinged turtles have two hinges, allowing them to close the front and back openings independently. The hinge in the carapace of articulated turtles provides a similar function.

The development of the turtle shell is partly interpreted as an adaptation to the water habitat. According to this, the rigid body enabled faster progress under water, especially in contrast to the sinuous movements of other reptiles. However, even the oldest known turtle fossils show a highly developed shell, so that its origins and development can only be speculated.

Sensory services

Turtles see very well. They can differentiate colors better than humans, because their eyes, like all reptiles, have four different color receptors. They are thus able to perceive parts of the near infrared and ultraviolet radiation. Grey tones, on the other hand, they seem to differentiate less.

The lens of aquatic turtles is designed to compensate for the angle of refraction of water. This allows the animals to clearly see enemies and food even in water. Hunting turtle species can see both spatially and in panorama by changing their eye position. The speed of visually perceived movements affects the flight response. If you approach a turtle very slowly, it will flee later than if you approach it quickly.

The sense of smell is particularly strong in turtles. Aquatic turtles smell by chewing-pumping movements of the lower jaw and throat. The olfactory receptors are located in the pharynx. Through smell, they detect suitable food or soil in which to bury their eggs. In addition, sexual partners are recognized by smell (in aquatic species also under water), probably even over greater distances.

Turtles have a fully developed inner and middle ear, but no outer ear. They therefore do not hear sounds to the same extent as humans. They perceive sound waves of about 100 Hz to 1000 Hz, i.e. mainly deep vibrations (impact sound) from their environment, possibly also feeding noises from conspecifics. According to a study from Italy, female turtles of the genus Testudo even react to acoustic signals from males during mating play, whereby they seem to prefer sounds that follow each other quickly and high-pitched tones (small males).

Turtles can compete with all other reptiles in their cognitive abilities. For example, they remember food sources and escape routes. Their sense of direction is also excellently developed and seems to increase with age.

Other well-developed sensory abilities include pain sensation, temperature sense, and balance sense.

vocalizations and communication

Turtles are mostly mute. However, startle reactions are exceptions. Here, these animals expel air by quickly pulling back their head, which produces a hissing hissing sound. In aquatic turtles, hissing threatening sounds are occasionally heard. Males of many tortoise species make beeping or wheezing sounds when mating, much like females do when occasionally fighting with other females for the best egg-laying sites. Tortoises may hiccup briefly after hastily eating fruit or small snails, making a similar sound.

Recent research by a team led by Camila Ferrera of the Brazilian Wildlife Conservation Society and Richard Vogt of the Amazon Research Institute in Manaus has found that low-pitched sounds are used for acoustic communication between individuals. Mother animals communicate with newly hatched ones. Embryos communicate acoustically with each other - before hatching - to possibly synchronize hatching.

Locomotion

Turtles move both on land and in water with sinuous movements typical of reptiles, with the shell being carried in the air on land. This type of locomotion reduces the energy required for movement in the water, but sometimes appears awkward on land. Only sea turtles have evolved a method of locomotion unique to reptiles. They flap their front limbs, which have formed into flippers, up and down. In this way, they achieve high speeds under water with optimised energy requirements, which enables them to cover even longer distances. The limbs of land turtles or fresh and brackish water turtles are also adapted to the respective habitat. In most cases, the connection to the water can be determined by the presence and development of webbed feet, especially on the rear extremities. The legs of turtles that inhabit hot steppe areas, on the other hand, are columnar and protected all around against injury and dehydration by strong horny scales.

Food intake and nutrition

In 220 million and 160 million year old fossil turtles, respectively, teeth were discovered, which, however, have regressed in the course of evolution. Today's turtles do not have teeth, but rather jaw ridges made of horn substance that have been transformed into powerful cutting tools, which in their entirety form the beak. Like all reptiles, turtles do not chew their food, but either swallow it whole or tear off pieces with their mouths, using their front limbs to help them.

Turtles are mostly omnivores. Depending on the species, however, the vegetable (herbivore) or the meat (carnivore) diet usually predominates. Some species, especially those living in water, switch from a protein-rich diet of aquatic insects as juveniles to a lower-energy, but easily obtained plant-based diet when they are mature. Turtles need a calcium-rich diet for their comparatively large bony skeleton and, in some cases, for the formation of hard-shelled eggs. Usually the diet is very varied, as the animals are not very choosy in their search for food. Depending on the species, their diet ranges from meadow herbs, flowers, fruits, aquatic plants and algae to insects, worms, snails, fish, starfish, crabs and jellyfish to carrion and excreta from mammals.

