Tuatara

![]()

Tuatara is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see Tuatara (disambiguation).

The tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) is the only recent species of the family Sphenodontidae. Found only on New Zealand islands, these animals are often referred to as "living fossils" because they are survivors of a relatively diverse group, the Sphenodontia, whose heyday dates back more than 150 million years. Basic morphological peculiarities compared to other recent representatives of the reptiles, especially the presence of a lower temporal arch, which has a name-giving meaning as a "bridge" and distinguishes them from the habitus of quite similar pangolins (Squamata), justify, according to current opinion, the classification in a separate order (Sphenodontia, also called Rhynchocephalia). In contrast to many other reptiles that are warm to the touch, they are active even at low temperatures and are able to actively search for prey such as arthropods or birds' eggs despite their significantly lower body heat. In contrast to their morphology, relatively little is known about the lifestyle of the endangered tuataras.

Etymology

The genus name Sphenodon is composed of the ancient Greek words σφήν sphén, German 'wedge' and ὀδούς odous, German 'tooth'. The species epithet punctatus is Latin for 'dotted'. The trivial name "Tuatara" is from the Maori language, meaning 'spiny back', and refers to the spiny dorsal crest of the animals. The German trivial name 'tuatara' was introduced in 1868 by Eduard von Martens. It refers to the two complete 'bone bridges' (temporal arches) in the fenestrated posterior part of the skull of these animals (see → Skeleton).

Morphology

Tuataras grow to an average length of 50 to 75 centimetres and weigh about one kilogram, with males being slightly larger. They are powerfully built, plump lizards with a dorsal crest of elongated horn platelets. The fore skull is slightly elongated like a beak. They have a greyish ground colour.

Skin

The skin of tuataras is similar to that of pangolins. The hypodermis has mostly horizontally running connective tissue fibers and lies loosely on the underlying musculature. The dermis is very thick and has larger connective tissue fiber bundles. Under the dermis lies the bulk of the large, branched chromatophores. Their granular, black to brown pigment content can cause a physical color change through contraction and expansion. Although smaller there, the chromatophores can be traced into the stratum corneum. Dorsally the epidermis forms several granular scales, which reach their maximum size at the toes. Along the body sides arranged skin folds carry pointed tubercle scales. The scaling of the ventral side consists of nearly square scales. A ridge of spiny scales runs from the occiput across the dorsal side of the body and is higher in males. Bridge lizards molt only once or twice a year.

Skeleton

The diapsid skull of tuataras differs fundamentally from the skull of other pangolins in the presence of two fully developed temporal arches. Thus, it does not have the "push rod system" that characterizes the relatively strongly mobile (kinetic) skull of the other scaled lizards. This is one of the reasons why the tuataras are placed in their own subgroup of the scaled lizards, the Sphenodontia. In fact, the skull of the tuataras is akinetic, which means that the upper jaw and the palatal roof are not movable against the cranium. However, articulations between cranial components are still found in embryos, so the rigid skull of adult tuataras is often interpreted as an adaptation to the burrowing lifestyle and diet. Also related to the lifestyle are two bony, downward projections at the anterior end of the premaxillary (part of the maxilla), which have functional "incisors" attached to them, giving the snout portion of the skull its typical hooked-beak appearance when viewed from the side. The dentition is acrodont, meaning that the teeth are fused to the upper edge of the jaw. Bridget lizards therefore lack any alternation of teeth, which means that conclusions about age can be drawn from the condition of the teeth. In old tuataras, only one chewing ridge remains. On the outer edges of the palatine bones there is a row of eleven or twelve teeth parallel to the posterior teeth of the maxillaria. Older males may have an additional one or two teeth on the ploughshare bone. At the anterior end of the dentale (tooth-bearing part of the mandible) there is a kind of canine tooth, which is very different from the pointed-saw-shaped row of teeth present there. When biting down, the row of teeth of the lower jaw exactly fits into the gap between the maxillary and palatal row of teeth. Since tuataras can push their lower jaw forward and backward and thus cut ("saw") the prey instead of tearing it, it is possible for them to crack hard chitinous shells of large insects and to cut small lizards.

Unlike the pangolins, tuataras lack the seventh element of the lower jaw, the splenial. Particularly striking on the skull of tuataras is a large parietal hole (foramen parietale) for the parietal eye. The triangular quadratum, formed as a thin plate of bone, is perpendicular to the median plane of the skull and is reinforced dorsally by the wing bone and squamosum. Ventrally, the quadratum, together with the quadratojugale, forms an articular surface for the articulating element (articulare) of the mandible.

The postcranial skeleton (skeleton without skull) of tuataras is characterized by a vertebral column with 27 precaudal (anterior to the tail) vertebrae consisting of 8 cervical, 17 trunk, and two cruciate vertebrae. Characteristic of the first cervical vertebra (atlas) is a rudiment of the proatlas. As in some other pangolins, the tail can be shed for self-protection (autotomy), the regenerate being supported by a transparent-appearing cartilaginous rod. From the fourth cervical vertebra, tuataras have short cervical ribs. The ribs of the trunk in tuataras have cartilaginous, wing-like broadenings. These overlap to form a type of armor for the abdominal cavity. The ninth to twelfth torso ribs are attached to the sternum at the bottom.

