Behaviorism

![]()

This article deals with a scientific-theoretical concept from the environment of behavioral and linguistic research. For the use of a similar term in political science, see behavioralism.

Behaviorism (derived from the American-English word behavior "behavior") is the name of the scientific-theoretical concept of investigating and explaining the behavior of humans and animals with scientific methods - i.e. without introspection or empathy. After important preliminary work by Edward Lee Thorndike, behaviorism was founded by John B. Watson at the beginning of the 20th century and was both popularized and radicalized in the 1950s, especially by Burrhus Frederic Skinner. Important pioneering work was also done by Ivan Petrovich Pavlov with his experiments on classical conditioning of behavior. Technoid social and cultural techniques were developed in behaviorism, but it offers not only classical or operant conditioning, but also a positively intended social utopia, such as that elaborated by Skinner in the novel Walden Two.

In the USA, the advocates of behaviorism were for decades the most influential behavioral researchers at the universities and decisive opponents of the psychoanalytic directions that were emerging at the same time. Comparative behavioural research, which had been emerging from animal psychology in Europe since the 1930s, was also unable to gain a foothold in the USA because of the dominance of behaviourism there.

The findings of behaviorist research are the basis for various behavioral therapy procedures, including the so-called systematic desensitization of patients with a phobia and the treatment of early childhood autism, but also the modern training of dogs and circus animals. Programmed learning, language laboratories, and today's popular PC programs for self-study of foreign languages are also a useful application of behaviorist theory.

Justification

The initial spark of behaviorism is John B. Watson's famous article "Psychology as the Behaviorist views it" (1913), in which he vehemently spoke out against the method of introspection that was common in psychology at the time. Watson's aim was to re-found psychology as a natural science, as it were. He relied exclusively on the so-called "objective method" by breaking down all behavior into stimulus and response; this form of behaviorism is therefore also called "molecular" behaviorism. Watson regarded as a stimulus any change in the external environment or inside the individual that is based on physiological processes, e.g. also a "lack of food", i.e. hunger; he regarded as a reaction any activity, be it turning towards or away from a light source or writing books. The form of behaviorism founded by Watson is also called "classical" or "methodological" behaviorism.

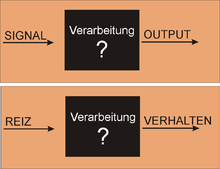

The physiological processes underlying observable behaviour are considered uninteresting by the behaviourist; from his point of view, they belong to the field of activity of physiologists. The behaviorist focuses exclusively on processes that take place between the organism and the environment. The organism itself is regarded by the classical behaviorist as a black box.

Skinner's main work Science and Human Behavior was published in the USA in 1953. In contrast to Watson and methodological behaviorism, Skinner's so-called "radical" behaviorism did not exclude inner-psychic processes in the study of behavior. However, statements about "mental" or "psychological" processes could never be made by outsiders, i.e. independent observers, but at best by the individual observing himself. If, for example, a student unintentionally responds to a teacher's question with a completely inappropriate answer, the student's "inner state" is often described as absent-minded. In reality, however, this attribution in no way explains the states inside the brain; in fact, it is merely an additional, figurative description for the student's erroneous utterance, i.e., for the student's reaction that is already known to the observer anyway.

The representatives of a behaviourist science of behaviour therefore demanded that all processes that affect an organism in an experiment (i.e. the causes of behaviour) should also be described in strictly scientific terms; psychology had to become an "exact science" in the sense of a natural science (whereby Skinner oriented himself more to the scientific concept of biology than to that of physics). One of the consequences of this was that non-scientific influences on behavior (for example, from "social structures" or from "culture and tradition") played no role in the behaviorists' studies unless they were defined at the level of environmental influences and behavior. Laboratory studies became the most important means of their research, since only there a very extensive control of all factors influencing the behaviour of test animals and test subjects is possible, and especially the Skinner box, which was developed especially for behaviourist experiments. Moreover, laboratory studies can be repeated much more easily than the field studies preferred by ethologists.

The research tradition that builds on Skinner's Radical Behaviorism as a philosophy of science is Experimental Behavior Analysis.

Hiding the interior

The renunciation of the use of inner-psychic processes for the explanation of behaviour, which cannot be described with scientific terms, has brought behaviourism persistent heavy criticism. It considers the brain to be a mere black box that automatically responds to a stimulus. However, the exclusive analysis of the connection between input and output ignores the fact that there are internal, variable, centrally nervous drives for behaviour, which become noticeable, for example, as sexual desire and as a feeling of hunger.

Skinner rejects the "black box" metaphor. Mentalistic statements like "He eats because he is hungry" are, according to him, no explanations for behavior. In Science and Human Behavior he writes: "He eats and he is hungry describe one and the same fact. (...) The habit of explaining one observation by another is dangerous in that it gives the impression that we have got to the root of the cause and therefore need look no further." Skinner rejects the notion of a Cartesian helmsman who, as it were, sits inside the head steering man; man as a whole individual ("organism as a whole") behaves in a certain way ("molar behaviorism") because of the environmental influences to which he has been subjected in his present and past environment, as well as because of the environmental influences to which his ancestors have been subjected in phylogenesis.

The Black Box Model

Questions and Answers

Q: What is behaviorism?

A: Behaviorism is an approach to studying behavior based only on what can be directly seen. It focuses on the relationships between stimuli and responses, and states that behavior can be studied without knowing what the physiology of an event is or using theories such as that of the mind.

Q: What did behaviorists believe about human behavior?

A: Behaviorists believed that all human behavior was learned through classical or operant conditioning, which is learning as a result of influences from past experiences. They denied the importance of inherited behaviors, instincts, or inherited tendencies to behave.

Q: Who were major contributors to the field of behaviorism?

A: Major contributors to the field of behaviorism include C. Lloyd Morgan, Ivan Pavlov, Edward Thorndike, John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner.

Q: What research did Pavlov conduct?

A: Pavlov researched classical conditioning through the use of dogs and their natural ability to salivate, produce water in their mouths.

Q: How did Thorndike and Watson view introspection?

A: Thorndike and Watson rejected looking at one's own conscious thoughts and feelings ("Introspection"). They wanted to restrict psychology to experimental methods.

Q: What type of research did Skinner focus on?

A: Skinner's research leant mainly on behavior shaping using positive reinforcement (rewards rather than punishments).

Q: How has modern evolutionary psychology challenged the blank slate premise?

A: The blank slate premise is opposed by modern evolutionary psychology which suggests that humans are born with mental experience or knowledge, rather than being born with a clean empty mind where everything must be learned after they grow up.

Search within the encyclopedia