Tunisia

Template:Infobox State/Maintenance/TRANSCRIPTION

Template:Infobox State/Maintenance/NAME-German

Tunisia (Arabic تونس, DMG Tūnis; officially Tunisian Republic, Arabic الجمهورية التونسية, DMG al-ǧumhūriyya at-tūnisiyya) is a country in North Africa. It consists of 24 governorates. Tunisia has just under 12 million inhabitants and is one of the less densely populated states with 71 inhabitants per km².

Tunisia borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east (1,146 km of coastline), Algeria to the west and Libya to the south-east. Its name is derived from the name of its capital Tunis. Tunisia belongs to the Maghreb countries. The largest offshore island is Djerba (514 km²). With an area of 163,610 km², the country is about twice as large as Austria.

The country was subject to the influence of several peoples throughout its history. Originally it was settled by the Berbers. Around 800 BC, the Phoenicians founded the first settlements in the Tunisian coastal strip. The Romans incorporated it into their province of Africa. Christianity subsequently prevailed until Arabisation from the 7th century onwards. The region experienced a cultural heyday in the 12th century. In the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire began its rule, which lasted until the end of the 19th century, when the country became a French protectorate. Tunisia gained its independence in 1956, and from 1956 to 2011 it was ruled continuously in an authoritarian manner by the Neo Destour/RCD unity party. In the wake of the revolution, a Constituent Assembly was elected, which adopted a new constitution in 2014. Tunisia is considered the only democratic country in the Arab world, according to the Democracy Index published by The Economist magazine.

Geography

Tunisia is the northernmost country in Africa and only 140 kilometers from Sicily. It stretches between the Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara Desert, between 37° 20′ and 30° 10′ north latitude and between 7° 30′ and 11° 30′ east longitude. The greatest north-south extent between Ra's al-Abyad (Cap Blanc) and the border station of Bordj el Khadra is about 780 km, and the greatest east-west extent between the island of Djerba and Nefta is about 380 km. The Mediterranean coast has an approximate length of 1,300 kilometres.

The northwest of Tunisia is dominated by the Tell Atlas. Running parallel to the north coast from the Algerian border to the Bay of Bizerte are the mountain ranges of the Kroumirie (700-800 m altitude). This is followed to the northeast by the Mogod mountain range (300-400 m altitude), which slopes down into the Mediterranean Sea, for example at Ra's al-Abyad, in a mostly steep rocky cliff. On the side of the mountains facing away from the wind is the valley basin of the Medjerda, which has water all year round and whose lower reaches belong to the country's most important agricultural zone.

The mountain ridges of the Dorsale run from the northeast (starting at the western edge of Cape Bon) to the southwest with the highest mountain in Tunisia (Djebel Chambi, 1544 m) with a length of 220 kilometers. The north-eastern extension of these mountain ranges is the Cap Bon peninsula with fertile plains and some elevations (Djebel Beno Oulid, 637 m and Djebel Korbous, 419 m), which is, however, considered as an independent landscape region.

East of the Dorsale, along the Mediterranean coast between Hammamet and Skhira, Sousse and Sfax, lies the coastal strip called Sahel (Arabic for coast), which is very fertile due to rain-bringing easterly winds and allows, among other things, large olive tree cultures.

South of the Dorsale is the region of the Central Tunisian Steppe, which forms a transition to the Scot Valley (Chott el Djerid and Chott el Gharsa) at its southern edge with the Northern Mountain Fringe. The landscape, characterized by salt lakes and oases, merges further south at the Eastern Great Erg into the desert landscape of the Sahara with the Jebil National Park. In southeastern direction follows the limestone plateau Dahar with a height of up to 600 m, which connects to the desert steppe of the Djeffara plain with a stratified plain. This landscape extends further across the border into Libya.

Along the Mediterranean Sea, around the Gulf of Gabès lies the littoral zone, characterized by sandy flat coasts, lagoons and offshore islands (for example Djerba).

Waters

The waters of Tunisia are almost all located in the north of the country. The most important river is the Medjerda, it receives the most rainfall (400 mm per year) and carries 82% of the water resources. In addition, there are some smaller wadis, i.e. rivers that do not carry water all year round. The most important lakes, lagoons and sabcha are the lake of Bizerte, the Ichkeul lake, the lake of Tunis, the lagoon of Ghar El Melh, the Sabcha Ariana and the Sabcha Sijoumi.

