Trinity

![]()

Trinity is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see Trinity (disambiguation).

The Trinity, Trinity or Trinity (Latin trinitas; ancient Greek τριάς trias 'threefold', 'trinity') is in Christian theology the unity of essence of God in three persons or hypostases, not three substances. These are called 'Father' (God the Father, God the Father or God the Father), 'Son' (Jesus Christ, Son of God or God the Son) and 'Holy Spirit' (Spirit of God). This expresses at the same time their distinction and their indissoluble unity.

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity was developed since Tertullian by various theologians, especially Basil the Great, and synods between 325 (First Council of Nicaea) and 675 (Synod of Toledo). The two main contrasting schools of thought were the one-hypostasis view and the three-hypostasis view. At the beginning of the Arian controversy in 318, the presbyter Arius from Alexandria held the view of the three hypostases God, Logos and Holy Spirit, Logos and Holy Spirit in subordination, the Logos Son was regarded by him as created as well as having a beginning and therefore not as true God. The bishops Alexander, who also came from Alexandria, and later Athanasius, in contrast, held the view of one hypostasis with God, Logos and Holy Spirit (with equal rank of Father and Son), so that Logos-Son or Christ counted at the same time as true God, who could redeem mankind by his work. Later it was also about the position of the Holy Spirit. After during the 4th century in the Christianity of the eastern part of the Roman Empire the three-hypostasis position temporarily dominated, in the western part however the one-hypostasis position, until the first Council of Constantinople or Council of Chalcedon a new compromise formula developed in the Creed with three hypostases of equal rank, God the Father, God the Son Jesus Christ as well as the Holy Spirit from the common divine essence. Today anti-Trinitarians and Unitarians are in the minority.

In the church year, Trinity Sunday, the first Sunday after Pentecost, is dedicated to the commemoration of the Trinity of God.

The idea of a divine trinity (triad) also exists in other religions, for example in ancient Egypt with Osiris, Isis and Horus. Hinduism also knows a trinity: the Trimurti, consisting of the gods Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. To what extent pre-Christian ancient concepts show analogies to the doctrine of the Trinity or even influenced its emergence is disputed. In Judaism and Islam, the concept of the Trinity is rejected.

Trinity in San Nicola (Giornico)

"Trinity icon" by Andrei Rublev (c. 1411).

Representation of the Trinity in the form of the mercy seat (epitaph from 1549)

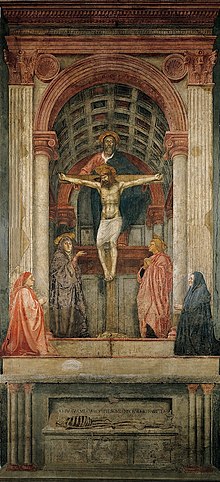

Masaccio: Trinity, fresco in the church of Santa Maria Novella

Biblical motifs

According to the Christian interpretation, the Old and New Testaments contain references to a doctrine of the Trinity, without, however, developing such a doctrine. In addition to formulas that were directly related to the Trinity, statements about the divinity of the Son and the Spirit are also significant for the history of reception.

Divine Trinity

Old Testament Motifs

New Testament talk of the Holy Spirit has antecedents in Old Testament formulations, for example, Gen 2:7 EU; Isa 32:15-20 EU; Ez 11:19 EU or 36:26 f. EU and contemporary theology, in which there are also certain parallels for ideas associated with Jesus Christ in the New Testament. References beyond this are later reinterpretations. For example, early Christian theologians generally refer to passages where the angel, word (davar), spirit (ruah) or wisdom (hokhmah) or presence (shekhinah) of God is spoken of, as well as passages where God speaks of himself in the plural (Gen 1:26 EU, Gen 11:7 EU) and especially the threefold "Holy!" of the seraphim in Isa 6:3 EU, which was included in the liturgy in the Trisagion. Again and again, the appearance of three men in Gen 18:1-3 EU was also referred to the Trinity. In the Jewish religion, however, the idea of the Trinity is rejected.

New Testament Motifs

One has diagnosed the specification of an "immanent will" of God already manifested in the Old Testament, as well as a speaking in "interchangeable" names of Spirit, Son and Father.

In any case, Paul coins the earliest formulations that are relevant for the history of the impact. In 2 Cor 13:13 EU he probably uses a blessing of the early Christian liturgy: "The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you!" In 1 Cor 12:3-6 EU, gifts of grace are attributed "in purposeful increase" to Spirit, Lord, and God. Eph 1:3-14 EU also orders Father, Son, and Spirit side by side and one upon the other.