Some species, however, are distinct food specialists, such as the leatherback turtle, which specializes in jellyfish, or the Malaysian pond turtle, whose English name, Snail Eating Turtle, and powerful jaws reveal a preference for cracking shell snails. Some other turtle species have also adapted their physique to special hunting methods, such as the vulture turtle, which waits quietly with its mouth open until a fish is interested in the worm-shaped tip in its mouth. Another unusual method of capture is practiced by the fringed turtle (mata-mata), which lurks camouflaged in the mud with an algae-covered shell and sucks in its prey by suddenly ripping open its huge maw.

Sex differences and reproduction

In a direct comparison between sexually mature males and females, one notices that the excretory opening in the root of the tail of the female, the cloaca, is located closer to the edge of the carapace, whereas that of the male is located more towards the end of the tail. The tail is also usually much longer in the male and wider at the base, as it houses the penis, which is only extended for mating. Other common sex differences include smaller body size and a more inwardly curved abdominal carapace in males, which facilitates copulation. In addition, there are secondary sexual characteristics that are limited to individual genera, species, or even subspecies, such as elongated anterior claws on the male in the ornate turtles or different coloration of the iris in some box turtles and some subspecies of the European pond turtle. The secondary sexual characteristics are not yet visible in the hatchling, but are only developed in the run-up to sexual maturity.

At mating time, the males, which in some species colonize other ecological niches, specifically seek out the females. They are probably guided by olfactory hormones (pheromones). The actual act of mating is preceded by a courtship display in most species, which appears rather crude to humans. Depending on the species, it comes to the pursuit and encirclement of the female with sometimes violent bites into her extremities and ramming against the carapace. During copulation, the males ride up and partially cling to the female's carapace. Due to the ability to store sperm, the female remains capable of fertilizing for several years after a successful copulation without having to copulate again, which may explain the turtles' success in colonizing new habitats, such as the Galapagos Islands.

The mating season for species from the temperate climate zone is predominantly in autumn and spring, whereas tropical species tend to be more dependent on rainy seasons and humidity. Egg-laying (oviposition) occurs a few weeks after fertilization and takes place on land in all species. In accordance with the seasons, the pregnant female searches for a suitable place for oviposition, for which she often accepts long, dangerous hikes. She pays attention to the sunny position of the site, its soil conditions, flood resistance, and probably other factors as well. Once selected, this egg-laying site is usually retained for many years. The female digs a deep, often pear-shaped pit with her hind legs, carefully lays the eggs in it and carefully scrapes the pit closed again so that no nest predators are attracted. Most female turtles leave the incubation of the eggs to the sun. Few turtle species practice a kind of brood care by guarding the nesting site. These include the brown tortoise, a species of the hind Indian tortoise genus. Females of this species use their front legs to scrape together a nesting mound of leaves, sand and grass that is 1 to 2.50 metres in diameter and between 20 and 50 centimetres high. In the middle of the pile, the female digs the nest pit with her head. She then guards the clutch for a period of 2 to 20 days. Sometimes she lies down directly on the nest pit. However, she also defends her nest pit against predators by biting or trying to push the predator away from the nest pit.

Eggs vary greatly in shape, size, and texture among species. In snake-necked turtles, mud turtles, softshell turtles, most land turtles except the genus Manouria, and in many Old World terrapins, e.g., Hinged and American terrapins, they are surrounded by a hard calcareous shell, as in birds. Sea turtles, leatherback turtles, and alligator tortoises, however, encase their eggs only with a leathery skin and a protective layer of mucus; this is also true of most pelomedus turtles. Among New World terrapins, all members of the Deirochelyinae lay soft-shelled eggs; among the Emydinae, members of the genera Actinemys, Emydoidea, and Emys have hard-shelled eggs, and the remaining genera have soft-shelled eggs. Unlike birds, however, the eggs do not have hail strings on which the yolk is rotatably suspended. Therefore, turtle eggs must not be rotated once embryonic development has begun, or the germinal egg will die. The number of eggs and clutches per season varies greatly, from a single egg, e.g. in the smallest tortoise species (Homopus signatus), to 200 eggs in the sea turtles.