The center and south of Tunisia are characterized by aridity and lack of runoff. Waters such as the Sabcha Sidi El Héni carry only twelve percent or six percent of Tunisia's water resources, depending on the season. However, large groundwater reserves exist there, which has allowed the area of oases to increase from 15,000 to 30,000 hectares over the last thirty years.

Already during the colonial period, the construction of reservoirs was started, at that time mainly to supply Tunis with drinking water. After independence, the projects were continued, at that time with the aim of irrigation in agriculture. Since the 1980s, urbanization has been responsible for the sharp increase in water demand. Tunisia now has 21 large dams, numerous smaller dams, and 98 wastewater treatment plants. In 2000, 80% of water consumption was used for agriculture. From the year 2030 onwards, serious resource deficits of fresh water are expected.

Climate

In Tunisia, the Mediterranean and arid climates collide. Precipitation decreases from north to south and increases slightly from east to west. A distinction can be made between the north, which is humid in winter and dry in summer, the central Tunisian steppe region, which has a changeable climate with hot summers, cold winters and decreasing precipitation, the Mediterranean coast, which is influenced by the sea and has a more balanced climate, and the desert climate south of the Scotts.

With increasing distance from the Mediterranean, its balancing influence gives way to a continental climate. The average temperature in January is 10 °C, in August 26 °C (Tunis). South of the Atlas, the climate is hot and dry all year round, with very irregular rainfall. Temperatures here reach maximum values of up to 45 °C, with a temperature difference of 10 °C in the shade (normally only 5 °C). The most extreme differences are reached in the Sahara with summer temperatures of 50 °C and ground frosts in winter. Unbearable heat can be brought by the Saharan wind called Shirocco in Tunisia Chehili.

Precipitation falls almost only in the winter months and is mostly brought in by low pressure areas of the west wind drift further north. In summer, the entire country lies in the area of the subtropical high pressure zone, which guides the low pressure areas of the west wind drift around the Mediterranean. However, in exceptional cases, heavy rains can occur even in summer, transforming previously dry wadis into raging torrents. While in the north the annual rainfall is 500 to at most 1000 mm on the north coast and in the mountains, which is sufficient for successful rain-field cultivation, in the south evaporation is stronger than the irregular rainfall of at most 200 mm per year.

| Climate table Tunisia

Source: Climate Tunisia, Weather Tunisia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

flora and fauna

On the north coast and in the Atlas Mountains, Mediterranean deciduous and scrub forest (maquis) grows with holm oak, cork oak and Aleppo pine, where small game as well as wild boar find food. Between 1990 and 2000, the forest cover increased by 0.2 %.

The National Park Djebel Chambi is home to the endangered Cuvier's gazelle as well as the maned sheep. In the adjoining southern steppes and semi-deserts live the Dorkas gazelle and a few specimens of the dune gazelle. Originally, the sabre antelope was also found in these dry zones; it has now been reintroduced in extensive fenced areas in the Bou Hedma National Park. The desert areas are also home to numerous smaller animal species, such as grasshoppers, scorpions, snakes and various bird species. The marshes of the Ichkeul National Park in the north of the country are an important bird sanctuary and are a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Highlands near Metlaoui in central Tunisia

The Chott el Djerid, an important Sabcha

A small lake near Aïn Draham in northwest Tunisia

Satellite image of Tunisia. The vegetation-rich zone in the north, the steppe with the salt plains of the Scotia in the middle and the vegetation-less Sahara in the south of the country are clearly visible.

History

→ Main article: History of Tunisia

Previous story

The first traces of nomadic hunter-gatherers from the Palaeolithic period were found in the oasis of El Guettar, 20 km east of Gafsa.

The Ibéromaurusien, a culture spread along the North African coast, was followed by the Capsien. From this culture, 15,000-year-old skeletons and tools have been found, indicating that Capsien people made needles from bone for sewing clothing from animal skins, in addition to stone tools.

During the Neolithic period, the Sahara was formed with its current climate. This epoch is characterized by the immigration of the Berbers. First contacts were made with the Phoenicians in Tyros, who towards the end of the Neolithic period began to settle what is now Tunisia and later founded the Carthaginian Empire.

Punic and Roman Carthage

Today's Tunisia experienced the establishment of trading settlements by settlers from the eastern Mediterranean at the beginning of historical records. According to legend, the first of these settlements was Utica in 1101 B.C. In 814 B.C., Phoenician settlers coming from Tyros founded the city of Carthage. According to legend, it was Queen Élyssa, sister of Pygmalion, King of Tyr, who founded the city.

