Truth

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Truth (disambiguation).

The concept of truth is used in various contexts and understood in different ways. In general, the conformity of statements or judgments with a fact or reality in the sense of a correct representation is referred to as truth. In addition, "truth" is also understood as the agreement of a statement with an intention or a certain meaning or a view normatively distinguished as correct ("truism" or commonplace) or with one's own knowledge, experiences and convictions (also called "truthfulness"). Deeper considerations see truth as the result of a revealing, uncovering or discovering process of recognizing original connections or essential features.

The underlying adjective "true" can also describe the genuineness, correctness, purity or authenticity of a thing, an action or a person, measured in terms of a particular concept ("A true friend"). In everyday language, "truth" can be distinguished from a lie as the deliberate utterance of untruth and from an error as the falsified assertion of truth.

The question of truth belongs to the central problems of philosophy and logic and is answered differently by different theories. Roughly, the questions of a definition of truth and of a criterion for whether something is rightly called "true" can be distinguished. In certain formal semantics, truth values are assigned to propositions that describe their being true in certain contexts. The concept of provability, which is important for the foundations of mathematics, for example, can sometimes be associated with such semantic concepts of truth; a proof then demonstrates the truth.

In science and technology, truth (true value) is fundamentally sought by means of measurement. True values are not directly measurable, but are successfully delimited by value intervals (of the complete measurement result).

Walter Seymour Allward, Veritas, 1920

Word Origin

Truth is formed as an abstractive to the adjective "true", which evolved from the Indo-European root noun (ig.) *wēr- "trust, faithfulness, agreement".

Truth in philosophy

The concept of truth in the philosophy of antiquity corresponds to ancient Greek ἀλήθεια - aletheia and Latin veritas. In modern theoretical approaches, "truth" usually denotes a property of beliefs, opinions, or utterances, which may refer to any possible sphere of knowledge (everyday objects, physics, morality, metaphysics, etc.).

A limitation of the reference of truth-capable propositions to certain object areas, e.g. to the area of those objects that are accessible to experience, is controversial, as is the exact determination of the objects to which this property is attributed (the "truth-bearers": judgements, beliefs, statements, contents etc.). But also the nature of truth as a property of truth-bearers is subject to debate (e.g. correspondence to "truth-makers", i.e. objects, facts, etc., or "coherence" as correspondence to other truth-bearers). Also debatable is how we obtain knowledge of this property: only through empirical acquisition of knowledge or, at least for certain objects, also in advance, "a priori".

Different elaborations of truth theories answer some or all of these questions in different ways.

Schematic overview

| Position | Truth definition | Truth Bearers | Truth criterion |

| Ontological-metaphysical correspondence theory | "Veritas est adaequatio intellectus et rei" | Think | things in the world |

| Dialectical-materialistic theory of reflection | Consistency between consciousness and objective reality | Consciousness (orthodox Marxism) | Practice |

| Logical-empirical picture theory | Conformity of the logical structure of the sentence with that of the facts it depicts | Sentence structure | Structure of the facts |

| Semantic theory of truth | "x is a true statement if and only if p" (For "p" insert any statement, for "x" insert any proper name of that statement). | Record (of the object language) | Discourse universe (of the object language) |

| Redundancy theory | The term truth is used only for stylistic reasons, or to lend emphasis to one's own assertion. | Records | - – |

| Performative Theory | what you do when you say a statement is true... | Action / Speech act / Commitment | own behaviour |

| Coherence theory | Freedom from contradiction / derivation relations of a statement to the system of accepted statements | Statement | No contradiction of statement and already accepted statement system |

| Consensus Theory | discursively redeemable validity claim, which is connected with a constitutive speech act | Statement/Proposition | justified consensus under conditions of an ideal speech situation |

The correspondence theory of truth

The theory of truth that dominated for long periods in the history of philosophy was the correspondence or adequation theory of truth. This theory assumes truth as the correspondence of mental ideas with reality. Its representatives understand truth fundamentally as a relation between two reference points and designate these as correspondence, correspondence, adequation, agreement, etc. The relations are also defined in different ways. The relations are also defined differently: anima(soul)/ens, thinking/being, subject/object, consciousness/world, cognition/actuality, language/world, assertion/fact etc.

The approximately opposite view is that of ancient skepticism, which questions the possibility of an assured, demonstrable knowledge of reality and truth.

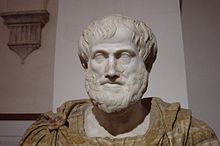

Aristotle

Aristotle is often cited as the first correspondence theorist, who formulated in his Metaphysics:

"For to say that the being is not or the not-being is is false; on the other hand, to say that the being is and the not-being is not is true. He, therefore, who predicates a being or not-being, must pronounce true or false.