Particularly influential in terms of impact history, though not the "prototype of Christian baptism," is the baptismal formula in Mt 28:19 EU. "In the name" (εἰς τὸ ὄνομα, literally "in the name") denotes a transfer. The narrative of the baptism of Christ in the Jordan by John the Baptist has been seen as a "counterpart" to this, because there the Father, Son, and Spirit are likewise united by the descent of the Spirit and the heavenly voice of the Father. Presumably this baptismal formula is an extension of a baptism "in the name of Christ." Also the Didache (the early "Catechism with instructions on liturgical practices"), written after 100 AD, already knows such an extended baptismal formula: "Baptize in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit".

Divinity of the Father

The term "God" in the New Testament mostly refers to the Father. God and the Son of God appear as distinct from each other, for example when it says: "God sent his Son" (John 3:17 EU). Or when Jesus "stands at the right hand of God" (Acts 7:56 EU). God, that is (e.g. in 1 Pet 1,3 EU) the "Father of our Lord Jesus Christ". This idea also concerns the future; in the end "the Son also will submit" and "God will be all in all" or "in all" (1 Cor 15:28 EU).

Divinity of Jesus Christ

Already the oldest texts of the New Testament show a close connection between God and Jesus: He works with divine authority - so much so that God himself in Jesus and through him carries out his creating, judging, redeeming and revealing himself. Among the texts that are particularly meaningful in Christological terms is the hymn in Col 1,15 EU ff., which, like Jn 1 EU, states among other things a pre-existence and a being created of the cosmos in Christ. The relation between Christ as Son of God and God the Father is important to several New Testament authors. A special intimacy is emphasized in the Abba-address and the "recognition" of the Father by the Son; especially the Gospel of John (Jn 17:21-23 EU) speaks of a relation of unity and mutual immanence between Father and Son in love.

Joh 20,28 EU is often interpreted to the effect that the disciple Thomas directly called Jesus "God". Thomas says there: "My Lord and my God! Jesus did not contradict the direct equation with God, unlike the Jews in Joh 5,18 EU: They understood the direct equation of God and Jesus and wanted to kill Jesus because of it.

Likewise, the designation "God" is applied to Jesus in some New Testament epistles, most clearly 1 John 5:20 EU in the phrase "true God." But also indirectly an equation of God and Jesus results, in that statements like "I am the Alpha and the Omega" appear in the mouth of God as well as in the mouth of Jesus (Rev 1,8 EU, Rev 22,13 EU).

Divinity of the Holy Spirit

According to Matthew and Luke the spirit is already active at the conception of Jesus. According to the evangelists the earthly Jesus is the carrier ("full") of the Holy Spirit, especially according to Paul the resurrected Jesus is the mediator. In John's Gospel the Spirit reveals the unity between Father and Son, even more, Jesus even confesses: "God is Spirit" (John 4:24 EU), with which the presence and work of God as Spirit becomes believable (John 15:26 EU; Acts 2:4 EU).

Development of the theology of the Trinity

Early Trinitarian Formulas

The biblical speech of Father, Son and Spirit can only set the course for the later receptions in the elaboration of a doctrine of the Trinity. Especially the ritual practice and prayer practice of the early Christians became formative.

The earliest clearly trinitarian-structured formulas are found as baptismal formulas and in baptismal creeds, which use three questions and answers to prepare and then carry out the transfer to Father, Son and Spirit.

Trinitarian formulas are also found in the celebration of the Eucharist: Through the Son, thanks are given to the Father, then the descent of the Spirit is requested. The final doxology glorifies the Father through the Son and with the Spirit (or: with the Son through the Spirit).

The regula fidei of Irenaeus, which was used among other things in the catechesis on baptism, also has a Trinitarian structure.

Theological development in the 2nd and 3rd century

Christian theology was not clearly defined in the first centuries, since according to the New Testament concept each Christian community was responsible for itself before God and no supra-congregational unions existed. So there were soon numerous disputes with the variants of Christology and Trinity, such as Adoptianism (the man Jesus was adopted by God via the Holy Spirit at baptism) or Docetism (Jesus was purely divine and appeared only as a man). Among various attempts to differentiate from Gnosticism and Manichaeism with their effects on Christianity were some - like modalistic monarchism (the Father and the Son are different forms of being of the one God in the 'oikonomic history of salvation', so that, exaggeratedly formulated, God himself died on the cross) - which were later condemned as heresy.

Justin

Justin Martyr uses numerous Trinitarian formulas.

Irenaeus

Irenaeus of Lyon develops - among others based on the prologue of the Gospel of John (1,1-18 ELB) - a Logos theology. Jesus Christ, the Son of God, is equated with the pre-existent Logos as the essential agent of creation and God's revelation. Irenaeus also elaborates an independent pneumatology. The Holy Spirit is God's wisdom. The Spirit and the Son do not come forth by emanation, which would place them on a different ontological level with the Father, but by "spiritual emanation."