Carthage became the largest power in the western Mediterranean within 150 years. The influence happened partly through colonization, but mostly through trade settlements and treaties. This power and the high agricultural potential of the Carthaginian motherland led to the interest of the young, strengthening Roman Empire and confrontation ensued, culminating in the three Punic Wars. Carthage, with its forces led by Hannibal among others, was able to bring the Roman Empire to the brink of defeat several times during the Second Punic War (218-201 BC). At the end of the Third Punic War (149-146 BC), the city of Carthage was besieged for three years and ultimately destroyed. The area of present-day Tunisia became part of the Roman province of Africa, with Utica as its capital. In 44 BC Caesar decided to found a colonia in Carthage, but this was not realized by Augustus until several decades later, and in 14 Carthage became the capital of Africa.

Africa became, along with Egypt, one of the most important suppliers of agricultural products to Rome, especially grain and olive oil. A dense network of Roman settlements developed, whose ruins can still be seen today, such as Dougga (Roman Thugga), Sbeitla (Sufetula), Bulla Regia, El Djem (Thysdrus) or Thuburbo Majus. Africa, together with Numidia, was for six centuries a very prosperous province, where, for example, mosaic art flourished. Thanks to its role as a crossroads of antiquity, Jews and the first Christians subsequently settled in what is now Tunisia.

Christianization

Christianity spread rapidly, especially with the arrival of settlers, traders and soldiers. Carthage became famous in this respect because the influential Christian apologist Tertullian lived and worked here, so that North Africa developed into one of several centres of Christianity in the next period. The pagan population at first resisted the new cult, and later Christianization was enforced by force. From 400 onwards, through the activities of Augustine of Hippo and his bishops, Christianity penetrated all levels of society by bringing the urban aristocracy and landowners over to their side. Crises such as the Donatist church schism, averted by the Council of Carthage, were quickly overcome by Christianity thanks to its good economic and social situation. Ruins of buildings such as the Basilica of Carthage or the numerous churches built on pagan temples (such as in Sufetula) bear witness to this.

On October 19, 439, the Vandals and Alans conquered Carthage and established a kingdom that lasted a century. The Vandals belonged to Arianism, a denomination that had been declared a heresy at the First Council of Nicaea. They demanded loyalty to their faith from the mostly Catholic population and responded to their refusal with violence. Properties of the Catholic Church were confiscated. However, the culture of the local population remained untouched and Christianity also flourished, as far as the new rulers tolerated it. The Vandal Empire declined after the lost battle of Tricamarum, where the Vandals under King Gelimer were defeated by the Eastern Roman forces of Belisar. Emperor Justinian I made Carthage a diocese and in 590 the Exarchate of Carthage, which had high civil and military autonomy from the central imperial power. Pagans, Jews and heretics, however, were soon persecuted by the Byzantine central power, which wanted to raise Christianity to the status of state religion.

Islamization and Arabization

The first Arab advances on what is now Tunisia began in 647. In 661, a second offensive conquered Bizerte; the decision came after the third offensive, led in 670 by Uqba ibn Nafi, and the founding of Kairouan, which later became the starting point for Arab expeditions to the northern and western Maghreb. The death of Uqba ibn Nafi in 693 led only to a temporary halt in Arab conquest; in 695 the Ghassanid general Hassan ibn Numan captured Carthage. The Byzantines, whose naval forces were superior to the Arabs, attacked and captured Carthage in 696, while in 697 the Berbers under al-Kahina defeated the Arabs in a battle. In 698, however, the Arabs again captured Carthage and also defeated al-Kahina.

Unlike previous conquerors, the Arabs were not content to occupy only the coastal areas, but also set about conquering the interior. After some resistance, most Berbers converted to Islam, mainly by joining the armed forces of the Arabs. Religious schools were established in the newly built ribats. At the same time, however, many Berbers joined the Kharijite faith, which proclaimed the equality of all Muslims regardless of race or class. What is now Tunisia remained an Umayyad province until it fell to the Abbasids in 750. Between 767 and 776, the entire territory of Tunisia was ruled by the Berber Kharijites under Abu Qurra, who later had to retreat to their kingdom of Tlemcen.

In 800, the Abbasid caliph Harun ar-Raschid gave his power over Ifrīqiya to the emir Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab and also gave him the right to inherit his function. Thus was founded the Aghlabid dynasty, which ruled the central and eastern Maghreb for a century. What is now Tunisia became an important cultural area with the city of Kairouan and its Great Mosque at its center. Tunis became the capital of the emirate until the year 909.