[...] For it is not because our opinion that you are white is true that you are white, but because you are white that we say the truth in asserting

this."

However, Aristotle does not speak of correspondence or adequation in this famous formulation. Therefore, there is no scientific consensus on the assignment of Aristotle to the theory of correspondence.

Thomas Aquinas

Within medieval philosophy, Thomas Aquinas is one of the best known proponents of a correspondence or adequation theory of truth. In the Quaestiones disputatae de veritate, the classic formulation of the ontological correspondence theory of truth is found as "adaequatio rei et intellectus (agreement of the thing with the intellect)":

| "Respondeo dicendum quod veritas consistit in adaequatione intellectus et rei [...]. Quando igitur res sunt mensura et regula intellectus, veritas consistit in hoc, quod intellectus adaequatur rei, ut in nobis accidit, ex eo enim quod res est vel non est, opinio nostra et oratio vera vel falsa est. Sed quando intellectus est regula vel mensura rerum, veritas consistit in hoc, quod res adaequantur intellectui, sicut dicitur artifex facere verum opus, quando concordat arti." | "I answer that it is to be said that truth consists in the correspondence of understanding and thing [...]. Therefore, if things are the measure and guide of the understanding, truth consists in the understanding's conforming to the thing, as is the case with us; for on the basis of the thing being or not being, our opinion and speech of it is true or false. But if the understanding is the guide and measure of things, truth consists in the conformity of things to the understanding; so the artist is said to make a true work of art if it conforms to his idea of art." |

The background of this definition of truth is a threefold understanding of truth:

- from the side of agreement (ontological truth);

- from the side of the cognizing subject, whose knowledge agrees with what exists (logical truth) - expressed in the formula "adaequatio intellectus ad rem".

- from the side of the cognized object, whose being agrees with the knowledge of the cognizing subject (ontic truth) - expressed in the formula "adaequatio rei ad intellectum".

Modern times, Kant

A correspondence-theoretical concept of truth was very often advocated until the 19th century. In the Critique of Pure Reason, for example, Kant declares: "The name explanation of truth, namely, that it is the correspondence of cognition with its object, is here given and presupposed" (A 58 / B 82). Kant himself, however, advocates a more differentiated theory of truth, which depends on the source of the respective cognition. Thus, for individual judgments about objects of experience, he advocates verificationism (correspondence between experience and thought), but this can be limited or even nullified by the conditions of coherence of experience. For general judgements of experience and laws of nature a moderate fallibilism.

Neuthomism

In more recent philosophy, the theory of correspondence is defended above all by the neo-Thomists (Emerich Coreth, Karl Rahner, Johannes Baptist Lotz). There, truth generally denotes a relation of correspondence between the knowledge of a cognizing subject and a being to which this knowledge refers. Coreth defines truth in a typical formulation as "correspondence between the knowledge and the being". The background is formed by the conception of a fundamental identity of being and knowledge: "Being is originally and actually knowing oneself, knowing being-with-itself in the spiritual consummation".

Dialectical-materialistic theory of reflection

With dialectical materialism, Marx formulates a theory of reflection for the representation of objective reality (Wirklichkeit) in the consciousness of human beings. According to this, truth is a correspondence of consciousness with objective reality. It is in the service of practice and is measured by that alone. Marx expresses this in his second thesis on Feuerbach:

"The question of whether human thought is endowed with objective truth is not a question of theory, but a practical question. In practice man must prove the truth, i. e. reality and power, this-ness of his thinking. The dispute about the reality or non-reality of thought - which is isolated from practice - is a purely scholastic question."

While in orthodox Marxism consciousness is assumed to be the "image" of the state of affairs, more recent directions are moving towards attributing this function to linguistic entities such as propositions:

"It [truth] is defined as the property of statements to agree with the facts reflected."

Truth always represents a relation - namely the relation of the object depicted in consciousness and the object itself. If the reflection is adequate, one speaks here of (relative) truth. The criterion for this is practice. Dialectical materialism distinguishes relative truth from absolute truth. Both are regarded as a dialectical unity: According to it, an absolute truth is, for example, the descent of man from the animals. The relativity of this truth results, e.g., from the development of the knowledge of mankind, which comprehends the processes of nature more and more perfectly and thus finds out "new", more exact, higher truths. Darwin's thesis is considered to be absolutely true, but it can be supplemented and determined more and more precisely. Accordingly, people attain a higher and higher relative truth on the basis of absolute truths. There is no final, eternal truth in dialectical materialism.

Logical-empirical picture theory

Within logical empiricism, too, there is an image theory of truth. This is classically elaborated in the work of the early Wittgenstein. In the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Wittgenstein begins by assuming that we make images of reality. They are a "model of reality" (2.12). Images are expressed in thoughts, the shape of which is "the sensible proposition" (4).

