Tuberculosis

![]()

The articles Tuberculosis and Antituberculotic overlap thematically. Information that you are looking for here may also be found in the other article.

You are welcome to participate in

the relevant redundancy discussion or to help directly to merge the articles or to better distinguish them from one another (→ Instructions).

Tuberculosis (Tb or Tbc for short; so named by the Würzburg clinician Johann Lukas Schönlein because of the characteristic histopathological picture, from Latin tuberculosis, from Latin tuberculum 'small lump') is a bacterial infectious disease that is widespread worldwide. The disease is caused by various types of mycobacteria (Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex) and most frequently affects the lungs in humans as pulmonary tuberculosis; in the case of immunodeficiency, there is also increased infestation outside the lungs.

Tuberculosis, which affects about 10 million people worldwide each year, leads the global statistics of deadly infectious diseases. According to the Global tuberculosis report of the World Health Organization (WHO), about 1.4 million people died of tuberculosis in 2015. On top of that, there were 400,000 deaths of additional people infected with HIV. Tuberculosis is (at least nowadays in Germany) most frequently caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, less frequently - in descending order - by Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium africanum or Mycobacterium microti.

The description of the pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis by Robert Koch in 1882 was a milestone in medical history. Tuberculosis is therefore also called Koch's disease. The terms consumption (phthisis or phthisis) or colloquially the moths, white plague and white death are outdated, as are the terms lung ferment, kiln and drying.

Only about five to ten percent of those infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis actually contract the disease in the course of their lives; people with weakened immune systems or genetically determined susceptibility are particularly affected. Transmission usually occurs through droplet infection from sick people in the vicinity. If germs are detectable in sputum, it is called open tuberculosis, and if germs are detected in other external body secretions, it is called potentially open tuberculosis. Coughing produces an infectious aerosol which loses its infectiousness through sedimentation, aeration and natural UV light sources. As cattle can also contract tuberculosis, raw (non-pasteurised) milk used to be a common source of infection in Western Europe and remains so in parts of the world. Because of its transmissibility from animals to humans, tuberculosis is a zoonosis. Conversely, transmission from humans to animals is an important aspect of species conservation of rare primates.

Only with the direct detection of the pathogens or their genetic material is the disease confirmed by laboratory diagnostics. Indirect, i.e. immunological findings or skin tests only contribute to the diagnosis, as they cannot distinguish between a disease and an existing infection. They can also be false-negative in the case of a collapsed immune defence.

Various antibiotics are available for treatment, which are specifically effective against mycobacteria and are therefore also called antituberculotics. In order to avoid the development of resistance and relapses, these must be taken in combination and according to WHO guidelines for at least six months, i.e. long after the symptoms have passed. A vaccination exists, but due to insufficient effectiveness it has not been recommended in Germany since 1998 and is no longer available. Primary prophylaxis with an antituberculous drug is recommended in Germany primarily for children or severely immunologically impaired contact persons. In adults, on the other hand, who have an intact immune system (and are therefore described as immunocompetent), secondary prophylaxis or prevention is only carried out after an infection has been detected by means of preventive administration of antituberculous drugs, taking into account the resistance situation. Tuberculosis is subject to compulsory notification by name in the European Union and in most of the world.

Epidemiology and public health significance

Worldwide

About one third of the world's population is infected with tuberculosis pathogens. However, only a small proportion of infections lead to disease. According to the WHO tuberculosis report (Global tuberculosis report 2016), there were 10.4 million new infections and 1.8 million deaths worldwide in 2015. Both figures have been falling steadily since 1990.

Treatment options are often inadequate, as they require expensive antibiotics, take a long time and are often impracticable given the social circumstances of those affected. Laboratories for diagnosis and treatment are also often lacking in affected regions. In Eastern Europe in particular, poverty and deficiencies in the health system have led to a worrying increase in tuberculosis, especially with multi-resistant strains of the pathogen. Worldwide, too, the disease is increasingly being caused by such drug-resistant tuberculosis strains.

Tuberculosis infection is particularly problematic in HIV-infected persons with manifest AIDS. Due to the immunodeficiency, HIV increases the probability of the outbreak of a tuberculosis disease many times over. In Africa, tuberculosis is the most common cause of death along with AIDS. Both diseases occur in close correlation with each other, especially among inhabitants of metropolitan slums. In this context, immunodeficiency due to HIV often leads to negative results in routine tuberculosis tests, although the disease is present (see also errors of the 1st and 2nd kind). This is due to the fact that the skin tests (tuberculin test, Tine test) check the immunological reaction to pathogen components, but this is inhibited by AIDS. The course of tuberculosis is then considerably accelerated. In poor countries, TB is considered a sign of the onset of AIDS and leads to death in the majority of HIV patients. The WHO therefore calls for and promotes worldwide coordination of tuberculosis and AIDS research.

Surprisingly, an Italian study found a prevalence (disease frequency) of latent tuberculosis infections of nine percent among healthy health care workers and 18 percent among just over 400 people suffering from psoriasis. Also 30 percent of the sick with pneumonia and lung cancer were latently infected.

Germany, Austria and Switzerland

In 2016, 5915 tuberculosis patients were reported to the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) in Germany, including 233 children under the age of 15 (2005: 230). In 2016, there were 7.2 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in Germany. Official statistics gave 100 deaths in 2015. The data probably do not quite correspond to the real figures, as the number of unreported cases of this disease is relatively high due to its non-specific symptoms. According to a pathology study from Germany, only one third of post-mortem tuberculosis cases were diagnosed during life.