The Aghlabid emirate disappeared within 15 years (893-909) through the activities of the proselytizing Ismaili Abū ʿAbdallāh ash-Shīʿī, supported by a fanatical army recruited from the Berber Kutāma tribe. In December 909, Abdallah al-Mahdi proclaimed himself caliph, thus establishing the Fatimid dynasty. At the same time, he declared the Sunni Umayyads and the Abbasids usurpers. The Fatimid state spread its influence over the whole of North Africa, bringing under its control the caravanserais and with them the trade routes with Black Africa. A last great revolt of the Kharijite Banu-Ifran tribe under Abu Yazid was put down. The third Fatimid caliph, Ismail al-Mansur, moved the capital to Kairouan and conquered Sicily in 948. In 972, three years after the region was completely conquered, the Fatimid dynasty shifted its base eastward. Caliph Abu Tamim al-Muizz placed the rule of Ifriqiya in the hands of Buluggin ibn Ziri, who founded the Zirid dynasty. The Zirids gradually gained independence from the Fatimid caliph, ending with a complete break with the Fatimids. The latter took revenge for the betrayal by giving Bedouin tribes (the Banū Hilāl and Banu Sulaym) from Egypt property titles to land in Ifriqiya and marching them against the Zirids. Kairouan was subsequently conquered and sacked after five years of resistance. In 1057 the Zirids fled to Mahdia, while the conquerors moved on towards what is now Algeria. The Zirids then unsuccessfully attempted to recapture Sicily, now occupied by the Normans, and for 90 years they tried to regain parts of their former territory. They resorted to piracy to enrich themselves in maritime trade.

This migration was the most decisive event in the history of the medieval Maghreb. It destroyed the traditional balance between nomadic and sedentary Berbers and led to a population intermixing. Arabic, which until then had only been spoken by urban elites and at court, began to influence Berber dialects.

From the first third of the 12th century, Tunisia was subject to frequent Norman attacks from Sicily and southern Italy. The territory of Ifriqiya was simultaneously (1159) conquered from the west by the Almohad Sultan Abd al-Mu'min. Economy and trade flourished; trade relations were established with the main Mediterranean cities. The economic boom caused the Almohad century to go down in history as the golden age of the Maghreb, when great cities with magnificent mosques developed and scientists such as Ibn Chaldūn worked.

The Almohads placed the administration of the present Tunisian territory in the hands of Abu Muhammad Abdalwahid, but already his son Abu Zakariya Yahya I detached himself in 1228 and founded the dynasty of the Hafsids. Thus, between 1236 and 1574, the first Tunisian dynasty ruled. The capital was moved to Tunis, which developed rapidly thanks to maritime trade.

Ottoman rule

From the second half of the 14th century, the Hafsids slowly lost control of their territory and came under the influence of the Merinids of Abu Inan Faris, especially after the lost battle of Kairouan (1348). The plague of 1384 hit Ifriqiya with full force and contributed to the population decline since the invasions by the Banū Hilāl. At the same time, Moors and Jews began to immigrate from Andalusia. The Spanish under Ferdinand II and Isabella I conquered the cities of Mers-el-Kébir, Oran, Bejaia, Tripoli, and the island off the coast of Algiers. The Hafsid rulers felt compelled to enlist the help of the corsair brothers Khair ad-Din Barbarossa and Arudsch.

In their distress, the Hafsids allowed the Corsairs to use the port of La Goulette and the island of Djerba as a base. After the death of Arudsch, his brother Khair ad-Din Barbarossa made himself a vassal of the Sultan of Istanbul and was appointed by him Admiral of the Ottoman Empire. He conquered Tunis in 1534, but was forced to withdraw from the city in 1535 after it was captured by an armada of Charles V in the Tunis campaign. In 1574 Tunis was again conquered by the Ottomans, this time led by Kılıç Ali Paşa. Tunisia thus became a province of the Ottoman Empire. However, the new rulers had little interest in Tunisia and its importance steadily declined at the expense of local rulers; there were only 4000 Janissaries stationed in Tunis. In 1590 there was a Janissary revolt, as a result of which a Dey was placed at the head of the state. A Bey was subordinated to him, who was responsible for the administration of the country and the tax collection. The Pasha, who was equal to the Bey, had only the task of representing the Ottoman Sultan. In 1612 Murad Bey founded the Muradite dynasty, and on July 15, 1705 Husain I ibn Ali made himself Bey of Tunis and founded the Husainid dynasty. Under the Husainids, Tunisia achieved a high degree of independence, although it was still officially an Ottoman province. Ahmad I al-Husain, who ruled from 1837 to 1855, initiated a modernization drive with important reforms such as the abolition of slavery and the adoption of a constitution.