Wittgenstein defines reality as "the totality of facts" (1.1). Facts are existing states of affairs, to be distinguished from mere non-existing states of affairs (2.04-2.06). They consist of objects or things and the connection between them (2.01). The proposition is also a fact (3.14). A fact becomes a picture by virtue of the "form of the depiction" that it has in common with the thing depicted. Wittgenstein tries to make this clear with the following example:

"The gramophone record, the musical thought, the musical notation, the sound waves, all stand in that mapping relation to each other which exists between language and the world."

- Ludwig Wittgenstein: Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. 4.014.

Just as musical notation is a picture of the music represented by it, the sentence represents "a picture of reality" (4.021). A sentence consists of names and the relations between them. It is true if the names it contains refer to real objects and the relation between the names corresponds to that between the objects referred to.

Problems of the correspondence theory

In correspondence theory, truth is thought of as a two-digit relation of the form aRb. In all these three structural moments, problems arise which were increasingly thematized at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, leading to the development of alternative theories of truth.

Thus there are difficulties in determining the truthbearer. What are the objects or entities that are supposed to correspond to facts or reality and that we call true in this sense?

On the other hand, there is the question of the truthmaker, namely, of what kind is that with which statements must agree in order to be true. Although there is widespread agreement among correspondence theorists that truthmakers are facts, there is disagreement about what facts actually are. Günther Patzig, for example, expresses a widely held view in analytic philosophy that one can neither define the general concept of fact nor identify individual facts without recourse to propositions. Facts would therefore have to be regarded as fulfilled truth-conditions of propositions. For the correspondence theory, this results in the dilemma that it gets into a definitional circle, since the concept of fact already contains the concept of truth, which actually has to be defined first:

"In this connection it is important to see that it is at first quite unclear whether what are facts are to be explained via W.[ahrheit], or whether W.[ahrheiten] are to be explained via facts. Precisely for this reason, a definition according to which what is true is what agrees with facts is as correct as it is empty: it is a tautology [...]."

The third problem concerns the correspondence relation itself. This is already evident from the fact that a variety of expressions have been used to describe it in the various theories: Correspondence, correspondence, agreement, adequation, mapping or reflection.

Against the concept of a genuine figurative relation there was the objection that it remained unclear how the correspondence relation of two such different "entities" as knowledge and object should be thought at all (e.g. between my knowledge that the concrete object in front of me is red and the object itself). In order to circumvent these difficulties, representatives of linguistic-analytically oriented theories of correspondence tried to conceptualize the relation between propositions and facts more abstractly as a structural equality or isomorphism. However, even this concept proves to be problematic in the case of simple examples, since in many cases an unambiguous decomposition of a fact into its elements does not seem to be possible:

"Let us take the example that has long been notorious in the discussion of truth: the cat is on the mat. This statement can perhaps still be broken down into its constituent parts in a halfway plausible way. But what about the corresponding fact? Can one really say that this fact consists of the and the constituent parts, such as the cat, the mat, and a certain spatial relation?"

One encounters even greater difficulties, for example, with negative statements and their counterpart on the side of facts. What is the agreement, for example, if I recognize that a certain object does not exist or that it does not have certain properties? How is one to think of a correspondence with something that does not exist? It is even more difficult to interpret unreal conditional sentences such as, "If I had not done this, that (perhaps) would not have happened."

Nevertheless, Karen Gloy is to be agreed: "The adaequatio understanding of truth is undoubtedly the most familiar and widespread, dominating our everyday, pre-scientific thinking as well as our scientific one." In everyday life, talking (vaguely) about the correspondence of a linguistic statement to an objective fact often poses no problem.

Linguistic-analytically oriented theories of truth

With the rise of linguistic analytic philosophy, the 20th century saw a resurgence of interest in the problem of truth. The concept of truth was partly developed within highly complex theories of truth. The positions represented differ both with regard to the question of which "objects" can be ascribed the predicator "true" and with regard to the criteria as to when truth can be spoken of.

In these theories, truth is no longer conceived as a property of consciousness or thought, as in the correspondence theory, but as a property of linguistic entities such as sentences or propositions.

Semantic theory of truth

The most influential language-analytically oriented theory is Alfred Tarski's semantic theory of truth (also logical-semantic or formal-semantic theory of truth). Tarski's aim is a definition of truth following the usage of colloquial language and in specification of the correspondence theory. Furthermore, he additionally states how and under which conditions a given expression can be proved to be true.

For Tarski, the concept of truth always refers to a particular language. To avoid antinomies, Tarski proposes to reserve semantic predicates such as "true" or "false" for a respective metalanguage. In this metalanguage, "true" or "false" are supposed to denote statements formulated in an object language separate from the metalanguage. Since for each language L the predicate "true in L" is to be banished from L itself, a hierarchization of languages occurs for which truth predicates can be defined without contradiction.

