Trilobite

The trilobites (Trilobita, "three-lappers", from ancient Greek τρία tria "three" and λοβός lobós "lobes") are an extinct class of marine arthropods.

Trilobites existed during almost the entire span of the Paleozoic (Earth's Palaeolithic), from the 2nd series of the Cambrian (beginning 521 million years ago) to the mass extinction at the end of the Permian about 251 million years ago. Their exoskeletons (external skeletons), reinforced with calcite (calcium carbonate) to form a carapace, have been preserved as fossils in large numbers, making it possible to reconstruct the evolution and richness of form of the numerous species. This, in combination with their stratigraphic stability and wide geographic range, makes trilobites important guide fossils for the Palaeozoic, especially in the Cambrian.

Trilobites were among the first arthropods, an animal phylum with an exoskeleton, articulated body structure and many coordinated working legs. Their tracks have also been found many times as ichnofossils, these track fossils are called Rusophycus and Cruziana.

The extinct class Trilobita consists of nine recognized orders, over 150 families, over 5000 genera, and more than 15,000 described species. More species are found and described every year. Their diversity makes trilobites the most divergent group among all extinct creatures. The largest known trilobite with a length of more than 70 cm is Isotelus rex from the Upper Ordovician of North America.

Naming

The name "trilobite" was introduced in 1771 by Johann Ernst Immanuel Walch, but it was not until the beginning of the 19th century that the name became accepted in science.

Body type

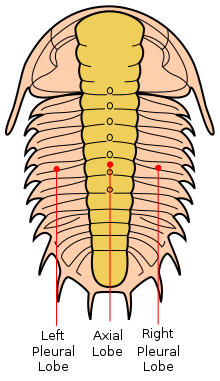

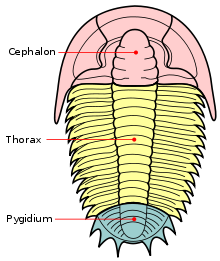

The trilobites ("Dreilapper", formerly also misleadingly called "Dreilappenkrebs") always consist of three sagittally running lobes ("lobes"), which give these animals their name: the spindle lobus and the two pleural lobes on the left and right side. The trilobites are also divided transversely into three limbs (tagmata): Head shield (cephalon), thorax and tail shield (pygidium).

Spindellobus

The middle lobus is called the spindle lobus or axis lobus. The piece of the spindle lobus on the head shield (cephalon) is called the frontal lobe (glabella) and often consists of several transversely running and often fused lobes. There are incomplete or completely dividing furrows between the lobes. The anterior part of the glabella is called the anteroglabella and the posterior part the posteroglabella. To the left and right of the posteroglabella are elevations called basal lobes in some species (for example, Agnostida).

The term spindle (or axis) is not unique. Sometimes this term is used to describe only the parts on the thorax, occasionally it is used to describe the parts on the thorax and tail shield (pygidium). The spindle is divided into several spindle rings (also called axial rings). The furrows between the rings are called spindle furrows (axial furrows).

The transverse lobus at the transition from the glabella to the rhachis is called the nuchal ring or occipital ring. It is pronounced in most species and sometimes bears a pointed process (tubercle), which is called occipital tubercle or nuchal nodule.

Rhachis comes from the Greek and actually means "spinal cord". The rhachis is the part of the spindle on the tail shield (pygidium) and is divided into different rhachis rings. The furrows between the rings are called rhachis furrows.

pleural lobe

The pleural lobes are the left and right sides of the trilobite. They pass from the tip of the cephalon laterally across the free cheeks, where compound eyes are often found, laterally across the thorax, and laterally to the tip of the pygidium. The pleural lobes are separated in some species by furrows on the cephalic and caudal shields. These furrows exist between the fringe and the tip of the spindle lobes. This fringing furrow is called the median preglabellar furrow on the head shield and the median postaxial furrow on the tail shield. In some species these furrows are fused and no longer visible.

Pleuron or pleure is the name given to the right and left parts of a segment (also splint) of the thorax. The ends of a pleuron may be rounded or pointed, depending on the species. Furrows on the pleurae are called pleural furrows.

Head shield (Cephalon)

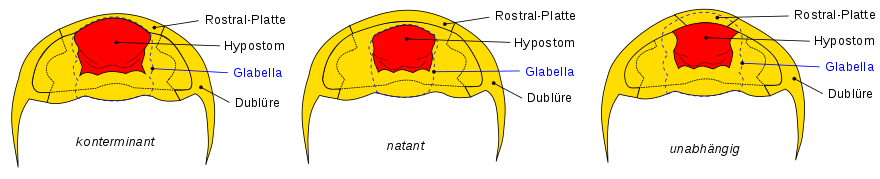

On the ventral side of the head shield, some species have a rostral plate, also called rostrum (lat. for "beak"). It can serve as an attachment for the hypostome. The hypostome is a plate on the underside of the cephalon in trilobites. It was probably part of the oral apparatus. The shape and positioning of the hypostome are essential features in the systematicclassification of trilobite species.