See also: American-Tripolitan War and Second Barbary War

French protectorate, struggle for independence

Economic difficulties caused by a ruinous policy of the Beys, high taxes and foreign influence forced the government to declare state bankruptcy in 1869 and to set up an international British-French-Italian financial commission. Because of its strategic location, Tunisia quickly became a target of French and Italian interests. The consuls of France and Italy sought to take advantage of the Beys' financial difficulties, with France trusting England to remain neutral (England had no interest in Italy taking control of the sea route via the Suez Canal) and also trusting Bismarck to divert France's attention from the Alsace-Lorraine question.

Incursions of plunderers from the Kroumirie into the territory of Algeria provided Jules Ferry with the pretext to conquer Tunisia. In April 1881, French troops invaded Tunisia and within three weeks conquered Tunis without encountering any significant resistance. On May 12, 1881, Bey Muhammad III al-Husain was forced to sign the Treaty of Bardo, making Tunisia a French protectorate. Rebellions around Kairouan and Sfax were quickly quelled a few months later. The Treaty of la Marsa of June 8, 1883, granted France broad powers over Tunisia's foreign, defense, and domestic policies. France thus incorporated the country into its colonial empire and subsequently represented it in the international arena. The Bey had to cede almost all his power to the President General. There was progress in the economic field:

- Banks and companies were established,

- the agricultural area was extended and used for the cultivation of cereals and olives,

- In 1885, considerable phosphate deposits were discovered in the Seldja region. After the construction of some railway lines (see history of railways in Tunisia), phosphate mining and iron ore mining began.

- A bilingual education system was introduced that allowed Tunisia's elites to be educated in Arabic and French.

At the beginning of the 20th century, resistance against the French occupation began. In 1907, Béchir Sfar, Ali Bach Hamba and Abdeljelil Zaouche founded the reformist intellectual movement Jeunes Tunisiens. This nationalist current was manifested in the Djellaz affair in 1911 and in the boycott of the Tunis tramway in 1912. From 1914 to 1921, Tunisia was under a state of emergency and all anti-colonialist press expression was banned. Nevertheless, the national movement became more popular and at the end of the First World War, a group led by Abdelaziz Thâalbi founded the Destur Party. It announced an eight-point programme after its official foundation on 4 June 1920. The lawyer Habib Bourguiba, who had already denounced the protectorate regime in journals such as La Voix du Tunisien or L'Étendard tunisien, founded the journal L'Action Tunisienne in 1932 together with Tahar Sfar, Mahmoud Materi and Bahri Guiga, which advocated secularism as well as independence. This position led to the split of the Destour Party at the Congress of Ksar Hellal on 2 March 1934:

- The Islamist wing stuck with the old name Destour;

- the modernist and secular wing called itself Néo-Destour. It gave itself a modern organization on the model of European socialist parties and decided as its goal to seize power in order to change society.

After the failure of negotiations with the Léon Blum government, some bloody incidents occurred in 1937, culminating in the violently suppressed riots of April 1938. This repression led the Néo-Destour to continue its underground struggle. In 1940, the Vichy regime extradited Bourguiba to Italy at the request of Mussolini, who hoped to weaken the Resistance in North Africa. However, Bourguiba called for support for the Allies on August 8, 1942. Shortly afterwards, the country became the scene of the Battle of Tunisia, at the end of which the Axis troops were forced to surrender at Cape Bon on 11 May 1943.

After the Second World War, armed resistance became part of the strategy for national liberation. Negotiations were held with the French government and Robert Schuman even hinted at gradual independence for Tunisia in 1950; however, nationalist disputes led to the collapse of these negotiations in 1951.