Nervous system

The brain of tuataras is much smaller than the volume of the skull surrounding it, and much more primitive than the brains of other pangolins. The terminal brain continues into very long olfactory tracts that terminate in thick olfactory bulbs. The midbrain roof (tectum mesencephali) is much lower than in pangolin creepers. Fifth, seventh, eighth, ninth and tenth cranial nerves are very similar in location to those of amphibians and fish.

A special sensory organ, the parietal eye, they share only with a few other reptiles and lampreys. It has a lens-like epithelial layer, which is followed by a basal, retina-like part. A thin parietal nerve conducts sensory stimuli to the diencephalon. With this sensory organ they can only perceive brightness, but probably more finely than "normal" eyes. In addition, the parietal eye could serve to regulate the heat balance.

The large eyes of tuataras sit in a corresponding eye socket. Unlike in pangolins, the retractor bulbi muscle has two attachments to the eyeball. It lacks a lacrimal gland to moisten the outer eyes, but tuataras have a functional Harder's gland behind the eyeball that produces an oily secretion to keep the nictitating membrane lubricated. Excess moisture is drained by means of lacrimal tubules and nasolacrimal duct leading into the nasal cavity. Both eyelids are present, but the lower one is much larger and more developed. The transparent nictitating membrane is connected by a nictitating tendon to the so-called bursalis muscle, which moves the nictitating membrane. The slit-shaped pupil, usually due to light incidence, is not an indication of pure nocturnal activity, but of hunting activity, which is mainly nocturnal. The retina does not contain rods and cones, but two different types of cones, whereby the animals can see very well during the day and at night, but color vision is not or only rudimentarily present. Behind the retina there is a layer of cells called tapetum lucidum, which functions as a residual light amplifier by reflecting the light passing through the retina.

The nose of tuataras has a second larger extension behind the nasal vestibule (vestibule nasi).

The taste buds of tuataras are located primarily on the palatal mucosa. The tongue, which is not split, is not used for licking and thus for chemosensory orientation, unlike in quite a few other reptiles (see also Jacobson's organ).

Although tuataras have no external ear opening and no superficial eardrum, they hear well. The spacious middle ear communicates with the pharyngeal cavity via the eustachian tube. The rest of the structure is essentially identical to that of the pangolin.

Circulatory and metabolic system

The heart of tuataras, which consists of a venous sinus, a ventricle (ventriculus cordis) and two atria (atria), is characterized by its widely advanced position at the level of the shoulder girdle. Three vena cavae open into the sinus venosus. The atria appear as a unitary sac when viewed from above, but they are completely separated internally by a well-developed atrial septum. The ventricle, separated from the atria by a distinct coronary groove (sulcus coronarius), is thick-walled and muscular; internally it has hardly any septa, a plesiomorphy. Other features include a well-developed ductus caroticus and ductus arteriosus on each side and the origin of the right and left carotid arteries from a right aortic arch. The origin of the laryngeal artery from the pulmonary arch is also a plesiomorphy, as are the previously mentioned special vascular systems.

The respiratory apparatus of the tuataras is primitive. The larynx is formed by an unpaired cricoid cartilage and a paired stellate cartilage, the trachea is supported by cartilaginous clasps. The trachea leads by a short bronchus on either side into the two lungs, which are merely thin-walled sacs. The inner surface of the two lungs is covered by a network of honeycomb-like spaces, which become larger towards the back. With the help of the laryngeal cartilages, the otherwise mute animals can produce sounds when exhaling to defend themselves against enemies and to communicate with conspecifics.

The simply built digestive system of the tuataras consists, among other things, of a widely expandable esophagus, which leads into the long, spindle-shaped stomach. The small intestine lies in two to three loops in the right part of the abdominal cavity. The large intestine opens into the fecal space (coprodaeum) of the cloaca.

The left kidney in tuataras is almost twice as large as the right. One short ureter each opens into the urinary cavity (urodaeum) of the cloaca. These orifices are common with the vas deferens in males, but separate from the oviduct in females.

Sex organs

Especially the internal sex organs show no particular specialization. Although females have the ability to store sperm, no special organ for this can be found. Males lack a copulatory apparatus, an unpaired penis is secondarily lost, paired hemipenes as in pangolins are also not present in embryonic stages. Both sexes sometimes have anal glands interpreted as hemipenis homologues, which probably produce sebum.

tuatara

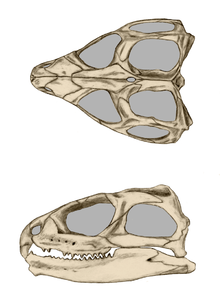

Dorsal and lateral views of the skull of a bridging lizard. Schematic. The upper of the two temporal windows is only narrowly visible in the lateral view.

Questions and Answers

Q: What are the Tuatara?

A: The Tuatara are reptiles which resemble lizards.

Q: What is unique about the Tuatara?

A: The Tuatara have two rows of teeth in their upper jaw which overlap one row on the lower jaw, a pattern which is not present in other living species.

Q: How many species of Tuatara are there?

A: There are two species of Tuatara.

Q: Where do Tuatara live?

A: Tuatara are endemic to New Zealand, meaning they only live there.

Q: What are the closest living relatives of the Tuatara?

A: The closest living relatives of the Tuatara are lizards and snakes.

Q: What is the significance of the spiny crest on the Tuatara?

A: The spiny crest along the back of the Tuatara is what the Maori word "Tuatara" refers to. It is more pronounced in males.

Q: When did the Tuatara order of reptiles flourish?

A: The Tuatara order of reptiles flourished around 200 million years ago.

Search within the encyclopedia