- Conterminant positioning: In the so-called conterminant positioning, the hypostome is attached to the rostral plate. The front of the glabella on the upper side is flush with the front of the hypostome.

- Natant positioning: In the so-called natant ("floating") positioning, the hypostome lies within the underside of the cephalon and therefore no longer has a connection to the rostral plate. Also in this positioning the glabella anterior side is flush with the hypostome anterior side.

- Independent positioning: The hypostome is attached to the duplicures, but is positioned independently of the glabella. The glabella is usually longer and thus overlaps the hypostome.

The trilobites possessed only one pair of specialized head appendages, these were formed as long limb antennae and presumably served as sensory organs. Only in the order Agnostida shorter, strongly bristled antennae appeared, which might have been more in the service of food intake (among other reasons, the inclusion of the Agnostida in the trilobites is doubted by quite a few researchers). The remaining limbs of the head segments, which were together covered by the head shield, correspond completely to the split legs of the trunk segments. It is therefore assumed that the legs of the trilobites, unspecialized, served both locomotion and feeding at the same time. Corresponding conditions are found in many crustaceans living today, for example in most leaf-footed crustaceans.

Facial Suture

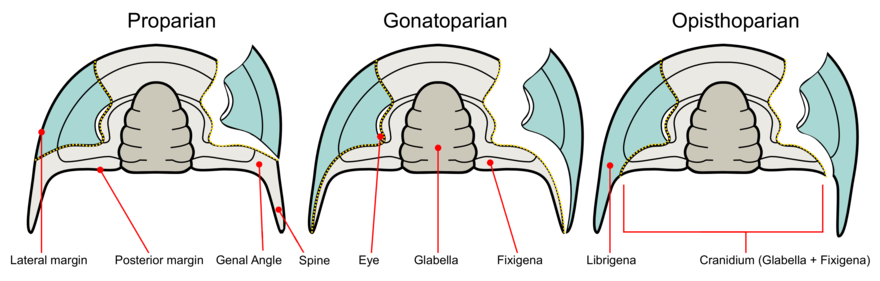

Explanation based on Lehmann, 2014

Another diagnostically important feature in the area of the cephalon is the facial suture (sutura facialis). The facial suture is a predetermined breaking point in the exoskeleton of the cephalon, which enables the trilobite to crawl out of the old carapace during moulting. The cephalic shield is divided into the cranidium, i.e. the glabella plus the fixigenae (sg. fixigena; fixed cheek or fixed cheek), and the two librigenae (sg. librigena; free cheek or free cheek). Depending on the position and course of the facial suture, several basic types are distinguished:

- Protoparous or hypoparous facial suture: In this case the skinning suture does not run over the cheeks, but along the entire length of the outer edge of the cephalon. During the moult only the double edge of the head shield is cut off (the part of the carapace that is bent towards the unarmoured ventral side). Free cheeks are not formed. This feature is especially common in primitive trilobites, e.g. within the order Agnostida (protopar), but also secondary in some highly specialized forms of the order Harpetida (hypopar).

- Propare facial suture: A facial suture is called propar, which runs along the outer edge of the cephalon only in the most anterior region and then passes over to the upper side of the cephalic shield, from there continues towards the eye mound (palpebral lobus) and along the inner side of the compound eyes to finally return to the outer edge of the cephalon before the cheek corner or the cheek spine.

- Gonatoparous facial suture: In the gonatoparous facial suture the basic course is similar. However, the flaying suture does not end at the outer edge of the head shield, but directly in the cheek corner or at the tip of the cheek spine.

- Opistoparous facial suture: An opistoparous facial suture differs from proparous and gonatoparous facial sutures in that the skinning suture ends after the cheek corner or cheek spine, i.e. not at the outer edge, but at the posterior edge of the head shield.

- Metaparous facial suture: A metaparous facial suture differs fundamentally from the other types. Here the skinning suture starts at the posterior edge of the head shield, runs towards the eye mound and back to an exit point also located at the posterior edge of the head shield.

Eyes

Not all trilobite species have developed eyes. If eyes are present, they are compound eyes, which consist of calcite like the exoskeleton. Thus, these eyes are not directly comparable to those of today's arthropods. However, most researchers assume that they are homologous to the compound eyes of the other arthropods. Since calcite is an inorganic material, the compound eyes have been very well preserved in fossilized exuviae and individuals because they have not been decomposed by microorganisms.

The eyes occur in three forms: Holochroal, schizochroal, or abathochroal compound eyes.