Following the arrival of the new President General, Jean de Hauteclocque, on 13 January 1952 and the arrest of 150 Destour members on 18 January, an armed revolt began as the fronts on both sides hardened. The assassination of trade unionist Farhat Hached by the colonialist extremist organization La Main Rouge led to rallies, riots, strikes and sabotage, with the target increasingly becoming the structures of colonization and government. France mobilized 70,000 troops to bring the Tunisian guerrilla groups under control. This situation was only defused with the assurance of internal autonomy to Tunisia by Pierre Mendès France on 31 July 1954. Finally, on 3 July 1955, the Franco-Tunisian treaties were signed by Tunisia's Prime Minister Tahar Ben Ammar and his French counterpart Edgar Faure. Despite opposition from Salah Ben Youssef, who was subsequently expelled from the Destour Party, the treaties were ratified by the Néo-Destour Congress in Sfax on 15 November. After new negotiations, France recognised Tunisia's independence on 20 March 1956, retaining the military base at Bizerte.

Tunisia after its independence

On 25 March 1956, the country's constituent National Assembly was elected. The Néo-Destour won all the seats and Bourguiba assumed the presidency of parliament. On April 11, he was proclaimed prime minister by Lamine Bey. On August 13, Tunisia's progressive personal status law was enacted. On July 25, 1957, the monarchy was abolished, Lamine Bey was forced to abdicate, and Tunisia became a republic. Bourguiba was elected its first president on 8 November 1959.

The legal basis of the constitution was based on French law. The right of women to vote and stand for election was introduced on 1 June 1959. On the basis of an ordinance, women exercised the right to vote and stand for election in city council elections for the first time in May 1957.

Islam was the state religion (Article 1); however, Tunisia was the only Arab country that had abolished the Islamic legal system of Sharia in its constitution of 1 June 1959. Only article 38 of the Tunisian constitution stipulated that the president must be a Muslim. After independence, women had been given equal rights to men in family law (marriage, divorce, custody). Tunisia had a parliament consisting of two chambers ("bicameral system"):

- The Chamber of Deputies (Chambre des députés) with members elected for five years. The electoral law stipulated that at least 20% of parliamentary seats should go to the opposition, as well as

- The Chamber of Councillors (Chambre des conseillers) (only in existence since 2005) with councillors elected for six-year terms. The councillors were appointed indirectly, i.e. by the Chamber of Deputies, the President or local councillors. The only party represented in this chamber was the RCD. The legislative initiative rested with the President or the 'Chambre des députés'; in practice, it was usually exercised by the President.

In 1958, an international incident with many civilian casualties occurred when the French bombed the border village of Sakiet Sidi Youssef in retaliation against FNL fighters operating from Tunisia as part of the Algerian War. In 1961, with the end of the Algerian War in sight, Tunisia demanded the return of the Bizerte military base. The ensuing Bizerte crisis claimed about 1000 lives, the majority of them Tunisian. It ended with the return of the base on 15 October 1963.

After the assassination of Salah Ben Youssef, the most important opposition figure since 1955, and the banning of the Communist Party on 8 January 1963, the Tunisian Republic became a one-party state led by the Néo-Destour. Its successor, the Constitutional Democratic Collection (RCD), founded in 1988, was also the dominant party until January 2011. It last (2010) sent 152 of the 189 parliamentarians.

In March 1963, Ahmed Ben Salah initiated a socialist policy under which virtually the entire Tunisian economy was nationalized. As early as 1969, however, Ben Salah was dismissed after riots broke out over the collectivization of agriculture; the socialist experiment was thus also ended. The weakening economy and the pan-Arabism preached by Muammar al-Gaddafi led to a political project launched in 1974 to unite Tunisia and Libya under the name of the Arab Islamic Republic. However, this project was dropped after national and international tensions.

The sentencing of Ben Salah to a long prison term ushered in a period in which the liberal wing of the party, now renamed the PSD, led by Ahmed Mestiri, gained the upper hand. Bourguiba was appointed president for life in 1975, the trade union confederation UGTT gained some autonomy during Hédi Nouira's government, and the Tunisian Human Rights League was able to be founded in 1977. The awakening civil society could not be silenced even by the acts of violence against the UGTT on Black Tuesday in January 1978 and the attacks on the mining town of Gafsa in January 1980.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the country entered a political and social crisis, the causes of which were nepotism and corruption, the paralysis of the state in the face of Bourguiba's deteriorating health, succession struggles and a general hardening of the regime. In 1981, the partial restoration of the pluralist system raised hopes, but these were dashed by the rigging of the elections in November of that year. The bloody suppression of the bread riots in December 1983, the renewed destabilization of the UGTT, and the arrest of its chairman, Habib Achour, then contributed to the fall of the aging president and the intensifying rise of Islamism.