Tatian

Tatian tries an independent special way, whereby the spirit also appears as a servant of Christ, the Logos, and is subordinated to a world-beyond-unchangeable God.

Athenagoras

The Greek word trias for God Father, Son and Holy Spirit, which is still the usual word for the Christian Trinity in the Eastern Churches, is first mentioned in the second half of the 2nd century by the apologist Athenagoras of Athens:

"They [Christians] know God and His Logos, know what is the unity of the Son with the Father, what is the communion of the Son with the Father, what is the Spirit, what is the unity of this triad, the Spirit, the Son, and the Father, and what is their distinction in unity."

Tertullian

In the Western Church, a few decades after Athenagoras of Athens had spoken of "trias", the corresponding Latin word trinitas was probably introduced by Tertullian, at least it is documented for the first time by him. It is a specially created neologism from trinus - threefold - to the abstract Trinitas - Trinity. A lawyer by training, he explained the essence of God in the language of Roman jurisprudence. He introduces the term personae (plural of persona - party in the legal sense) for Father, Son and Holy Spirit. For the totality of Father, Son and Holy Spirit he used the term substantia, which denotes the legal status in the community. According to his account, in the substantia God is one, but in the monarchia - the reign of the one God - three personae, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, are active. According to another version, Tertullian borrowed the metaphor "persona" from the theatre of Carthage, where actors held masks (personae) in front of their faces, depending on the role they were to play.

Theological development in the 4th to 7th century

Doctrines of the Trinity - Council of Nicaea (325)

The opposites in the Trinity conceptions from the late 2nd century on can be summarized under the currents of Monarchianism, Subordinatianism and Tritheism. Under the influential but sweeping fighting term Arianism, a variety of Subordinatianism appeared with Arius, which postulates the three hypostases God, Logos-Son, and Holy Spirit, but subordinates Logos and Holy Spirit to God, but denies true deity to the Logos-Son as created and with beginning-Jesus thus comes into a middle position between divine and human. This teaching was rejected by the first Council of Nicaea (325) as false doctrine. The hoped-for agreement failed to materialize. After the Council of Nicaea, a decades-long theologically and politically motivated dispute ensued between supporters and opponents of the Nicene Creed. The 'anti-Nicene' current gained many supporters in the years after Nicaea, especially among the higher clergy and the Hellenistically educated in the eastern part of the Roman Empire at court and in the imperial house, so that 360 the majority of bishops voluntarily or coercedly agreed to the new, 'Homoean' confessional compromise formula (see under Arian Controversy). Various 'anti-Nicene' synods convened, formulating various 'non-Nicene' Trinitarian confessions of faith between 340 and 360.

Pneumatology - Niceno-Constantinopolitanum (381)

In addition to the question of the Trinity, which had been in the foreground at the Council of Nicaea, the question of the status of the Holy Spirit was added in the middle of the 4th century. Is the Spirit of God a person of the divine Trinity, an impersonal power of God, another name for Jesus Christ or a creature?

The Macedonians (after one of their leaders, Patriarch Macedonios I of Constantinople) or Pneumatomachen (Spirit-fighters) held that the Son of God was begotten of God, thus also in consubstantiality with God, but that the Holy Spirit was created.

From 360 onwards the question was taken up by 'Old Nicetics' and 'Nine Nicetics'. Athanasius wrote his Four Letters to Serapion. The Tomus ad Antiochenos, written by Athanasius after the Regional Synod at Alexandria in 362, explicitly rejected the creatureliness of the Holy Spirit, as well as the essence-separateness of the Holy Spirit from Christ, and emphasized his belonging to the 'holy trinity'. Shortly afterwards came from Gregory of Nyssa a sermon on the Holy Spirit, and a few years later from his brother Basil the treatise On the Holy Spirit; his friend Gregory of Nazianzus delivered in 380 the Fifth Theological Discourse on the Holy Spirit as God. Almost simultaneously Didymus the Blind wrote a treatise on the Holy Spirit. The Greek theology of the fourth century uses the Greek word hypostasis (reality, essence, nature) instead of person, which is often preferred in theology even today, since the modern term person is often mistakenly equated with the ancient term persona.

Hilarius of Poitiers wrote in Latin about the Trinity and Ambrose of Milan published his treatise De Spiritu Sancto in 381.