In Germany, the disease is particularly prevalent in Hamburg, Bremen and Berlin. Among people born in the country, the older age groups predominate due to the tendency to activation and reactivation as a result of the declining immune defence. Among migrants, the middle age cohorts predominate, as fresh infections are more likely to trigger the disease here. The preliminary tuberculosis statistics for 2017 show a plateau in Germany at the level of 2016, after an increase in tuberculosis cases due to increased immigration in autumn 2015. In Switzerland and Austria, the number of cases also decreased slightly in 2017. A feared stronger increase in the number of cases due to the wave of migration in 2017 has therefore not yet occurred.

In Austria, 583 cases of tuberculosis were recorded in 2015, while Switzerland recorded 546 cases in the same year.

The following table shows the number of new cases per 100,000 inhabitants (incidence) and the number of new cases per year in Germany (D), Switzerland (CH) and Austria (A).

| Year | Incidence | Reported cases (new cases) D | Incidence | Reported cases (new cases) CH | Incidence | Reported cases (new cases) A | Incidence |

| 1940 | 156,8 | 109,508 (Imperial territory) | approx. 100 | 3.127 | only figures for the territory of the Reich | ||

| 1950 | 277 | 137,721 (Germany only) | 68,1 | approx. 8200 | approx. 500 | ||

| 1960 | 126,6 | 70,325 (Germany only) | approx. 40 | approx. 4600 | approx. 210 | ||

| 1970 | 79,3 | 48,262 (Germany only) | approx. 25 | 2.850 * | approx. 80 | ||

| 1980 | 42,1 | 27,845 (Germany only) | approx. 20 | 1.396 | 2.191 * | ||

| 1990 | 19,6 | 12,184 (only FRG) | 18,4 | 1.278 | 20,4 | 1.521 * | |

| 2000 | 11,0 | 9.064 | 8,7 | 629 | 15,3 | 1.226 | |

| 2006 | 6,5 | 5.402 | 6,9 | 520 | 10,8 | 894 | |

| 2007 | 6,1 | 5.020 | 6,3 | 478 | 10,7 | 891 | |

| 2008 | 5,5 | 4.543 | 6,7 | 520 | 9,9 | 817 | |

| 2009 | 5,4 | 4.444 | 7,1 | 556 | 8,4 | 697 | |

| 2010 | 5,4 | 4.388 | 6,9 | 548 | 8,2 | 688 | |

| 2011 | 5,3 | 4.317 | 7,1 | 577 | 8,2 | 687 | |

| 2012 | 5,2 | 4.220 | 5,7 | 463 | 7,7 | 648 | |

| 2013 | 5,3 | 4.318 | 6,5 | 526 | 7,7 | 649 | |

| 2014 | 5,6 | 4.488 | 5,7 | 473 | 6,8 | 582 | |

| 2015 | 7,3 | 5.865 | 6,4 | 546 | 6,7 | 583 | |

| 2016 | 7,2 | 5.915 | 7,2 | 611 | 7,2 | 634 | |

| 2017 | 6,7** | 5.476** | 6,3** | 536** | 6,5** | 569** | |

| 2018 | 6,5 | 5.513 | |||||

| 2019 | 4.735 |

* contagious only ** provisional figures

Pathogen of tuberculosis

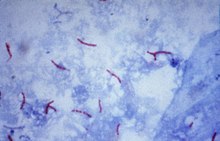

The main causative agent of tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is an aerobic gram-positive rod bacterium that divides every 16 to 20 hours. Compared to other bacteria that have division rates in the range of minutes, this is extremely slow. Microscopic detection is successful due to the typical staining characteristics: The bacterium retains its staining after treatment with an acidic solution and is therefore called an acid-fast rod. In the most common stain of this type, the Ziehl-Neelsen stain, the red stained germs stand out against a blue background. Detection is also possible by fluorescence microscopy and by auramine-rhodamine staining. In the Gram stain, mycobacteria hardly present themselves, but the structure of the peptidoglycan strongly resembles that of Gram-positive bacteria, so that M. tuberculosis is formally classified as Gram-positive. This was confirmed by sequence analyses of the RNA.

The same group of bacteria includes other mycobacteria, which are also counted among the causative agents of tuberculosis: M. bovis, M. africanum and M. microti. These pathogens are found only sporadically in tuberculous diseases in Germany. M. kansasii and also M. avium can in rare cases, like a number of other mycobacteria, cause tuberculosis-like clinical pictures. However, atypical mycobacteria other than tuberculosis (MOTT) do not usually pose a risk of infection.

M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. africanum, M. microti, M. canetti, M. pinnipedi, M. caprae and the vaccine strain Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) are grouped together as the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex.

Electron micrograph of the tubercle bacilli

Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Ziehl-Neelsen stain (acid-fast rods)

Questions and Answers

Q: What is Tuberculosis?

A: Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by bacteria.

Q: What is it caused by?

A: It is caused by several types of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Q: What did people call it in the past?

A: In the past, people called it consumption.

Q: What part of the body does the disease usually attack?

A: The disease usually attacks the lungs.

Q: Can Tuberculosis affect other parts of the body?

A: Yes, it can also affect other parts of the body.

Q: What type of bacteria usually cause Tuberculosis?

A: Usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis causes Tuberculosis.

Q: What is the nature of Tuberculosis?

A: Tuberculosis is an infectious disease that can cause severe illness and even death if not treated properly.

Search within the encyclopedia