On November 7, 1987, Prime Minister Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali deposed President Bourguiba on grounds of senility, a move welcomed by the majority of the political spectrum. In December 1987, Ben Ali dismissed six of the nine Politburo members of the ruling Parti Socialiste Destourien (PSD) and replaced them with personal confidants. After the change of power, several exiled politicians also returned to Tunisia. At the end of 1987, 2500 prisoners, including 600 Islamic fundamentalists, were released from jails. In terms of foreign policy, Ben Ali focused on closer cooperation with the Maghreb states and also resumed diplomatic relations with Libya, which had been broken off in 1985.

Ben Ali was elected on 2 April 1989 with 99.27% of the vote and subsequently managed to revive the economy. Ben Ali actively fought radical Islamism and thus spared Tunisia the violence that shook neighboring Algeria; the Ennahda party was neutralized, tens of thousands of militant Islamists were arrested and convicted in numerous trials in the early 1990s. The leading wing of the Ennahda movement lived in exile in France and Britain. The secular oppositionists founded the Pacte national in 1988, a platform with the goal of democratizing the regime. Meanwhile, the political opposition and nongovernmental organizations began accusing the regime of restricting civil liberties as it expanded repression beyond combating radical Islamism. In the 1994 presidential election, Ben Ali was reelected with 99.91% of the vote; in 1995, he signed a free trade agreement with the European Union. The presidential election of 24 November 1999 was the first pluralist election in the country's history, but was won by Ben Ali with a similar share of the vote as in previous elections. The constitutional amendment of 2002 further increased the scope of presidential power. In the same year, Islamic terrorism made its presence felt with the attack on the al-Ghriba synagogue.

In 2009, Tunisian citizens were severely restricted in their right to vote out the government and their right to freedom of expression. The government introduced severe restrictions on freedom of expression, press and assembly in the run-up to the October 2009 election. Public criticism was not tolerated. There were numerous reports that opposition citizens were targeted for intimidation through criminal investigations, arbitrary arrests, travel restrictions, and controls to prevent criticism. Local and international nongovernmental organizations reported that security forces mistreated detainees. President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali was last confirmed in office in October 2009 with 89.28 percent of the vote; the next presidential election was due to take place in late 2014. Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali was ousted due to public pressure from massive protests beginning in December 2010. After fleeing to Saudi Arabia, parliamentary speaker Fouad Mebazaa temporarily took over on 14 January 2011.

Revolution and new constitution (from 2010)

→ Main article: Revolution in Tunisia 2010/2011

On 4 January 2011, Mohamed Bouazizi, a 26-year-old man, died in a hospital in Tunis from injuries sustained in a self-immolation attack in the provincial capital of Sidi Bouzid on 17 December 2010. The greengrocer had set himself on fire in front of the governorate building to protest the confiscation of his fruit and vegetable stall by police. Solidarity rallies followed throughout the country, which grew into anti-regime rallies. Demands for freedom of the press and freedom of expression mingled with criticism of corruption and censorship. The anger of Tunisians was also directed against the kleptocracy surrounding Ben Ali, especially through the numerous family members of his wife, members of the Trabelsi family, who have taken possession of important companies in Tunisia due to political influence.

During the unrest, a curfew was imposed on the capital and parts of its suburbs in January 2011. President Ben Ali responded to the unrest by declaring a state of emergency. He dissolved the government and announced early elections before fleeing the country on 14 January 2011 in response to increasingly vocal protests. The affairs of state were transferred by the Constitutional Council to Parliament Speaker Fouad Mebazaa on an interim basis, after being briefly led by Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi. The interim government formed by Ghannouchi announced freedom of the press and the release of all political prisoners. On February 3, 2011, in an address to the nation, Interim President Mebazaâ announced the election of a Constituent Assembly to initiate the "final break" with the Ben Ali system. As the "Arab Spring", the Tunisian popular uprising triggered similar movements in almost the entire Arab region, which toppled the rulers in Libya and Egypt, among other places.

On 23 October 2011, the first free elections to a Constituent Assembly took place, from which the Islamist party Ennahda emerged as the strongest with 90 of the 217 seats. The assembly met for the first time on 22 November 2011. With the help of the Congress Party, Moncef Marzouki was elected as the new President of the Republic on 12 December 2011. He appointed Hamadi Jebali as prime minister on 24 December.