- In holochroal compound eyes, the individual eyes are closely spaced without a sclera in between. (Sclera is additional exoskeletal material that has a similar function as the sclera of the mammalian eye). The cornea covers all the individual eyes simultaneously. There are up to 15,000 individual eyes.

- In the schizochroal compound eyes, the single eyes are separated by a distinct thick sclera that grasps the eyes. Each individual eye has its own cornea, which is also bound by the sclera and extends deeper into the inner exoskeleton. There are only up to 700 individual eyes in this compound eye species.

- The abathochroal compound eyes also have a sclera. But this is much thinner than in the schizochroal compound eyes and at most just as thick as the single eyes. As in the schizochroal eyes, each single eye has its own cornea. But this ends already at the beginning of the sclera.

·

Holochroal compound eyes in Paralejurus

·

Schizochroal compound eyes in Erbenochile erbeni

Thorax

The thorax consists of segments. The number of segments and the shape is systematically relevant. Small trilobites of the Agnostida have only two or three segments. Larger trilobite species have up to 18. In animals with a special way of life, the segments can also take on different shapes. For example, they have spiny extensions, presumably to protect themselves from predators. On the other hand, they may be curved, as in the species of Paralejurus, to facilitate the presumably burrowing activity.

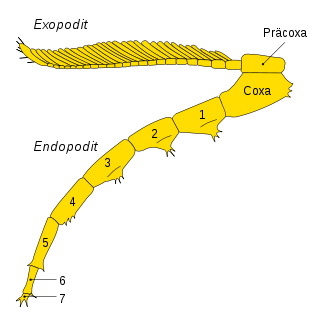

Split legs

Since only the upper side of the trilobites was hard-shelled and calcified, fossils that include the soft-shelled underside with the legs are very rare and have only been found in a few fossil deposits worldwide. Trilobites had what are called two-branched split legs. The first branch is called the swimming or gill leg (exopodite) and was used for swimming movement in the sea. The second branch is called the walking leg (endopodite) and was used for walking on the sea floor.

- The walking leg consisted of the coxa and seven other limbs. The coxa was attached to the precoxa. The limbs could have additional spines.

- The webbed leg was attached to the precoxa and consisted of two or more limbs, depending on the species. On the last limb or several of these limbs were fan-like extensions that allowed paddling in the water.

|

|

| |

| Subdivision of head shield into cranidium and free cheeks by facial suture and isolated free cheek of hydrocephalus as moult remnant | ||

Propare (left), gonatopare (middle) and opisthopare (right) facial suture in comparison

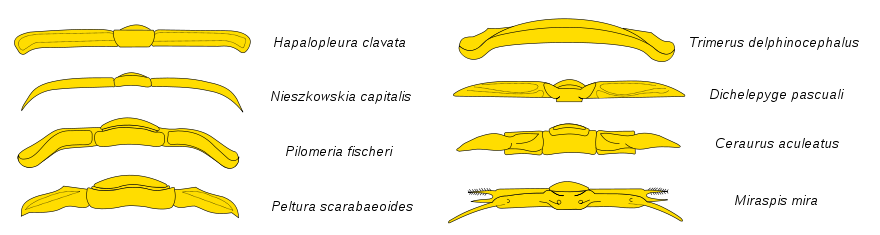

The rails of various species of trilobites

Schematic trilobite bone

Arrangements of the hypostome on the underside of the cephalon

Sagittal tripartite division into lobes or lobes

Transverse trisection

Questions and Answers

Q: What are trilobites?

A: Trilobites are extinct arthropods which were the first animals known to have eyes. They were very numerous during the early Palaeozoic era and their distribution was worldwide, but only in salt water environments.

Q: How did trilobites move around?

A: Trilobites had many lifestyles. Some moved over the sea floor as predators, scavengers, or filter feeders and some swam, feeding on plankton.

Q: What parts did trilobites have?

A: Trilobites had three main parts - a head (cephalon), thorax (chest) made of up to 30 segments, and a tail (pygidium). Underneath these parts were three pairs of legs for the head and paired legs for each pleural groove.

Q: When did trilobites appear?

A: Trilobites appeared some 600 million years ago during the Cambrian period.

Q: To what phylum do trilobite belong?

A: Trilobites probably belonged to the phylum Arthropoda which includes crabs, centipedes, spiders, shrimps and insects.

Q: How long did trilobite exist for?

A: Trilobite flourished as swimmers, crawlers and burrowers for some 350 million years before they disappeared in the Permian–Triassic extinction event.

Q: What is the largest size that a trilobite can reach? A: The world's largest trilobite was Isotelus rex which was found in 1998 by Canadian scientists on the shores of Hudson Bay and measured 72 centimetres (28 in). Most typically however they range from 1 millimetre (0.04 in) to 3-10 cm (1.2–3.9 in).

Search within the encyclopedia