On the basis of the classical concept of truth, Tarski assumes that propositions of the type should follow from an adequate definition of truth:

"The statement 'snow is white' is true exactly when snow is white."

Or generalized to a scheme:

"(T) X is true exactly if p."

According to Tarski, this "equivalence of form (T)" is not a definition of truth, since there is no statement here, but only the scheme of a statement:

"We can only say that any equivalence of the form (T) which we obtain after substituting for 'p' a particular statement and for 'X' the name of that statement may be regarded as a partial definition of truth, explaining wherein the truth of that one individual statement consists. The general definition must in a certain sense be the logical conjunction of all these partial definitions."

For his formal definition, however, Tarski then first starts from the notion of fulfillment. In logic, a subject fulfils a propositional function if the function becomes true by inserting the name of the subject. So here the notion of fulfillment is defined by means of the notion of true. This definition can be turned around and for propositional functions with only one free variable we can say: A proposition is true, if its subject fulfills the propositional function. But the term "fulfillment" must now be defined without recourse to the term "true" in order to avoid a circle. According to Tarski, this is again possible with the help of a schema: a subject fulfils a propositional function if it has the property expressed in the predicate, thus:

"for any a - a satisfies the propositional function x if and only if p".

Appropriate insertions give rise to statements which clarify the notion of being fulfilled and can be regarded as partial definitions of this notion. For an example related to colloquial language, we can, for instance, substitute for "x" the quotation ""x is white"" of the propositional function "x is white" and for "p" the propositional function "a is white", which arises by substituting "a" for "x", to obtain the following statement:

"for any a - a satisfies the propositional function "x is white" if and only if a is white"

The given scheme can be generalized for propositional functions with several free variables or without free variables and can be specified for a large class of formal languages in such a way that first a definition of satisfiability and then one of truth can be established.

According to Tarski, in order to prove the truth of a concrete proposition, one starts from a list of fundamental statements that are assumed to be fulfilled. These fundamental statements are axioms or observational data that represent the connection to reality. If, with the help of logic, it is possible to derive the proposition in question from the fundamental statements, it is also fulfilled.

For Tarski, a general definition of truth is only possible within the framework of formal languages. In normal language, it can only ever be clarified "in what the truth of this one individual statement consists." So also in his example that has become famous: "'It is snowing' is a true statement if and only if it is snowing." He says, however:

"The results obtained for formalized languages also have some validity with respect to colloquial language, thanks to the universalism of the latter: by translating any definition of a true statement [...] into colloquial language, we obtain a fragmentary definition of truth."

Apparently, this definition refers to a correspondence between statement ("it snows") and fact ("when it snows"), so that it is often assumed that Tarski's logical-semantic concept of truth proceeds from the idea of correspondence. While this may correspond to Tarski's aim, a specification of the theory of correspondence, it has been objected that Tarski's theory is systematically based on the assumption that "the frame theory, the axiomatic set theory is consistent, that is, it does not permit any contradiction, any formula of the form 'A and non-A' to be deduced according to the rules of inference of classical logic." Therefore, the "often so-called 'correspondence theory' of the W.[ahrheit] of Tarski's succession rests on a pure theory of coherence." Nevertheless, Tarski's influence cannot be denied:

"Like no other, this theory of truth has found wide resonance in recent philosophy and has inserted itself easily, almost by itself, into the philosophy of science as well as into metamathematics [...]. The Tarskian concept of truth is used today by all modern theories of truth."

Deflationary theories of truth

Redundancy theory

The redundancy theory of truth states that sentences in which the word "true" occurs are usually redundant. According to this theory, this term can be eliminated from language without loss of information; it is, in a sense, redundant. Frank Plumpton Ramsey, Alfred Jules Ayer, and Quine are usually cited as the main proponents of redundancy theory. According to Dummett, this approach can be traced back to Gottlob Frege, who formulated the basic idea of redundancy theory in his work Über Sinn und Bedeutung in 1892:

"You can just about say, 'The idea that 5 is a prime number is true.' But if one looks more closely, one notices that no more is actually said with this than in the simple sentence '5 is a prime number'. [...] From this it is to be gathered that the relation of the thought to the true may not, after all, be compared with that of the subject to the predicate."

Frege is already expressing here the central idea of redundancy theory, that the expression "true" basically contributes nothing to the meaning of the propositions in which it occurs, and is therefore redundant in content. In classic form, this idea is formulated in Ramsey's Facts and Propositions, where it is succinctly stated that "there is in fact no separate truth problem, but only a linguistic muddle [linguistic muddle]." Truth or falsity can primarily be attributed to propositions. If one says, "p is true", he thereby affirms only p, and if he says, "p is false", he thereby affirms non-p. But this would not change the content of the proposition. But this would not extend the content of the proposition p. Thus, for example, the proposition "It is true that Caesar was assassinated" means no more than the proposition "Caesar was assassinated". A sentence form such as "it is true" is used only for stylistic reasons, or to lend emphasis to one's own assertion.