In some species, the sex is not genetically determined at fertilization, but is determined by the hatching temperature (e.g. in European aquatic and terrestrial turtle species). In certain temperature ranges predominantly or even exclusively females or males hatch. This circumstance has proven to be an advantage in breeding projects for the protection of the species population. Incubation occurs in about 50 to 250 days, depending on the species. At the end of the development period, the small turtle fills the egg completely. In the case of hard-shelled eggs, she often scores the shell with the egg callus on the upper jaw, opening a first window. In some cases, the shell is also opened with one leg. Then the folded abdominal carapace begins to stretch and completely bursts open the shell. After hatching, the small turtles often remain in the nesting cavity until the yolk sac is completely resorbed, when they dig their way to the surface in a concerted effort. In arid areas, this usually occurs after a late summer rain, which softens the soil and also promises abundant food for herbivores. At the northern limit of their range, turtle hatchlings often overwinter still in the nesting burrow and do not come to the surface until the following spring. The mother does not provide any protection or help in rearing, the young are on their own from hatching onwards and are sometimes even welcome prey for adult conspecifics. Several years pass until sexual maturity. It depends not only on the age, but also on the nutritional status of the animal.

Maximum possible age

Tortoises can reach a very old age. The birth year of the Galápagos giant tortoise (Geochelone nigra) Harriet, who lived at Australia Zoo and died on 23 June 2006, is estimated to be 1830, making her at least 176 years old. American box turtles (Terrapene) are said to be able to live well over 100 years, and sea turtles (Cheloniidae) probably live 75 years or more. If well cared for, ornamental turtles kept as pets will live 40 years or more.

Among the oldest individuals was Timothy, a female Moorish tortoise (Testudo graeca). The former mascot of the British Navy lived to be 160 years old, although she was probably not kept in a species-appropriate manner for the first 40 years of her life on board a warship.

In contrast to the potential maximum age, the average life expectancy of most tortoise species under natural conditions is usually significantly lower. For the Greek tortoise (Testudo hermanni), it is only about 10 years from sexual maturity in nature (Hailey 1990/2000).

Examples of particularly old turtles (according to traditional, usually not entirely certain, data) were:

- Adwaita (b. c. 1750 (?); † 22 March 2006), 256 yrs.

- Tuʻi Malila (b. c. 1773 or 1777; † 19 May 1965), age 188 or 192.

- Harriet (b. c. 1830; † June 23, 2006), age 176.

- Jonathan (* around 1832)

- Timothy (b. c. 1844; † April 4, 2004), age 160.

- King Faruq's tortoise (contradictory information about the date of birth and death)

Size differences

In addition to many species that grow to a size of only 10 to 50 centimetres, such as representatives of the genera Testudo, Emys and Mauremys, there are also the giant tortoises on the Galápagos Islands (Geochelone nigra) and the Seychelles (Dipsochelys dussumieri), which reach a carapace length of over one metre. Sea turtles and the almost extinct Hoan Kiem Lake giant soft-shelled turtle reach much greater carapace lengths. The largest species is the leatherback turtle Dermochelys coriacea with a carapace length of up to 250 cm and a weight of 900 kg.

The smallest turtles are the males of the sawed flat turtle Homopus signatus from South Africa with an average dorsal carapace length of about 7.5 cm and a weight of about 70 g.

Sizes of turtles normally refer to the length of the dorsal carapace without head, legs and tail. Measurements are taken in stick measurements, i.e. straight along the longitudinal axis with the aid of a sliding gauge and not with a tape measure over the carapace arch.

Olive bastard tortoises lay many and relatively small eggs

Generalized arrangement scheme of the horny shields (scuta) on the carapace

Black-knobbed humpback turtle with characteristic expression of the vertebral shields

smooth soft-shelled turtle, no horny shields, only skin covers the bony shell

The carapace (dorsal shield) of a vulture turtle

Head and neck shape of a suction snapper (fringed turtle)

Thousands of olive ridley turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) arrive every year to lay their eggs in the protected area of Playa de Escobilla on the Mexican Pacific coast.

Sea turtle (green turtle) off Hawaii, USA

Hatching process of a Greek tortoise (Testudo hermanni)

An embryo of the olive ridley turtle

Questions and Answers

Q: What are turtles?

A: Turtles are a type of reptile with hard shells on their back.

Q: What are the two types of turtles?

A: The two types of turtles are side-necked turtles and hidden neck turtles.

Q: How many species of turtles are there and where do they live?

A: There are about 356 species of turtles living on land in all continents except Antarctica and in both salt water and fresh water.

Q: What is the order Testudines?

A: The order Testudines includes both living and extinct species, including turtles.

Q: When was the earliest fossil of a turtle found and where was it found?

A: The earliest fossil of a turtle was found in China from the early Upper Triassic age, about 220 million years ago.

Q: Are turtles related to dinosaurs?

A: Yes, turtles are related to dinosaurs.

Q: Why are many turtle species today endangered?

A: Many turtle species today are endangered due to habitat loss, pollution and overhunting.

Search within the encyclopedia