In 381 the first Council of Constantinople was convened to settle the hypostasis dispute. There, the Niceno-Constantinopolitanum, related to the Nicene Creed, was adopted, which especially expanded the part concerning the Holy Spirit and thus emphasized the equal Trinity more than all previous confessions.

| […] We believe in the Holy Spirit, who is Lord and makes alive, who comes out of the father, who is worshipped and glorified with the Father and the Son, who has spoken through the prophets, […] |

The Niceno-Constantinopolitanum formulated the Trinitarian doctrine, which is still recognized today by the Western as well as by all Orthodox churches and was adopted in all Christological disputes of the next centuries.

Nestorianism

Nestorianism is the Christological doctrine that the divine and human natures are divided and unmixed in the person of Jesus Christ, and thus a form of the doctrine of two natures. It is named after Nestorius, who was Patriarch of Constantinople from 428 to 431 and was a major proponent of it. Mary is venerated in Nestorianism as the "Christ-bearer" but not as the God-bearer. The doctrine was condemned as heresy at the Council of Ephesus in 431. At the Council of Chalcedon in 451 it was rejected and the doctrine of two natures was adopted, according to which the divine and human natures of Christ are - according to the famous adverbs - unmixed and unchanged, undivided and unseparated.

Council of Chalcedon

At the Council of Chalcedon the Christological questions connected with the doctrine of the Trinity were specified.

Augustine

While both the Eastern and Western traditions of the Church have seen the Trinity as an integral part of their doctrine since the Council of Constantinople, there are nuances: the Eastern tradition, based on the theology of Athanasius and the Three Cappadocians, places somewhat more emphasis on the three hypostases; the Western tradition, based on Augustine of Hippo's interpretation of the Trinity a few decades later in three volumes, emphasizes rather the unity.

Augustine of Hippo argues that it is only through the Trinity that love can be an eternal trait of God. Love always needs a counterpart: a non-trinitarian God could therefore only love after he had created a counterpart whom he could love. The triune God, however, has from eternity the counterpart of love in himself, as Jesus describes it in Joh 17,24 ELB.

Filioque dispute

Different opinions about the relations between Father, Son and Spirit finally led to the Filioque controversy. The original Greek text, which the Council had established as dogma, reads: "... and to the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the Life-Giver, who proceeds from the Father ..." The Synod of Toledo in 447 approved the phrase, "... that the Spirit also is the Helper, not the Father Himself nor the Son, but proceeding from the Father and the Son. So unbegotten is the Father, begotten the Son, not begotten the Helper, rather proceeding from the Father and the Son." This formulation became accepted in the Roman Church from the 9th century onwards, but was not acceptable in the Orthodox Church, since it was a unilateral modification of the decision of a universally recognized ecumenical council, and since it contradicted the ancient interpretation of the Trinity.

The Filioque dispute was one of the main causes of the Oriental Schism (1054) and it has not been settled to this day.

Athanasian Creed

Then, in the 6th century, the Athanasian Creed, named after but not composed by Athanasius of Alexandria, emerged in the West. The theology of this creed is strongly based on the theology of the Western church fathers Ambrose († 397) and Augustine († 430) and was further developed by Bonaventure of Bagnoregio († 1274) as well as Nicolaus Cusanus († 1464).

| But this is the Catholic faith: We worship the one God in Trinity and Trinity in Unity, without confusion of persons and without separation of essence. Another is the person of the father, another the son's, another that of the Holy Spirit. But Father and Son and Holy Spirit have only one Godhead, equal glory, equal eternal majesty. […] Therefore, whoever wishes to be blessed must believe this of the Most Holy Trinity. |

Today most church historians regard the Niceno-Constantinopolitanum of 381 as the first and essential binding confession of the Trinity. The Athanasian Creed, which is about two hundred years younger and only widespread in the West, has never had the theological or liturgical significance of the Niceno-Constantinopolitanum, even in the Western Church.

Synod of Toledo (675)

The Catholic Church formulated the doctrine of the Trinity as dogma in the 11th Synod of Toledo in 675, confirmed it in the 4th Lateran Council in 1215, and never questioned it thereafter.

.jpg)

The Trinity in a French Bible of the 15th century

Schematic representation

Questions and Answers

Q: What does the Christian concept of the Trinity teach?

A: The Christian concept of the Trinity teaches that God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit are three distinct persons united in one divine nature who form one single being known as God.

Q: What is described as “the central dogma of Christian theology” with regard to Trinity?

A: The idea that God is composed of three distinct persons (God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit) united in one divine nature is described as “the central dogma of Christian theology” with regard to Trinity.

Q: What alternatives to Trinity were proposed prior to its acceptance by the First Council of Nicaea?

A: Prior to its acceptance by First Council at Nicaea, various other ideas were proposed to explain how there could be three persons claiming to be part of a single deity. These included Dyophysitism and Modalism.

Search within the encyclopedia