Frege himself, however, rejects a theory of redundancy; for him truth is an indefinable logical basic concept and "Das Wahre" is an abstract object.

Against the redundancy theory it has been objected that the term "true" is not explained and not defined. Thus, against the Caesar example of Ramsey, a sentence can be constructed in which the term "true" occurs essentially and cannot be omitted for understanding: "Everything the Pope says is true."

Prosentential theory

Dorothy L. Grover, Joseph L. Camp Jr. and Nuel D. Belnap Jr. elaborated the prosentential theory of truth based on an idea by Franz Brentano.

Minimal Theory

Paul Horwich's minimal theory states that the property "true" is beyond any conceptual and scientific analysis.

Disquotation theory

The disquotation theory says: Truth is related to reality. The sentence "Snow is white" is true exactly when snow is white. No sentence is true by itself, reality makes it true.

Performative Theory

Ramsey's theory of redundancy had a major impact on the discussion of the concept of truth in linguistic analytic philosophy. One of the most important attempts at a critical elaboration was made by Peter Frederick Strawson in 1949 in his essay Truth, in which he developed a performative theory of truth. Strawson gives credence to the redundancy theory insofar as he claims that "one does not make a new statement when one says that a statement is true." Nevertheless, the mention of truth is not redundant, since "one is doing something beyond mere statement when one says that statement is true."

For Strawson, the expression "is true" is not a meta-linguistic predicate used to speak about sentences. Rather, it represents a "pointless utterance". The use of "is true" is a "linguistic consummation", with which one merely confirms a statement without saying anything new in terms of content. The expression "it is true that" is thus only the mode of utterance, a "performer which transforms an initially merely possible statement into a real (admittedly possibly false) assertion."

Coherence theory

The coherence theory of truth appeared at the end of the 19th century in the New Hegelianism of the Anglo-Saxon world, for instance in Francis Herbert Bradley and Brand Blanshard. It also played a role in the discussions of logical empiricism and the Vienna Circle, with Otto Neurath preferring a theory of coherence, while Moritz Schlick favoured a theory of correspondence. In its simplest form, the coherence theory states that the truth or correctness of a statement consists in being able to be fitted without contradiction into a system of statements. This is how Otto Neurath formulates it:

"Science as a system of statements is up for discussion in each case. [...] Every new statement is confronted with the totality of existing statements that have already been harmonized with each other. A statement is called correct if it can be integrated. What cannot be integrated is rejected as incorrect. Instead of rejecting the new statement, one can also, which is generally difficult to decide to do, modify the whole previous system of statements until the new statement can be integrated [...]."

Neurath's programmatic approach was elaborated into a comprehensive theory by Nicholas Rescher. However, Rescher explicitly uses the concept of coherence only as a criterion, but not to define truth. In defining "true," he subscribes to correspondence theory: Truth means the correspondence of a proposition with a fact.

Rescher distinguishes between two types of truth criteria: guaranteeing and authorizing. The former provide complete certainty as to the existence of truth, while the latter have only a supporting character. In Rescher's view, it is sufficient if such a criterion makes the existence of truth more probable. Rescher further restricts the validity of the concept of coherence to the explication of statements of fact - Rescher speaks of "data" - whereas, in his view, pragmatic criteria must be used for the truth of logical-mathematical statements. Data are thereby conceived from the outset as linguistic entities and not as pure facts. The acceptability of data is also justified according to pragmatic criteria.

According to Rescher, a theory or a system of statements can be called coherent if the following aspects are fulfilled:

- Comprehensiveness: All relevant propositions are considered; the theory is logically closed.

- Consistency: The theory does not contain any logical contradictory propositions.

- Cohesiveness: The propositions of the theory are explicated in their relations or contexts to the other propositions; the relations between the propositions are logically sound.

Pragmatism and intersubjectivity theories

The idea of intersubjectivity was already strongly elaborated in German Idealism. The connection to the problem of truth, however, was first recognized by Charles S. Peirce. Intersubjectivity is conceived by Peirce as the result of an unbounded community of researchers.

"On the other hand, all representatives of science are sustained by the joyful hope that the processes of research, if only pushed far enough, will yield a sure solution to any question to which they are applied. [...] They may at first obtain different results, but as each perfects its methods and processes, the results will be found to move steadily toward a predetermined center. [...] The opinion to which all researchers must fatefully agree in the end is what we mean by truth, and the object represented by that opinion is the real."