Parties represented in the Constituent Assembly included:

- the Islamic-based Ennahda movement with 90 of the 217 seats

- the Social Liberal Congress for the Republic (CPR) with 29 seats

- the populist People's Petition for Freedom, Justice and Development with 26 seats

- the social democratic Democratic Forum for Labour and Freedom (Ettakatol - FDTL) with 20 seats

- the secular and liberal Progressive Democratic Party (PDP) with 16 seats

- the left-wing secular Democratic-Modernist Pole, including the post-communist Ettajdid movement, with five seats

- the party The Initiative, a de facto successor party to the banned RCD, representing the old Ben Ali system, with five seats

- the bourgeois-liberal party Afek Tounes with four seats and

- the Tunisian Communist Workers' Party, with three seats

Even after its victory in the elections to the Constituent Assembly, the Ennahda movement was viewed in different ways: its members were "bourgeois-conservative Muslims," "moderate Islamists" or "militant Islamists. Although Ennahda had always condemned the actions of the Islamists and its election program was written in a moderate way (e.g., gender justice), not a few Tunisians feared that this demand could be discarded as a cover after an election victory.

In 2012/13, there were attacks on MPs and politicians who did not belong to the Ennahda party. The assassination of the left-wing opposition politician Chokri Belaïd on February 6, 2013, a prominent critic of the Ennahda party, and Mohamed Brahmi on July 15, 2013, led to mass demonstrations against the ruling party. After the victory of this party, many women also felt that their rights, which had already been granted to them by Bourguiba in 1956 and Ben Ali afterwards, were endangered. For example, they should no longer be "equal" to men, but should "complement" them (draft constitution of August 2012). There were demonstrations against this into 2013. Prime Minister Jebali had already resigned on 19 February. He was succeeded by the previous interior minister, Ali Larajedh, who made way for Mehdi Jomaâ and his government of technocrats a year later, on 29 January 2014, as part of a national dialogue. Since late 2014, Beji Caid Essebsi was the first democratically elected president of an Arab country; he appointed Habib Essid as prime minister on 5 January 2015. Essebsi died in office on July 25, 2019.

On 7 February 2014, the new constitution, agreed on 27 January by a majority of 200 MPs (out of a total of 216) from almost all parties, was solemnly adopted. It guarantees freedom of belief and conscience, as well as equality between men and women, and was "unique in the Arab world" at the time of its adoption.

The distribution of power between the president and the prime minister is intended to prevent an autocratic regime in the future. A new constitutional court is to be created to monitor the legality of future legislative reforms. This should protect the separation of powers in the future.

One of the biggest points of contention right up to the end was the role of religion in the new Tunisia. While the preamble and Article 1 of the constitution mention Islam without discussing its importance for the state, the text becomes more concrete in some places. Article 6 guarantees freedom of belief and conscience and even - unthinkable in other Arab countries - the right to no belief at all, only to stipulate a half-sentence later that the state protects "the sacred." Islam is the state religion, but the Sharia is not the source of law.

On 1 June 2014, the Truth and Dignity Commission began its work to investigate human rights violations between 1955 and 2013. It presented its final report on 26 March 2019.

Tunisia was the first Arab country to be rated "free" on the Freedom Map by the Freedom House organization in 2015. In 2017, it received a top score of 1 in political rights. In 2015, the Tunisian Quartet was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for its efforts towards democratisation and national dialogue after the revolution.

Women's rights

Equality between women and men was an important theme in the constitution. Advancement of women has been a component of Tunisian policy since the mid-1950s. As early as 1956, after independence, women in Tunisia were largely given equal rights, allowed to vote and file for divorce; only the Islamic law of inheritance, in which sons are entitled to higher shares than daughters, was retained. Meanwhile, the new Articles 20 and 45 not only put men and women on a completely equal footing, but also guarantee equal opportunities and advocate that a certain number of seats on city and county councils be given to women. Nevertheless, 'state feminism' has been criticized by Tunisian women's movements, as discrimination against women persists despite all the state's efforts.

Graffiti under the Tunis city highway

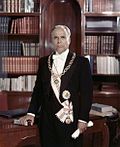

Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, President of Tunisia 1987 to 2011

Habib Bourguiba in Bizerte (1952)

Trial after the Djellaz Affair, 1911

Official photo of Habib Bourguiba

Gold coin of 10 francs from the period of the French protectorate (1891)

Ribat of Monastir

.png)

Redrawing of the burial of a male member of the Capsien culture

Punic stele at Carthage

Archaeological site of Carthage

Search within the encyclopedia