- Charles S. Peirce

While Peirce here suggests both intersubjectivity and correspondence with facts as aspects of truth, elsewhere he advocates principles of a pragmatic theory of truth:

"For truth is neither more nor less than that character of a proposition which consists in this, that belief in the proposition would, with sufficient experience and reflection, lead us to such conduct as would tend to satisfy the desires we should then have. To say that truth means more than this is to say that it has no meaning at all."

"For truth is neither more nor less than the character of a proposition, which consists in the fact that the conviction of it, given sufficient experience and reflection, would lead us to behave in a way that would aim at satisfying the desires we would then have. To say that truth means more than this is to say that it has no meaning at all."

- Charles S. Peirce

William James and John Dewey, the main representatives of the truth theory of pragmatism, referred to Peirce. According to them, the meaning of truth consists in the practical difference between true and untrue ideas. According to James, "there is an internal connection between the question of what truth is and the question of how we achieve truth." With regard to the verification process, it can be said:

"[T]he definition of truth is related to the criterion of truth."

For the truth criterion of usefulness in practice, a possible connection to the truth theories of Hegel and Marx was pointed out.

Bertrand Russell criticized this mixing of definition and criterion of truth. Determining whether the effects of a belief are good (in the long run) can be even more difficult than other forms of verification. Other people, moreover, might consider harmful those effects that we consider positive. "Intersubjective truth therefore presupposes that all individual interests are in harmony." For Herbert Keuth, the pragmatist theory of truth basically constitutes a theory of being true; also, in order to judge the success of a proposition, we cannot avoid verifying that it is consistent with the facts.

Based on the considerations of pragmatism and Wittgenstein's philosophy of language, the intersubjectivity theory of truth developed in the German-speaking world primarily as a theory of consensus (Jürgen Habermas, Karl-Otto Apel) and as a dialogical theory (Erlangen School).

Consensus theory of truth (Habermas)

For the consensus theory (also discourse theory), a statement is true if it deserves recognition by all reasonable interlocutors and a consensus - in principle unlimited - can be established about it. In his 1973 essay Truth Theories, Jürgen Habermas presented what is probably the most precise draft of such a theory to date. In it he defines "truth" as follows:

"Truth is what we call the validity claim that we associate with constitutive speech acts. A statement is true if the validity claim of the speech acts by which we, using propositions, assert that statement is justified."

- Jürgen Habermas

The bearer of truth is the statement, insofar as its content can be formulated in the standard form of the assertion of a fact (so-called constative speech act). If such a formulation is possible as a statement of fact, a claim to validity is made with the statement, which can be justified or unjustified. According to Habermas, a claim to validity is justified if it can be discursively redeemed.

Claims

Habermas distinguishes four types of validity claims that can neither be traced back to each other nor to a common foundation. Their fulfilment must be assumed by the speakers in communicative action. As long as communication succeeds, the mutual claims remain unthematized; if it fails, the assumptions must be examined to determine which of them remained unfulfilled. Depending on the claim to validity, different repair strategies exist:

- Comprehensibility: The speaker assumes understanding of the expressions used. In case of lack of understanding, the speaker is asked to explain.

- Truthfulness: The speakers assume each other's truthfulness. If this is doubted, the doubts can hardly be dispelled by the speaker suspected of untruthfulness himself.

- Truth: Truth is assumed with regard to the propositional content of speech acts. If this is doubted, a discourse must clarify whether the speaker's claim is justified.

- Correctness: The correctness of the norm asserted by the speech act must be recognised. This claim to validity is also only discursively redeemable.

Discourse

The claim to validity of the truth of a statement is redeemed in discourse. The redemption takes place in consensus, which, however, must not be an accidental consensus, but a justified consensus, so that "anyone else who could enter into a conversation with me would ascribe the same predicate to the same object". The precondition for such a justified consensus is an "ideal speech situation".

"The ideal speech situation is neither an empirical phenomenon nor a mere construct, but a reciprocally made assumption inevitable in discourses."

In order for an ideal speech situation not to remain mere fiction, four conditions of equal opportunity for all participants in the discourse must be met, first two trivial, then two non-trivial:

- Equality of opportunity with regard to the use of communicative speech acts, so that everyone can "open discourse at any time and continue it through speech and counter-speech, question and answer";

- Equality of opportunity with regard to the thematization and criticism of all previous opinions, so that "no previous opinion remains permanently withdrawn from thematization and criticism", and can therefore be problematized, justified or refuted ("postulate of equality of speech");

- Equality of opportunity with regard to the use of representative speech acts, so that it is possible for everyone to "express their attitudes, feelings and intentions", in order to guarantee the truthfulness of speakers towards themselves and others ("truthfulness postulate");

- Equality of opportunity with regard to the use of regulative speech acts, so that all have "the same chance [...] to command and to resist, to permit and to forbid, [...] etc.", so that "privileges in the sense of unilaterally obligatory norms of action and evaluation" are excluded.

To distinguish between truth and falsity according to consensus theory, it is important to identify reasonable consensuses:

"A reasonable consensus can be distinguished from a fallacious one in the last instance solely by reference to an ideal speech situation. [...] The conditions of empirical speech are [however] very often not identical with those of an ideal speech situation, even when we follow the declared intention to engage in discourse."

But in order not to have to abandon "the reasoned character of speech," we presuppose that a consensus reached is a reasonable consensus so long as "any consensus factually reached can also be questioned and scrutinized to determine whether it is a sufficient indicator of a reasoned consensus."

Dialogical Theory of Truth (Erlangen School)

The basis of the dialogical theory of truth (also dialogue theory) is the text Logische Propädeutik. Vorschule des vernünftigen Redens. In it, Wilhelm Kamlah and Paul Lorenzen develop the basic terms of the doctrine of reasonable speech, to which they also include the words "true" and "false". They emphasize the importance of "homology", i.e. the consensus of the participants in the conversation:

"Since in [...] judging the truth of statements we appeal to the judgment of others who speak the same language with us, we can call this procedure interpersonal verification. We establish in this way, by this 'method', agreement between the speaker and his interlocutors, an agreement which in Socratic dialogics was called 'homology'."

"True" and "false" are judgmental predictors for Kamlah and Lorenzen. What these terms mean can be reconstructed in natural language. On the basis of an essay by Lorenzen's student Kuno Lorenz, Jürgen Habermas explains the difference between consensus theory and dialogical theory of truth: defining the "truth conditions of a statement with the rules of use of the linguistic expressions occurring in this statement" means confusing intelligibility and truth. Because of this "analytic theory of truth", the Erlangen approach "does not contribute anything essential to the justification of a logic of discourse demanded by the consensus theory of truth [...]".

Truth in German Idealism

The representatives of German Idealism place the principle of subjectivity at the centre of their philosophy. For them, there is basically no objectivity located outside the subject. Truth, therefore, cannot be determined simply in terms of the theory of correspondence as the correspondence of a subject's judgment with an object located outside the subject.

The correspondence theory of truth is relevant to these idealist philosophers only for the aposterior truth of objects of experience. Without an external world existing independently of cognizing subjects, the question of truth has no great significance. Therefore, the primary interest of the German Idealists is the question of the "conditions of possibility" of truth.

Indicative of the changed status of truth is the position of Friedrich Schlegel:

"There is no true statement because the position of man is the uncertainty of floating. Truth is not found, but produced. It is relative."

Spruce

According to Johann Gottlieb Fichte, truth cannot be separated from the subject's experience of truth. Truth that is not experienced by a (general) subjectivity is a contradiction in terms. Nevertheless, a distinction must be made between the act of thinking and the content of thinking, and the claim to objective validity of truth must be maintained. A psychologistic-solipsistic position like Berkeley's is rejected by Fichte as "dogmatic idealism".

For Fichte, truth exists when there is a correspondence between that which the ego passively experiences or suffers and the active ego-performances. For Fichte, the object is identical with the passively and limitedly experienced processes of the subject. When these coincide with the subject's active processes, Fichte speaks of truth.

Nevertheless, truth is understood by Fichte as something supra-individual. There are not many, psychologistically understood truths, but only one indivisible truth. It does not depend on the individual will of the individual subjects, but on the general structures of a reasonable subject that is always already presupposed:

"[T]he essence of reason is one and the same in all rational beings. How others think, we do not know, and we cannot assume. How we ought to think, if we wish to think rationally, we can find; and so, as we ought to think, all rational beings ought to think. All inquiry must be from within, not from without. I ought not to think as others think; but as I ought to think, so, I should suppose, do others think. - To be in agreement with those who are not with themselves, would that be a worthy aim for a rational being?"

- Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Truth thus has an in-itself character: from the perspective of the individual subject, it apparently creates itself; transcendental, general subjectivity, on the other hand, knows about itself as the constitutional ground of unified truth. Absolute truth consists in complete self-identity and proves to be an infinite task for the finite I, an ideal that can ultimately never be achieved.

Hegel

For Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, the "ordinary" concept of truth, which conceives of it as the correspondence between judgment and reality, denotes a mere correctness. Hegel moves the concept of agreement from the level of the relation between thought and the thing to the level of thought and the thought grasping the thing. In this sense, truth is the agreement of an object with itself, that is, with its concept.

"Truth" is thus, for Hegel, an "immanent" process of "the thing itself". Hegel distinguishes in this context between the "ordinary" proposition and the "philosophical or speculative" proposition. The ordinary proposition takes the form of a judgment. It's components, subject and predicate, are first understood as separate from each other and as such are placed in a relation to each other. This is then true or false. In the positive-reasonable or speculative proposition, on the other hand, the dialectical movement of the thing itself is recorded.

The "concept" represents, in the Hegelian sense, the substantial constitution of all "things" (Sachen) and of the "whole". The concept of a thing principally and necessarily surpasses this thing itself, and this because of the finite moment of the thing. The absolute truth is God as spirit. He alone represents the absolute correspondence of concept and reality:

"God alone is the true correspondence of concept and reality; but all finite things have a falsity about them, they have a concept and an existence, but which is inadequate to their concept [...]."

For Hegel, the reason for a mismatch between concept and thing lies in the fact that things have an "untruth" in them. This is grounded in the fact that they are finite, whereas the concept grasping them is itself infinite. "Therefore they [finite things] must perish, whereby the inadequacy of their concept and existence is manifested. The animal as an individual has its concept in its genus, and the genus frees itself from the individual through death." According to Hegel, the "ontological constitution" of a finite thing consists, then, in the fact that it annuls itself; its being annihilated is the result of the dialectic which sets in because the being of finite things is not adequate to its own concept. The same is true of the "truth" of finite things: these "truths" are "finite truths" that must perish. In this they are not destroyed; this cannot happen to the spiritual, in contrast to the material; but together with the grasping of their development they form the result. Here truth shows itself in the proper sense - as the coming together, agreement (identity) of different things in a common medium. Hegel means it literally when he says:

"The truth of being as well as of nothingness is therefore the unity of both; this unity is becoming."

Objections to the concept of truth

See also: Münchhausen trilemma

Logical objections

From the assumption or the principle that there is a single truth, usually follows a concept of truth that implies an unconditional validity of what is called "true". Such a concept of truth thus implies at the same time a complete independence or separation of what is called "true" from what is judged (see dualism). Objections can be raised against such a rigid concept of truth.

The fundamental problem of all theories of truth is their circularity. The question arises in which sense they themselves are supposed to be true or right. A claim to truth in the sense defined by themselves would be arbitrary; a recourse to a norm preceding their definition would already presuppose the concept of truth, which had to be determined first.

Nietzsche and the consequences

Strong criticism first came from Friedrich Nietzsche, who pointed out the human interests, inclinations, will, and the instinctual that lies behind all knowledge. Subsequently, Wilhelm Dilthey developed a typology of metaphysicians, in which he tried to trace basic philosophical views to different psychological types.

Together with the strong historical consciousness and the increased knowledge of other peoples and cultures, at the end of the 19th century there was generally a phase of scepticism and doubt as to whether any truth is not generally dependent only on cultural views (see cultural relativism). The point here is not that laws of nature would be doubted, but rather the question of whether there cannot be many different points of view, and whether truths can be dependent on cultural developments, in other words, whether truths can be seen as constructions within a culture.

On the cognitivist level, Jakob Johann von Uexküll, for example, worked out the subjectivity of all perception by comparing the perceptual apparatuses of various animals and insects.

Postmodern

Postmodernist philosophers reject the idea of a single truth as a myth (Gilles Deleuze: "The concepts of importance, necessity, interest are a thousand times more decisive than the concept of truth. “).

Constructivism

Radical Constructivism (RC) claims to have solved the problem of truth by stepping out of this circularity. Since all perception is subjective, the view of the world or the view of things is also exclusively subjective. There are therefore only competing subjective truths. A comparison with the thing itself is not possible for systematic reasons. Ernst von Glasersfeld refers here, among other things, to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which states that one learns with one's mother tongue the truths contained and expressed in it. Different mother tongues thus also stand for different truths. The RK therefore consistently abandons the notion of one truth and thus of truth itself for systematic reasons.

Critical Rationalism

Critical rationalism holds to absolute truth as a regulative idea and points to the disastrous consequences of abandoning it. It explains differences in opinions in terms of their varying closeness to truth. Even though opinions are often errors and therefore false, they can still be more or less consistent with truth. Critical Rationalism resolves the supposed circularity of the concept of truth by abandoning reasoning oriented to justification in favor of criticism not aimed at justification. Critical Rationalism thus rejects the notion that there are criteria of truth. Truth is thus attainable, but it cannot be justified, proven, or made probable that it has been attained (fallibilism), and likewise, being true cannot be justified (epistemic skepticism). Nevertheless, it is possible through critical judgement (including perception) to make guesses, without arbitrariness, about which existing theory is closest to the truth for a given domain (negativism; checks and balances on guessing by guessing; 'checks and balances').

Aristotle formulated the basic principle of the correspondence theory

Search within the encyclopedia